This article was written by Rachel Cavell, a practicing attorney with an office in Kingston, New York. Ms. Cavell is also a faculty associate with the Bard College Institute for Writing and Thinking, the Language and Thinking Program, and the Bard Prison Initiative. She received her degree in English Literature from Harvard University.

The workshops were led by Ms. Cavell; William Dixon, IWT Associate and Director, Bard College Language and Thinking program; and Teresa Vilardi, IWT Associate. They were held at Rochester Central School District in December 2016 and at Bard College in February 2017.

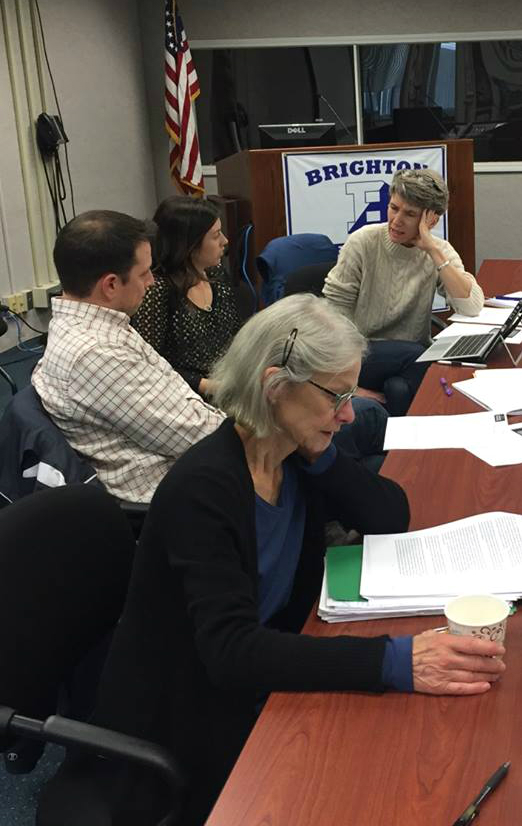

Photo: Educators participate in professional development workshops sponsored by the Historical Society of the NY Courts and Bard College Institute of Writing and Thinking

For several years, The Historical Society of the New York Courts has provided generous funding to Bard College for the preparation and implementation of courses geared towards teaching high school students about the New York courts and the Federal judiciary. Following a successful collaboration with the Bard High School Early Colleges in New York City, the Historical Society turned its attention to the Bard College Institute for Writing and Thinking, an organization that offers professional development to high school and college teachers seeking to enrich and enliven learning through writing-rich exercises. In an effort to achieve a diverse and disparate group of students and teachers, we focused our training on school districts in the Rochester, lower and mid-Hudson areas, holding two successful workshops entitled “Justice and the New York Courts” this past December (2016) and February (2017).

Thanks to the collaboration with the Historical Society, my colleagues at the Institute, together with high school teachers from Harlem to Newburgh to Rochester, had the privilege of spending two Fridays considering how and in what way the Framers of our Constitution first conceived of the independence of the judiciary. It was our goal to make this question as real to students today as it would have been to the Framers of our Constitution. Readings included sections from Hamilton’s Federalist Papers (#78), the famous 1852 Lemmon Slave Case from New York, and journalistic pieces, among others.

As it happened, by the time of the first workshop, we found ourselves recovering from an extremely contentious Presidential election and, by February, were embroiled in a genuine Constitutional crisis, involving what can only be described as a stand-off between the Executive and the Judicial branches of our Federal government (the Injunction against the President’s February 2017 Executive Order on Immigration had been upheld by the Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit just the day before). The question of judicial independence was now of pressing and immediate national concern.

In The Federalist Papers, Hamilton asserts that “there is no liberty, if the power of judging be not separated from the legislative and executive powers.” We began both workshops by asking the participants to dissect and consider this sentiment. Reading 18th century high diction is not unlike learning a second language, for ourselves and certainly for our students. To make this language intelligible, we kept bringing it back to our present moment: What do you suppose would happen if the power of judging were not separated from the legislative and executive powers? What is hard about this idea? What is easy about this idea? How does the Lemmon Slave Case complicate or add to this Hamiltonian notion?

Our goal was to elucidate to our participants that making history real means at times resisting the temptation to provide students with dates and names but instead to throw them into the deep end with questions to ponder and answers that seem impossible. After reading the Lemmon Slave Case (in which the New York Court of Appeals in 1860 affirmed the lower courts’ ruling that the Fugitive Slave Law was inapplicable to the circumstances therein and thus granted freedom to the slaves) we gave the participants an 1860 “op ed” article critical of the decision, posing to the students the following exercise: The editorial argues that the court has wrongly “arm[ed]” judges with the legislative power, because the decision was made not on law but rather on the judges’ own notions of “justice and comity.” We then asked them to write one thing that they are willing to believe about that claim, even if only provisionally, and one thing that they are willing to doubt, again perhaps only provisionally. In their “believing” and “doubting”, we instructed them to draw upon language that they noted earlier from other people’s translations/responses to the editorial. The difficulty with this exercise was manifold: It asked the students to expand upon their habits of thinking by taking one position and then consciously and deliberately taking its other side; it asked them to question their assumption that the Lemmon case was decided correctly and may have in fact over-reached its judicial authority; and finally, it asked them to make these thoughts clear in writing.

The advantages of this kind of experiential approach to writing pedagogy are that the students unwittingly start to speak the language of the texts they are reading, discovering in this process that documents that feel old and foreign are actually written by people who have something to say, and that they have something to say in response. Where historical “context” is sometimes missing in this practice, contemporary relevance and personal connection is gained. In a 2009 journalistic piece written by Supreme Court Justice Sonia Sotomayor given to our workshop participants, Sotomayor disagrees with President Barack Obama’s assertion that in a certain percentage of judicial decisions “the critical ingredient” is what is in the judge’s “heart”. To the contrary argues Sotomayor, judges must always decide based upon facts and law, not upon their empathy with one party or another. Reading this article at the end of our workshop day together and questioning whether they agreed with the position taken by President Obama or Justice Sotomayor, our workshop participants were able to see a direct line of argumentation beginning with Hamilton and continuing to the present: To what extent must judges adhere to precedent and when may they exert independent judgment? When should the judiciary interfere in determinations rendered by the other branches and in what cases must they defer?

By pressing these questions and bringing them back to the present moment, it becomes undeniably clear that the questions raised and discussed by the founding Fathers are still present today; by implication it becomes clear that in order to understand what is so extraordinary about a judicial overruling of a 2017 Executive Order one must understand those earliest Federalist documents in which the independence of the judiciary was not only formulated but posited as an essential defining characteristic of a functioning democracy. We need to look backwards now more than ever in order to see a way forward. It is our hope that these workshops and that our alliance with the Historical Society of the New York Courts will help us to forge a pathway in both of these directions.

Comments · 1

Comments are closed.