In 1852, the Third Avenue Railroad Company obtained a franchise to construct and operate a street railway service in parts of Manhattan. The company installed steel rails in the surface of some Manhattan streets and, in July 1853, began a streetcar service consisting of carriages pulled along these rails by horses. Passengers could board or leave the carriages at various points along the route. Some carriages carried a placard “Colored Persons Allowed,” but these carriages ran infrequently and African-Americans were often permitted to board the general streetcars at the discretion of the driver and conductor, provided none of the other passengers objected.

On July 16, 1854, a 24 year old African-American school teacher named Elizabeth Jennings and her friend, Sarah Adams, were on their way to church when they hailed a Third Avenue Railroad Company streetcar. It did not have a placard, and the women were immediately challenged by the conductor. Elizabeth refused to disembark and the streetcar continued on its route until the conductor sighted a police officer and requested his assistance. Between them, the two men roughly removed Elizabeth from the streetcar, and she found herself on the sidewalk with her “bonnet smashed and her dress soiled.”

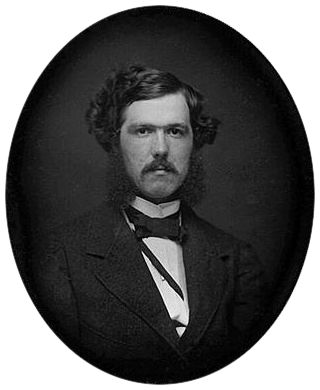

With support from the Black community, Elizabeth retained the (white) law firm of Culver, Parker and Arthur to represent her in a lawsuit against the Third Avenue Railway Company. The firm’s junior partner, Chester A. Arthur, had recently been admitted to the bar and the case was assigned to him. At the jury trial in Brooklyn (the headquarters of the company were located in Brooklyn), Arthur argued that provisions recently enacted in the Revised Statutes relating to common carriers applied to the case, and Brooklyn Circuit Court Judge William Rockwell instructed the jury that, “under the law, colored persons, if sober, well behaved and free from disease, had the right to ride the streetcars” and “could neither be excluded by any rules of the Company, nor by force or violence.” The all-male, all-white jury found for the plaintiff and awarded her damages of $225. She was also awarded $22.50 in costs. More importantly, the Third Avenue Railroad Company agreed to the immediate desegregation of its streetcar service.

Other streetcar companies, however, retained segregated services and Elizabeth’s father, Thomas Jennings, an influential member of New York’s Black community and a successful businessman, founded the Legal Rights Association to challenge racial segregation in public transportation. By 1861, all New York public transit was desegregated.

In the historical context, Elizabeth Jennings’s bravery and her remarkable legal victory took place six years before the outbreak of the Civil War and 100 years before Rosa Parks’ protest against racial discrimination on a bus in Montgomery, Alabama.

The importance of Elizabeth Jennings’s case is two-fold: The strategy of the Legal Rights Association became a model for later civil rights organizations through its use of public-opinion campaigns, lobbying, civil disobedience and litigation to effect change. The case was also important because it was the starting point in the career of 24-year-old Chester Arthur who went on to become America’s 21st President (1881-85).

SOURCES

Thomas Reeves. The Gentleman Boss (2013)

Katherine Greider. The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar, New York Times 11/13/2005.

Leslie Alexander (ed.) Encyclopedia of African American History (2010)

New York Tribune. Outrage Upon Colored Persons, July 19, 1854, 7:2

New York Tribune. A Wholesome Verdict, February 23, 1855, 7:4.

Frederick Douglass’ Paper, July 28, 1854

Comments · 3

Comments are closed.