In 1937, Judge Irving Hubbs, then in his eighth year as a judge of the Court of Appeals, made one of the court’s most important pronouncements when upholding the constitutionality of a statute abolishing causes of action for alienation of affections and criminal conversation (adultery): “A wife,” he wrote in Hanfgarn v. Mark,1 “is no longer the property of her husband in the eyes of the law and by the general acceptance of society.” In as much as the statute abolished causes of action by both husbands and wives, it is evident that Judge Hubbs went out of his way to couch his language as he did, and it stands out as a hallmark of things to come.

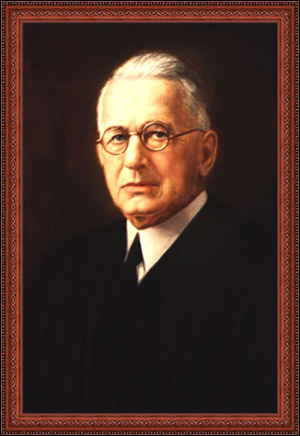

Irving George Hubbs was born on November 18, 1870 in Sandy Creek, Oswego County, New York. His father, George L. Hubbs (1841-1922), the son of Cyrus Hubbs of Jonesville, Saratoga County, was a civil war veteran who at age 19 enlisted in the Second Wisconsin Volunteers, before returning to Sandy Creek, his birthplace. Irving’s mother, Catherine Snyder Hubbs (1843-1900), and father were prominent local citizens. His father was a merchant and in the hotel business. Irving had two younger siblings, a brother, Wesley Jay, born in 1873, and a sister, Zella May (Mrs. Albert K. Box), born in 1876. (Some accounts say 1899; others, 1900.)

Young Irving graduated from Pulaski Academy with the class of 1888, acquiring his taste for the law while working summers in the office of District Attorney Don A. King of Pulaski. From there, he entered Cornell in 1888, completing a course in law in 1891, marking a loyal relationship with the school and his classmates that continued throughout his life. On November 19, 1891, the day after his 21st birthday, Hubbs was admitted to the bar, in Syracuse. It was not long before he began to establish himself in the local community that counted the Hubbs family among its first citizens.

On January 5, 1893, he married his high school sweetheart Nancy (Nannie) Dixson (b. 1870), the daughter of William Brainanrd Dixson, a Pulaski businessman. The Pulaski Democrat reported on the wedding, calling it a memorable social event, held at the bride’s father’s home on Jefferson Avenue in Pulaski. “The bride, by common consent, was declared never to have been more charmingly attractive than on this occasion.” The couple was said to have departed on the 7:25 train to New York. One suspects that the Hubbs’ liked it there; several years later Judge Hubbs, then on the State Supreme Court, meticulously recorded his assignment there and kept clippings of his New York City cases. The young marrieds began their married lives together in the Village of Parish, Oswego County, where Hubbs had started his law practice in 1891 in the Pulaski National Bank building. Judge Hubbs’ rise to prominence began almost immediately. In 1893, the year of his marriage, he was elected Special County Judge of Oswego County, and in 1894 the couple moved to Pulaski. In 1896, he was reelected.

In 1911, Hubbs was mentioned in a New York Times article describing the Supreme Court election for the fifth judicial district. “Few campaigns have aroused as much interest in this section as the judicial fight in the Fifth District between Henry Purcell and E.C. Emerson of this city [Watertown] and Irving Hubbs of Oswego . . .” for two vacant seats. “Tammary money has poured into [Jefferson County] in greater sums than ever before.”2 If so, it was not enough to defeat Judge Hubbs, who at age 41 would take his Supreme Court seat at the beginning of 1912, after spending $289.00,3 (more than three times the amount he spent for his Court of Appeals campaign 16 years later).

Apparently of shy disposition, Judge Hubbs slowly adapted to public life. As a special guest of the Rochester Bar Association, he was asked but “was too modest to make a speech.” Instead, at the behest of the association president, Judge Hubbs shook hand with every lawyer present and “bore up under the strain amazingly well, and rather seemed to enjoy the experience.”4 That year, another Rochester newspaper article reported that “Living away off in Pulaski, Oswego County, [Judge Hubbs] naturally feels a little shy of newspaper men5. But that will wear off.”6

As a Supreme Court Justice, Hubbs often expressed his concerns publicly about court delays caused by cases not worthy of litigation.7 At the same time, he continued his civil commitments, serving as head of the Pulaski branch of the American Red Cross.

In 1918, Governor Whitman appointed Judge Hubbs to the Appellate Division, Fourth Department to replace Judge Edgar S.K. Merrell of Lowville, Lewis County who was transferred to the First Department. The news was received editorially as a mixed blessing: disappointment at losing Judge Hubbs to the Appellate Division, and high praise for his advancement. The Syracuse Herald of May 9, 1918 had this to say:

The regret will be inspired by the reflection that the Fifth district must lose an exceptionally well-equipped trial judge. In that capacity Justice Hubbs has won golden opinions since his advent on the bench in January, 1912. He has, in fact, been a model presiding magistrate; quick and keen as well as just in his decisions, courteous and dignified in deportment, and, in short, vindicating in every respect of his judicial record the favorable promise of his candidacy before the people in the memorable campaign of 1911 — a candidacy the Herald was glad to support. . . . [W]e must selfishly hail his promotion as a deserving reward for a wise, learned and faithful judge.

Newspapers joined in the praise.8 Judge Hubbs was so beloved and respected by the people of his region that an editorial of the March 31, 1920 Pulaski Democrat (remember that Hubbs had been an active Republican) proclaimed that he should guide local folks in whom to support in the forthcoming presidential election. Judge Hubbs’ “calling and election” being assured, he would be the impartial and trustworthy voice on whom the voters could rightfully depend. Higher praise is almost unimaginable, even in 1920.9

Judge Hubbs continued to advance, and in January 1923, Governor Alfred E. Smith named him to succeed Frederick W. Kruse as presiding justice of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department. Hubbs was only 52 and the first from Oswego County ever to hold the honor. Editorial writers cheered the choice, as they did two years later when he was renominated and cross-endorsed cheerfully by the Democrats for Supreme Court in 1925, remaining on the Appellate Division as presiding justice.10

Judge Hubbs compiled an admirable and productive record on the Appellate Division, on which he served for eleven years, authoring 139 opinions and joining in on hundreds of others.

In February 1928, political parties began considering candidates for a vacancy on the Court of Appeals to replace Judge William S. Andrews who was to retire on December 31, 1928 on account of New York’s constitutional 70-year-old age limit. Interestingly, a contest developed between Republican Judge Hubbs and Judge Leonard C. Crouch, the Democratic nominee. The two were both serving on the Appellate Division, Fourth Department.

On the very day Governor Smith named Judge Hubbs presiding justice of the Fourth Department, he elevated Judge Crouch to that Court. In a Syracuse Post-Standard article datelined December 9, 1922, the newspaper reported on the joint advancement, featuring photographs of the two. Both were Cornell graduates and, one imagines, friends and colleagues on the Appellate Division when nominated to oppose one another in the November 1928 election for a seat on the Court of Appeals.

Initially, there was talk of a joint Republican-Democrat nomination, so as to continue the policy “keeping the Court of Appeals bench out of politics” after the fashion of the cross-nomination of Judge John F. O’Brien, a Democrat, and the 1926 cross-endorsement of Chief Judge Benjamin Cardozo, a Democrat, and Associate Judge Henry T. Kellogg, a Republican.11

A cross-endorsement, however, was not in the cards. Judges Hubbs and Crouch would face off against one another in what turned out to be an excruciatingly close election. The Republicans nominated Judge Hubbs over Judge Charles B. Sears of Buffalo,12 but the Democrats would not cross-endorse, and nominated Judge Crouch.

It would be fanciful to pretend that the election was close because the public was almost equally divided based on the merits of these two first-rate judges. Like most other judicial elections, however, it was based, no doubt, on a party line vote in which only a fraction of the voters knew anything at all about the judicial candidates.

The early New York City returns gave the lead to Judge Crouch, on the ticket with Alfred E. Smith, who faced Herbert Hoover, the Republican, for President. Also on the ballot was Franklin Delano Roosevelt, running for Governor against Republican Albert Ottinger. Albert Conway was the Democratic candidate for Attorney General. With over 3,000 districts yet to report, Judge Crouch led Judge Hubbs 1,406,016 to 1,155,662.13 As more votes were tallied, with 362 upstate districts yet to be counted, Judge Crouch led by 1,885,603 to 1,882,584.14 After the dust cleared (and the upstate votes counted), Hubbs won by 59,355 votes.15 Hoover and FDR also prevailed. Not to be denied, Judge Crouch was appointed to the Court of Appeals by Governor FDR in 1933 to fill a vacancy resulting from the appointment of Chief Judge Cardozo to the United States Supreme Court. Crouch was elected to the Court of Appeals in November of that year, serving through 1936; Charles B. Sears was appointed to the Court and served in 1940; Albert Conway was appointed to the Court in 1940, elected in November of that year, then was elected Chief Judge in November 1954, serving through 1959.

In the end, the public was well served; Judges Hubbs and Crouch were colleagues on the Court of Appeals, overlapping from 1933 until the end of 1936, when Judge Crouch reached mandatory retirement.

The November 1928 election in which they faced one another was anything but heated. In contrast to some of today’s high court elections in other states, in which millions are lavished on blistering campaigns, the 1928 contest involved no advertising or the like. Judge Hubbs reported his total campaign expenditures as $79.50.16 We do not know Judge Crouch’s expenses; it was no doubt of the same tenor. This writer imagines the two colleagues politely awaiting the returns, like the gentlemen they were, exchanging good-natured remarks.

Judge Hubbs served on the Court for ten years, a distinguished member of benches that included Judges Benjamin Cardozo (although for only about two months, as Cardozo left for the United States Supreme Court), Cuthbert W. Pound, Irving Lehman, Frederick E. Crane, and John T. Loughran.

During that decade of service Judge Hubbs authored 246 majority writings, including some significant ones. In Kirke La Shelle Co. v. Paul Armstrong Co.17 he first expressed the contractual duty of good faith performance.18 There, the defendants granted plaintiff a half interest in a certain play and then sold the “talkie” rights to a third party. Judge Hubbs framed the relevant issue as “whether there should be implied in the contract . . . a covenant on the part of the [defendants] not to do anything to destroy or ignore [plaintiff’s] rights under the contract.”19 He noted that “[b]y entering into the contract and accepting and retaining the consideration therefor, the [defendants] assumed a fiduciary relationship which had its origin in the contract, and which imposed upon them the duty of utmost good faith.”20 There, there was, he said, an implied obligation on the part of the defendants not to extinguish the right conferred by the contract.21

In Hornstein v. Podwitz,22 Judge Hubbs discussed the interrelationship between a plaintiff’s causes of action sounding in breach of contract and the tort of inducing one. Concluding that a plaintiff could seek damages from both the party who breached the contract and the party who induced that breach, he explained that the party inducing the breach

committed a legal wrong which gave rise to a cause of action in favor of the plaintiff. The fact that the plaintiff also has a cause of action against his principal for breach of contract does not prevent his having a cause of action in tort against [the party inducing the breach]. [It] cannot be heard to say that [it is] not liable for [its] wrongful act because [the party who breached the contract] is also liable to the plaintiff.23

In a four-month period, Judge Hubbs authored two opinions upholding the constitutionality of portions of a statute that abolished the “Heart Balm” common law causes of action. In 1935, the Legislature abolished alienation of affections, criminal conversation, seduction, and breach of promise to marry, as violative of public policy. Speaking for the Court in Fearon v. Treanor,24 Judge Hubbs declared constitutional that part of the statute abolishing the cause of action for breach of promise to marry. He wrote that

[t]he Legislature, acting within its authority, has determined as a matter of public policy that marriages should not be entered into because of the threat or danger of an action to recover money damages and the embarrassment and humiliation growing out of such an action. We are convinced that the Legislature, in passing the statute, acted within its constitutional power to regulate the marriage relation for the public welfare.25

Shortly thereafter, in the alienation of affections and criminal conversation* case (Hanfgarn v. Mark26), Judge Hubbs wrote:

“[i]n view of the broad and almost unlimited extension of the rights of married women brought about by statutory enactments and social advancement, we think that no court in this state would decide that the rights which a husband has by virtue of the marriage relation constitute property rights. A wife is no longer the property of her husband in the eyes of the law and by the general acceptance of society.”27

In People ex rel. Mooney v. Sheriff of New York County,28 Judge Hubbs held that no privilege existed granting newspaper reporters a right to refuse to disclose communications with sources to a grand jury. He noted that several legislative attempts to create such a privilege failed and that “[t]he policy of the law is to require the disclosure of all information by witnesses in order that justice may prevail. . . . The tendency is not to extend the classes to whom the privilege from disclosure is granted, but to restrict that privilege.”29 Accordingly, he said, “this court should not now depart from the general rule . . . and create a privilege in favor of an additional class. If that is to be done, it should be done by the Legislature.”30 (Eventually, the Legislature extended certain privileges to news media personnel (see Civil Rights Law ‘ 79-h).)

Judge Hubbs had occasion to discuss the hearsay rule’s business records exception in Johnson v. Lutz,31 one of the most frequently cited cases in this or any other field. The trial court had excluded a police officer’s accident report “made from hearsay statements of third persons who happened to be present at the scene of the accident when [the police officer] arrived.”32 Judge Hubbs affirmed the exclusion of the report, concluding that the business records exception “was not intended to permit the receipt in evidence of entries based upon voluntary hearsay statements made by third parties not engaged in the business or under any duty in relation thereto.”33

Serving on the Court during the Great Depression, Judge Hubbs heard appeals challenging the constitutionality of depression-era social legislation. In W. H. H. Chamberlin, Inc. v. Andrews,34 he dissented from Chief Judge Frederick E. Crane’s majority opinion upholding the constitutionality of New York’s unemployment insurance statute. The statute required employers to pay an amount equivalent to 3% of their payroll — of those employees entitled to benefits — into an unemployment insurance fund to be used to pay benefits. The statute excluded from its coverage employers with less than four employees, farm labor, employment of one’s spouse or minor children, and employment in certain charities.35 Judge Hubbs thought the statute unconstitutional:

[t]he burden is placed not upon industry but on those of a certain class who are engaged in industry and upon others not so engaged. It is placed not alone upon those who have unemployed wage earners but also upon those who have no unemployed workers. No one questions the obligation and duty of the state. That question is not involved. The question here involved is whether the state may place that burden upon a certain class of individuals and corporations for the benefit of another class for whose condition they are in no way responsible.36

The United States Supreme Court affirmed Chief Judge Crane’s majority opinion in a rare four-to-four decision.

In Busch Jewelry Co. v. United Retail Empls. Union, Local 830,37 unions struck against companies, establishing picket lines at the companies’ stores and encouraging picketers to engage in unlawful conduct. In 1935, the Legislature enacted section 876-a of the Civil Practice Act, permitting a court to enjoin only unlawful acts in labor disputes. In upholding Special Term’s injunction, Judge Hubbs concluded that

[t]he effect of that statute is to prevent courts from enjoining peaceful picketing. It was never intended to deprive the Supreme Court of jurisdiction to enjoin dangerous, illegal acts which constituted disorderly conduct and breach of the peace. If such was its intent and effect it is to that extent unconstitutional and void as an attempt to abridge the jurisdiction of the Supreme Court, guaranteed by article VI, section 1, of the State Constitution.38

Judge Hubbs also wrote for the Court in Tierney v. Cohen.39 In 1934, the Legislature enacted article 14-A of the General Municipal Law. The article authorized a municipality to adopt a local law establishing “an electric lighting plant and public utility services.”40 “Local Law 25” purported to create an “authority” to establish, construct, and operate a public electrical power plant. Bonds issued by the authority were supposed to finance the $45 million cost of the project. According to the local law, New York City’s credit did not need to be pledged, and the city was not liable for any deficits of the plant. Special Term determined that Local Law 25 was void, and prohibited the Board of Elections from submitting it to New York City electors. In affirming, Judge Hubbs concluded that

“[t]o decide otherwise would change the whole system of municipal financing and authorize the city to build an electric lighting plant from the proceeds of bonds issued by an ‘authority’ upon its own credit and not upon the credit of the city itself, in direct violation of section 20, subdivision 5, of the General City Law and in violation of section 362 of the enabling act.”41

Reacting to Judge Hubbs’s opinion, New York’s Mayor Fiorello LaGuardia commented that

[t]he way is now open for a clarification of the law — a law to be written for the interests of the city and consumers and not for the utility companies. The decision deprives the utility companies of their hypocritical stand. They cannot now oppose referendums to the voters on the ground that a public plant impairs the credit of the city and adds a burden to the taxpayers, as they did in Auburn; or go to the courts, as they did in New York City, and oppose the plan because it does not pledge the city’s credit and because it is not a risk to the taxpayers. We have them cornered now.42

Judge Hubbs retired from the Court on December 31, 1939, at age 69. Governor Thomas E. Dewey later remarked that Judge Hubbs was “a leading factor in shaping the judicial policies of this State.”43 At his retirement, he was feted to hosts of accolades and tributes, returning to Pulaski, where he was associated with attorney Merritt A. Switzer. He suffered a stroke in April 1952 and at age 81 died on July 23, 1952.

The raw biographical data give a small clue as to what Judge Hubbs was really like. Personally, he was, at a minimum, thoughtful and polite. His considerable editorial and bar support, suggest no less. Choruses of lawyers and newspapers cheered his advancements, proclaiming him a model judge.

Fortunately, we have his granddaughter Joan Morrison to fill out the human side. He was an “avid and skilled fisherman” and spent summers “coddling” his beautiful rose garden knowing the name and age of every flower. He was a family “organizer” who loved to cook at picnics, using egg shells in the coffee grounds, which, he held, “made the best coffee.” Many Sundays were molasses/toffee days using butter and more butter to pull the candy. For him, sewing a button on his shirt was no problem; he could thread the needle easily even in his advanced years. He would say how pleased he was to have played a role in keeping the court house in Pulaski, one of the two shires in Oswego County. He delighted in his family, his wife of 59 years of marriage, and his four great grandchildren (at present expanded to eleven great-great grandchildren). Joan Morrison knows that by reputation he was an outstanding judge. Personally, she knows him to have been an outstanding grandfather.

Progeny

Irving and Nancy Hubbs had two daughters, Florence and Marion. Florence Hubbs married Harold White, and Marion Hubbs married David Graham.

Florence White had one daughter, Nancy McIntosh of Cullowhee, North Carolina, who has two children, Lynn, who resides in Indiana, and Gail of Greenville, North Carolina. Lynn has one daughter, Nancy Lane, who has two children, Eleanor and Jordan. Gail has one son, Steven Blake Poteat.

Marion Graham had two daughters, Joan and Nancy. Joan, who lives in Oswego, NY, married Clark Morrison, III, and has four children, Clark Morrison, IV of Oswego; Nancy Morrison Cysk of Baldwinsville, NY; Graham M. Morrison of Carpentersville, Illinois; and David J. Morrison of Eagle, Colorado. From these four children, Joan has six grandchildren (great-grandchildren of Judge and Mrs. Hubbs): Collin Morrison, Christopher Zysk, Katelyn Morrison, Lauren Morrison, Carlee Morrison, and Johnathan Morrison. Nancy Graham Schneider has three children, Donald Bearden, Anne Bearden Simonson, and James Bearden. Donald Bearden has three children, Maura, Allysa, and Rees. James Bearden has a daughter, Julia Rose.

*Alienation of affections is a “tort claim for willful or malicious interference with a marriage by a third party without justification or excuse” (Black’s Law Dictionary 80 [8th ed 2004]). Criminal conversation is a “tort action for adultery, brought by a husband against a third party who engaged in sexual intercourse with his wife” (id. at 402). For an extended discussion of these torts, in a decision that brought some gender equality to the field, see Oppenheim v. Kridel (236 NY 156 [1923]).

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Churchill’s Landmarks of Oswego County, Family Sketches, pp. 294-295.

Cornell Univ. Record.

Eminent Members of the Bench and Bar of New York, San Francisco, C.W. Taylor, Jr., 1943, p. 267.

Grip’s Historical Souvenir of Pulaski, Historical Souvenir Series No. 13, 1902, pp. 25-26.

In Memoriam, 306 NY vii (1954).

Ithaca Journal-News, Jan. n.d., 1923.

Ithaca (newspaper no name), Dec. 1, 1939 (retirement).

Marston, H.I., Salmon River Odyssey, Pulaski Historical Assoc. (2002), pp. 63-64.

Obituary (George L. Hubbs), Syracuse Post-Standard, Jan. 21, 1922; Oswego Daily Times, Jan. 21, 1922.

Obituary, New York Herald-Tribune, July 23, 1952.

Pulaski Democrat, Jan. n.d., 1893 (Hubbs-Dixson wedding).

Remarks on Retirement, 282 NY v (1939).

Rochester Times-Union, Dec. 26, 1939 (retirement).

Scrapbook of Judge Hubbs, in the possession of his granddaughter, Mrs. Joan Morrison of Oswego, to whom your editor is indebted for sharing it with us.

Syracuse Post-Standard, Jan. 29, 1929.

Endnotes

- 274 NY 22, 26 (1937).

- New York Times, Nov. 7, 1911, p. 2.

- New York Times, Nov. 18, 1911, p. 8.

- Rochester newspaper, n.d. 1916, in Judge Hubbs’ scrapbook.

- Rochester newspaper, Feb. n.d., 1916.

- Oswego Palladium, Feb. 19, 1916.

- Utica Daily Press, Mar. 1, 1916; Utica Observer March 1, 1916; Oswego Palladium, Mar. 6, 1916.

- Oswego Daily Times, May 9, 1918; Fulton Patriot, May 15, 1918.

- We have only the editorial and do not know whether Judge Hubbs endorsed either of the presidential candidates Warren G. Harding or James M. Cox. In those days, Judges were unrestricted in political activities.

- Oswego Palladium, Jan. 15, 1923; Pulaski Democrat, quoting the Rochester Democrat and Chronicle, Jan. n.d., 1923; Syracuse Post-Standard, Jan. 3, 1923; Daily Record (no city) Jan. 3, 1923; Rochester Chronicle, Jan. n.d., 1923; Syracuse Journal, Sept. 29, 1925; Oswego Palladium, July 20, 1925; Syracuse Herald, July 5, 1925; Syracuse Herald, July 7, 1925; Syracuse Journal, Sept. 4, 1925; Syracuse Post-Standard, Sept. 24, 1925; Utica Press, Sept. 24, 1925.

- New York Times, Feb. 26, 1928, p. 2.

- New York Times, Sept. 28, 1928, p. 1.

- New York Times, Nov. 7, 1928, p. 1.

- New York Times, Nov. 9, 1928, p. 1.

- New York Times, Dec. 2, 1928, p. 56.

- New York Times, Nov. 18, 1928, p. 12.

- 263 NY 79 (1933).

- See Braley, What is Good Faith and Fair Dealing? A Lost Chance to Create a Useable Standard Results in an Erroneous Outcome: High Plains Genetics Research, Inc. v. JK Mill-Iron Ranch, 41 SD L Rev 195, 200-201 (1995-1996).

- Kirke, 263 NY at 83.

- Id. at 85 (citation omitted).

- Id. at 90.

- 254 NY 443 (1930).

- Id. at 449.

- 272 NY 268 (1936), rearg denied 273 NY 528, appeal dismissed 301 US 667, reh denied 302 US 774.

- Id. at 274-275.

- 274 NY 22 (1937), appeal dismissed and cert denied 302 US 641.

- Id. at 26.

- 269 NY 291 (1936).

- Id. at 295.

- Id.

- 253 NY 124 (1930).

- Id. at 127-128.

- Id. at 128.

- 271 NY 1 (1936), affd 299 US 515, reh denied 301 US 714.

- See id. at 10.

- Id. at 25-26 (Hubbs, J., dissenting).

- 281 NY 150 (1939).

- Id. at 156 (citations omitted).

- 268 NY 464 (1935).

- Id. at 468.

- Id. at 472-473.

- Court of Appeals Bars Referendum on Power Project, New York Times, October 23, 1935, p. 2.

- Obituary, New York Herald Tribune, July 23, 1952.