This is a revised version of a remembrance of Judge Ostrau by John F. Werner and Robert C. Meade, Jr., Esq. that appeared in the court’s newsletter, Just Us, in 2013, which in turn was based in part on a eulogy that was given by Mr. Werner at the funeral service for Judge Ostrau, who passed away in December 2012.

In 1970, Stanley S. Ostrau was serving as Law Clerk to Justice Edward T. McCaffrey, a Bronx Justice on assign- ment to New York County. First impressions are often lost in time, but more than likely most would have been struck then by Stanley’s appearance, as indeed many were over the years to follow. Stanley was a big man. He was tall and broad-shouldered. The room in chambers then occupied by Judge McCaffrey’s staff (his Law Clerk, Stanley, and his secretary) was small, but appeared all the smaller because Stanley seemed to fill most of it. Stanley would often ease back in his desk chair, stretch out his long legs, prop his shoes on top of the desk, and engage the world. This re- laxed posture gave no hint of the prominence he was later to attain on the bench and in court administration.

Stanley was a person of presence, impossible to overlook in almost any setting. Many might say that he was a great bear of a man, as the saying goes, but, though he might seem gruff on a brief first encounter, or if you knew him only superficially, he was in truth quite the opposite: caring, thoughtful, sincere, canny (in a Bronx sort of way), loyal, and entirely devoted to his family and friends. Stanley also had the most engaging smile and when he was happy – – as he was so often when among his colleagues, court staff, and trial attorneys – – his broad smile would appear, suggesting the happy warrior he was and his love for those around him and for whatever mission he might be on in the courthouse.

Stanley, of course, had been shaped by his parents, Louis and Irene. His mother, for instance, had one particular impact upon him that played out for many years afterward. Irene was a person of considerable character. She was a business woman in the early years of the twentieth century, a time when, it need hardly be said, few women worked outside the home, and she had a serious interest in the stock market, which set her apart even more. Both Stanley and his brother inherited this interest. From time to time Stanley would – – in rather hushed tones and very much as if he were sharing a state secret – – opine on the merits or demerits of one stock or another. Such musings were lost on us, but he tolerated our indifference with benign amusement and never gave up on us entirely. Whatever happened to ParkerVision, anyway?

Stanley grew up in the Bronx and attended De Witt Clinton High School. He served in the European theater during World War II and thereafter attended New York University and its law school. He was very lucky to meet and marry Eleanor Tananbaum, who passed away in 2007, a loss from which it is fair to say Stanley never really recovered. Eleanor was a formidable person in her own right, a Phi Beta Kappa graduate of Cornell, with an M.A. and a Ph.D. in government and political theory. She had a distinguished career in academia, including for many years as a professor at Manhattan College. They were very well matched. They had two daughters, Amy Ostrau and Gail Ostrau Young, and one granddaughter, Saria.

After graduation from law school, Stanley was in private practice. He served for nine years as a trial lawyer in the Tort Division of the Corporation Counsel’s Office, by the end of which time he knew his way around the courtroom almost as well as anyone could. His years trying cases, including in his own firm, grounded his later judicial service; he knew how to try a case, the value of a case, the needs of clients, the needs of attorneys on trial, and the vagaries of professional life, including all of the countless hurdles faced by practitioners who come to court. Much to his credit, Stanley never for- got any of that while on the bench.

He also served for a period as Law Clerk to Justice Alvin Klein, father of one of his successors as Administrative Judge, Justice Sherry Klein Heitler. Life can weave surprising connections.

In 1970, this court was very different from the institution it is today, or as it was during Stan- ley’s tenure as Administrative Judge. There were, for instance, very few women on the bench or the staff. There were only two women Justices, Birdie Amsterdam and Margaret Mary Mangan, there was only one woman in the Law Department, Florence Belsky, and few women Law Clerks, among them the redoubtable Betty Weinberg Ellerin, later a legendary jurist. There has been progress here and Stanley as Administrative Judge contributed to it.

Recalling those days brings to mind that there was a young Law Assistant named Jonathan Lippman who was very much part of Stanley’s circle during those early years, and ever afterward. Stanley was always very proud of Jonathan’s many achievements. Among Stanley’s happiest days was the one he spent in Albany, in the Court of Appeals, attending Jonathan’s investiture as Chief Judge of the State of New York.

Stanley was appointed to the Civil Court in 1973 and was elected to that court the next year. Some years later he became a Supreme Court Justice by Designation and was elected to the court in 1984. His career flourished, he distinguished himself trying cases, and he was called upon increasingly by our Central Administration to assume administrative duties and special assignments. It was not his ambition to do so and he did not campaign for such advancement (if that is what it was), but if he was asked to assume a responsibility, even one not especially attractive – – administration is a truly thankless task – – he would do it if he thought he could be of use. Stanley was a trial lawyer and a trial Judge and he was accordingly practical; what he wished to do was to be of use.

Stanley was devoid of pomposity and arrogance. The key to this is that, despite having grown up during the Great Depression and having served in Europe, Stanley had an essentially sunny – – which is not to say naive – – view of the world. The countless ironies that mark all of our lives were not lost on Stanley, and he confronted them, and challenges of every sort too, with his refined sense of humor and with a ready laugh. He liked to joke and tell stories and often did so. He loved to poke fun at others whom he knew (but never maliciously) and even more so at himself.

Stanley was a passionate golfer. Often he would urge on his colleagues and staff the wisdom of taking up the game, but, if his experience with us is any guide, he was an abject failure as a golf evangelist. He liked to make mischievous remarks. As AJ, he often said that the rumors he liked best were the ones he started himself. One of the truths about being Administrative Judge, he would say, “is that almost every day I have the opportunity to make one person happy and countless others not.” In order to ensure that the County Clerk of New York County, his co-conspirator and close friend, Norman Goodman, received the proper recognition, he would double up on the acknowledgment by greeting him or referring to him publicly thus: “Norman Goodman, Norman Goodman.” It could be that on one occasion Stanley had inadvertently failed to mention Norman’s presence, that the lapse had been duly brought to Stanley’s attention by somebody, and that forever after Stanley was trying to make amends for that unpardonable oversight while making a joke out of it in the process. Stanley would often refer to Norman as “Mr. Foley Square,” sometimes adding that if he, Stanley, sent out thousands of jury summonses every year with his name on each he too would be known as Mr. Foley Square.

At the end of almost every day during his years as AJ, Stanley would hold court in his Chambers in Room 690, and his dutiful servants, including Bob Kantor, Peter Diskint, Jack Jaeger, Frank Byrne, and both of us, would assemble there, or reassemble (since it was likely we had been with him more than once that day since he was very much of a collaborative frame of mind in his approach to administration). We would talk the talk of the court, but invariably the conversation would drift thereafter to other matters of deep interest, including the market, football, golf, or Stanley’s poker nights. Stanley was one great poker player, with a prodigious memory and capacity for numbers, something which his mother’s financial interests had no doubt nurtured in him. There would be many laughs and time would just seem to disappear, and as we would wander out of Stanley’s Chambers late, one of us would often tease Stanley, who did not mind, that thanks to him it was so late there was really no reason for any of us to go home.

We should confess that we were constantly traumatized by Stanley as we followed him across this street or that. We like to think of ourselves as true New Yorkers, but we have our limitations. Stanley, however, had few, at least so far as we could discern. Traffic lights seemed to mean nothing to Stanley, or perhaps to him were merely colorful decorations. Depending upon how much of a hurry he was in, he would amble through the intersection or charge boldly into the street, ignoring red lights and the traffic, evidently confident that no vehicle would be so self-destructive as, nor have the temerity, to run into him. We suppose that if we had frames as large and imposing as Stanley’s, we too would have had such confidence. But we did not, and so we would say to him: “Stanley, what about us?”

There was, however, another side to Stanley, and it was a huge one, and anyone who missed that would have seriously misunderstood him. He cared a great deal about this court, its Justices and staff, and about our common struggle to provide true justice to every citizen. This concern flowed out of who Stanley was as a person. He treated everyone, whether the Chief Judge, an ordinary lawyer, a complaining juror, a Justice or a member of the court staff, with respect and genuine concern. In this he resembled his predecessor, the sainted Xavier Riccobono, though with a different flavor. This attitude was not a cliche or a pious abstraction to Stanley. We know this because we saw the concrete manifestations of it on innumerable occasions over the years we knew him. Stanley was nice to people, no matter who they were.

There were times when Stanley came across persons in difficulty – – colleagues or members of the staff. Quietly, sometimes without the persons even knowing, Stanley went out of his way to help. There are many who are in his debt.

When Stanley was given a job, he made a point of devoting all he had to it. When he became Administrative Judge, he undertook his work without paralyzing trepidation at the size of the shoes he had to fill. Again, he was practical, and there was no point in trying to be a second Judge Riccobono since no one could achieve that. The point was rather to do one’s very best with all one’s energy without worrying how it would come out in the end. The end would take care of itself. So, he set about to do whatever lay in his power to make things run even better than they had been doing.

It is not fully understood by the commercial Bar, but Stanley had a significant role in the creation of the Commercial Division, surely one of the most successful innovations undertaken by the Unified Court System of New York State on the civil side since the establishment of UCS. The first step on the path occurred in 1992, when a small court system committee on which Stanley, then Administrative Judge, served recommended the establishment of experimental Commercial Parts in his court, New York County Supreme Court. These Parts went into operation in January 1993. We well remember sitting in Stanley’s Chambers in late 1992 as he wrestled with the judicial appointments he would recommend for the Commercial Parts; with determining a suitable and reasonable number of commercial cases he would assign to the Division; with putting in place adequate operating procedures; and with devising a methodology so that the Parts could cope with the volume of cases that might come to them thereafter. These last three were knotty technical problems, but Stanley arrived at sound decisions and they have stood the test of time. The Commercial Parts were a great success and they led directly to the formal introduction of the Commercial Division in 1995. It was Stanley who ushered this institution into being in our court.

He introduced ADR in our court, both in the Commercial Division and in the matrimonial field. Our efforts continue today, as we try to do more with less, building upon what he began. Because he was practical and fair-minded and understood so well the trial of cases, Stanley was an outstanding settler himself, and finding ways to promote early settlements and instituting settlement procedures were of deep interest to him.

One of the major challenges Stanley faced as Administrative Judge was improving the functioning of the Individual Assignment System, which had been introduced only a few years before Stanley became AJ in 1991. Where once vast master calendars had prevailed, our court had moved to a system of individually assigned cases. The legal culture of that time had been very greatly improved by the efforts of Judge Riccobono, but was still not perfectly hospitable to the new system, with some resulting inefficiencies that Stanley sought to tackle.

Where, for example, there had previously been a single Matrimonial Motion/Trial Part, to which he himself had been assigned at one point, he introduced a team of Matrimonial Parts. This approach, he felt, would bring more sustained attention to a particularly important and challenging segment of the court’s inventory, where the lives of children are at stake. His view was shared by Hon. Jacqueline W. Silbermann, who later became one of his successors as Administrative Judge and also served as Statewide Administrative Judge for Matrimonial Matters.

The new IAS system generated huge motion calendars weekly in all of the Parts of the court, with which Justices struggled. When a Justice returned from vacation in September, he or she might find 50 or more motions on the Part’s calendar for weeks on end. To reduce these burdens, Stanley introduced the Motion Submission Part Courtroom (Room 130), which shifted from Justices and their immediate staff members to clerks the routine, but time-consuming task of collecting motion papers and processing requests for adjournments while ensuring that motions were not unduly delayed. This innovation benefitted attorneys as well, who could submit their motion papers through clerks or service without the need to come to court. And it freed attorneys from having to keep track of Part numbers, motion days, and motion times for all of the 50 or so Parts in the court in order to be able to make motions returnable properly, and from having to run around to the many Parts in our several facilities in order to submit papers or request an adjournment. The Courtroom continues to function to this day.

During Stanley’s tenure, the court was faced with a fiscal crisis. A number of court Parts had to be closed. Stanley was deeply concerned that the staff of the court not suffer unduly, and although there were some layoffs, Stanley was able to minimize them. The pain felt by the Bar and the public was thus also reduced from what it otherwise might have been.

During this difficult time, the processing of long-form orders became very seriously delayed, by many months. Stanley promoted the policy of including, whenever possible, decretal paragraphs in decisions so there would be no need to settle orders after the issuance of decisions. Prior to that initiative decisions reflexively ended with the words “settle order.” The new policy simplified and expedited proceedings for clients and the Bar, saving them time and money, without adversely affecting the court’s Justices. Stanley saw to it that the new policy was explained in a manual that was distributed widely; a revised edition remains in use today. This was perhaps the first time that the court sought to articulate its internal operations in writing. Before that, a Justice, attorney, or clerk new to the court would have to learn how the court worked by guesswork, trial and error. The new policy proved sufficiently successful that the Central Administration issued a statewide uniform rule based on it. In the years since Stanley introduced this policy, it has greatly improved the processing of decisions and orders. The policy remains very much in effect today.

This court has continued the practices promoted by Stanley of recording its procedures in manuals for Justices and staff and publishing material for the public as well, as is apparent to any visitor to our court’s website: www.nycourts.gov/supctmanh.

It was under Stanley’s leadership that our court first began to develop a comprehensive, court-wide approach to case management. Under the master calendar system, there had been nothing for the court to manage except the issuance of decisions on motions and the scheduling of trials. Cases ran themselves, which is to say that inefficiency and delay were too often realities. To bring effective management to bear, the court experimented with conference Parts and Trial Assignment Parts and developed ways to use reports generated by our computerized case management application to manage individual inventories. The principles that first germinated under Stanley’s direction were passed on to and further developed by his successor, Judge Stephen G. Crane, and also came to be embodied under Judge Crane in a booklet, a revised edition of which continues to be used today.

These are merely some of the challenges with which Stanley grappled as AJ. But Stanley was willing to wear more than one hat if called upon to do so. He did that in 1987, when he served as Surrogate of Bronx County while continuing his judicial duties in this court. While AJ, Stanley also served as Presiding Justice of the Appellate Term, which role he took on in 1986. The work of that court is very important to the social dynamic of New York City. Space does not permit any detailed discussion, but during Stanley’s time there landlord/tenant law was evolving rapidly and dramatically. Here, too, Judge Ostrau’s leadership was a vital force for justice and for progress.

Stanley’s innate cheerfulness, open-mindedness, sense of fairness, and respect for others made him a great leader of this court. The bench of this court in those days embraced a wide array of personalities, more than one or two of them forceful. He got on well with all of his colleagues, even those whom he was occasionally forced to disappoint with an inability to accommodate a request for an assignment or the next chambers available. Stanley’s door was always open to the members of the court’s staff, whom he sought to help whenever it lay in his power to do so. Stanley’s skills kept things harmonious and made him friends. He was gifted in this regard, like his predecessor, Judge Riccobono. Many of us do not play poker, have only a passing interest in football, cannot play golf, and are not even from the Bronx, yet Stanley did not hold these errors in judgment against us and we became close friends.

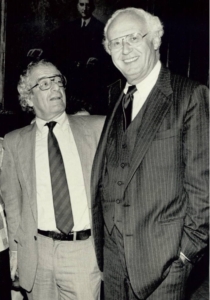

There is a photograph of Stanley taken in May 1991. Stanley is in his element. He is at the lectern in the great rotunda, his colleagues, court staff, and members of the Bar and the public crowded all around him and even on the balcony. This was the celebration of a truly momentous occasion in the life of this institution – – the 300th anniversary of the establishment of this court. This photo records a great event, but it is also a reminder of an enduring truth, one that is so important that we have had occasion to note it in other contexts, a truth that, because we are all so busy every day with so many important things, we may give short shrift: all of us in this court stand on the shoulders of those who have gone before. And all of us here today, therefore, whether we had the privilege of knowing Stanley or not, stand on his broad shoulders. Stanley, as we say, was a big man, and he was so in more ways than one. Because he was and because he was here, this court, the citizens who came here and who come here today, and the cause of civil justice have been, still are, and will be hereafter all much the better for it. Thank you, Stanley – – and well done.