Two weeks ago, we posted the first half of this post by Geof Huth, in which he discussed the history of court records in New York State and his role in inventorying the many early court documents held by the New York County Clerk in the Surrogate’s Courthouse. In this conclusion, he describes the documents found in the courthouse, the monumental move to the New York State Archives, and the importance of court records in understanding our history.

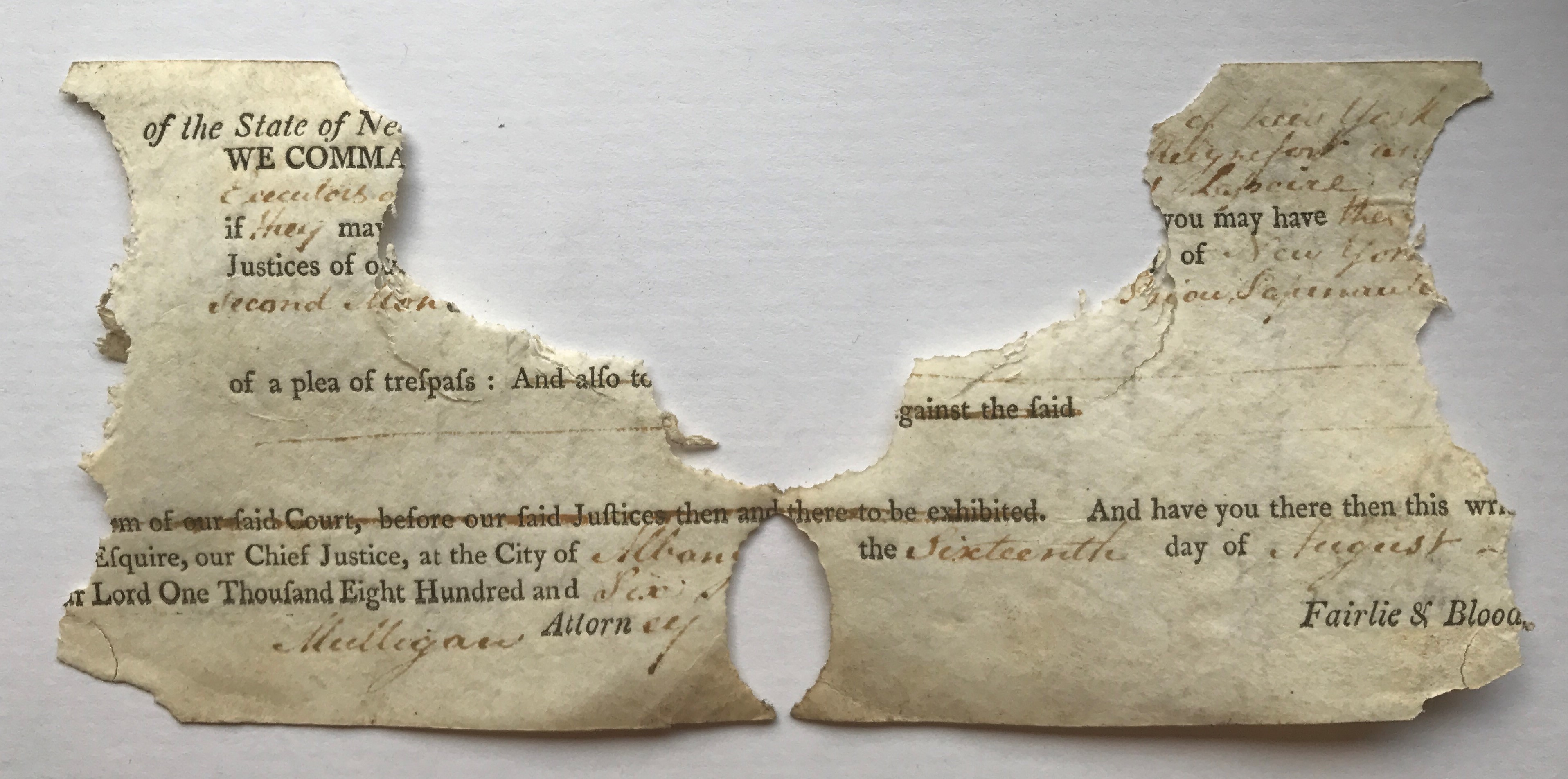

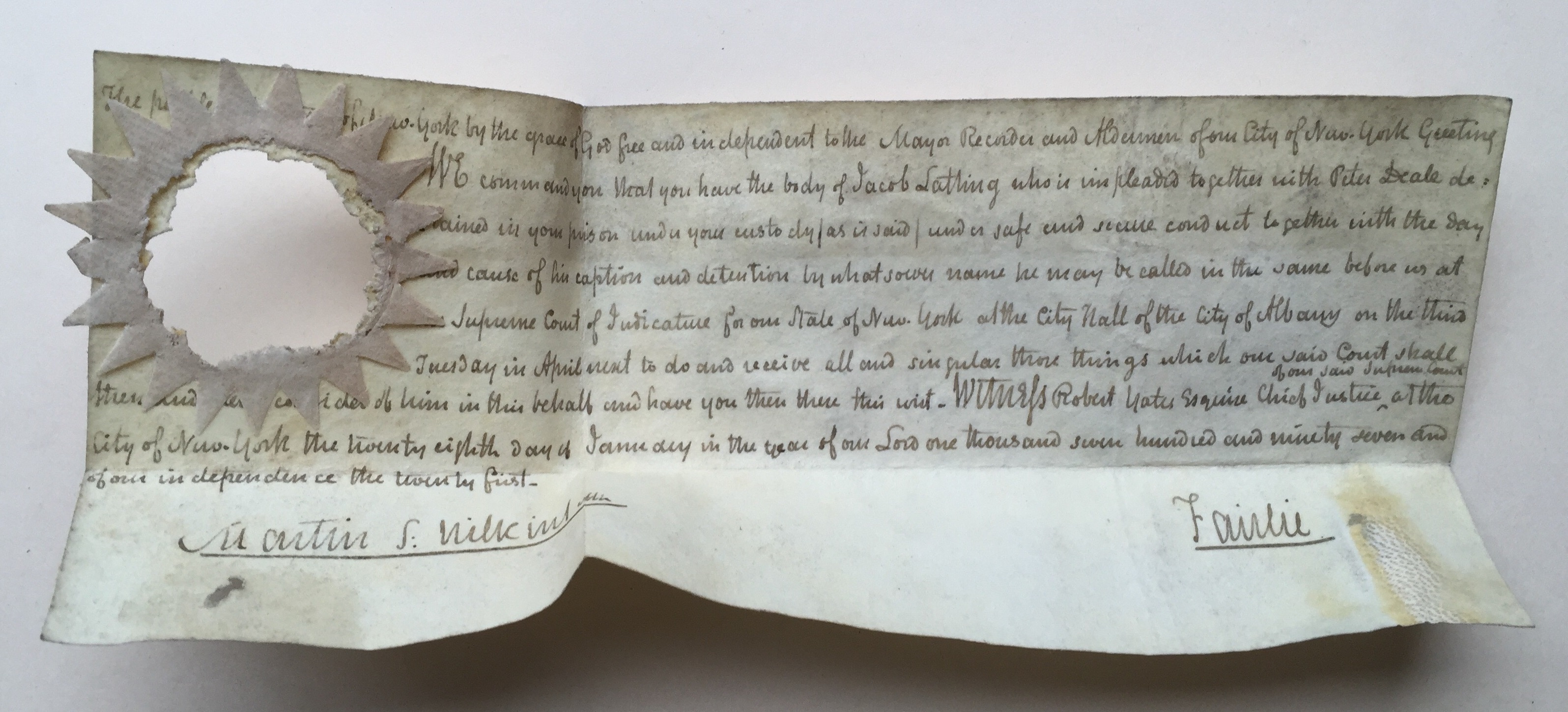

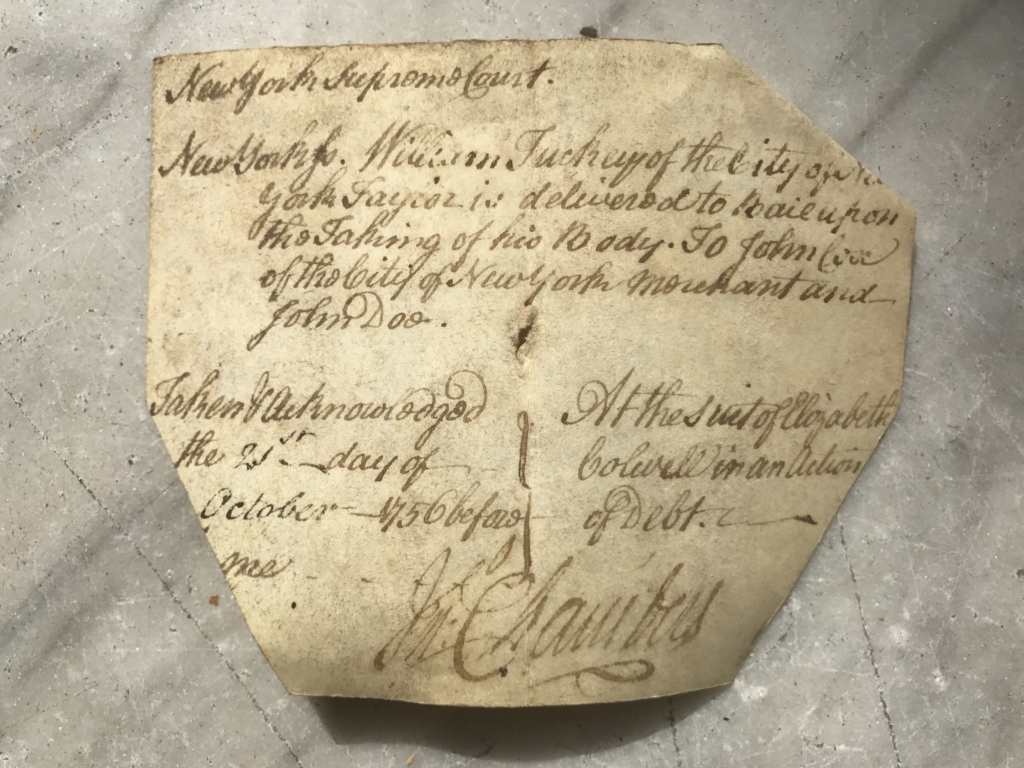

Photo: Supreme Court of Judicature Writ of Habeas Corpus, 1797

Then we worked. We took many hundreds of volumes and reviewed them one by one, bringing back together sets of volumes that had been separated likely for decades. We pulled many hundreds of Woodruff file drawers from their berths, vacuumed their contents of a century’s collection of dust, boxed them in order, and labeled the boxes. We sometimes spent a long time trying to determine exactly what certain records were and to bring order to boxes filled with a miscellany of sometimes fractured documents.

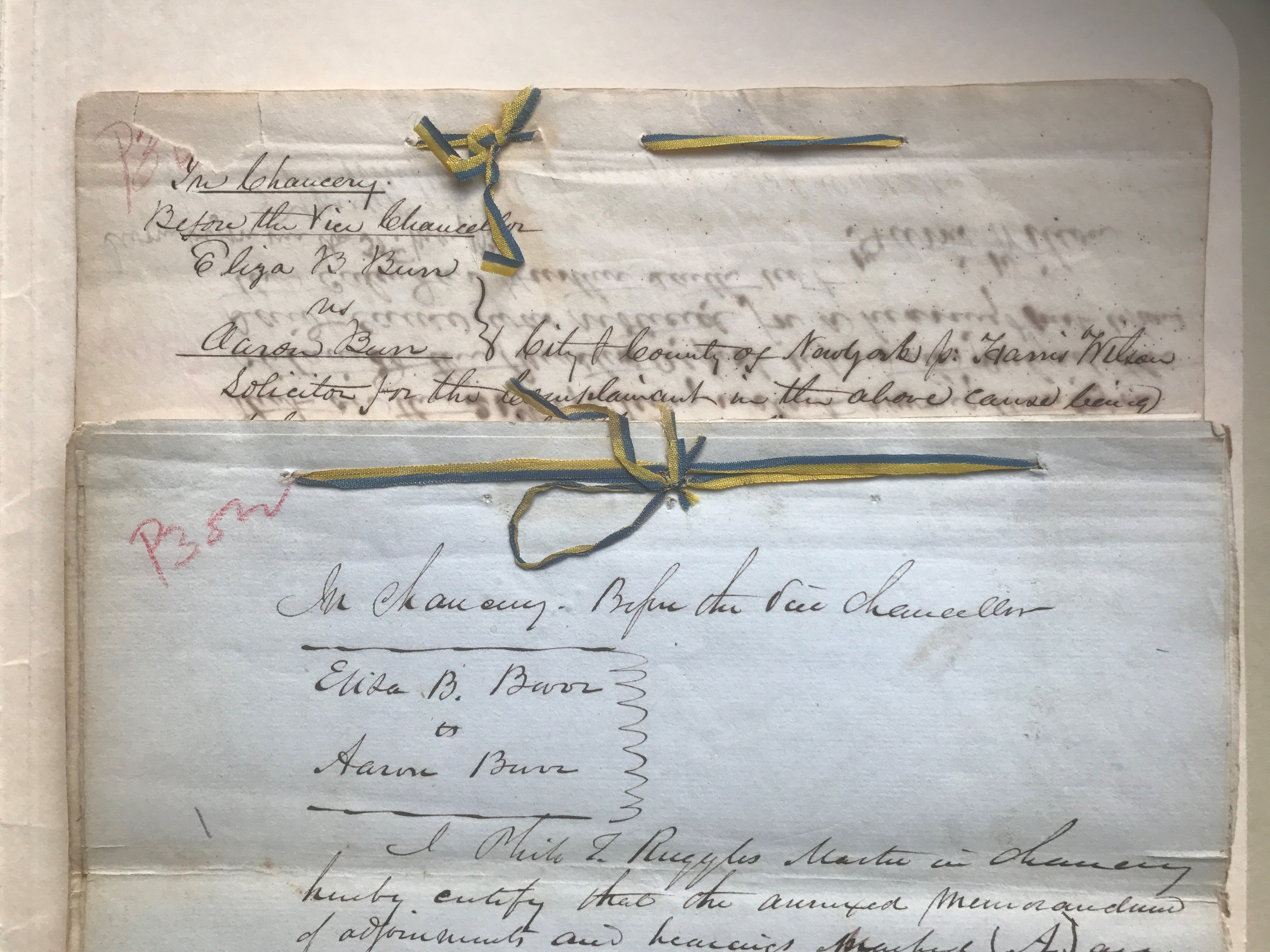

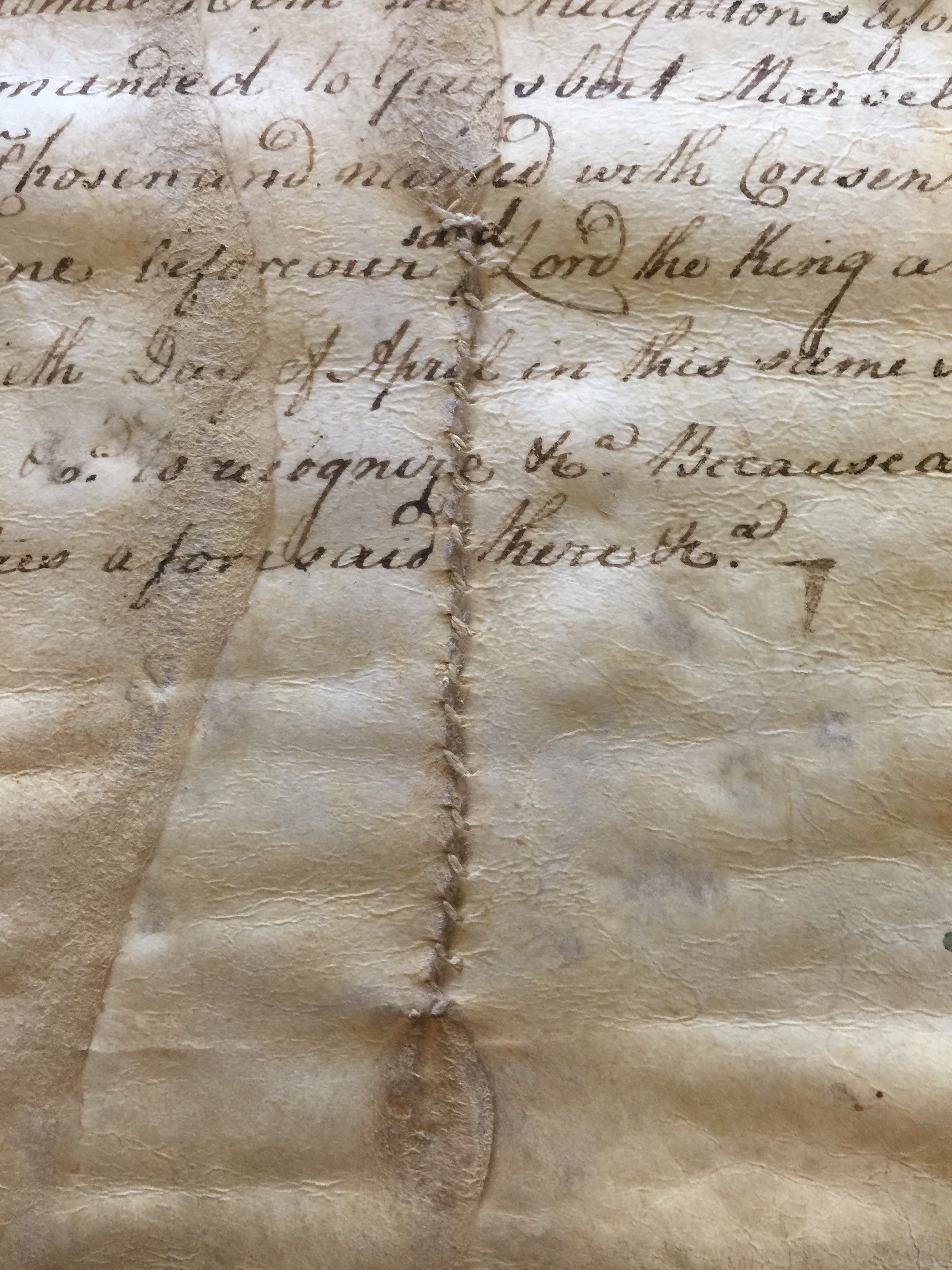

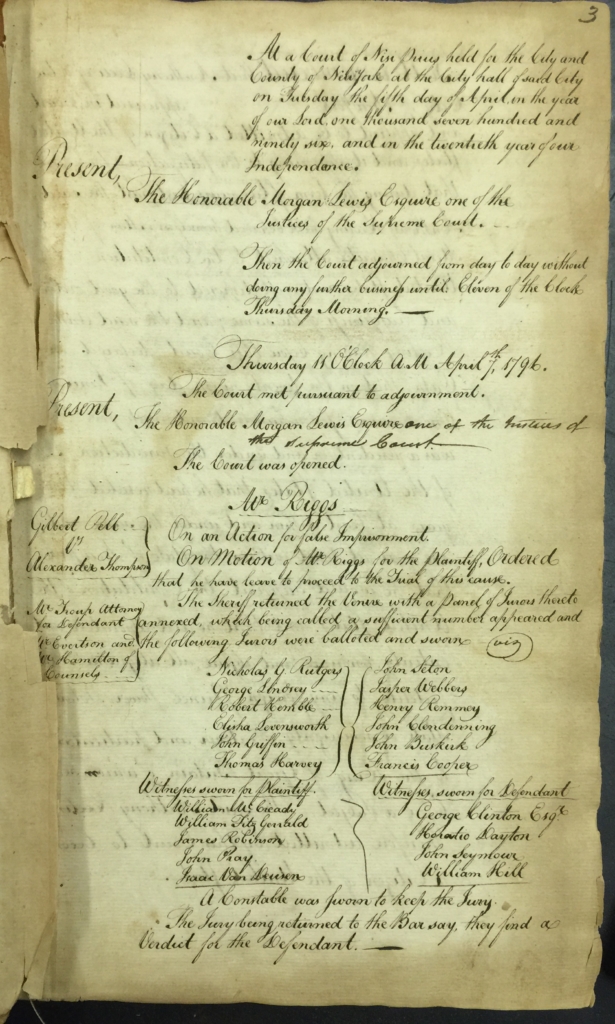

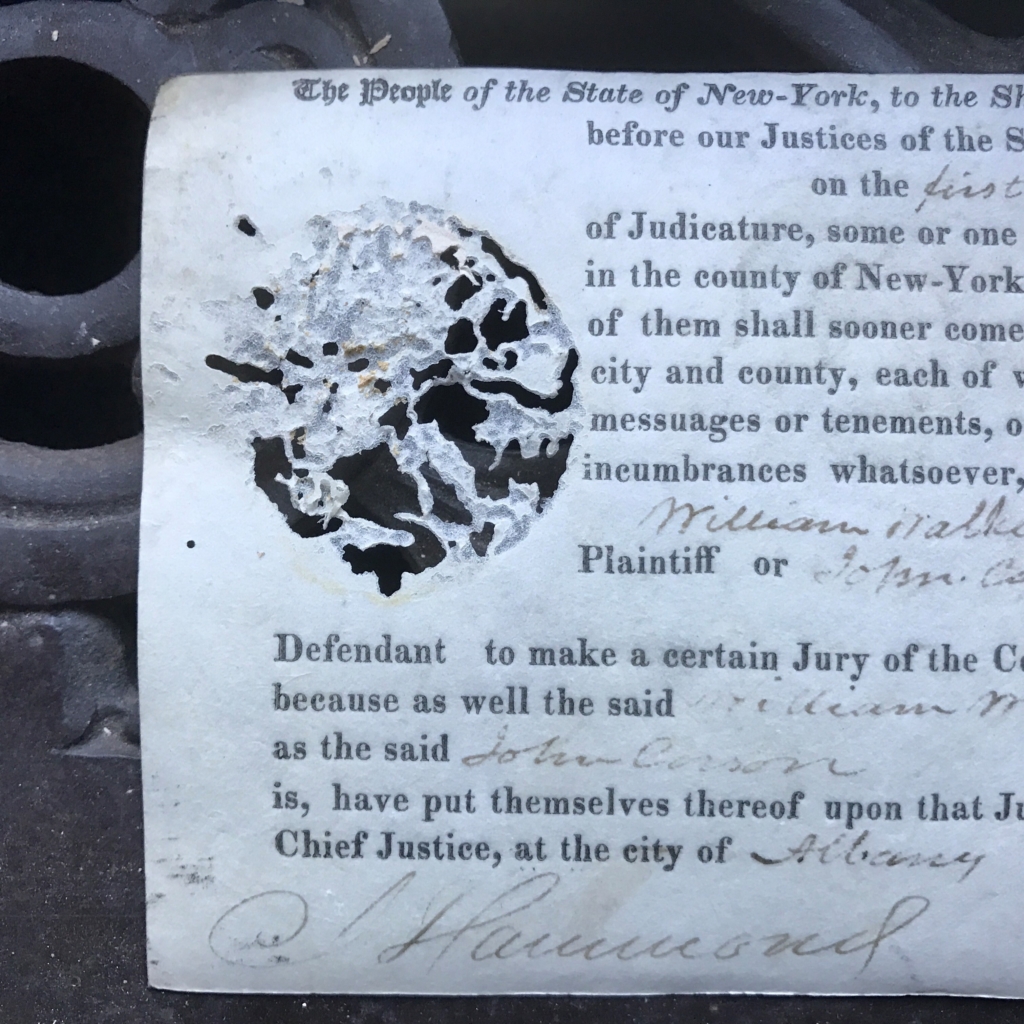

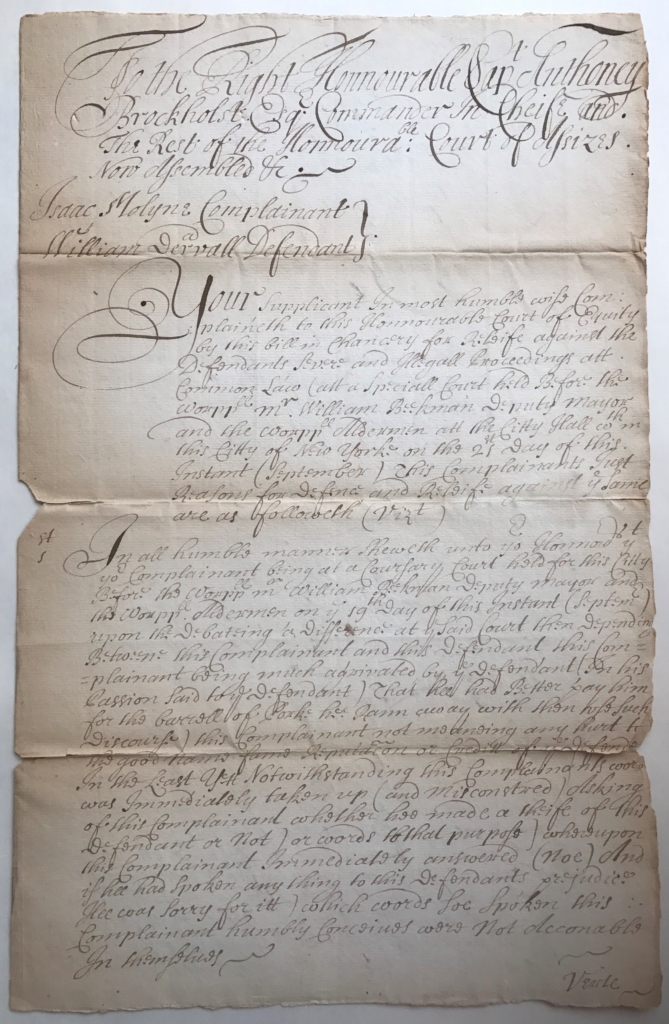

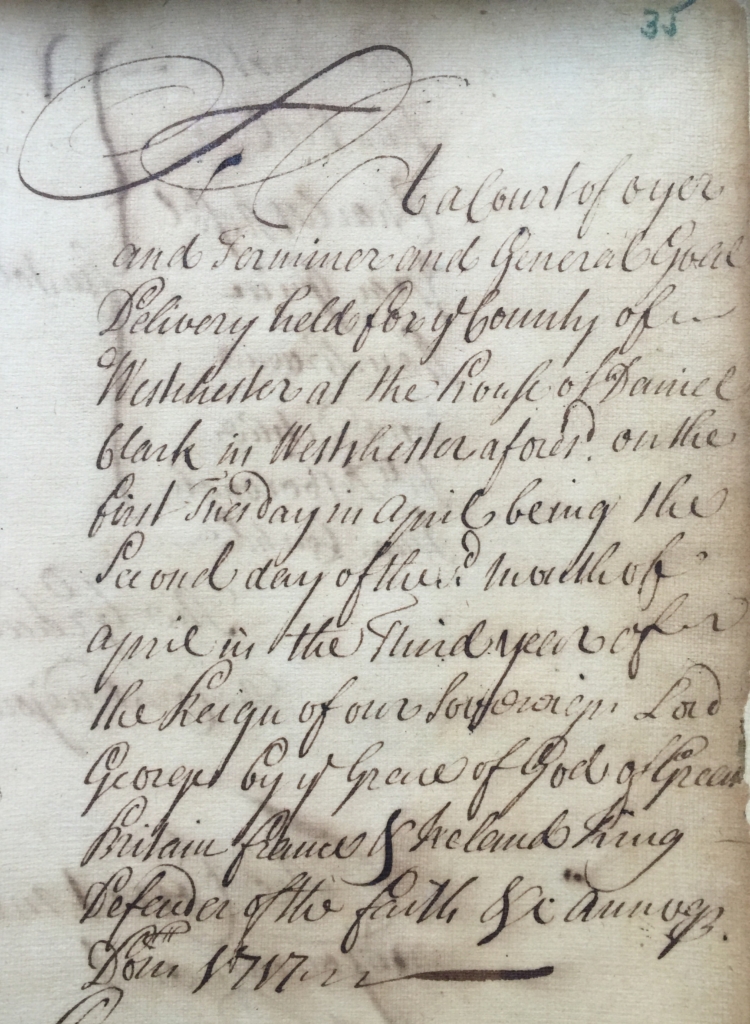

As we sorted through Woodruff file drawers, inventorying documents and recreating sets of volumes that had been divided many years before, we found amazing items: A twenty-five-foot roll of attorneys consisting of dozens of pieces of parchment stitched together. Literally hundreds of documents of Aaron Burr working as an attorney in civil practice—along with case papers relating to him as a litigant, and even the extensive paperwork relating to his divorce from his second wife, Eliza Jumel. Records documenting the seizure of Loyalists’ real property after the Revolution. Pleadings to the Supreme Court of Judicature in Alexander Hamilton’s own hand, and a large detailed accounting of all the debts owed to and of Nicholas Cruger, one of the two wealthy men of St. Croix who paid Hamilton’s expenses to attend King’s College (now Columbia University). Among the most interesting items were the many parchment writs with holes chewed through them by mice trying to eat the wheat paste sandwiched between the parchment itself and its paper seal.

Both the content and the visual aspect of these records captured our attention.

Even as we organized hundreds of thousands of records, describing each set of records—the minute books, the judgment books, the rule books, the writs of venire facias juratores, the writ books, the precipes, the records of wills proved—we still found pieces that caught our attention, that forced us to look a little harder, that encouraged us to read just a little further into them.

After six months, we had completed most of the inventory of records of the early courts with statewide jurisdiction, and we finalized an agreement for the New York State Archives to take ownership of these records. To part with such records may sound like a difficult decision to make, but it was an easy one. The State Archives already held the vast majority of the early records of other courts with jurisdiction across all of New York. State legislation has given the Archives the authority to take custody of such court records. Our own facility was no longer a feasible long-term storage venue for such records, and we did not have the staff to conserve the records or provide intensive reference services for users. We are the court system, and our core mission is the provision of justice. But the mission of the State Archives is to take care of, promote, and provide access to historical records of statewide significance, so they have the space, the facility, and the staff to do all the varied and needed archival work.

The last few months of this project focused on planning the transfer of these records. Usually, a records transfer is relatively easy. Someone picks up a number of cubic-foot boxes and moves them elsewhere. This time, the project was much more complex. First, the quantity was much larger than most transfers. Second, there were about 2,000 individual items to move (boxes in various sizes, large portfolios, and extra-large volumes that did not fit in boxes), and the combined weight of the records was probably four to five tons. In addition, some documents were fragile and required special care during transport. One particularly challenging set of records was the large portfolios, which were 38 inches in length, 12 inches wide, and bulging in the centers and protruding from all four sides as the variously sized parchments were centered within the two boards of each portfolio.

The State Archives team, headed by Maria Holden, Director of Archival Services, did a masterful job of conceptualizing and implementing this complex move. They used the detailed data we had collected on the records (in a database and a 550-page inventory) to create solutions that addressed the unique problems of transferring these records. Jim Folts, the State Archives’ Head of Researcher Services and an expert on early New York State court records, joined Maria on site prior to the move to make plans. The move itself was so complex and the quantities so large that the work took three four-day weeks. In the first days of each week, Archives staff taped each box shut with gentle tamper-evident tape, confirmed the contents of each, barcoded each, and staged the records for pickup. On the last day, movers pulled the boxes as Archives staff supervised and scanned each barcoded item as it left the building. The records were so heavy that no truck could be filled to its capacity by volume, and five truckloads were needed to move all the records. Yet, in the end, the move worked almost flawlessly.

Now the records are stored on the eleventh floor of the Cultural Education Center in Albany, in a storage area with high security and perfect environmental controls, which do much to help preserve the records. The Archives has a staff of conservators to repair and stabilize the records, as well as a team of archivists familiar with early court records and ready to help users—historians, everyday people, and any other researchers. Because of the preparatory work we in the Unified Court System accomplished, these records were organized, described, and ready for use when they arrived at the State Archives. Now, a little more of the history of New York is ready to meet its potential.

And why are these records important? Certainly, they tell the stories of individuals and their very human conflicts. Some lucky genealogists will discover unexpected details about their ancestors’ lives because of these records. But these records tell bigger stories. They tell the story of how New York’s system of jurisprudence has changed over time, and how it also has stayed so much the same: how phrases that appeared in court documents three centuries ago appear in them today. They tell the story of the struggle humanity continues to make towards a more just society, including New York’s own history abolishing slavery and recognizing the essential humanity of all people. These records also tell the story of a different society at a different time. Because of the multitudinous details within these records, we can construct in our imagination a reasonable approximation of what life was like at that time: how people argued, what they thought was right and wrong, and even how they made a nation out of a string of colonies along the eastern coast of a wide continent.

The human mind can remember only as long as the heart of its body keeps beating—and sometimes not even that long. To remember the past, we cannot count on ourselves. We have to depend on records, and sometimes these records seem to provide nothing but a static accounting of a life of conflicts large and small—but in the end, in a deep enough body of records, these numerous stories cohere to form a matrix of information so rich that we can peer back through all of it to see the clear outlines of the past. The view may be gauzy and some of our conclusions may be a little askew, but through the lens that records provide us we can see what we never ourselves experienced. And with the wisdom that comes from understanding the failures and successes of the past, maybe, we can make this world, this transient time we are living in, a little bit better for everyone.

Comments · 1

Comments are closed.