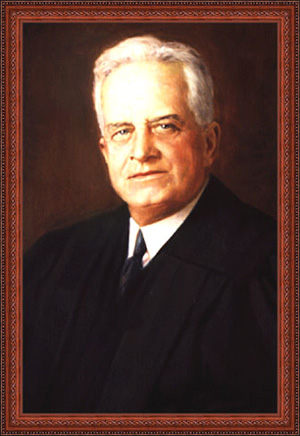

Edward Ridley Finch was born in New York City, November 15, 1873, son of Edward Lucius and Anne Ridley (Crane) Finch and a descendant of Abraham Finch, a native of England, who came to America with John Withrop’s company in 1630 and settled in Massachusetts.

Judge Finch received his preparatory education at private schools and was graduated B.A. at Yale College in 1885, with special honors in political science and law. He graduated from the law school of Columbia University with an LL.B. in 1898. Admitted in that year to the New York State Bar, he began practice in New York City with the law firm of Kenneson (Thaddeus D.), Crain (Thomas C.T.) & Alling (Asa A.). Later he was a member of the firm of Tappan & Finch, with John B. Coles Tappan, and then formed a partnership with John Burlinson Coleman under the name of Finch & Coleman.

On August 20, 1915, he was appointed Justice of the New York Supreme Court by Gov. Charles S. Whitman to fill the unexpired term of Justice John J. Delancy and in the following November was elected for a term of fourteen years, being nominated by all parties. In 1922, Governor Nathan L. Miller appointed him associate justice of the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, First Department. He was re-designated to the Appellate Division in 1927 by Gov. Alfred E. Smith, and as the nominee of all parties, was unanimously re-elected to the Supreme Court in 1929. In January 1930, Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt re-designated him an Associate Justice of the Appellate Division, and in April 1931 Governor Roosevelt designated him as Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, First Department. In 1934 he was elected a Judge of the Court of Appeals for the term expiring in 1948. He resigned April 30, 1943 and resumed the practice of law in New York City, as Finch & Schaefler.

During his career on the bench, Judge Finch has rendered a number of important opinions. He wrote the unanimous decision of the Appellate Division in the Matter of the City of New York v. Manhattan Railway Co. (229 A.D. 617), involving the compensation to be paid in condemnation for the removal of a portion of the Third Avenue elevated railroad; also in the case of People ex rel Pineus v. Adams (274 N.Y. 447), upholding the constitutionality of the statute providing for joinder in one indictment of several connected crimes. He wrote the dissenting opinion, later sustained by the Supreme Court of the United States, holding unconstitutional the statute involved in Mayflower Farms, Inc. v. Baldwin (267 N.Y. 9).

During 1901-04 Judge Finch served in the State Assembly, and as a member of that body, was the author of the law placing on the preferred list for jury service those who fail to register and vote; the law known as “the signature law,” a notable ballot reform measure, and laws designed to protect the labor of women and children. Deeply interested in the protection of children, he was the founder in 1904 of the National Child Welfare Committee. He was closely identified with educational laws and movements and was the author of several measures affecting the government, child welfare and ballot reform.

He was a supporter of strong judicial use of summary judgment and of judicial award of attorney fees and disbursements, and judicial penalties, using both against attorneys and clients bringing unmeritorious or frivolous cases. By appointment of President Harding, he served as envoy extraordinary and minister plenipotentiary on a special mission to Brazil, headed by Secretary of State Hughes, to celebrate the Brazilian centennial in 1922. He was decorated chevalier of the Legion of Honor of France in 1929 and commandatore of the Order of the Crown of Italy in 1932, and was awarded the Columbia University medal in 1933 “for conspicuous alumni service.” The degree of LL.D. was conferred on him by St. Stephen’s College, Annandale, N.Y., in 1928, Columbia University in 1929 and New York University in 1935. Judge Finch was a founder of the Honest Ballot Association, a Trustee of the Cathedral of St. John the Divine and the Northern Dispensary and a member of the American and New York State Bar Associations, Association of the Bar of the City of New York, New York County Lawyers’ Association, American Law Institute, Metropolitan Museum of Art, St. Nicholas Society (President, 1931-1933), Sons of the American Revolution, New England Society, New York Society of the Order of Founders and Patriots of America, The Pilgrims of the United States, Alumni Association of the Law School of Columbia University (President, 1922-1924), Phi Beta Kappa Society (President, 1929-1930), the University, Union, City, Republican, Downtown, Yale, Church, Union League and Manhattan clubs, of New York City; Ft. Orange (Albany) Club; and the National and Oakland Golf Clubs, of Long Island, N.Y. An Episcopalian in religion, he was lay delegate from New York to the triennial general convention of his Church in 1934.

Judge Finch died on September 15, 1965, and is interred in the Finch mausoleum at Woodlawn Cemetery.

Judge Finch’s judicial life is best exemplified by a 1932 Columbia University Law School Speech on Judicial Improvement in his own words as follows:

I feel very much like the visitor to the lecture on the classification of the books of the Old Testament.” After a long lecture, the speaker turned to the audience and said, “And now what place shall we give to the prophet, Hosea?”, whereupon a man in the back of the hall said, “Do not bother. He can have my place.” That reminds me that a great president of a large university said to a friend of his the other day, “What was the name of the man who invented cotton gin?” to which the reply was, “I have tried all kinds of gin these last few years and I think each one was worse than the last. I am not interested in cotton gin and I do not want to know the name of its inventor.

But seriously, we started out to demonstrate that the loyalty of the alumni to a graduate school can be as great, if not greater, and its spirit as fine, if not finer, than the loyalty and spirit of an undergraduate college. It seemed then and it seems now as if the graduates of the Columbia Law School can really find scholarship interest and a deeper and finer basis of association than is possible among the graduates of an undergraduate college. Since this association is now the largest association of its kind that I have been able to find in the English-speaking world, it seems to me that this association might well take on, on behalf of the profession and its brethren in the profession, such plan for the betterment of the practice of the law as come to hand as the next step in improvement. I believe there is much that an Association such as this can accomplish for the benefit of the profession as a whole and for the benefit of its own members and their clients. As an example, I picked up a record on appeal the other day and out of 48 pages, 17 of them were devoted to the printed repetition of titles. It would be perfectly possible for such an Association as this to point the way to have those 17 pages of repetition of titles condensed into 17 lines or less. In other words, instead of reprinting the title and taking up one-half of the folio in doing it, three words, ‘See title folio’ could simply take its place. The same applies also to other repetitions in the printing of cases on appeal.

Then, too, there is the wastage of the time of jurors who are summoned to all Courts. There could be a common jury room from which the jurors could be summoned to the Part where they were desired and in the meantime, they could be made comfortable so that they could do such writing and telephoning as was necessary.

Then, too, there seems to me to be much waste in acquainting different judges with the facts involved in the same case. Why would it not be possible to have the cases assigned in rotation to the judges so that when one judge became acquainted with the case, all subsequent matter in that cause would have the benefit of such acquaintance? Some of these matters, such as the repetition in printing of cases on appeal, are very simple and the change would be brought about easily and it would be of immediate benefit to every practicing lawyer, because each item of cost which the lawyer has to pay out on behalf of the client, from the client’s point of view, is just as much a part of the cost of litigation as any other portion. Some of you may say, “Why don’t the judges adopt plans to carry out these proposals or other proposals that may be better?” The answer is that the judges really carry out the reasonable demands that are made on behalf of the Bar.

I think we have all noticed with alarm the growing antagonism between the Government and the individual citizen. It seems as if the Government was seeking its advantage as against the individual citizen and the citizen on the other hand tries to protect himself as against the Government. In other words, instead of free cooperation, there is a somewhat bitter antagonism. I believe that this Association can do much to emphasize the importance of mutual care on the part of the Government for the best welfare of its citizens and on the part of the citizen for the best welfare of the Government. There must be mutual responsibility for the welfare of each. In the New England town, such mutual carefulness and responsibility were obvious and apparent to everyone but with the great growth of the Government, this mutual relationship of the citizen to the Government has somewhat disappeared. It is not due to any one cause. Perhaps the practical workings of the income tax have had as much to do with it as any other. Then, too, in a great city, the neighborliness that we know in the country is apt to disappear. We can revive that neighborliness. We can find the familiar traits that we like in one another and overlook those we do not like.

The world of realism and practicality in the New York Courts and the judiciary is truly exemplified by these above words of Judge Finch spoken many decades before today’s great emphasis in the media on therapy, practicality and realism.

Progeny

On January 8, 1913, at Riverdale-on-Hudson, N.Y., Judge Finch married Mary Livingston, daughter of Maturin Livingston Delafield, a West Indian merchant, of New York City, and they had three children: Mary Delafield Noelle, who married Col. Francis Waller Haskell; Anne Crane Finch, who married Howard E. Cox (their son, Edward Finch Cox, is an attorney in New York); and Ambassador Edward Ridley Finch, Jr. who married Pauline Swayze Finch. Ambassador Finch lives in New York and has three children: Dr. Elizabeth Finch Coe of Bethesda, Maryland; Edward R. (Ted) Finch, III and Dr. Maturin D. Finch, both of Lexington, Massachusetts.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Armstrong, Summary Judgements in Illinois, 20 Chi-Kent L. Rev. 215, 225 (1942).

Current Events, 9 ABAJ 599 (1923).

Finch, Judicial Politics: A Tribute to Edward R. Finch (1966). Written by the author of the foregoing biography, it is a compendium of Judge Finch’s public life, and includes news articles, letters, and other materials.

“Judge Edward R. Finch Law Day Speech Awards Guidelines,” A.B.A. Awards & Contests, at http://www.abanet.org/publiced/lawday/finch/guidelines.html (last visited July 26, 2005).

Morgan & Maguire, Looking Backward and Forward at Evidence, 50 Harv. L. Rev. 909, 934 (1937).

“National Conference on Judicial Councils,” 17 B. Br. 144 (1941).

Notes, 23 Colum. L. Rev. 465 (1923).

Nygaard, A Bill of Rights for the Twenty-First Century, 21 Hastings Const. L.Q. 189, 189 (1993).

Praksher, Comment, The Proposed Civil Practice Law and Practice Rules, 8 St. John’s L. Rev. 233, 233 (1934).

Shientag, Summary Judgment, 4 Fordham L. Rev. 186, 187 (1935).

Vanderbilt, Administration of JusticeCThe Courts and Law Reform, 1943 Ann. Surv. Am. L. 908, 923 (1943).

Published Writings

Book Review, Milville Weston Fuller: Chief Justice of the United States, 1888-1910. By Willard L. King, 51 Colum. L. Rev. 142 (1951).

Essay, in Annual Handbook, National Conference of Judicial Councils (1941).

Pre-Trial Procedure, 15 Tenn. L. Rev. 605 (1937).

Speeding Up the Courts, 15 Tenn. L. Rev. 596 (1937).

Book Review, Declaratory Judgments. By Edwin Borchard, 36 Colum. L. Rev. 1378 (1936).

Some Fundamental and Practical Objections to the Preliminary Draft of Rules of Civil Procedure for the District Courts of the United States, 22 A.B.A.J. 809 (1936).

Restatement of the Law of Conflict of Laws as Adopted and Promulgated by the American Law Institute Containing New York Annotations, with Elliott Cheatham and George W. Murray (1935).

A Non-Political Veto Council on Judicial Character and Fitness for Those About to be Nominated or Appointed to the Bench, 20 A.B.A.J. 144 (1934).

Progress in ProcedureCPast, Present and Future, 4 Brook. L. Rev. 1 (1934).

“Extension of the Right of Summary Judgment,” in Raymond Moley & Schuler C. Wallace, eds., The Administration of Justice (1933).

Franklin Delano Roosevelt, the Twenty-Third Lawyer-President, 67 U.S.L. Rev. 138 (1933).

Restatement of the Law of Contracts and Its New York Annotations: A Word of Appreciation, 67 U.S.L. Rev. 180 (1933).

Summary Judgment Procedure, 19 A.B.A.J. 504 (1933).

Summary Judgment Procedure, 17 J. Am. Jud. Soc. 180 (1933).

Extension of the Right of Summary Judgment, N.Y. State. B.A. Bull. (May 1932).

Judicial, in Place of Legislative, Court Procedure, 10 N.Y.U.L.Q. Rev. 360 (1932).

“Unnecessary Expense on Appeal,” Address in 10 Dicta 20 (1932).

Address, reprinted in 49 A.B.A.R. 588, 593 (1924).