Description

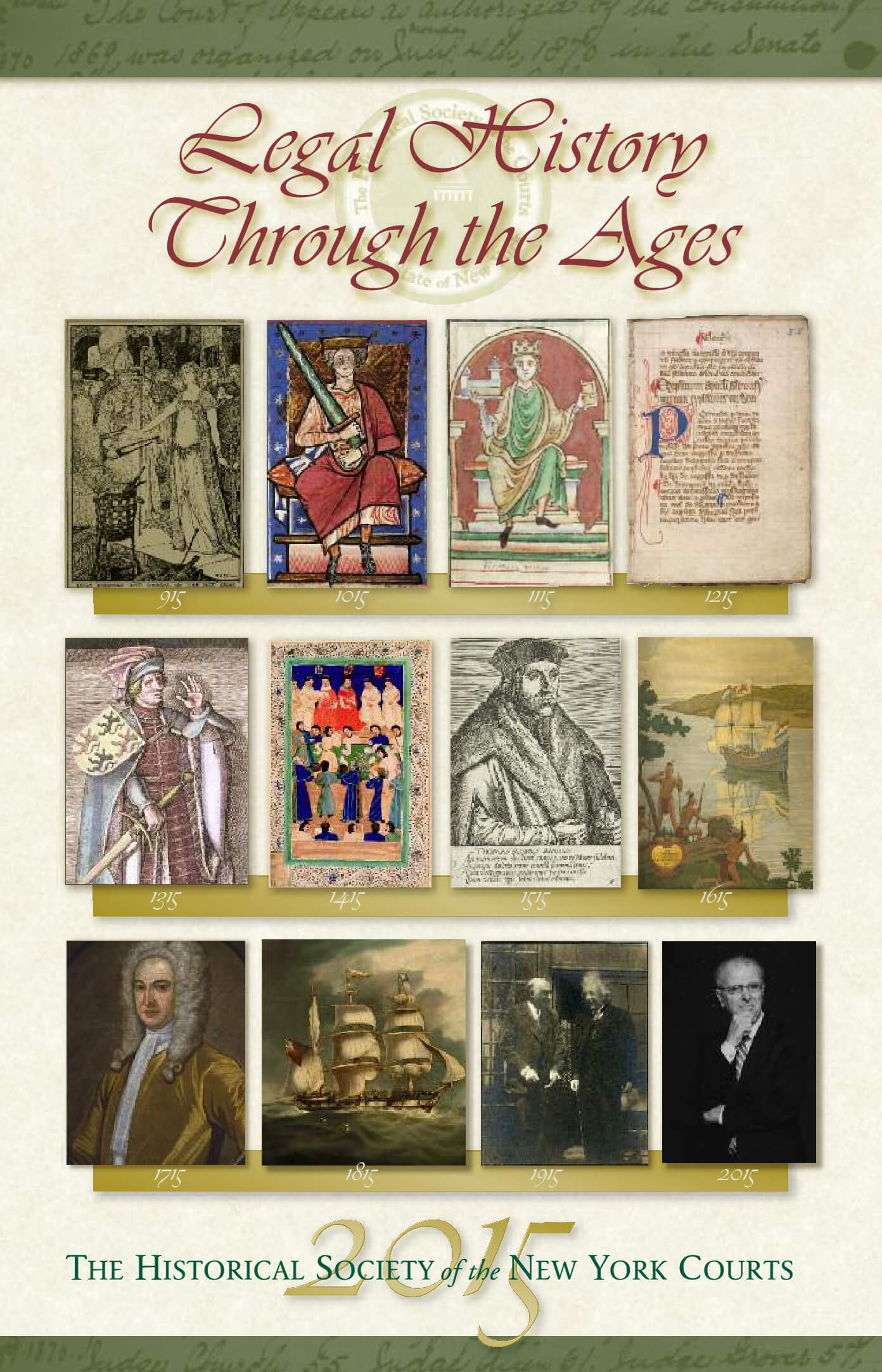

915: Trial by Ordeal

Trial by ordeal was an ancient practice used to determine guilt or innocence for all manner of crimes. In Europe during the 10th century trial by ordeal was in its heyday, and was commonly employed to adjudicate charges of religious heresy or sexual impurity. It involved subjecting the party to a barbaric test where survival, believed to be under divine control, was proof of innocence. Trial by ordeal followed the swearing of an oath by a witness to a crime, and formed the basis of an accused’s “trial” and “verdict.”

For example, the accused might be required to hold a scalding object for a designated period of time in a bare hand with the verdict depending upon the degree of injury caused and the length of time it took to heal. A healing deemed proper of innocence reflected God’s intervention. A healing deemed contrary to God’s intervention could result in loss of limb or life.

A similar process was employed in trial by water. Here, an accused who floated was believed guilty, but one who sank was deemed innocent. Unfortunately, this sometimes resulted in drowning of the accused, though they were intended to be hauled out of the water – clearly a no win situation. It is reported that trial by water was used in the New World and during the time of the Salem witch trials.

Priestly cooperation in trials by fire and water was forbidden by Pope Innocent III at the Fourth Lateran Council of 1215, but the practice was discontinued only in the 16th century. (See generally Robert Bartlett, Trial by Fire and Water: The Medieval Judicial Ordeal 24, (1986).

Image Caption:

Inga Endures the Ordeal of the Hot Iron, by H.J. Ford, from The Book of Princes and Princesses, ed. Andrew Lang, (Longmans, Green, and Co.: New York, 1908), p. 92.

February 2015

1015: Anglo-Saxon Law: Early Codes

In 1018 at Oxford, early in the reign of King Canute (1016–1035), the Danes and the English came together to agree on a code of laws. This Old English Code accepted the laws of Edgar I (King of England, 959–975) and formed the basis for an Anglo-Danish settlement. It was composed by Archbishop Wulfstan, and is an adapted version of the code of 1008 of Æthelred I, and foreshadows the fuller promulgation of Canute’s code of 1020, which covers both ecclesiastical and secular law.

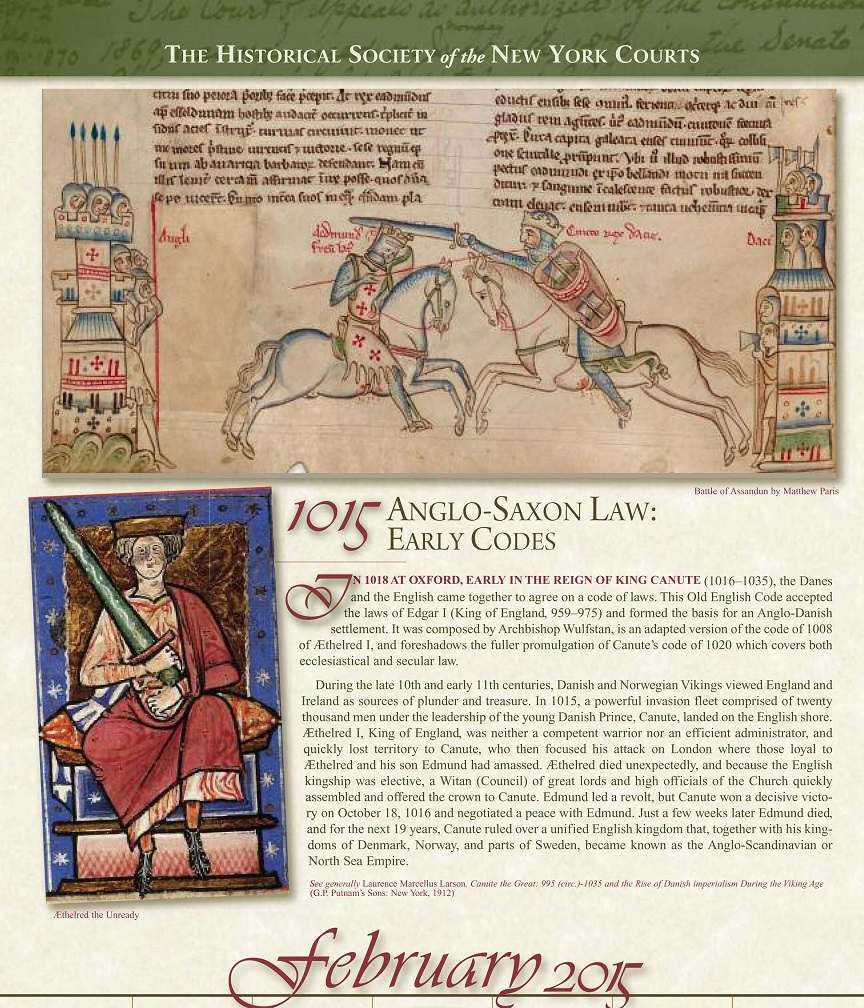

During the late 10th and early 11th centuries, Danish and Norwegian Vikings viewed England and Ireland as sources of plunder and treasure. In 1015, a powerful invasion fleet comprised of twenty thousand men under the leadership of the young Danish Prince, Canute, landed on the English shore. Æthelred I, King of England, was neither a competent warrior nor an efficient administrator, and quickly lost territory to Canute, who then focused his attack on London where those loyal to Æthelred and his son Edmund had amassed. Æthelred died unexpectedly, and because the English kingship was elective, a Witan (Council) of great lords and high officials of the Church quickly assembled and offered the crown to Canute. Edmund led a revolt, but Canute won a decisive victory on October 18, 1016 and negotiated a peace with Edmund. Just a few weeks later Edmund died, and for the next 19 years, Canute ruled over a unified English kingdom that, together with his kingdoms of Denmark, Norway, and parts of Sweden, became known as the Anglo-Scandinavian or North Sea Empire.

Source: Laurence Marcellus Larson. Canute the Great: 995 (circ.)-1035 and the Rise of Danish imperialism During the Viking Age (G.P. Putnam’s Sons: New York, 1912)

Image Captions: Æthelred the Unready. Battle of Assandun by Matthew Paris

March 2015

1115: The Laws of Henry I

The Charter of Liberties of Henry I (1100), granted by Henry when he ascended the throne, is important in the history of law. Its importance is twofold. First, Henry formally bound himself to the laws, setting the stage for the rule of law that parliaments and parliamentarians of later ages would demand. Second, it reads almost exactly like the Magna Carta, and served as the model for the Great Charter in 1215. See Paul Halsall (November 4, 2011), Internet Medieval Sourcebook. Retrieved from http://www.fordham.edu/halsall/sbook.asp.

The Leges Henrici Primi, a manuscript written around 1115, is considered the first English legal treatise and a turning point in the evolution of the English common law. The work, of unknown authorship, is not a formal code but a record of the legal customs of medieval England rooted in Anglo-Saxon tradition as modified by the Anglo-Normans, together with the laws then in force.

Serious crimes, including treason, murder, rape, robbery, and arson were tried before the King or his officials, and the cases were known as “royal pleas” or “pleas of the crown.” Several Justices of the Curia Regis were designated by the King to travel from county to county to collect revenues and to hold civil and criminal courts.

Henry I, son of William the Conqueror, was a man of high intelligence and his 35-year reign (1068-1135) was remembered for the peace and justice that prevailed.

See generally, Charles Warren Hollister, Henry I. (Yale University Press: New Haven, 2003)

Image Caption: Henry I by Matthew Paris. Courtesy British Library.

April 2015

1215: Magna Carta

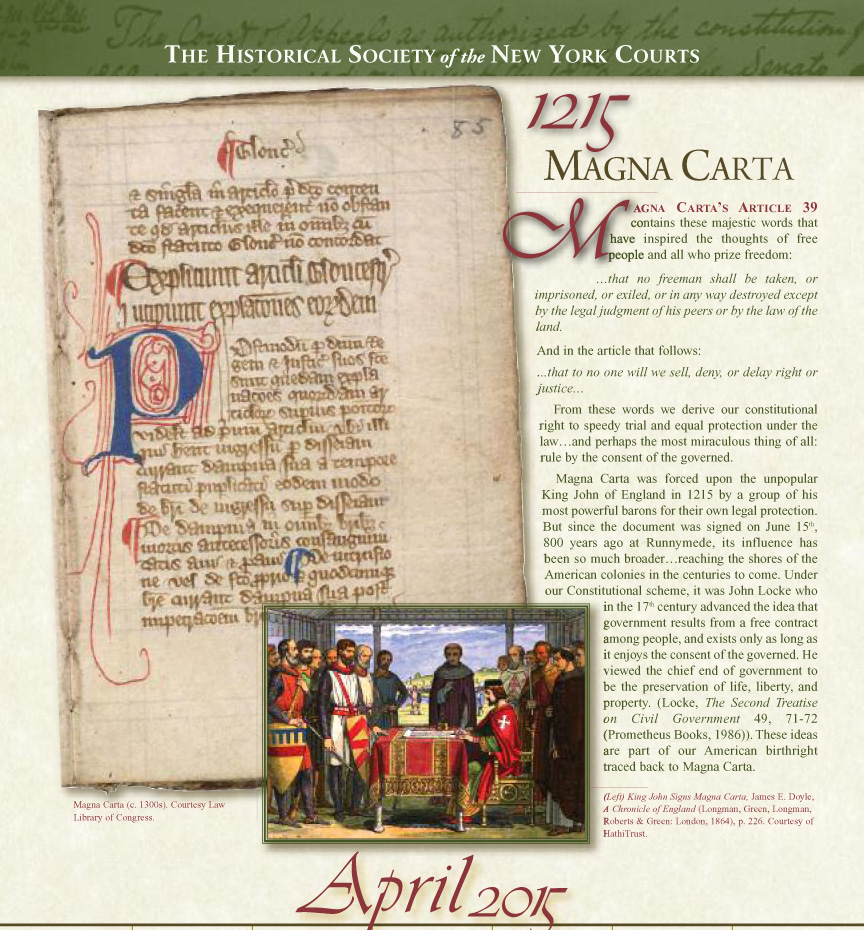

Magna Carta’s Article 39 contains the majestic words that have inspired the thoughts of free people and all who prize freedom:

…that no freeman shall be taken, or imprisoned, or exiled, or in any way destroyed except by the legal judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

And in the article that follows:

…that to no one will we sell, deny, or delay right or justice…

From these words we derive our constitutional right to speedy trial and equal protection under the law…and perhaps the most miraculous thing of all: rule by the consent of the governed.

Magna Carta was forced upon the unpopular King John of England in 1215 by a group of his most powerful barons for their own legal protection. But since the document was signed on June 15th 800 years ago at Runnymede, its influence has been so much broader…reaching the shores of the American colonies in the centuries to come. Under our Constitutional scheme, it was John Locke who in the 17th century advanced the idea that government results from a free contract among people, and exists only as long as it enjoys the consent of the governed. He viewed the chief end of government to be the preservation of life, liberty, and property. (Locke, The Second Treatise on Civil Government 49, 71-72 (Prometheus Books 1986)). These ideas are part of our American birthright traced back to Magna Carta.

Image Captions:

King John Signs Magna Carta, James E. Doyle, A Chronicle of England (Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green: London, 1864), p. 226. Courtesy of HathiTrust.

Magna Carta (c. 1300s). Courtesy Law Library of Congress.

May 2015

1315: Flushing City Rights

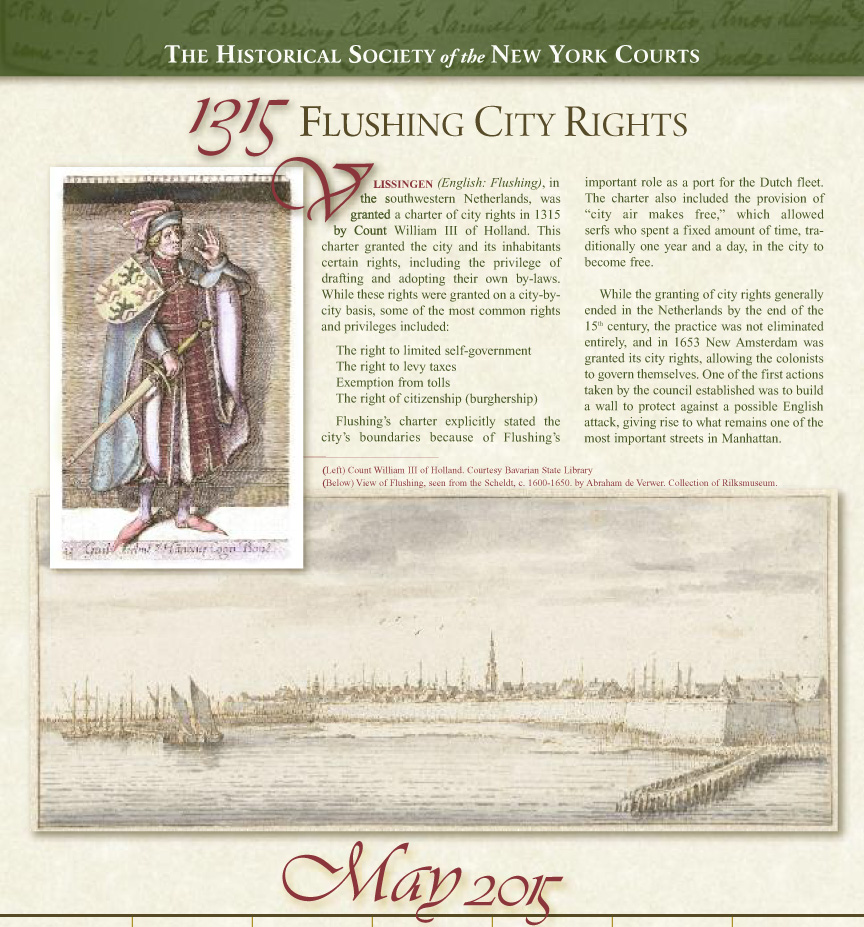

Vlissingen (English: Flushing), in the southwestern Netherlands, was granted a charter of city rights in 1315 by Count William III of Holland. This charter granted the city and its inhabitants certain rights, including the privilege of drafting and adopting their own by-laws. While these rights were granted on a city-by-city basis, some of the most common rights and privileges included:

- The right to limited self-government

- The right to levy taxes

- Exemption from tolls

- The right of citizenship (burghership)

Flushing’s charter was unique document given its important role as a port for the Dutch fleet and included explicitly stated boundaries. The charter also included the provision of “city air makes free,” which allowed serfs who spent a fixed amount of time, traditionally one year and a day, in the city to become free.

While the granting of city rights generally ended in the Netherlands by the end of the 15th Century, the practice was not eliminated entirely and in 1653 New Amsterdam was granted its municipal rights, allowing the colonists to govern themselves. One of the first actions taken by the council established was to build a wall to protect against a possible English attack, giving rise to what remains one of the most important streets on Manhattan.

Image Captions:

View of Flushing, seen from the Scheldt, c. 1600-1650. by Abraham de Verwer. Collection of Rilksmuseum.

Count William III of Holland. Courtesy University of Mannheim MATEO Project.

June 2015

1415: Court of Chancery & Chancery English

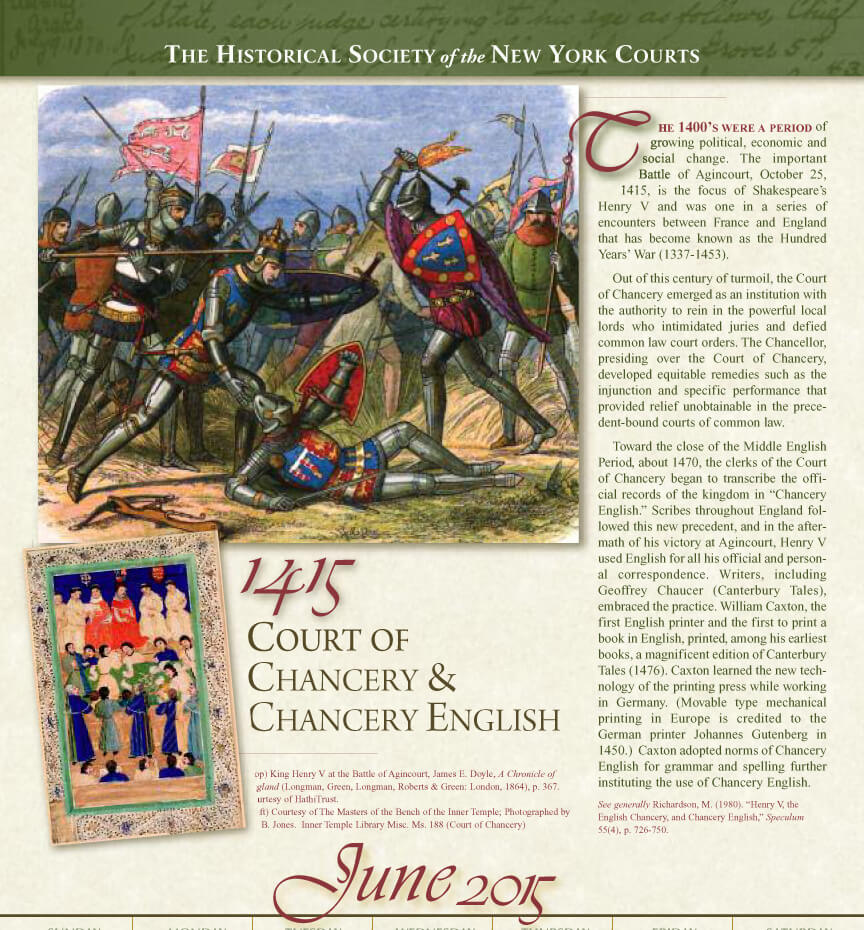

The 1400’s were a period of growing political, economic and social change. The important Battle of Agincourt, October 25, 1415, is the focus of Shakespeare’s Henry V and was one in a series of encounters between France and England that has become known as the Hundred Years’ War (1337-1453).

Out of this century of turmoil, the Court of Chancery emerged as an institution with the authority to rein in the powerful local lords who intimidated juries and defied common law court orders. The Chancellor, presiding over the Court of Chancery, developed equitable remedies such as the injunction and specific performance that provided relief unobtainable in the precedent-bound courts of common law.

Toward the close of the Middle English Period, about 1470, the clerks of the Court of Chancery began to transcribe the official records of the kingdom in “Chancery English.” Scribes throughout England followed this new precedent, and in the aftermath of his victory at Agincourt, Henry V used English for all his official and personal correspondence. Writers, including Geoffrey Chaucer (Canterbury Tales), embraced the practice. William Caxton, the first English printer and the first to print a book in English, printed, among his earliest books, a magnificent edition of Canterbury Tales (1476). Caxton learned the new technology of the printing press while working in Germany. (Movable type mechanical printing in Europe is credited to the German printer Johannes Gutenberg in 1450.) Caxton adopted norms of Chancery English for grammar and spelling further instituting the use of Chancery English.

Image Captions:

King Henry V at the Battle of Agincourt, James E. Doyle, A Chronicle of England (Longman, Green, Longman, Roberts & Green: London, 1864), p. 367. Courtesy of HathiTrust.

Courtesy of The Masters of the Bench of the Inner Temple; Photographed by B. Jones. Inner Temple Misc. Ms. 188 (Court of Chancery)

July 2015

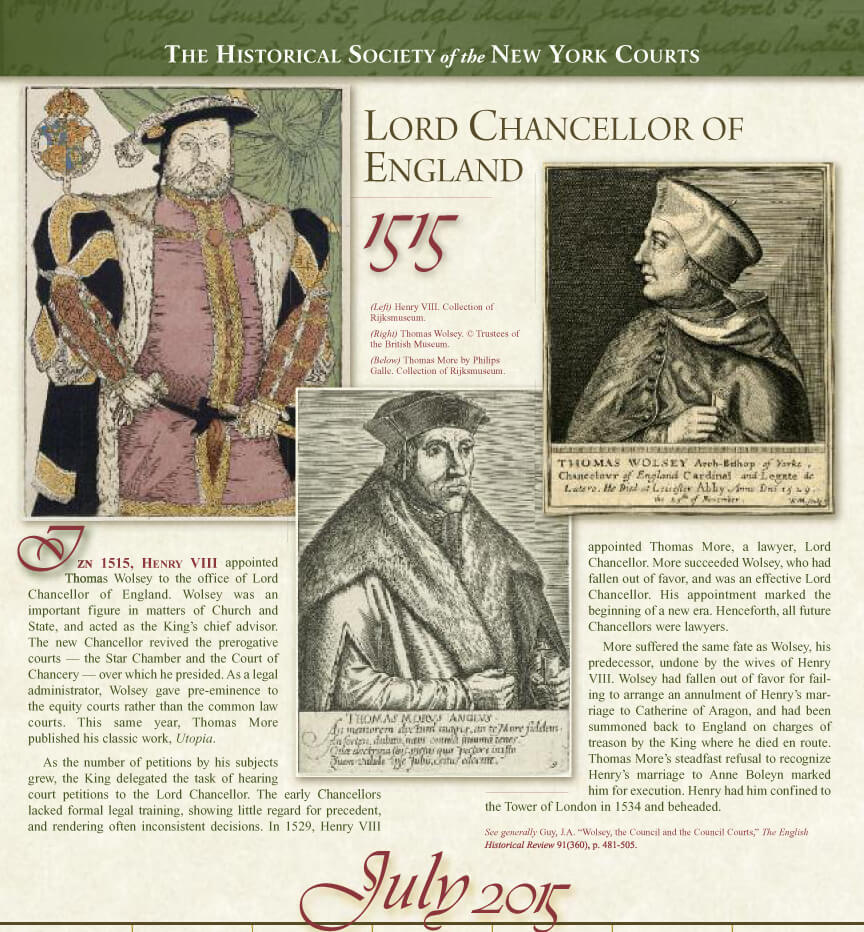

1515: Lord Chancellor of England

In 1515, Henry VIII appointed Thomas Wolsey to the office of Lord Chancellor of England. Wolsey was an important figure in matters of Church and State, and acted as the King’s chief advisor. The new Chancellor revived the prerogative courts – the Star Chamber and the Court of Chancery – over which he presided. As a legal administrator, Wolsey gave pre-eminence to the equity courts rather than the common law courts. This same year, Thomas More published his classic work, Utopia.

As the number of petitions by his subjects grew, the King delegated the task of hearing court petitions to the Lord Chancellor. The early Chancellors lacked formal legal training, showing little regard for precedent, and rendering often inconsistent decisions. In 1529, Henry VIII appointed Thomas More, a lawyer, Lord Chancellor. More succeeded Wolsey, who had fallen out of favor, and was an effective Lord Chancellor. His appointment marked the beginning of a new era. Henceforth, all future Chancellors were lawyers.

More suffered the same fate as Wolsey, his predecessor, undone by the wives of Henry VIII. Wolsey had fallen out of favor for failing to arrange an annulment of Henry’s marriage to Catherine of Aragon. He has been summoned back to England on charges of treason by the King where he died en route. Thomas More’s steadfast refusal to recognize Henry’s marriage to Anne Boleyn marked him for execution. Henry had him confined to the Tower of London in 1534 and beheaded.

See Generally, Guy, J.A. “Wolsey, the Council and the Council Courts” The English Historical Review 91(360), p. 481-505.

Image Captions:

Thomas More by Philips Galle. Collection of Rijksmuseum.

Thomas Wolsey. © Trustees of the British Museum.

Henry VIII. Collection of Rijksmuseum.

August 2015

1615: Right of First Discovery

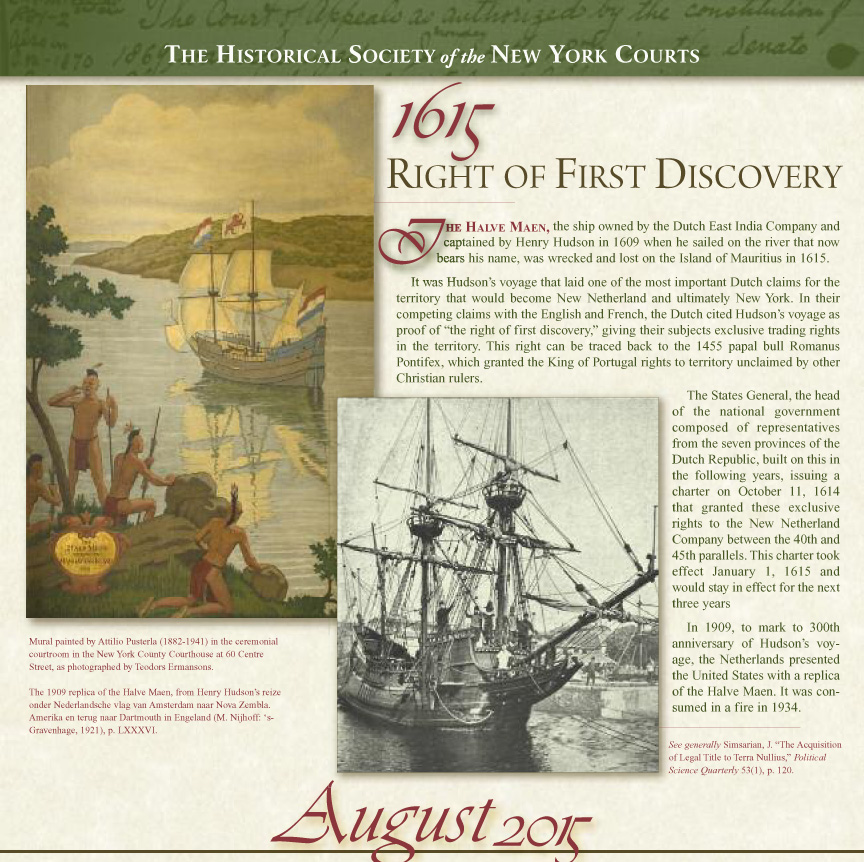

The Halve Maen, the ship owned by the Dutch East India Company and captained by Henry Hudson in 1609 when he sailed on the river that now bears his name, was wrecked and lost on the Island of Mauritius in 1615.

It was Hudson’s voyage that laid one of the most important Dutch claims for the territory that would become New Netherland and ultimately New York. In their competing claims with the English and French, the Dutch cited Hudson’s voyage as proof of “the right of first discovery,” giving their subjects exclusive trading rights in the territory. This right can be traced back to the 1455 papal bull Romanus Pontifex, which granted the King of Portugal rights to territory unclaimed by other Christian rulers.

The States General, the head of the national government composed of representatives from the seven provinces of the Dutch Republic, built on this in the following years, issuing a charter on October 11, 1614 that granted these exclusive rights to the New Netherland Company between the 40th and 45th parallels. This charter took effect January 1, 1615 and would stay in effect for the next three years

In 1909, to mark to 300th anniversary of Hudson’s voyage, the Netherlands presented the United States with a replica of the Halve Maen. It was consumed in a fire in 1934.

See Simsarian, J. “The Acquisition of Legal Title to Terra Nullius,” Political Science Quarterly 53(1), 120.

Image Captions:

Mural painted by Attilio Pusterla (1882-1941) in the ceremonial courtroom in the New York County Courthouse at 60 Centre Street, as photographed by Teodors Ermansons.

The 1909 replica of the Halve Maen, from Henry Hudson’s reize onder Nederlandsche vlag van Amsterdam naar Nova Zembla. Amerika en terug naar Dartmouth in Engeland (M. Nijhoff: ‘s-Gravenhage, 1921), p. LXXXVI.

September 2015

1715: Judge and Chief Judge of the New York Supreme Court of Judicature, 1715-1735

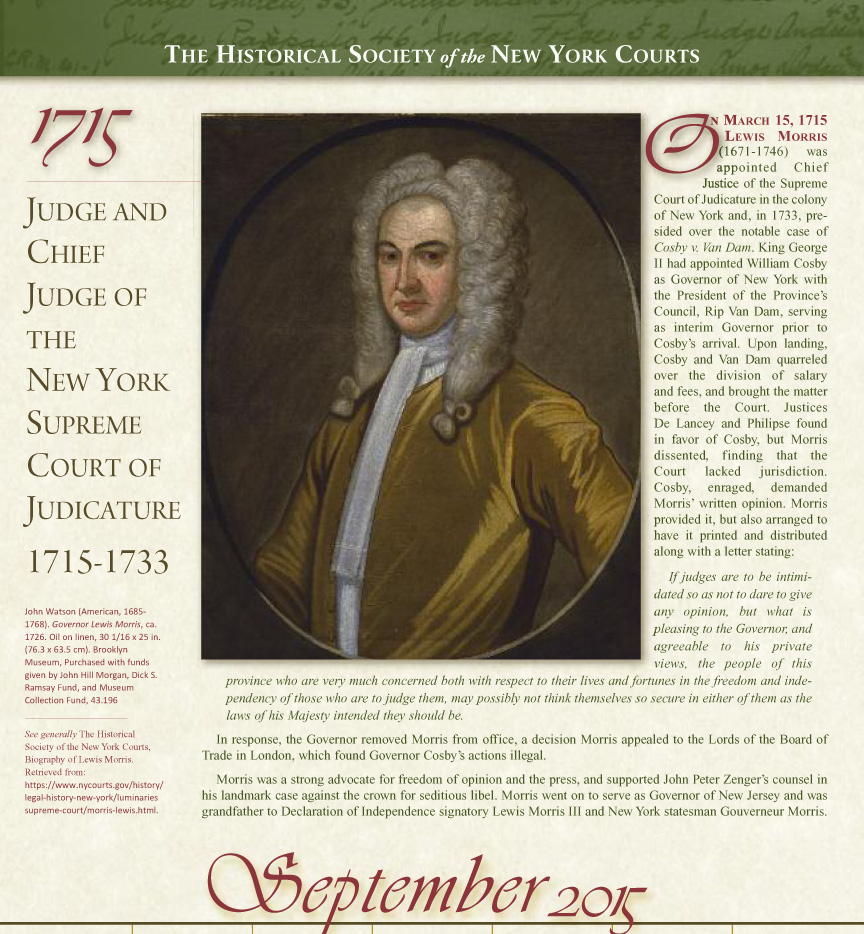

On March 15, 1715. Lewis Morris (1671-1746) was appointed Chief Justice of the Supreme Court of Judicature in the colony of New York, presiding over the notable case of Cosby v. Van Dam in 1733. King George II had appointed William Cosby as Governor of New York with the President of the Province’s Council, Rip Van Dam, serving as interim Governor prior to Cosby’s arrival. Upon landing, Cosby and Van Dam quarreled over the division of salary and fees, and brought the matter before the Court. Justices De Lancey and Philipse found in favor of Cosby, but Morris dissented, finding that the Court lacked jurisdiction. Cosby, enraged, demanded Morris’ written opinion.Morris provided it, but also arranged to have it printed and distributed along with a letter stating:

If judges are to be intimidated so as not to dare to give any opinion, but what is pleasing to the Governor, and agreeable to his private views, the people of this province who are very much concerned both with respect to their lives and fortunes in the freedom and independency of those who are to judge them, may possibly not think themselves so secure in either of them as the laws of his Majesty intended they should be.

In response the Governor removed Morris from office, a decision Morris appealed to the Lords of the Board of Trade in London, which found Governor Cosby’s actions illegal.

Morris was a strong advocate for freedom of opinion and the press, and supported John Peter Zenger’s counsel in his landmark case against the crown for seditious libel. Morris went on to serve as Governor of New Jersey and was grandfather to Declaration of Independence signatory Lewis Morris III and New York statesman Gouverneur Morris.

See generally, Lewis Morris. Retrieved from https://www.nycourts.gov/history/legal-history-new-york/luminaries-supreme-court/morris-lewis.html.

Image Caption:

John Watson (American, 1685-1768). Governor Lewis Morris, ca. 1726. Oil on linen, 30 1/16 x 25 in. (76.3 x 63.5 cm). Brooklyn Museum, Purchased with funds given by John Hill Morgan, Dick S. Ramsay Fund, and Museum Collection Fund, 43.196

October 2015

1815: Wetmore v. Henshaw, 12 Johns. Rep. 324 (August Term, 1815)

Admiralty jurisdiction in the United States has its origins in the English High Court of Admiralty and the subordinate colonial Vice Admiralty Courts. After independence, individual States established admiralty courts from which, at a later date, appeals could be taken to a court of appeals created by Congress under the Articles of Confederation. The development of a uniform body of maritime law through federal courts promoted commerce by removing the obstacle of competing State laws.

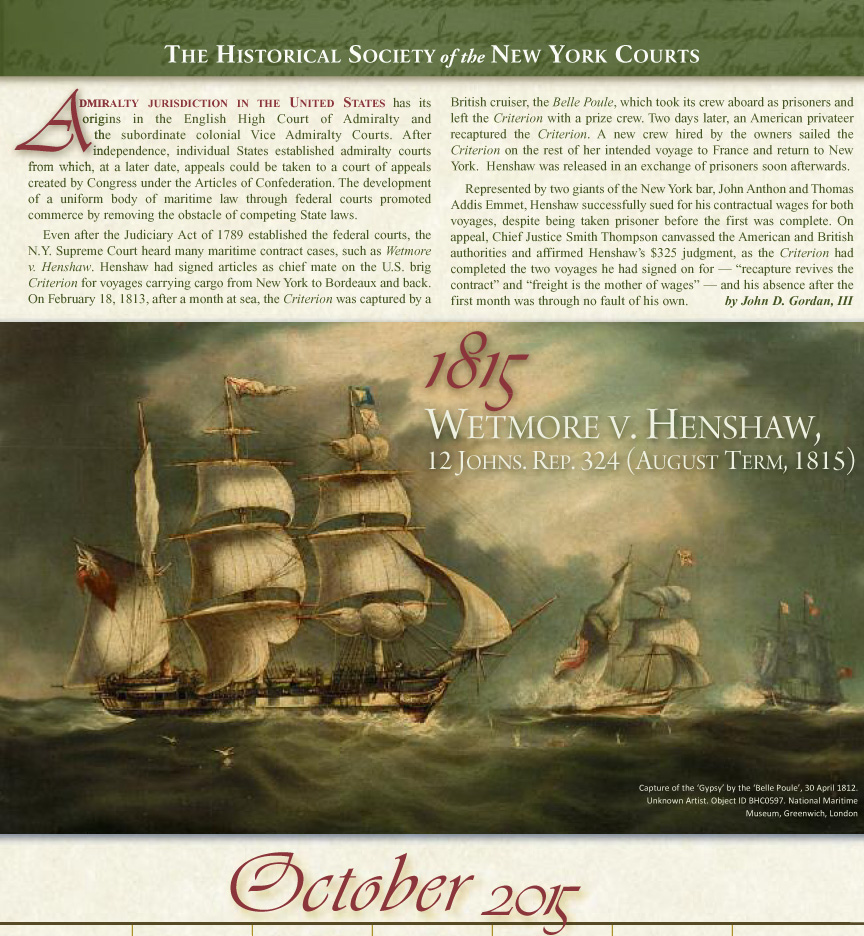

Even after the Judiciary Act of 1789 established the federal courts, the N.Y. Supreme Court heard many maritime contract cases, such as Wetmore v. Henshaw. Henshaw had signed articles as chief mate on the U.S. brig Criterion for voyages carrying cargo from New York to Bordeaux and back. On February 18, 1813, after a month at sea, the Criterion was captured by a British cruiser, the Belle Poule, which took its crew aboard as prisoners and left the Criterion with a prize crew. Two days later, an American privateer recaptured the Criterion. A new crew hired by the owners sailed the Criterion on the rest of her intended voyage to France and return to New York. Henshaw was released in an exchange of prisoners soon afterwards.

Represented by two giants of the New York bar, John Anthon and Thomas Addis Emmet, Henshaw successfully sued for his contractual wages for both voyages, despite being taken prisoner before the first was complete. On appeal, Chief Justice Smith Thompson canvassed the American and British authorities and affirmed Henshaw’s $325 judgment, as the Criterion had completed the two voyages he had signed on for – “recapture revives the contract” and “freight is the mother of wages” – and his absence after the first month was through no fault of his.

Image Caption:

Capture of the ‘Gypsy’ by the ‘Belle Poule’, 30 April 1812. Unknown Artist. Object ID BHC0597. National Maritime Museum, Greenwich, London.

November 2015

1915: Albert Einstein and the General Theory of Relativity

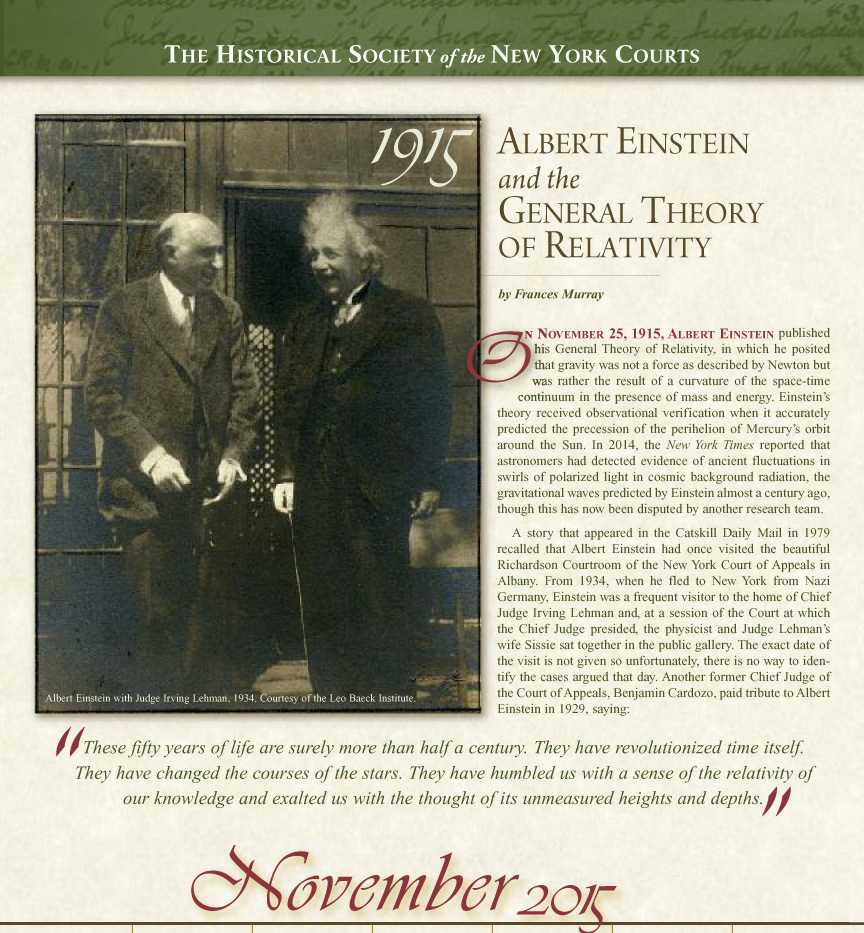

On November 25, 1915, Albert Einstein published his General Theory of Relativity, in which he posited that gravity was not a force as described by Newton but was rather the result of a curvature of the space-time continuum in the presence of mass and energy. Einstein’s theory received observational verification when it accurately predicted the precession of the perihelion of Mercury’s orbit around the Sun. In 2014, the New York Times reported that astronomers had detected evidence of ancient fluctuations in swirls of polarized light in cosmic background radiation, the gravitational waves predicted by Einstein almost a century ago.

A story that appeared in the Catskill Daily Mail in 1979 recalled that Albert Einstein had once visited the beautiful Richardson Courtroom of the New York Court of Appeals in Albany. From 1934, when he fled to New York from Nazi Germany, Einstein was a frequent visitor to the home of Chief Judge Irving Lehman and, at a session of the Court at which Chief Judge presided, the physicist and Judge Lehman’s wife Sissie sat together in the public gallery. The exact date of the visit is not given so unfortunately, there is no way to identify the cases argued that day. Another former Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Benjamin Cardozo, paid tribute to Albert Einstein in 1929, saying: “These fifty years of life are surely more than half a century. They have revolutionized time itself. They have changed the courses of the stars. They have humbled us with a sense of the relativity of our knowledge and exalted us with the thought of its unmeasured heights and depths.”

Image Captions:

Albert Einstein with Judge Irving Lehman, 1934. Courtesy of the Leo Baeck Institute.

December 2015

2015: Chief Judge Jonathan Lippman

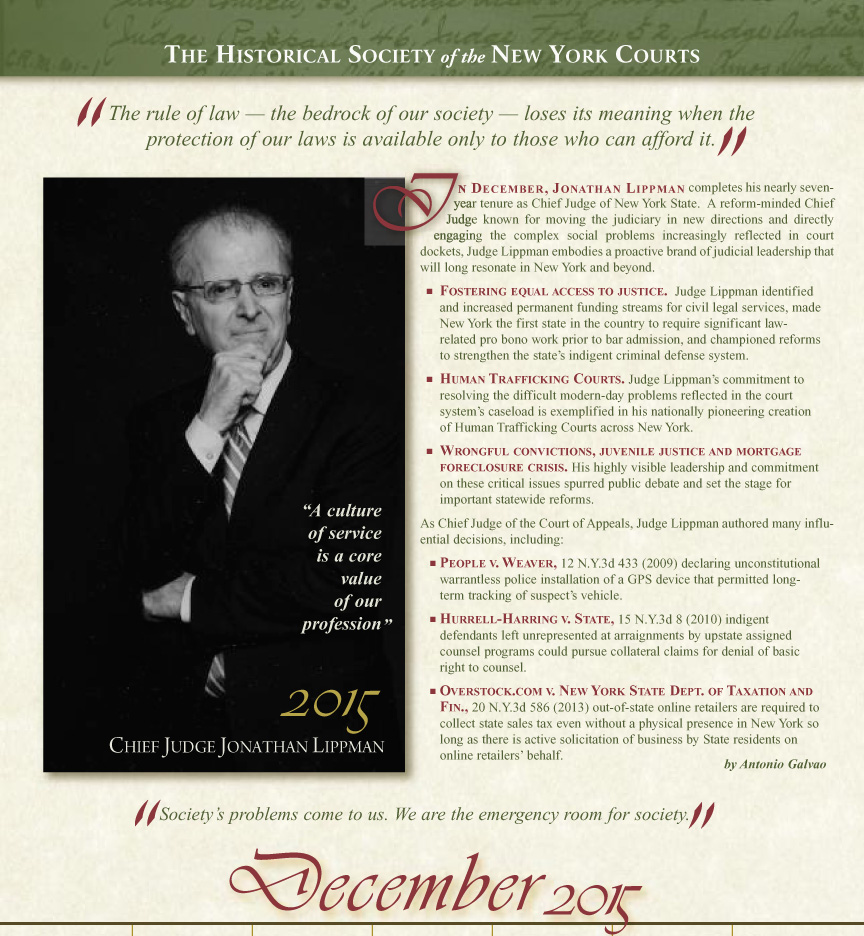

In December, Jonathan Lippman completes his nearly seven-year tenure as Chief Judge of New York State. A reform-minded Chief Judge known for moving the judiciary in new directions and directly engaging the complex social problems increasingly reflected in court dockets, Judge Lippman embodies a proactive brand of judicial leadership that will resonate in New York and beyond.

∙ Fostering equal access to justice. Judge Lippman identified and increased permanent funding streams for civil legal services, made New York the first state in the country to require significant law-related pro bono work prior to bar admission, and championed reforms to strengthen the state’s indigent criminal defense system.

∙ Human Trafficking Courts. Judge Lippman’s commitment to resolving the difficult modern-day problems reflected in the court system’s caseload is exemplified in his nationally pioneering creation of Human Trafficking Courts across New York.

∙ Wrongful convictions, juvenile justice and mortgage foreclosure crisis. His highly visible leadership and commitment on these critical issues spurred public debate and set the stage for important statewide reforms.

As Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals, Judge Lippman authored many influential decisions, including:

∙ People v. Weaver, 12 N.Y.3d 433 (2009)declaring unconstitutional warrantless police installation of a GPS device that permitted long-term tracking of suspect’s vehicle.

∙ Hurrell-Harring v. State, 15 N.Y.3d 8 (2010) indigent defendants left unrepresented at arraignments by upstate assigned counsel programs could pursue collateral claims for denial of basic right to counsel.

∙ Overstock.com v. New York State Dept. of Taxation and Fin., 20 N.Y.3d 586 (2013) out-of-state online retailers are required to collect state sales tax even without a physical presence in New York so long as there is active solicitation of business by State residents on online retailers’ behalf.