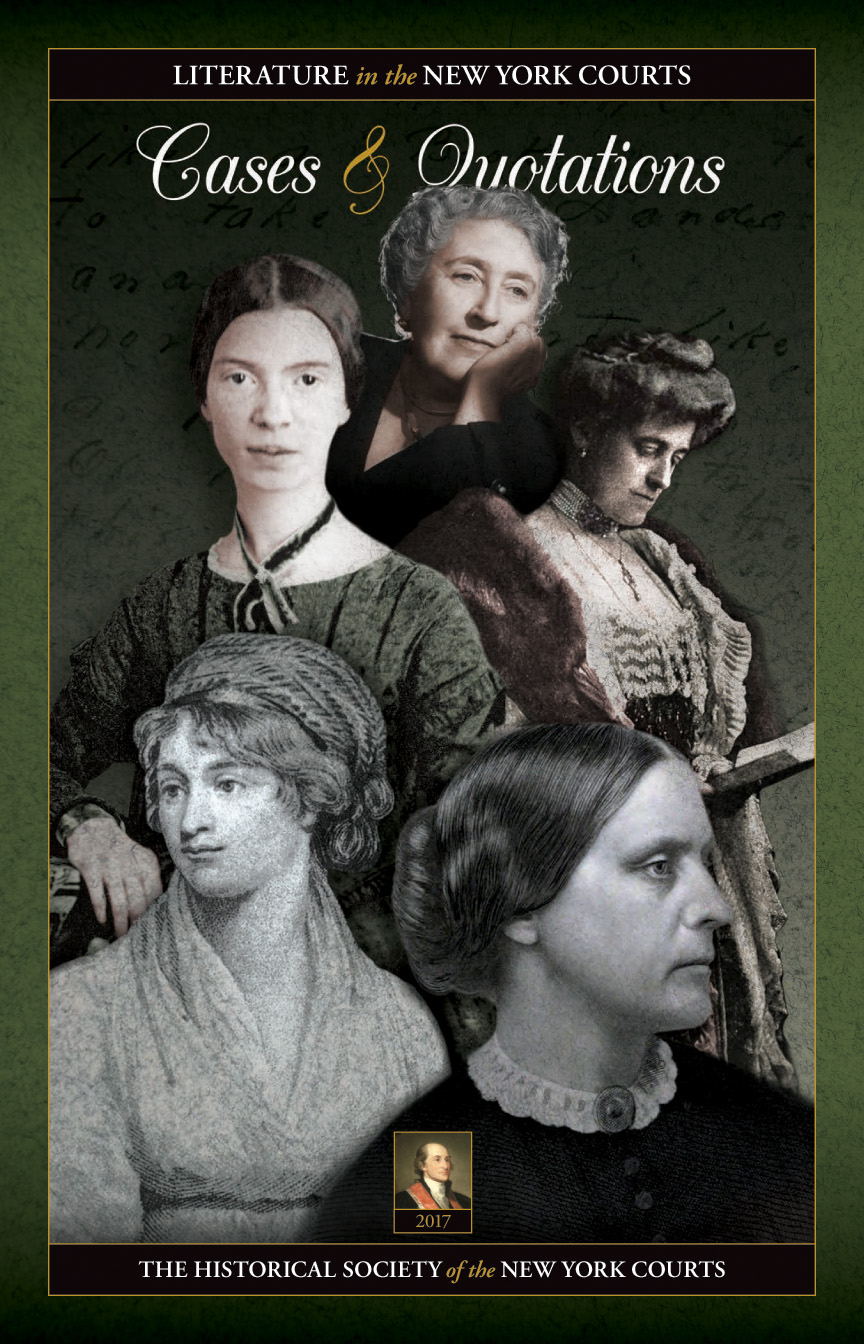

Description

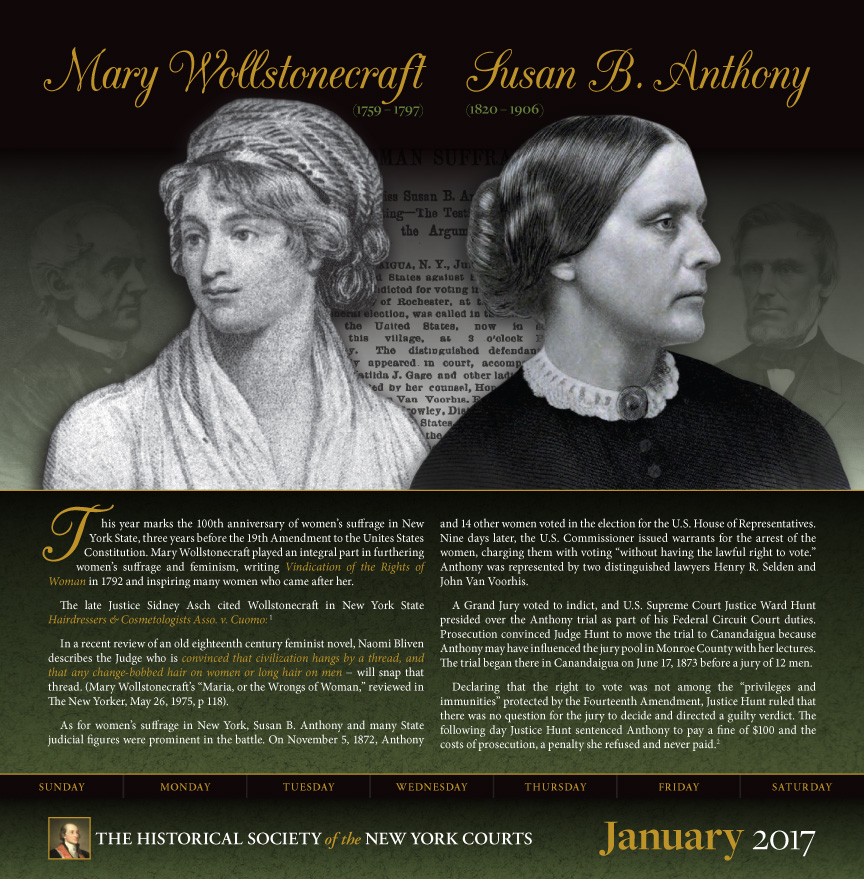

Mary Wollstonecraft (1759 – 1797) and Susan B. Anthony (1820 – 1906)

Amendment to the Unites States Constitution. Mary Wollstonecraft played an integral part in furthering

women’s

suffrage and feminism, writing Vindication of the Rights of Woman in 1792 and inspiring many women

who

came after her.The late Justice Sidney Asch cited Wollstonecraft in New York State Hairdressers & Cosmetologists

Asso.

v. Cuomo:1

In a recent review of an old eighteenth century feminist novel, Naomi Bliven describes the Judge who is convinced

that civilization hangs by a thread, and that any change-bobbed hair on women or long hair on men −

will

snap that thread. (Mary Wollstonecraft’s “Maria, or the Wrongs of Woman,” reviewed in The New

Yorker,

May 26, 1975, p 118).

As for women’s suffrage in New York, Susan B. Anthony and many State judicial figures were prominent in the

battle. On November 5, 1872, Anthony and 14 other women voted in the election for the U.S. House of

Representatives. Nine days later, the U.S. Commissioner issued warrants for the arrest of the women,

charging

them with voting “without having the lawful right to vote.” Anthony was represented by two distinguished

lawyers Henry R. Selden and John Van Voorhis.

A Grand Jury voted to indict, and U.S. Supreme Court Justice Ward Hunt presided over the Anthony trial as

part

of his Federal Circuit Court duties. Prosecution convinced Judge Hunt to move the trial to Canandaigua

because

Anthony may have influenced the jury pool in Monroe County with her lectures. The trial began there in

Canandaigua on June 17, 1873 before a jury of 12 men.

Declaring that the right to vote was not among the “privileges and immunities” protected by the Fourteenth

Amendment, Justice Hunt ruled that there was no question for the jury to decide and directed a guilty

verdict.

The following day Justice Hunt sentenced Anthony to pay a fine of $100 and the costs of prosecution, a

penalty

she refused and never paid.2

Images:

Engraving portrait of Ward Hunt by Max Rosenthal. The New York Times, June 18, 1873. Copyright The New

York

Times

Carte de visite of Mary Wollstonecraft after stipple engraving by James Heath. Library of Congress,

Prints

& Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-64309

The New York Times, June 18, 1873. Copyright The New York Times

Portrait of Susan B. Anthony. Published in History of Woman Suffrage, eds. Elizabeth Cady Stanton,

Susan B.

Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage

Portrait of Henry Rogers Selden. Courtesy of the Court of Appeals

Footnotes:

1. 83 Misc. 2d 154, 165 (N.Y. Sup. Ct. 1975)

2. See generally, Rosenblatt, Albert M. “Selden, Henry R.; Van Voorhis, John; Hunt, Ward.” The Judges

of

the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History (2007), 84-92; 620-636; 100-107; also,

Gordon, Ann D. The Trial of Susan B. Anthony, Federal Judicial History Office (2005)”>

February 2017

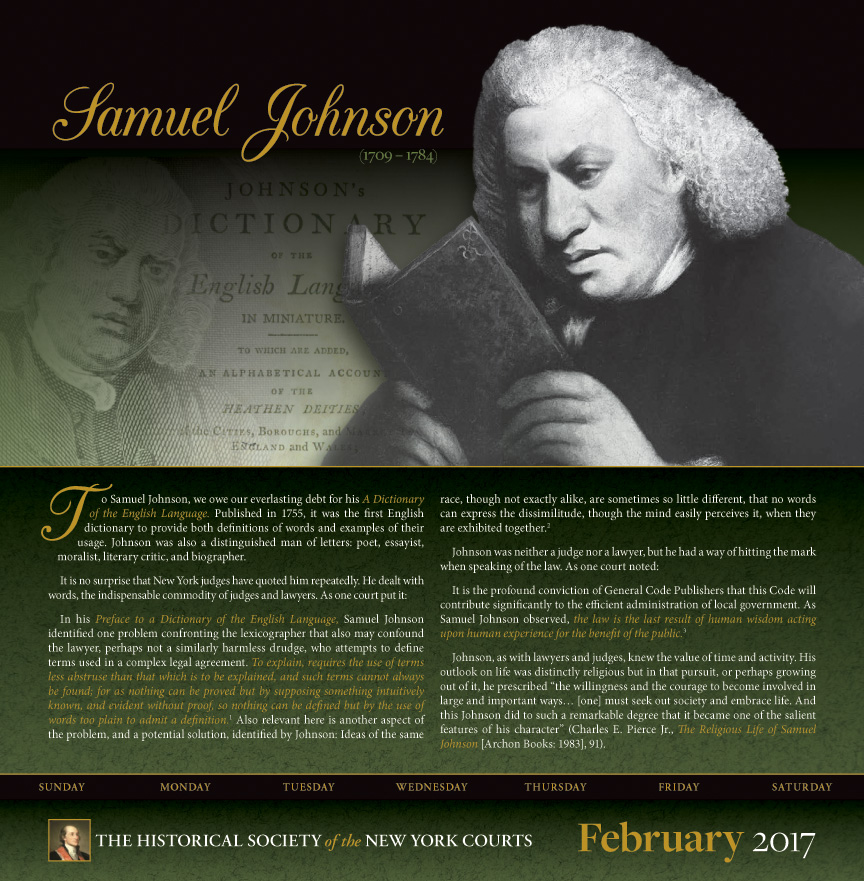

Samuel Johnson (1709 – 1784)

To Samuel Johnson, we owe our everlasting debt for his A Dictionary of the English Language. Published in 1755, it was the first English dictionary to provide both definitions of words and examples of their usage. Johnson was also a distinguished man of letters: poet, essayist, moralist, literary critic, and biographer.

It is no surprise that New York judges have quoted him repeatedly. He dealt with words, the indispensable commodity of judges and lawyers. As one court put it:

In his Preface to a Dictionary of the English Language, Samuel Johnson identified one problem confronting the lexicographer that also may confound the lawyer, perhaps not a similarly harmless drudge, who attempts to define terms used in a complex legal agreement. To explain, requires the use of terms less abstruse than that which is to be explained, and such terms cannot always be found; for as nothing can be proved but by supposing something intuitively known, and evident without proof, so nothing can be defined but by the use of words too plain to admit a definition.1 Also relevant here is another aspect of the problem, and a potential solution, identified by Johnson: Ideas of the same race, though not exactly alike, are sometimes so little different, that no words can express the dissimilitude, though the mind easily perceives it, when they are exhibited together.2

Johnson was neither a judge nor a lawyer, but he had a way of hitting the mark when speaking of the law. As one court noted:

It is the profound conviction of General Code Publishers that this Code will contribute significantly to the efficient administration of local government. As Samuel Johnson observed, the law is the last result of human wisdom acting upon human experience for the benefit of the public.3

Johnson, as with lawyers and judges, knew the value of time and activity. His outlook on life was distinctly religious but in that pursuit, or perhaps growing out of it, he prescribed “the willingness and the courage to become involved in large and important ways… [one] must seek out society and embrace life. And this Johnson did to such a remarkable degree that it became one of the salient features of his character” (see: Pierce, Jr., Charles E. The Religious Life of Samuel Johnson (Archon Books: 1983), 91.)

Images:

Endpapers of Johnson’s Dictionary of the English Language in Miniature. Courtesy of D’Youville College Archives, Buffalo, NY

Dry plate negative portrait of Samuel Johnson after painting by Sir Joshua Reynolds. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-det-4a26286

Footnotes:

1. Johnson, Samuel. A Dictionary of the English Language: An Anthology at 29. Edited by David Crystal, 2005, 29-30

2. Innophos, Inc. v. Rhodia, S.A., 38 A.D.3d 368 (1st Dept. 2007)

3. Woodfield Equities, L.L.C. v. Inc. Vill. of Patchogue, 357 F. Supp. 2d 622 (E.D.N.Y. 2005)

March 2017

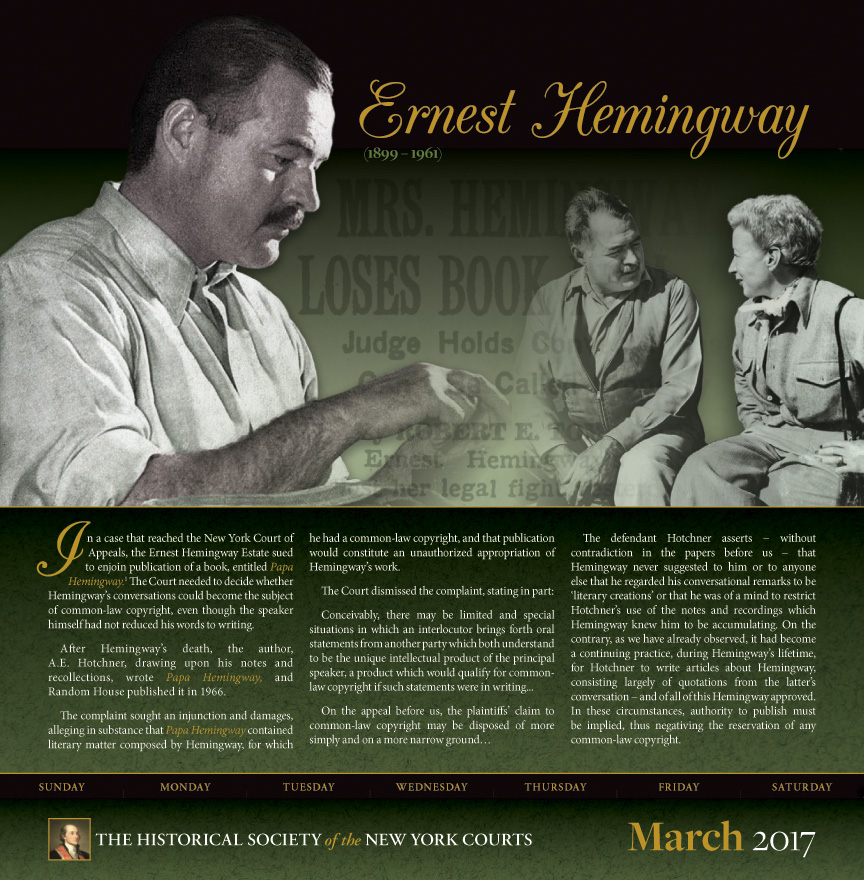

Ernest Hemingway (1899 – 1961)

In a case that reached the New York Court of Appeals, the Ernest Hemingway Estate sued to enjoin publication of a book, entitled Papa Hemingway.1 The Court needed to decide whether Hemingway’s conversations could become the subject of common-law copyright, even though the speaker himself had not reduced his words to writing.

After Hemingway’s death, the author, A.E. Hotchner, drawing upon his notes and recollections, wrote Papa Hemingway, and Random House published it in 1966.

The complaint sought an injunction and damages, alleging in substance that Papa Hemingway contained literary matter composed by Hemingway, for which he had a common-law copyright, and that publication would constitute an unauthorized appropriation of Hemingway’s work.

The Court dismissed the complaint, stating in part:

Conceivably, there may be limited and special situations in which an interlocutor brings forth oral statements from another party which both understand to be the unique intellectual product of the principal speaker, a product which would qualify for common-law copyright if such statements were in writing…

On the appeal before us, the plaintiffs’ claim to common-law copyright may be disposed of more simply and on a more narrow ground…

The defendant Hotchner asserts − without contradiction in the papers before us − that Hemingway never suggested to him or to anyone else that he regarded his conversational remarks to be ‘literary creations’ or that he was of a mind to restrict Hotchner’s use of the notes and recordings which Hemingway knew him to be accumulating. On the contrary, as we have already observed, it had become a continuing practice, during Hemingway’s lifetime, for Hotchner to write articles about Hemingway, consisting largely of quotations from the latter’s conversation − and of all of this Hemingway approved. In these circumstances, authority to publish must be implied, thus negativing the reservation of any common-law copyright.

Images:

Portrait of Ernest Hemingway photographed by Lloyd Arnold, 1939. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The New York Times, February 22, 1966. Copyright The New York Times

Photograph of Ernest and Mary Hemingway. Ernest Hemingway Collection. John F. Kennedy Presidential Library and Museum, Boston

Footnote:

1. Estate of Hemingway v. Random House, Inc., 23 N.Y.2d 341 (1968)

April 2017

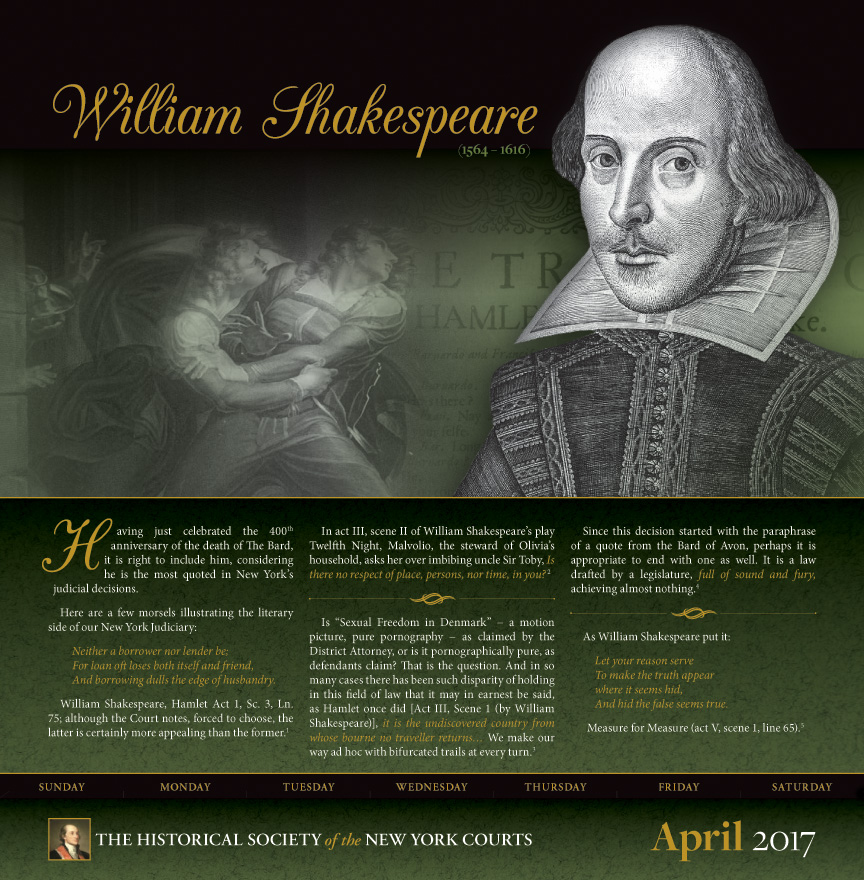

William Shakespeare (1564 -1616)

Having just celebrated the 400th anniversary of the death of The Bard, it is right to include him, considering he is the most quoted in New York’s judicial decisions.

Here are a few morsels illustrating the literary side of our New York Judiciary:

Neither a borrower nor lender be;

For loan oft loses both itself and friend,

And borrowing dulls the edge of husbandry.

William Shakespeare, Hamlet Act 1, Sc. 3, Ln. 75; although the Court notes, forced to choose, the latter is certainly more appealing than the former.1

***

In act III, scene II of William Shakespeare’s play Twelfth Night, Malvolio, the steward of Olivia’s household, asks her over imbibing uncle Sir Toby, Is there no respect of place, persons, nor time, in you?2

***

Is “Sexual Freedom in Denmark” − a motion picture, pure pornography − as claimed by the District Attorney, or is it pornographically pure, as defendants claim? That is the question. And in so many cases there has been such disparity of holding in this field of law that it may in earnest be said, as Hamlet once did [Act III, Scene 1 (by William Shakespeare)], it is the undiscovered country from whose bourne no traveller returns… We make our way ad hoc with bifurcated trails at every turn.3

***

Since this decision started with the paraphrase of a quote from the Bard of Avon, perhaps it is appropriate to end with one as well. It is a law drafted by a legislature, full of sound and fury, achieving almost nothing.4

***

As William Shakespeare put it:

Let your reason serve

To make the truth appear

where it seems hid,

And hid the false seems true.

Measure for Measure (act V, scene 1, line 65).5

Images:

Act 1, Scene 4 of Hamlet engraved by Robert Thew. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-115274

Manuscript page of Hamlet by William Shakespeare, 1632. By permission of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Photoengraving portrait of William Shakespeare, after engraving by Maerten Droeshout. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-80147

Footnotes:

1. MBNA Am. Bank, N.A. v. Nelson, 15 Misc. 3d 1148(A) (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 2007)

2. Park Slope Med. & Surgical Supply, Inc. v. MetLife Auto & Home, 35 Misc. 3d 686 (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 2012)

3. People v. Hilty, 67 Misc. 2d 67, 68 (N.Y. City Crim. Ct. 1971)

4. Malach v. Cheng Lung Chuang, 194 Misc. 2d 651, 666 (N.Y. Civ. Ct. 2002), see also, footnote 4: A paraphrase of Macbeth in William Shakespeare’s Macbeth, act V, scene 5

5. People v. Lalka, 113 Misc. 2d 474 (N.Y. City Ct. 1982)

May 2017

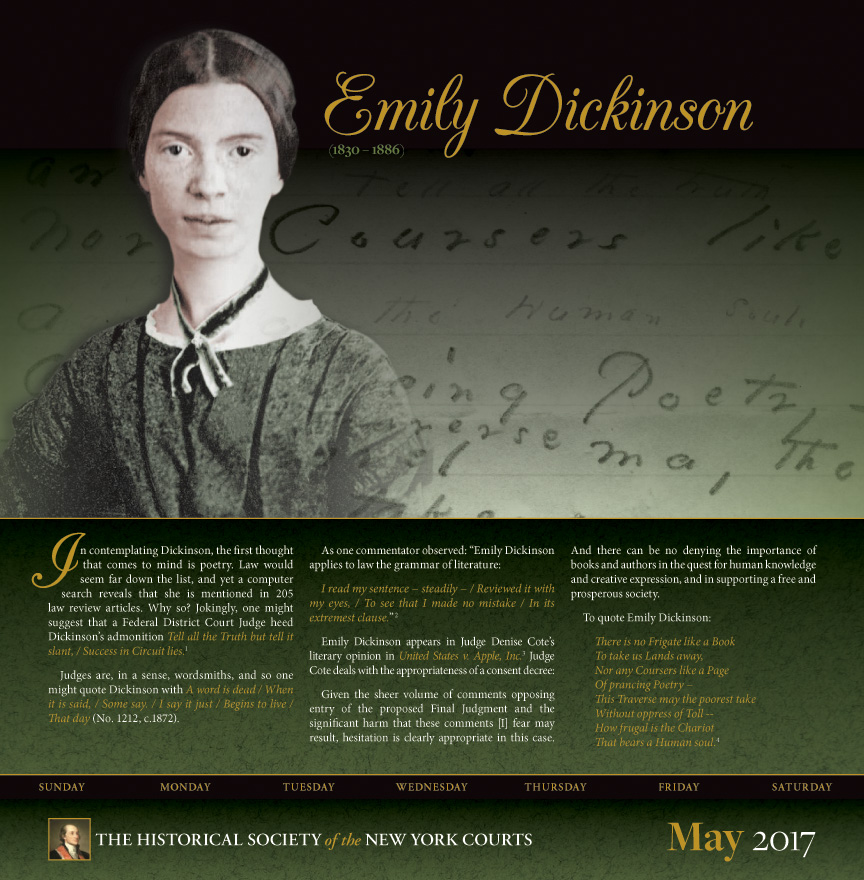

Emily Dickinson (1830 – 1886)

In contemplating Dickinson, the first thought that comes to mind is poetry. Law would seem far down the list, and yet a computer search reveals that she is mentioned in 205 law review articles. Why so? Jokingly, one might suggest that a Federal District Court Judge heed Dickinson’s admonition Tell all the Truth but tell it slant, / Success in Circuit lies.1

Judges are, in a sense, wordsmiths, and so one might quote Dickinson with A word is dead when it is said, some say. I say it just begins to live that day (No. 1212, c.1872).

As one commentator observed: “Emily Dickinson applies to law the grammar of literature: I read my sentence − steadily − / Reviewed it with my eyes, / To see that I made no mistake / In its extremest clause.”2

Emily Dickinson appears in Judge Denise Cote’s literary opinion in United States v. Apple, Inc.3 Judge Cote deals with the appropriateness of a consent decree:

Given the sheer volume of comments opposing entry of the proposed Final Judgment and the significant harm that these comments [I] fear may result, hesitation is clearly appropriate in this case. And there can be no denying the importance of books and authors in the quest for human knowledge and creative expression, and in supporting a free and prosperous society. To quote Emily Dickinson:

There is no Frigate like a Book

To take us Lands away,

Nor any Coursers like a Page

Of prancing Poetry −

This Traverse may the poorest take

Without oppress of Toll –

How frugal is the Chariot

That bears a Human soul.4

Images:

Daguerreotype of Emily Dickinson, 1847. Emily Dickinson Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections

“There is no frigate like a book” written by Emily Dickinson. Emily Dickinson Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections, Amherst Manuscript #462

“Tell All the Truth But Tell It Slant” written by Emily Dickinson. Emily Dickinson Collection, Amherst College Archives & Special Collections, Amherst Manuscript #372

Footnotes:

1. Dickinson, Emily. “Tell All the Truth But Tell It Slant,” Bolts of Memory 233 (M. Todd & M. Bingham eds. 1945)

2. Roberts, Alexandra J. “Constructing a Canon of Law-Related Poetry: Reviewing David Kader & Michael Stanford, eds. Poetry of Law: From Chaucer to

Present,” 90 Tex. L. Rev. 1507,1513 (2012)

3. 889 F. Supp. 2d 623 (S.D.N.Y. 2012)

4. Dickinson, Emily. “There is no Frigate like a Book (1263),” The Complete Poems of Emily Dickinson (Thomas H. Johnson ed., 1976)

June 2017

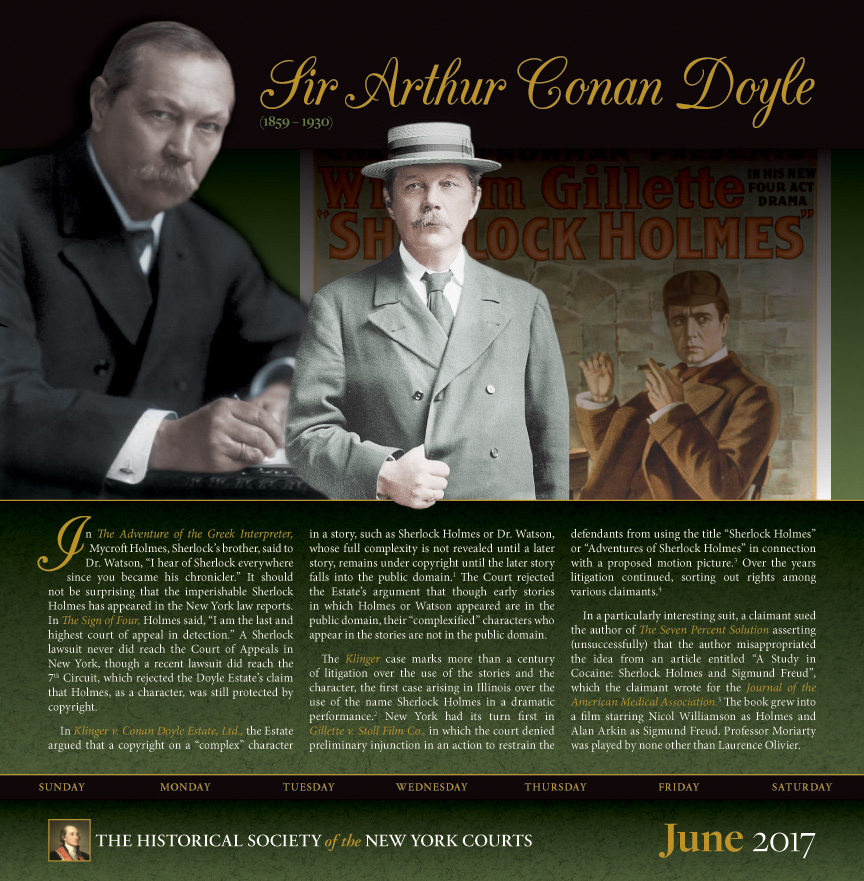

Sir Arthur Conan Doyle (1859 − 1930)

In The Adventure of the Greek Interpreter, Mycroft Holmes, Sherlock’s brother, said to Dr. Watson, “I hear of Sherlock everywhere since you became his chronicler.” It should not be surprising that the imperishable Sherlock Holmes has appeared in the New York law reports. In The Sign of Four, Holmes said, “I am the last and highest court of appeal in detection.” A Sherlock lawsuit never did reach the Court of Appeals in New York, though a recent lawsuit did reach the 7th Circuit, which rejected the Doyle Estate’s claim that Holmes, as a character, was still protected by copyright.

In Klinger v. Conan Doyle Estate, Ltd., the Estate argued that a copyright on a “complex” character in a story, such as Sherlock Holmes or Dr. Watson, whose full complexity is not revealed until a later story, remains under copyright until the later story falls into the public domain.1 The Court rejected the Estate’s argument that though early stories in which Holmes or Watson appeared are in the public domain, their “complexified” characters who appear in the stories are no in the public domain.

The Klinger case marks more than a century of litigation over the use of the stories and the character, the first case arising in Illinois over the use of the name Sherlock Holmes in a dramatic performance.2 New York had its turn first in Gillette v. Stoll Film Co., in which the court denied preliminary injunction in an action to restrain the defendants from using the title “Sherlock Holmes” or “Adventures of Sherlock Holmes” in connection with a proposed motion picture.3 Over the years litigation continued, sorting out rights among various claimants.4

In a particularly interesting suit, a claimant sued the author of The Seven Percent Solution asserting (unsuccessfully) that the author misappropriated the idea from an article entitled “A Study in Cocaine: Sherlock Holmes and Sigmund Freud”, which the claimant wrote for the Journal of the American Medical Association.5 The book grew into a film starring Nicol Williamson as Holmes and Alan Arkin as Sigmund Freud. Professor Moriarty was played by none other than Laurence Olivier.

Images:

Photograph of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-78587

Photograph of Sir Arthur Conan Doyle, 1913. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, George Grantham Bain Collection, LC-DIG-ggbain-12334

Charles Frohman presents William Gillette in his new four act drama, Sherlock Holmes. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZC2-1459

Footnotes:

1. 755 F.3d 496, 498 (7th Cir. Ill. 2014)

2. Hopkins Amusement Co. v. Frohman, 103 Ill. App. 613 (1902), aff’d, 67 N.E. 391 (1903)

3. 120 Misc. 850, 849-850 (N. Y. Sup. Ct. 1922), aff’d 206 A.D. 617 (1st Dept. 1923)

4. Granada Television Int’l, Inc. v. Lorindy Pictures Int’l, Inc., 606 F. Supp. 68, 73 (S.D.N.Y. 1984); Plunket v. Doyle, No. 99 Civ. 11006 (KMW), 2001 WL 175252 (S.D.N.Y. 2001); Pannonia Farms, Inc. v. USA Cable, 03 Civ. 7841 (NRB), 2004 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 23015 (S.D.N.Y. 2004)

5. Musto v. Meyer, 434 F. Supp. 32 (S.D.N.Y.1977), aff’d, 598 F.2d 609 (2d Cir. 1979)

July 2017

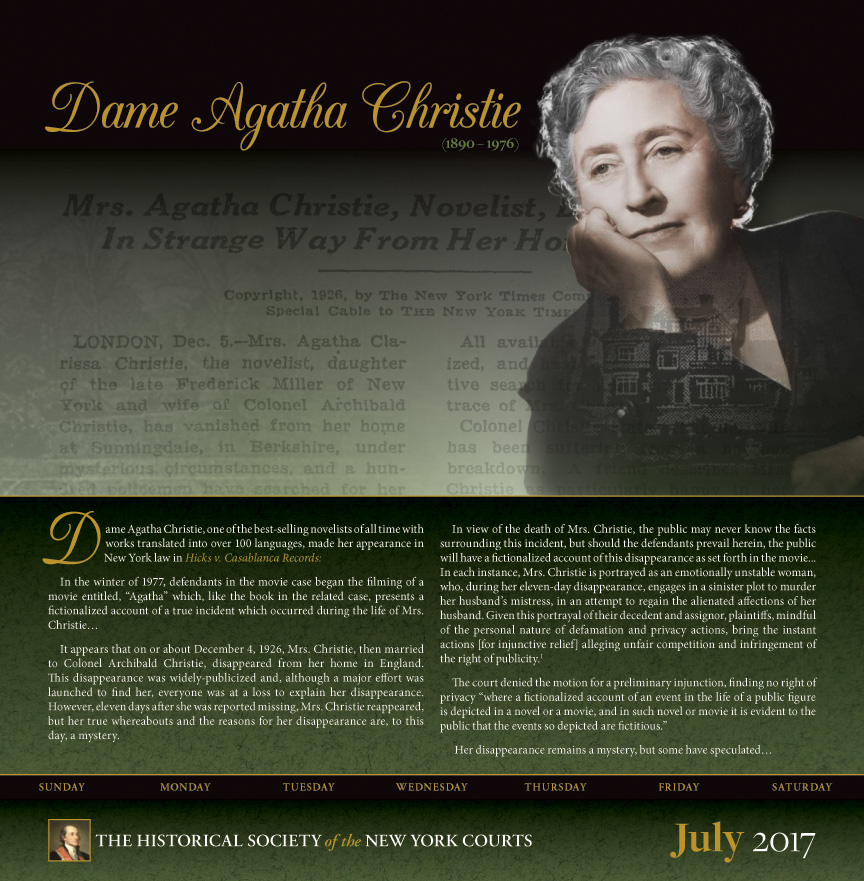

Dame Agatha Christie (1890 – 1976)

Dame Agatha Christie, one of the best-selling novelists of all time with works translated into over 100 languages, made her appearance in New York law in Hicks v. Casablanca Records:

In the winter of 1977, defendants in the movie case began the filming of a movie entitled, “Agatha” which, like the book in the related case, presents a fictionalized account of a true incident which occurred during the life of Mrs. Christie…

It appears that on or about December 4, 1926, Mrs. Christie, then married to Colonel Archibald Christie, disappeared from her home in England. This disappearance was widely-publicized and, although a major effort was launched to find her, everyone was at a loss to explain her disappearance. However, eleven days after she was reported missing, Mrs. Christie reappeared, but her true whereabouts and the reasons for her disappearance are, to this day, a mystery.

In view of the death of Mrs. Christie, the public may never know the facts surrounding this incident, but should the defendants prevail herein, the public will have a fictionalized account of this disappearance as set forth in the movie… In each instance, Mrs. Christie is portrayed as an emotionally unstable woman, who, during her eleven-day disappearance, engages in a sinister plot to murder her husband’s mistress, in an attempt to regain the alienated affections of her husband. Given this portrayal of their decedent and assignor, plaintiffs, mindful of the personal nature of defamation and privacy actions, bring the instant actions [for injunctive relief] alleging unfair competition and infringement of the right of publicity.1

The court denied the motion for a preliminary injunction, finding no right of privacy “where a fictionalized account of an event in the life of a public figure is depicted in a novel or a movie, and in such novel or movie it is evident to the public that the events so depicted are fictitious.”

Her disappearance remains a mystery, but some have speculated…

Images:

The Times (London, England), May 17, 1927. Copyright The Times

Case opinion. Courtesy of the Court of Appeals

Angus McBean Photograph (MS Thr 581, olvworks572171) © Houghton Library, Harvard University

The Times (London, England), March 2, 1928. Copyright the Times

Footnote:

1. 464 F. Supp. 426, 429 (S.D.N.Y. 1978)

August 2017

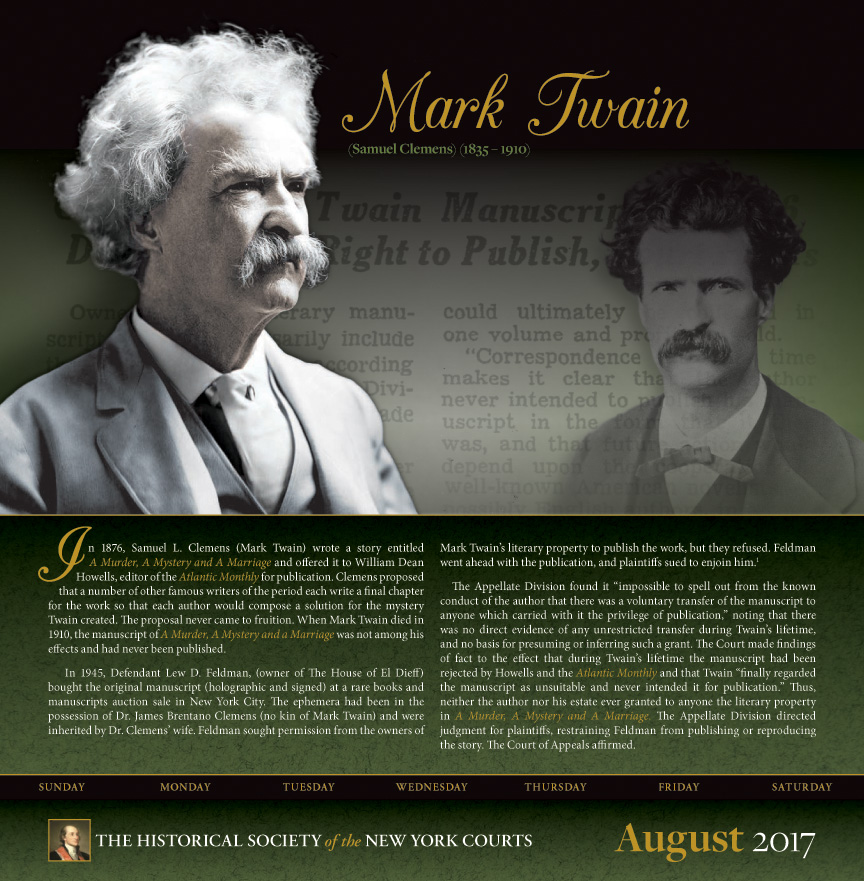

Mark Twain (Samuel Clemens) (1835 – 1910)

In 1876, Samuel L. Clemens (Mark Twain) wrote a story entitled A Murder, A Mystery and A Marriage and offered it to William Dean Howells, editor of the Atlantic Monthly for publication. Clemens proposed that a number of other famous writers of the period each write a final chapter for the work so that each author would compose a solution for the mystery Twain created. The proposal never came to fruition. When Mark Twain died in 1910, the manuscript of A Murder, A Mystery and A Marriage was not among his effects and had never been published.

In 1945, Defendant Lew D. Feldman, (owner of The House of El Dieff) bought the original manuscript (holographic and signed) at a rare books and manuscripts auction sale in New York City. The ephemera had been in the possession of Dr. James Brentano Clemens (no kin of Mark Twain) and were inherited by Dr. Clemens’ wife. Feldman sought permission from the owners of Mark Twain’s literary property to publish the work, but they refused. Feldman went ahead with the publication, and plaintiffs sued to enjoin him.1

The Appellate Division found it “impossible to spell out from the known conduct of the author that there was a voluntary transfer of the manuscript to anyone which carried with it the privilege of publication,” noting that there was no direct evidence of any unrestricted transfer during Twain’s lifetime, and no basis for presuming or inferring such a grant. The Court made findings of fact to the effect that during Twain’s lifetime the manuscript had been rejected by Howells and the Atlantic Monthly and that Twain “finally regarded the manuscript as unsuitable and never intended it for publication.” Thus, neither the author nor his estate ever granted to anyone the literary property in A Murder, A Mystery and A Marriage. The Appellate Division directed judgment for plaintiffs, restraining Feldman from publishing or reproducing the story. The Court of Appeals affirmed.

Images:

Photograph of Mark Twain, 1907. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-5513

The New York Times, January 19, 1949. Copyright The New York Times

Carte de visite of Mark Twain by Abdullah Freres, 1867. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-28851

Footnote:

1. Chamberlain v. Feldman, 274 A.D. 515 (1st Dept. 1948), aff’d 300 N.Y. 135 (1949)

September 2017

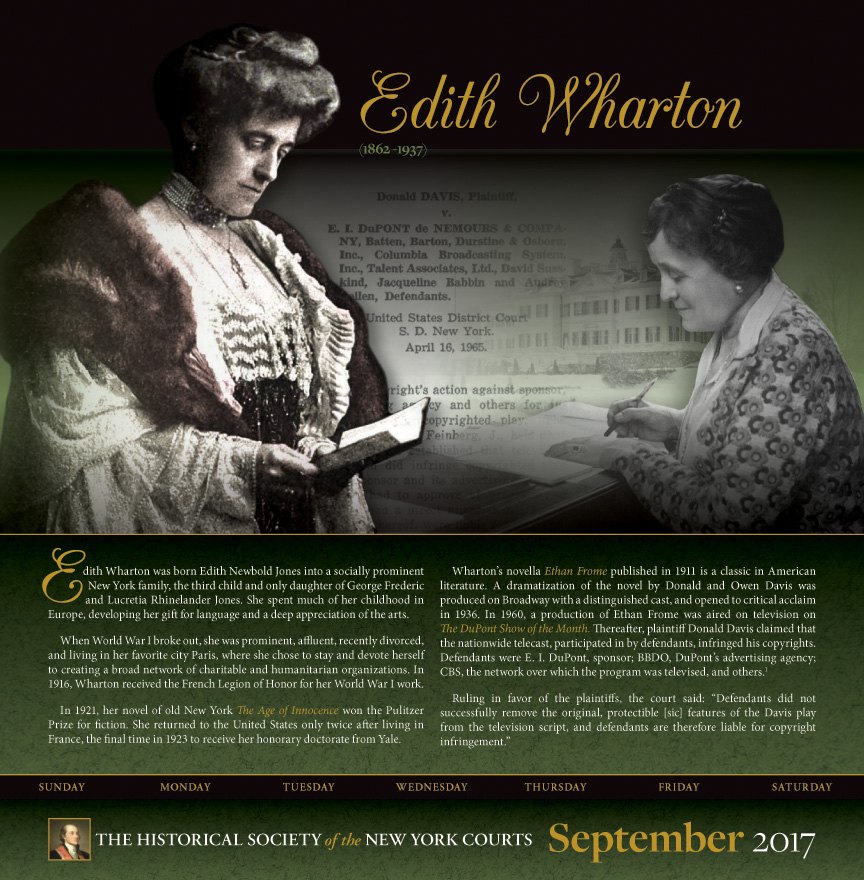

Edith Wharton (1862 -1937)

Edith Wharton was born Edith Newbold Jones into a socially prominent New York family, the third child and only daughter of George Frederic and Lucretia Rhinelander Jones. She spent much of her childhood in Europe, developing her gift for language and a deep appreciation of the arts.

When World War I broke out, she was prominent, affluent, recently divorced, and living in her favorite city Paris, where she chose to stay and devote herself to creating a broad network of charitable and humanitarian organizations. In 1916, Wharton received the French Legion of Honor for her World War I work.

In 1921, her novel of old New York The Age of Innocence won the Pulitzer Prize for fiction. She returned to the United States only twice after living in France, the final time in 1923 to receive her honorary doctorate from Yale.

Wharton’s novella Ethan Frome published in 1911 is a classic in American literature. A dramatization of the novel by Donald and Owen Davis was produced on Broadway with a distinguished cast, and opened to critical acclaim in 1936. In 1960, a production of Ethan Frome was aired on television on The DuPont Show of the Month. Thereafter, plaintiff Donald Davis claimed that the nationwide telecast, participated in by defendants, infringed his copyrights. Defendants were E. I. DuPont, sponsor; BBDO, DuPont’s advertising agency; CBS, the network over which the program was televised, and others.1

Ruling in favor of the plaintiffs, the court said: “Defendants did not successfully remove the original, protectible [sic] features of the Davis play from the television script, and defendants are therefore liable for copyright infringement.”

Images:

Photograph of Edith Wharton. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-29408

Case opinion. Courtesy of the Court of Appeals

Photograph of Edith Wharton’s estate, The Mount, c. 1906. Edith Wharton Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Photograph of Edith Wharton, c. 1920. Edith Wharton Collection. Yale Collection of American Literature. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Footnote:

1. Davis v. E. I. DuPont de Nemours & Co., 240 F. Supp. 612, 622 (S.D.N.Y. 1965)

October 2017

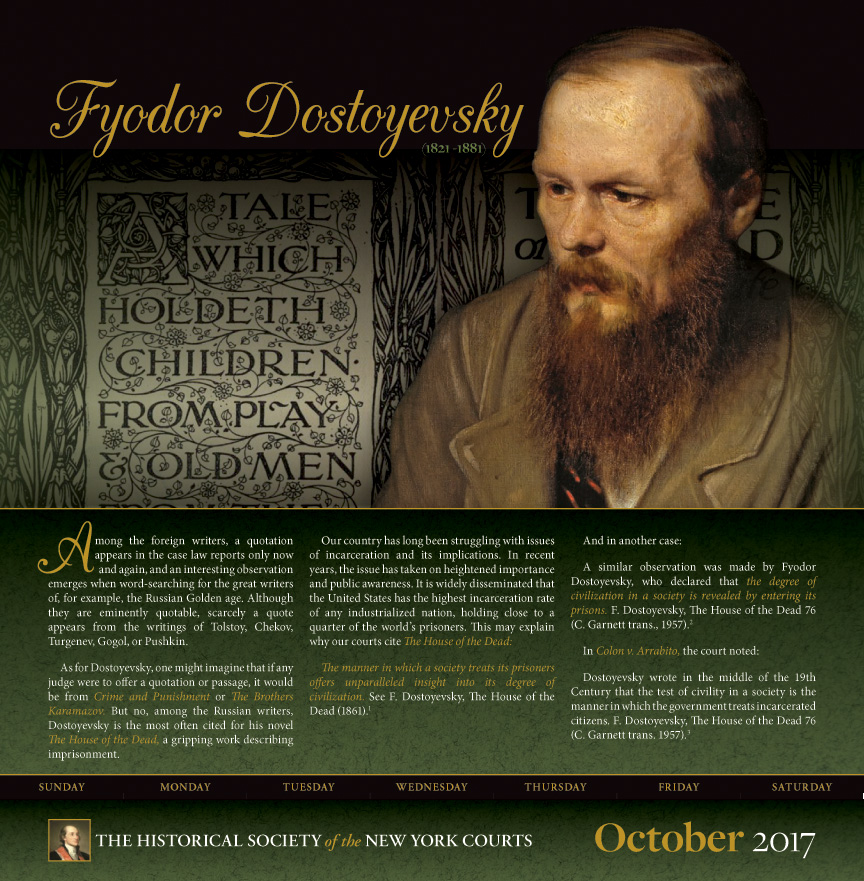

Fyodor Dostoyevsky (1821 -1881)

Among the foreign writers, a quotation appears in the case law reports only now and again, and an interesting observation emerges when word-searching for the great writers of, for example, the Russian Golden age. Although they are eminently quotable, scarcely a quote appears from the writings of Tolstoy, Chekov, Turgenev, Gogol, or Pushkin.

As for Dostoyevsky, one might imagine that if any judge were to offer a quotation or passage it would be from Crime and Punishment or The Brothers Karamazov. But no, among the Russian writers, Dostoyevsky is the most often cited for his novel The House of the Dead, a gripping work describing imprisonment.

Our country has long been struggling with issues of incarceration and its implications. In recent years, the issue has taken on heightened importance and public awareness. It is widely disseminated that the United States has the highest incarceration rate of any industrialized nation, holding close to a quarter of the world’s prisoners. This may explain why our courts cite The House of the Dead:

The manner in which a society treats its prisoners offers unparalleled insight into its degree of civilization. See F. Dostoyevsky, The House of the Dead (1861).1

And in another case:

A similar observation was made by Fyodor Dostoyevsky, who declared that the degree of civilization in a society is revealed by entering its prisons. F. Dostoyevsky, The House of the Dead 76 (C. Garnett trans., 1957).2

In Colon v. Arrabito, the court noted:

Dostoyevsky wrote in the middle of the 19th Century that the test of civility in a society is the manner in which the government treats incarcerated citizens. F. Dostoyevsky, The House of the Dead 76 (C. Garnett trans. 1957).3

Images:

Oil painting of Fyodor Dostoyevsky by Vasily Perov, 1872. Courtesy of Google Arts & Culture, Tretyakov Gallery, Moscow, Russia

Cover of The House of the Dead, 1911. Courtesy of The Internet Archive

Footnotes:

1. Handberry v. Thompson, 92 F. Supp. 2d 244, 248 (S.D.N.Y. 2000)

2. United States v. Speed Joyeros, 204 F. Supp. 2d 412 (E.D.N.Y. 2002); see, also Benjamin v. Jacobson, 935 F. Supp. 332 (S.D.N.Y. 1996)

3. 1998 U.S. Dist. LEXIS 8484, 13-14 (S.D.N.Y. 1998)

November 2017

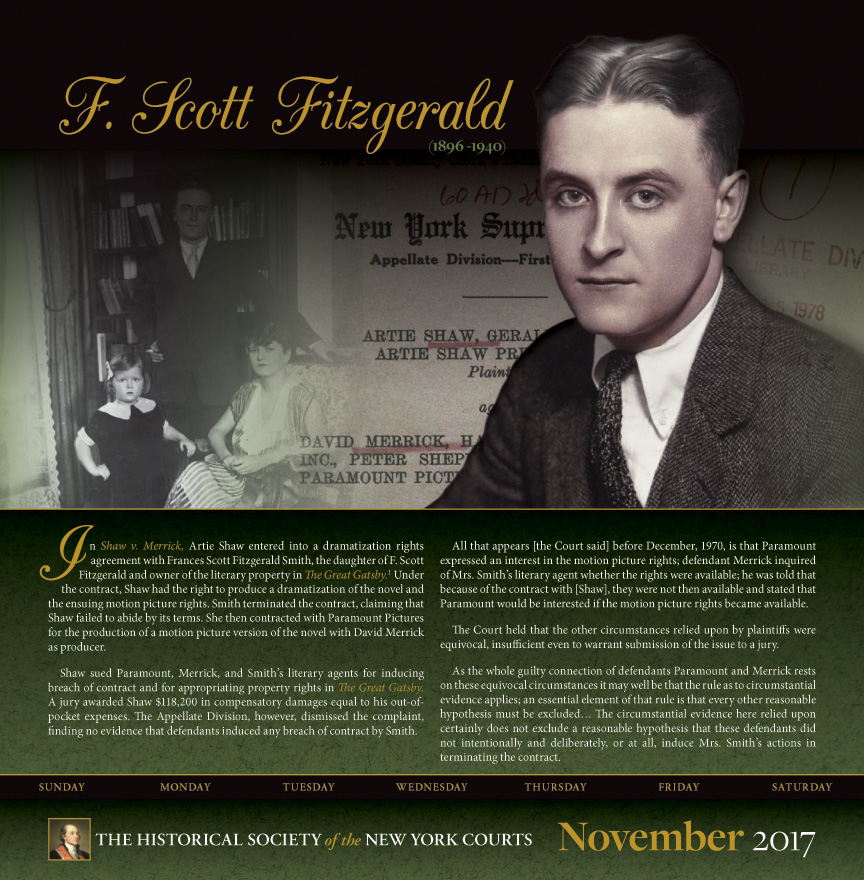

F. Scott Fitzgerald (1896 -1940)

In Shaw v. Merrick, Artie Shaw entered into a dramatization rights agreement with Frances Scott Fitzgerald Smith, the daughter of F. Scott Fitzgerald and owner of the literary property in The Great Gatsby.1 Under the contract, Shaw had the right to produce a dramatization of the novel and the ensuing motion picture rights. Smith terminated the contract, claiming that Shaw failed to abide by its terms. She then contracted with Paramount Pictures for the production of a motion picture version of the novel with David Merrick as producer.

Shaw sued Paramount, Merrick, and Smith’s literary agents for inducing breach of contract and for appropriating property rights in The Great Gatsby. A jury awarded Shaw $118,200 in compensatory damages equal to his out-of-pocket expenses. The Appellate Division, however, dismissed the complaint, finding no evidence that defendants induced any breach of contract by Smith.

All that appears [the Court said]before December, 1970, is that Paramount expressed an interest in the motion picture rights; defendant Merrick inquired of Mrs. Smith’s literary agent whether the rights were available; he was told that because of the contract with [Shaw], they were not then available and stated that Paramount would be interested if the motion picture rights became available.

The Court held that the other circumstances relied upon by plaintiffs were equivocal, insufficient even to warrant submission of the issue to a jury.

As the whole guilty connection of defendants Paramount and Merrick rests on these equivocal circumstances it may well be that the rule as to circumstantial evidence applies; an essential element of that rule is that every other reasonable hypothesis must be excluded… The circumstantial evidence here relied upon certainly does not exclude a reasonable hypothesis that these defendants did not intentionally and deliberately, or at all, induce Mrs. Smith’s actions in terminating the contract.

Images:

Photograph of F. Scott Fitzgerald with wife Zelda Sayre Fitzgerald and daughter Frances Scott Fitzgerald, who was involved in the case. F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers (C0187), Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Case file cover for Shaw v. Merrick. Courtesy of the Appellate Division, First Department

Photograph of F. Scott Fitzgerald, 1921. F. Scott Fitzgerald Papers (C0187), Manuscripts Division, Department of Rare Books and Special Collections, Princeton University Library

Footnote:

1. 60 A.D.2d 830, 830-831 (1st Dept. 1978)

December 2017

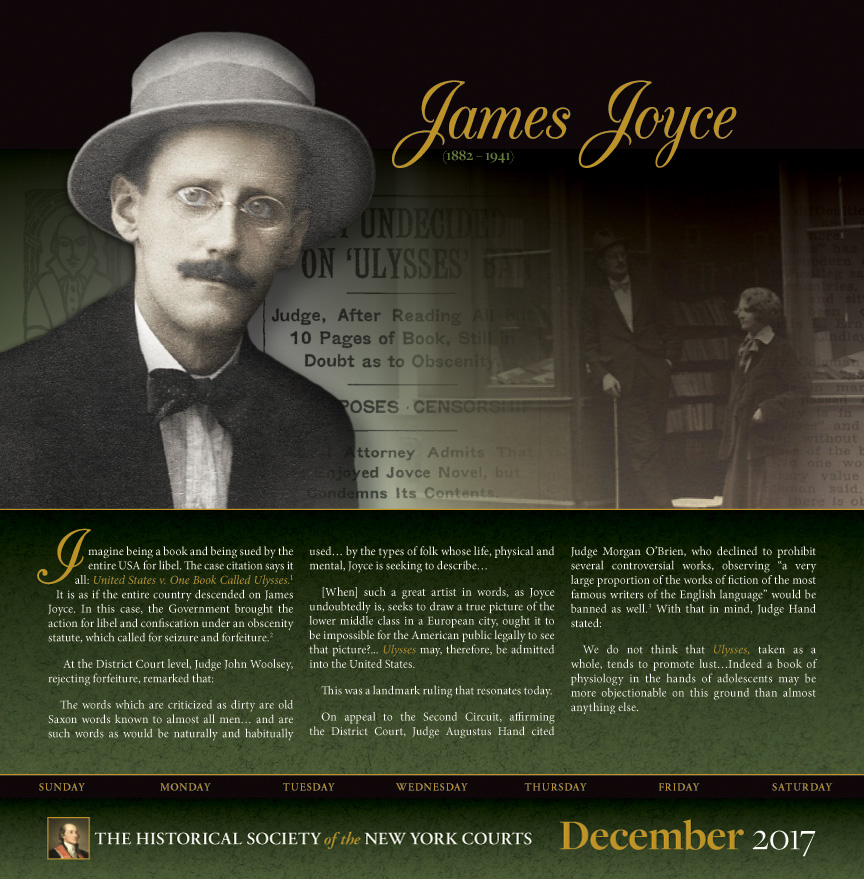

James Joyce (1882 – 1941)

Imagine being a book, and being sued by the entire USA for libel. The case citation says it all: United States v. One Book Called Ulysses.1 It is as if the entire country descended on James Joyce. In this case, the Government brought the action for libel and confiscation under an obscenity statute, which called for seizure and forfeiture.2

At the District Court level, Judge John Woolsey, rejecting forfeiture, remarked that:

The words which are criticized as dirty are old Saxon words known to almost all men… and are such words as would be naturally and habitually used… by the types of folk whose life, physical and mental, Joyce is seeking to describe…

[When] such a great artist in words, as Joyce undoubtedly is, seeks to draw a true picture of the lower middle class in a European city, ought it to be impossible for the American public legally to see that picture?…

“Ulysses” may, therefore, be admitted into the United States.

This was a landmark ruling that resonates today.

On appeal to the Second Circuit, affirming the District Court, Judge Augustus Hand cited Judge Morgan O’Brien, who declined to prohibit several controversial works, observing “a very large proportion of the works of fiction of the most famous writers of the English language” would be banned as well.3 With that in mind, Judge Hand stated:

We do not think that Ulysses, taken as a whole, tends to promote lust…Indeed a book of physiology in the hands of adolescents may be more objectionable on this ground than almost anything else.

Images:

Advertisement for Ulysees by James Joyce, c. 1920. Beinecke Rare Book and Manuscript Library, Yale University

Carte de visite of James Joyce by Alex Ehrenzweig, 1915. Courtesy of Wikimedia Commons

The New York Times, November 26, 1933. Copyright The New York Times

Photograph of James Joyce and Sylvia Beach in front of Shakespeare and Company. Courtesy of the Poetry Collection, SUNY at Buffalo

Footnotes:

1. 5 F. Supp. 182 (S.D.N.Y. 1933), aff’d sub nom. United States v. One Book Entitled Ulysses by James Joyce, 72 F.2d 705 (2d Cir. 1934)

2. Section 305 (a) of the Tariff Act of 1930 (19 USC § 1305 (a)

3. In re Worthington Co., (Sup.) 30 N.Y.S. 361, 362, 24 L.R.A 110