Editor’s Note: Whether or not New York State should have a new constitutional convention is on the voting ballot this November. As such, the Historical Society took a look back on the history of the State’s Constitution with the April 18, 2017 program Constitutional Conventions in New York: Past, Present, and Future. In this article, Professor Peter J. Galie, who opened the program with his lecture “New York State Constitutional Conventions: Back to the Future,” and writing partner Christopher Bopst revisit the Constitutional Convention of 1938.

An expanded version of this article first appeared in New York Archives Magazine, Peter J. Galie and Christopher Bopst, Summer 2017, Volume 17, Number 1, pp. 24-27. New York State Archives: archives.nysed.gov | Archives Partnership Trust: nysarchivestrust.org | New York Archives Magazine: nysarchivestrust.org/magazine/archivesmag_about

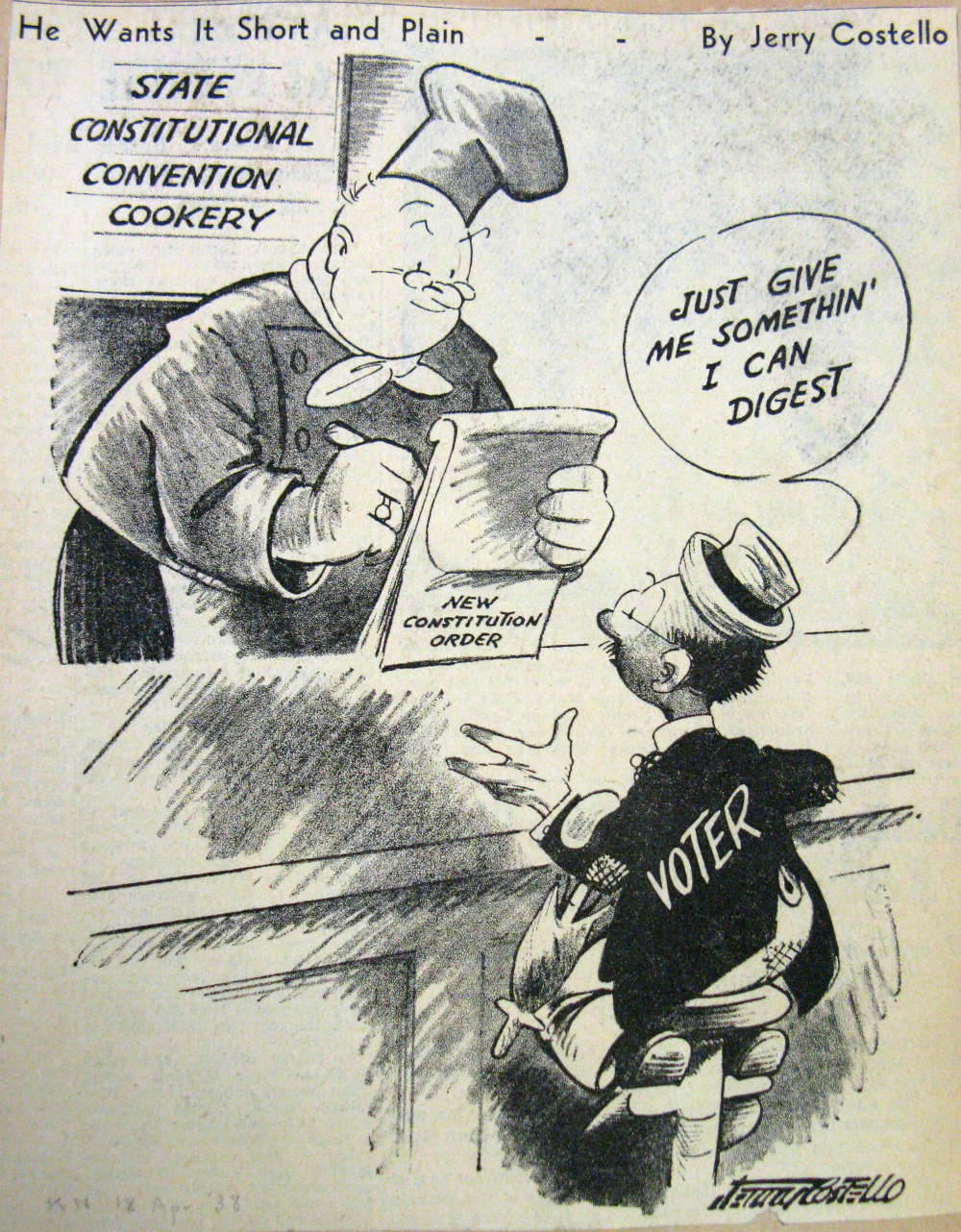

Image: “He Wants It Short and Plain” by Jerry Costello. Archives: L0096-78 Newspaper clippings file 1938.

Secretary of State Edward Flynn called the convention to order on April 5, 1938, amid inauspicious economic and political developments. The country was in the midst of an economic downturn that had started in May 1937. Unemployment, which had declined significantly after 1933, had increased to around 20 percent. The number of democracies throughout the world had fallen to pre-World War I levels.

The previous debate over the call for a convention was notable for the absence of issues that might have provided an agenda. But Flynn’s opening remarks sounded the note that would provide the convention with a theme and purpose:

You are assembled during a most critical time in the world’s history, when new forms of government are being created throughout the world and democratic principles are being forgotten.

The constitutional convention held in New York State in 1938, the state’s ninth, was a “people’s convention.” The convention was called pursuant to the provision of the state constitution mandating that every twenty years citizens be asked whether they wish to convene a convention to revise and amend the constitution. It was a people’s convention in another sense: Neither major party addressed the question in their respective platforms.

Voters approved the convention by a margin of 1,413,604 to 1,190,275. Discouraging for those who valued the exercise in popular sovereignty provided by the automatic call provision was the startlingly large number of voters who ignored the proposition. The total vote on the convention question was three million less than that cast in the governor’s race on the same ballot.

As they did in the 1894 and 1915 conventions, Republicans captured a majority of the delegates. Prominent delegates included Frederick E. Crane, Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals (who was later elected convention president); four-time governor Alfred E. Smith; U.S. Senator Robert F. Wagner; Congressman Hamilton Fish Jr.; and urban planner and power broker, Robert Moses.

The Republican Vision and the Global Crisis

No amount of preparatory material could prepare delegates for the unique role the 1938 convention would play in New York’s constitutional history. Recognizing that Fascism and Communism had attracted millions throughout the world, including many in this country who were having doubts about the ability of our political and economic institutions to meet the challenges of the modern world, President Crane’s opening address put the work of the convention in a global context. “We are here to do one thing, if nothing else: To prove to the world that our form of government does work; that it will work efficiently, and can meet the problems of the day and the necessities of the times as well and as intelligently as any other form of government.”

What did the convention need to accomplish to “prove” that case? Crane emphasized the need to reaffirm and expand, if necessary, the traditional political values that were under attack from both the left and the right: freedom of speech, freedom of religious worship, freedom of the press, a free and independent judiciary, and electoral freedom. However, Crane believed this reaffirmation would not require major changes. “There has always been one fundamental principle for the guidance of bodies like this, which I am sure you will bear in mind: That is, that there is no value in change just for the sake of change.”

The Democratic Response

On April 18, Senator Wagner, a leading figure in fashioning Roosevelt’s New Deal, offered an alternative vision of the convention’s role. After reaffirming Crane’s commitment to traditional values, Wagner went further:

… this Convention will not prove that democracy can work merely by strengthening the traditional protection of the Bill of Rights, important as that protection is. The furtherance of human freedom requires more in our time than the prevention of official tyranny. The problem of the day is to meet the threat to freedom that comes from another source — from poverty and insecurity, from sickness and the slum, from social and economic conditions in which human beings cannot be free. This threat to freedom can only be met by affirmative action, much of which must come from the State. The need for such affirmative action has been fully recognized in New York.

Fundamental Principles

The Republican vision concentrated on changes to the Bill of Rights. The delegates adopted a provision prohibiting discrimination against an individual’s civil rights based on race, color or creed. It was the first appearance of an equal protection clause in the New York Constitution.

Protection against unreasonable searches and seizures, previously provided in the statutory laws of New York, was given a home in the constitution. Intense and lengthy debate focused on whether to adopt an exclusionary rule prohibiting the use of any evidence obtained by an illegal search or seizure. It was one of the most enlightening and high-quality discussions of civil liberties in the annals of New York’s constitutional history.

The importance of this issue was underscored when, in response to an invitation to address the convention, Governor Herbert H. Lehman sent a message that was read into the record. It was a stirring defense of the search and seizure provision and the exclusionary rule. Situating his defense in the context of the global threats to constitutional democracies, Lehman wrote:

In these crucial days when democracy is challenged in many parts of the world and when we have a compelling duty and privilege to preserve democracy against the assault of both Communism and Fascism, I am of the firm conviction that the Constitutional Convention … has no more important task before it than that of strengthening the Bill of Rights.

On June 14, opponents of the exclusionary rule read into the record a speech given by Thomas E. Dewey a few days earlier at Cooperstown vigorously opposing the rule. Dewey, the district attorney for New York County (and subsequent three-term governor), had a growing reputation as an aggressive prosecutor of organized crime. After referencing specific crimes that would not have been solved had an exclusionary rule existed, he concluded:

It will protect no one except the guilty criminal. It is designed for the exclusive purpose of depriving the people of this State of evidence of crime. No innocent citizen, no law-abiding person, can benefit by the suppression of evidence, however obtained. The proposal will have the single effect of protecting murderers, gangsters and kidnapers.

It did not go unnoticed that the debate pitted Governor Lehman against his most likely opponent in the gubernatorial election later that year. Dewey’s arguments prevailed. The convention did not adopt an exclusionary rule, but Lehman defeated Dewey in the November election.

The Positive State

If there was one consistent theme that emerged from the convention it was the willingness of delegates from both parties to recognize the role of the government in providing for the social and economic welfare of its citizens. Two new articles — Social Welfare (Article XVII) and Housing (Article XVIII) — were added, including a mandate that “aid, care and support of the needy … shall be provided by the state and by such of its subdivisions.” The boldest innovation to the Bill of Rights was the addition of a “Labor Bill of Rights,” which provided that labor was not to be considered a commodity or an article of commerce, limited hours of labor on public works, and guaranteed the right to organize and bargain collectively.

This consensus on government responsibility for the social and economic welfare of its inhabitants was in sharp contrast to the work of prior conventions, which had been virtually mute on such issues. The commitment to a new set of social responsibilities produced a New York Constitution that was more progressive than either the national Constitution or the decisions of the U.S. Supreme Court. The document gave constitutional status to a political theory that recognized an active role for the government in providing for a variety of welfare programs for those in need. Its guiding spirit, sometimes described as “positive state” or welfare state liberalism, marked a turning point in our state’s constitutional history.

In fusing the visions of Chief Judge Crane and Senator Wagner, it is fair to say, the convention did “prove to the world” that our form of government works.

About Peter J. Galie

Peter J. Galie is the Professor Emeritus at Canisius College in Buffalo, New York and earned his Ph.D. from the University of Pittsburgh. He is the author of numerous articles in the area of state constitutional law and three books: Ordered Liberty: A Constitutional History of New York (Fordham University Press, 1996); The New York Constitution: A Commentary, with Christopher Bopst, 2nd ed. (Oxford University Press, 2012); and co-editor with Christopher Bopst and Gerald Benjamin, New York’s Broken Constitution: The Crisis in State Government and the Path to Renewed Greatness (SUNY Press, 2016). He is currently serving on a Task Force on the Judiciary Article of the State Constitution formed by Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Janet DiFiore.

About Christopher Bopst

Christopher Bopst is the Chief Legal and Financial Officer at Sam-Son Logistics in Buffalo, New York. Before that, he was a constitutional litigation partner at law firms in New York and Florida. He is the co-author with Professor Peter Galie of the leading reference work on New York’s State Constitution, The New York Constitution (Oxford University Press, 2012), as well as numerous articles on the state constitution. He is also a contributor to and co-editor (with Professor Galie and Professor Gerald Benjamin) of a volume of essays entitled New York’s Broken Constitution: The Governance Crisis and the Path to Renewed Greatness (SUNY Press, forthcoming 2016). In 2016 he was appointed to a Judicial Task Force on the New York Constitution formed to advise the Chief Judge and the New York Court System on issues related to the upcoming vote in 2017 on the holding of a constitutional convention.