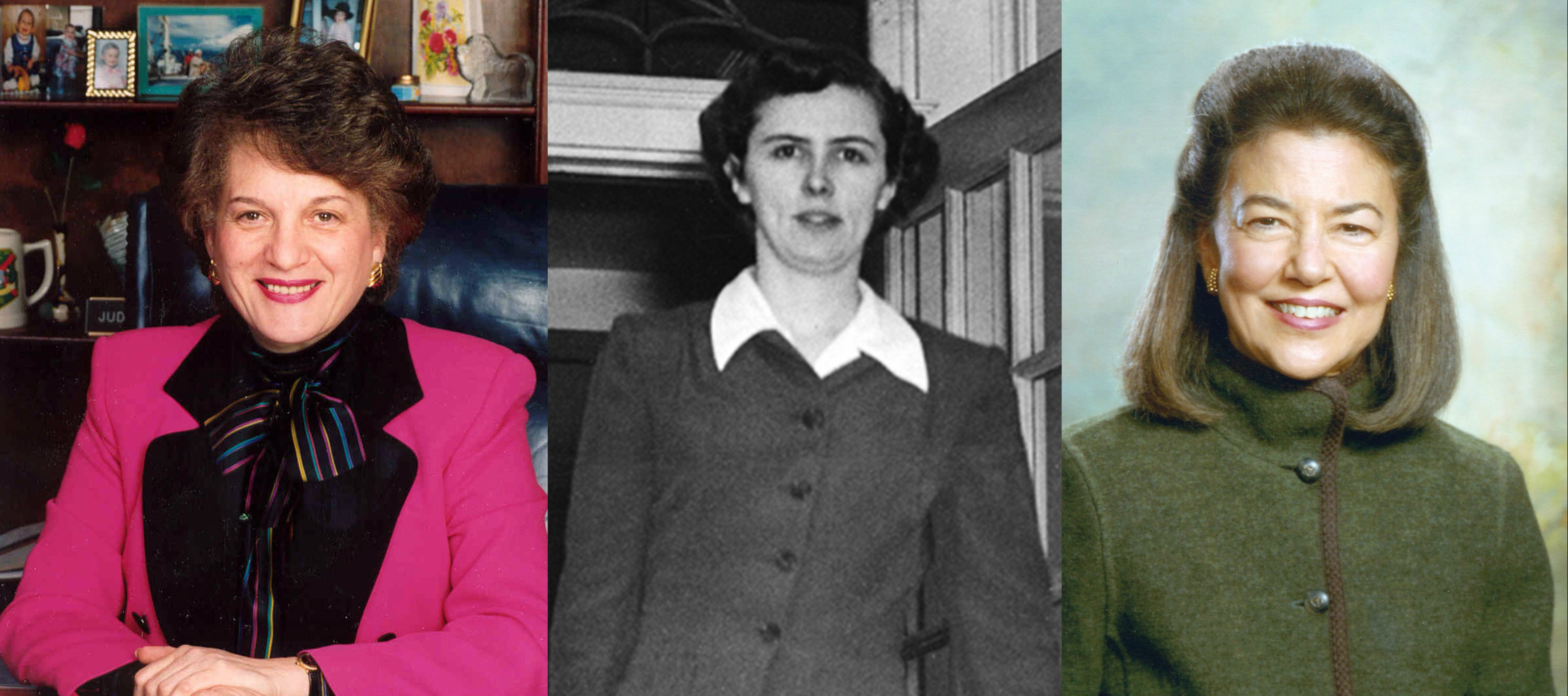

March is Women’s History Month, and we’ve been privileged to collect the oral histories of some of the pioneering women in New York law. These are Hon. Judith S. Kaye, the first woman judge on the Court of Appeals as well as the first woman Chief Judge; Charlotte Smallwood-Cook, the first woman elected District Attorney in the State; and Helaine M. Barnett, the first woman to be appointed full-time as Legal Services Corporation President. During their oral history sessions, these women reflected on the journeys that brought them to their being the “first,” and we provide excerpts here.

Hon. Judith S. Kaye, on breaking into law firms after graduation:

[T]he more I got rejected, the more it became absolutely imperative that I get into one of those Wall Street, you know, white shoe law firms. I mean I just wasn’t going to take no for answer and that’s all I was getting, was no for an answer, so that made life interesting.

So here I am, back at the firm of Casey, Lane & Mittendorf, for my second interview, the only second interview that was offered to me by anyone. The person who greeted me was… a Judge of the United States District Court for the Southern District of New York, Robert Sweet. In fact, he was a member of this law firm, such a small world. But when I came into Bob Sweet’s office and he said his partners insisted that he make this offer to me, of employment, which sounded already nice to me, I didn’t know what the negative was. He said he genuinely hoped I would turn down the offer, he found it offensive. The offer was that they would pay the going rate for a man, for one of my male classmates. I think at the time it was like $7,200 a year, that’s what it was, but they would pay me $6,400. I turned that down… I did not feel that I deserved to be treated like a second-class citizen. I did fulfill Judge Sweet’s wish and turned the offer down right then and there.

But what they didn’t know, and was just unimaginable to me, was that very same day, I had an interview at Sullivan & Cromwell, which was down the street, still on Wall Street. I was still intent to get that utterly impossible offer from one of those what they called white shoe law firms. I went to Sullivan & Cromwell. I don’t recall how many people I saw. I do remember the last person who saw me made me an offer of employment at the same salary as everybody else was getting… I must have been nuts, I said, “I’d like to think it over.” Now, why did I do that, I don’t know. And I’ve repeated that story to people over the years and the last person I told it to said, if he were the one in that seat, he would have said, if you have to think it over, never mind. But fortunately… the managing partner at Sullivan & Cromwell at the time, was far more gracious than that and he said, “Fine, just let us know when you’ve made up your mind.” I sailed out of 48 Wall Street; I was on air. I knew, of course, that I would accept that offer, and I did accept that offer.

Charlotte Smallwood-Cook, on starting her campaign for District Attorney:

I tried a case, and the Sheriff told me, while I was trying it, he said, “You’d be a good DA one day — someday.” And I said thank you. I went home and told Ned [Smallwood, Charlotte’s husband], and he said, “Well, I wonder how you do that.” I said, “Let’s look it up.” So we looked it up. And then we started talking, or he started talking to other lawyers about how you’d go about it, and one of the lawyers we knew, well, said, “You can’t run for dog catcher if you don’t get approval of the county chairman, who’s Jim Nash, and he’s been county chairman 40 years.” He sort of decides who’s going to do what. So I said, OK… I called him up, went down. Went into his house and we sat and talked, and he said, “Well, now, what can I do for you?” I said, “Well, I’m thinking of running for District Attorney.” “Oh no,” he said, “you don’t want to do that.” I said, “Well, why not?” “Well,” he said, “it’s no job for a woman.” “Well, if you were a woman and got raped, would you rather be — have a prosecution by a District Attorney who was a man or a woman?” He said, “I don’t know about that, but it’s — language is bad. You don’t want to hear all that bad language.” I said, “Well, I really don’t know it, so I guess it won’t bother me, will it?” And he said, “Well, you can’t do it. We can’t let you. I’ll tell you what. We’ll give you jobs, or two jobs, that will pay a lot more than that District Attorney job.” “Well,” I said, “I don’t really want the money. I just am interested in running for District Attorney, and I’ve checked it. Ned and I have read how you do it, and all you need is to get 500 signatures of people that registered as Republicans, and file them with the officials, and then you run.” He said, “You won’t get that far. Nobody will dare sign your petition. We’ll see to that.” And I said, “You will?” And he said, “Oh, yes.” He said, “They won’t dare sign your petition.” I said, “Well” — I stood up and said, “Well, thank you for your interview, and talking to me, and we’ll see whether we’re sinking a battleship or launching one.”

Helaine M. Barnett, on how her senior thesis continues to illustrate her desire to provide equal access to justice and what brought her to work at the Legal Aid Society:

My senior thesis was entitled, “The Study of the Japanese Evacuation from the West Coast During World War II.” I would like to quote some excerpts from it because it shows how I thought as a college student and what I actually still believe today. In the introduction to my thesis, which was submitted April 1960, to the Government Department, I stated, “How American democracy, at a time when it was engaged in a death struggle against the forces of totalitarianism across the seas, came to deal with one of its own minorities, two-thirds of whom were American citizens by birth, is the central story about to be told. Such was the history of the Japanese American evacuation, in the course of which an entire ethnic community of over 100,000 people were uprooted and imprisoned, submitted to grievous personal discomfort, severe economic loss, and deprived of both legal and human rights. Evacuation was a major event in the history of American democracy. It was without precedent in the past, and with disturbing implications for the future. It was the first time the government condemned a large group of people to barbed wire enclosures. It was the first time that a danger to national welfare was determined by group characteristics, rather than by individual guilt. Race alone determined when an individual would remain free or would become incarcerated. There were no charges filed and persons with as little as one-sixteen percent of Japanese blood were included. The decision in the short-run affected only a minority of the national population, but in the long-run, it affected the whole people.” In 2011, the U.S. Department of Justice finally acknowledged that the Solicitor General’s defense of the internment policy had been in error…

I wanted to go to work for an organization whose sole mission was to give some semblance of reality to the goal of equal access to justice, and I believed that providing legal services to the poor is not only central to fundamental fairness, due process, and equal protection of the law, but it is how the law may be used as a means of correcting inequities and abuses, and for securing rights for the disadvantaged. It is also a recognition of the importance and value of providing a voice for those not able to represent themselves and whose pressing concerns are not always foremost in the minds of the policymakers and the public. And so began my lifelong career in the provision of legal services to the poor and the pursuit of equal access to justice.

As these trailblazing women illustrate, our oral histories are treasure troves of personal stories from some of New York’s judges and legal luminaries. These three women, like many of our oral history participants, discuss their early lives, how they became involved in their careers, and the trajectory their careers have taken. See who else has participated in our oral histories here!