The theme for Law Day 2019 is Free Speech, Free Press, Free Society, and early New York cases tested some of the protections of the First Amendment. One such case is People v. Croswell (1804), and in 2011, we published an article written by Paul McGrath in our journal Judicial Notice on Alexander Hamilton’s role in the trial. In the spirit of Law Day, we have excerpted a part below.

Paul McGrath retired after serving as Chief Court Attorney of the New York Court of Appeals in Albany where he supervised the Court’s Central Legal Research Staff. Prior to his promotion to Chief Court Attorney, Mr. McGrath worked as the Deputy Chief Court Attorney of the Court of Appeals and as a Law Clerk to Associate Judge Richard D. Simons. Mr. McGrath earned his J.D., magna cum laude, from the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Law and his B.A., magna cum laude, from the State University of New York College at Geneseo.

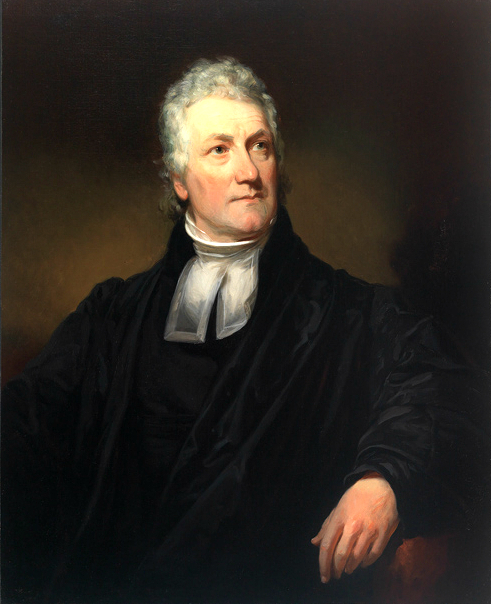

Photo: Harry Croswell (1778-1858) by Henry Inman, 1839. Courtesy of Mead Art Museum, Amherst College. Bequest of Herbert L. Pratt (Class of 1895), AC 1945.12

The Motion for a New Trial

Before judgment could be pronounced, Croswell’s attorneys quickly moved for a new trial, arguing initially (1) that the truth should be permitted in evidence as a justification and thus that Chief Justice [Morgan] Lewis had erred in denying the motion for a further adjournment, and (2) that the court had misdirected the jury. Following accepted practice of the time, the motion for a new trial would be heard by the entire five-justice Supreme Court — somewhat like an appeal of the judgment in modern practice. The defense attorneys would employ a legal device called the “case stated.” By “making a case,” essentially a set of facts to which the prosecution and defense stipulated, all objectionable matters, including any not in the record proper such as the jury charge which at the time was a matter outside the record, could be considered by the full Court.25 Following certain adjournments, the case was finally heard in February 1804 with the Supreme Court sitting in Albany. In accord with the practice of the day, the parties would not exchange briefs before the argument.26

The defense team used the time to regroup. The Federalists sought out Alexander Hamilton who, according to Justice (later Chancellor) James Kent, was “universally conceded” to be the preeminent lawyer of the era.27 As early as June 23, 1803, they had persuaded General Philip Schuyler, Hamilton’s father-in-law, to write the former Secretary of the Treasury for help. The rabid Federalist Schuyler described the case as “a libel against that Jefferson, who disgraces not only the place he fills but produces Immorality by his pernicious example.”28 Although there is some evidence that Hamilton played an advisory role in the Croswell trial in the Circuit Court, other matters had precluded his appearing there. Now he was ready to enter the proceedings in person, gratis.

To a modest degree, Hamilton’s strategy was affected by recent events that had occurred in Virginia. On July 17, 1803, Croswell’s potential star witness, James Callender, apparently in the midst of a drinking spree, fell (or perhaps was pushed) out of a boat and found a final resting place, as one contemporary put it, “in congenial mud,” at the bottom of the James River.29 But Callender did leave behind his papers, including letters Jefferson had written expressing his approval of The Prospect Before Us, evidence that could potentially be used by Hamilton if the Court were to grant a new trial. Indeed, theoretically at least, at any retrial Hamilton might try to subpoena Jefferson himself, or at least to secure Jefferson’s affidavit on the truth of the Callender matter. Any retrial might prove embarrassing to the President.

Hamilton’s Opportunity

For Hamilton, the Croswell case was an opportunity not to be missed. First, and perhaps foremost, it gave him a chance to strike back at Jefferson, his old rival in the Washington administration. Second, it provided Hamilton with a means to further his view of American constitutionalism. Although far from a populist, Hamilton did understand that a free press was more critical in America than in Britain, and that freedom of the press was a great issue on which to win back to the Federalist cause the favor of the electorate. Hamilton could argue for a cautious view of freedom of the press, in which the motive of the author would be the critical component in assessing liability.

The Croswell case also gave Hamilton an opportunity to highlight his brilliance as a thinker and orator in a case that was far more understandable to the general public than his typical practice of maritime insurance cases or land grant disputes. Hamilton was “skilled in the rhetoric of dress and behavior” and this asset only enhanced the persuasiveness of his legal argument.30 Finally, for Hamilton — who was now known as General Hamilton, for his service as acting commander of the American army between 1798 and 1800 in the so-called Quasi-War with France — a big victory in Croswell might restore a portion of his lost reputation. Hamilton expected, and even desired, a war with Napoleon’s France — a real possibility in 1804 — and the press coverage of Croswell could only raise his stature in the minds of the Federalist leaders.

Hamilton assembled a formidable defense team. He retained the services of William W. Van Ness, who had appeared for Croswell in the Circuit Court. Hamilton also recruited his old friend and fellow Federalist Richard Harison, who had served as an Assistant Attorney General during the Washington administration.