This blog article was written by Karen Lin. Karen joined the New York State courts in 1999 as a law clerk in New York County Supreme Court, Civil Division. She is a former New York City Housing Court judge and currently serves as a court attorney referee in Kings County Surrogate’s Court. She is co-chair of the Pro Bono and Community Service Committee of the Asian American Bar Association of New York.

Editor’s Note: Opinions contained in this blog article are those of the author, and do not express any opinions or policies of the Historical Society of the New York Courts.

In honor of Asian Pacific Islander American Heritage Month, I am so pleased that the Historical Society of the New York Courts is recognizing the diversity of our state and its people by celebrating the history, achievements, and challenges of diverse Americans.

The month of May was designated by Congress as Asian Pacific Islander American Heritage Month to coincide with two milestones in American history: the arrival in the United States of the first Japanese immigrants in May 7, 1843, and contributions of Chinese workers to the building of the transcontinental railroad, completed May 10, 1869. But even before them, the first Asians to arrive in North America were Filipino sailors in the late 1500s. Some settled in Louisiana in 1763, working as shrimp fishermen and who would later serve under General Jackson in the War of 1812. The first significant wave of immigration from Korea started on January 13, 1903, when a shipload of Korean immigrants arrived in Hawaii to work on pineapple and sugar plantations. South Asians were noted to have been in the United States since the 1700s and 1800s, from the regions of Punjab and Bengal. Starting in the 1970s, Southeast Asian refugees resettled in the United States from Vietnam, Cambodia, and Laos, fleeing the trauma of war and violence following the Khmer Rouge genocide, mass bombings in Laos, and the Vietnam War. Asian Americans are now the fastest growing major racial or ethnic group in the United States, numbering 22.6 million in 2018.

The term “Asian American” was coined in 1968 by two University of California, Berkeley, students who created the Asian American Political Alliance to unite Chinese, Japanese, and Filipino Americans on campus. The United States Census first used the term Asian and Pacific Islander in 1980 to identify individuals whose predecessors immigrated from more than 20 distinct countries. The moniker became the preferred alternative to the pejorative “Oriental,” a term that geographically referenced Asia relative to Europe and invoked stereotypes of Asians as both exotic and “yellow peril.” It was not until 2016 that the outdated term was eliminated from all federal laws, in a unanimous bill passed in both houses of Congress and signed into law by President Obama.

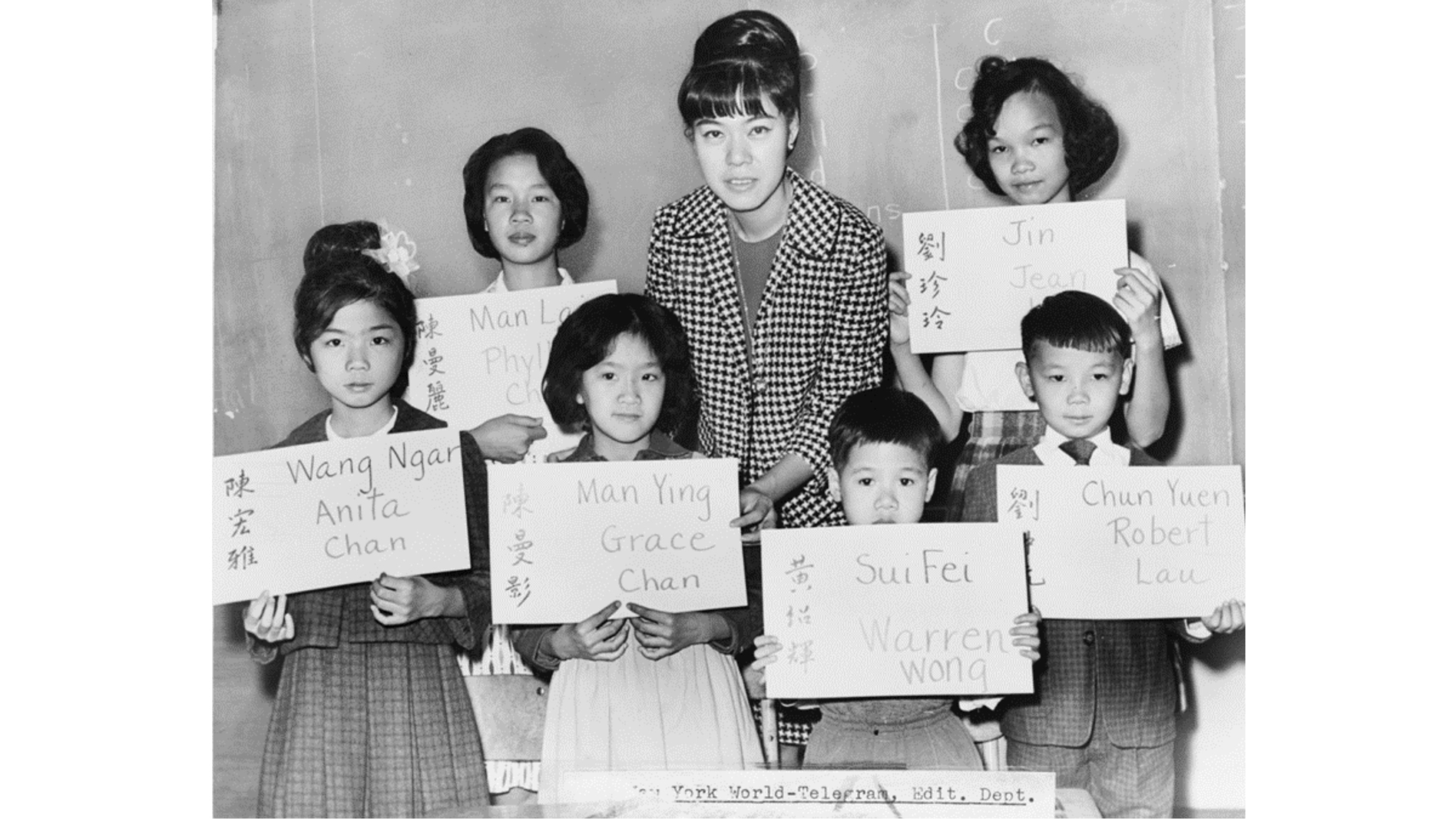

Although grouped together, Asian Americans are in many ways more different than they are alike. Differences exist among Asian Americans in ethnicity, immigration history, religion, language, culture, class, and color. Some, like myself, are part of the first generation who immigrated as children with their skilled or educated parents from countries like Taiwan after the Chinese Exclusion Act was repealed in 1965. Others may be the ninth generation in their family to be born in America. Still others are recent arrivals who face language and cultural barriers, trauma, lack of job skills and need of educational assistance. While being Chinese from Beijing is vastly different from being Chinese American from Buffalo, the distinction is lost when questions about where Asian Americans are really from and astonishment at English fluency reveal hidden beliefs of who is an American.

Asian Americans are often grouped together as an undifferentiated mass and many share the experience of being treated as perpetual foreigners who do not fully belong in America. Consequently, they have not always enjoyed the equal protection of our laws. Asian Americans have been vilified throughout history as the face of threat during times of war, economic distress, and health crises. When the bubonic plague arrived in 1900, the San Francisco Health Department quarantined that city’s Chinatown with barbed wire and ropes. Non-Asian citizens were allowed to leave, but 30,000 Chinese Americans were segregated, confined, and portrayed in the media as dirty carriers of disease.

In 1942, after Japan attacked Pearl Harbor, President Franklin D. Roosevelt issued an executive order that the military used to remove all people of Japanese ancestry, whether American citizens or not, from the West Coast. 120,000 Japanese Americans were forcibly imprisoned in internment camps because of a baseless perception of disloyalty grounded in racial stereotypes, later proven to be without cause. Notably, internment of Americans of German or Italian descent during World War II was not done in the same numbers.

During the early 1980s, the American economy was suffering through a deep recession; unemployment was at its highest rate since World War II, and hostility towards Japanese cars as symbols of foreign encroachment turned into resentment towards Asian Americans regardless of ethnicity or citizenship. In 1982, Chinese American Vincent Chin was beaten to death in Detroit by two unemployed autoworkers who believed he was Japanese and blamed him for the American auto industry’s decline. I remember my father always drove a Ford or General Motors vehicle, believing that his car choice could signal that we were American, a loyalty that would shield us from harm.

The Vincent Chin case increased awareness of anti-Asian violence in America, raising the question of societal responsibility for his death due to the high level of anti-Asian rhetoric promulgated by American auto manufacturers, as well as broadened the application of federal civil rights laws to protect more people.

In this current climate of fear and economic uncertainty precipitated by the COVID-19 global health crisis, xenophobic and racially motivated incidents have spread against Asian American women, men, children, and senior citizens in New York and throughout the country as use of the racialized term “Chinese virus” has stigmatized Americans of Chinese ancestry and targeted Asian Americans as the cause of the pandemic. Since mid March, more than1,700 firsthand accounts have been reported in 45 states of incidents of verbal assaults, racial slurs, workplace discrimination, refusal of service, shunning, spitting, and physical assault. While federal and local law enforcement, the court system, and hate crimes task forces are available to assist victims of violence, we can build bridges of support for one another as fellow New Yorkers to make this next chapter in Asian American history, in our shared American history, one in which we can be proud.

Comments · 1

Comments are closed.