In 725, the Kingdom of Kent lost its predominance in Anglo-Saxon England and the center of power moved to the Kingdom of Wessex. The kings of Wessex gradually expanded the area under their rule through annexation and conquest and, by the year 821, a large part of England was under the governance of the Crown of Wessex.

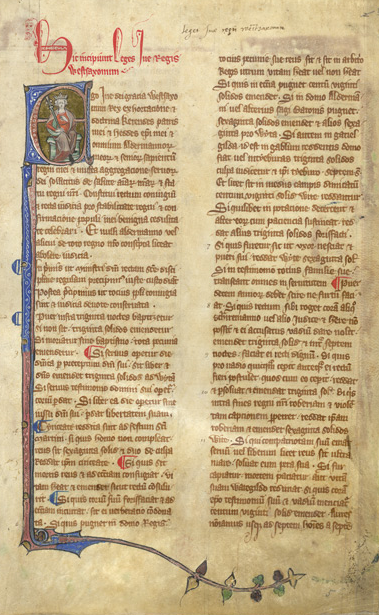

The Dooms of Ine (c 670-728 AD)

Ine, King of Wessex, issued Dooms in the year 694. Unfortunately, none of the original manuscripts survive and the sole version available to us today is annexed to a later document, the Dooms of Alfred the Great. In that version of Ine’s Dooms, the first several clauses relate to the Catholic church and seek to promote the practice of Christianity. Other dooms include penalties for fighting, stealing, slave trading and murder. Procedurally, the Dooms addressed the administration of oaths and perjury, and widened the definition of a surety by removing the requirement that person acting as surety be a member of the accused’s Maegth (kindred). New dooms relating to land usage and tenures indicate a fundamental change taking place in Anglo-Saxon society as it became more agrarian.

The Dooms of Alfred the Great (849-899 AD)

Alfred the Great came to the throne of Wessex in 871 at the age of 21. He was a warrior king, an expert in military defenses and naval warfare, and he successfully led the Anglo-Saxon resistance to the Viking invaders. During the war with the Vikings, the kingdom’s legal system fell into abeyance and, with victory, came the task of rebuilding. As Alfred stated in the prologue to the Domboc (Book of Dooms)

I, King Alfred, collected these together and ordered to be written many of them which our forefathers observed, those which I liked; and many of those which I did not like I rejected with the advice of councillors, and ordered them to be differently observed. For I dared not presume to set in writing at all many of my own. Because it was unknown to me what would please those who would come after us. But those which I found, which seemed to me most just, either in the time of my kinseman, King Ine, or of Offa, king of the Mercians or of Ethelbert (King Aethelbert of Kent), who first among the English received baptism, I collected herein, and omitted others. Then I, Alfred, king of the West Saxons, showed these to all my councillors, and they said that they were pleased to observe them.

Alfred was keenly interested in the concept of justice and instructed his people: “What ye will that other men should not do to you, that do ye not to other men.”

He mandated impartiality (equal justice under the law) in the moots (courts):

Doom very evenly. Do not doom one doom to the rich; another to the poor. Nor doom one doom to your friend; another to your foe.

(Note that the word “doom” had two meanings—the first referred to a code of law and the second to the judgments of courts).

Despite the self-deprecating language of his prologue, Alfred codified “all legal practice throughout the English Realm” (Tucker). Alfred’s Dooms of 893, together with those of his successors, meld mosaic and customary law, and are concerned with nation‑building and the centralization of power. Alfred introduces the concept of a single Anglo-Saxon people under the rule of a single monarch and laid the groundwork for the development in later times of a kingdom encompassing of all of England.

The Dooms of Edward the Elder (871‑924 AD)

Alfred’s son, Edward the Elder, continued his father’s resistance against the Vikings and won victories in both the Midlands and East Anglia in 917. The following year, following the death of his sister, Aethelflaed, Edward added Mercia to his kingdom. Edward’s reign is significant because he ensured that a uniform set of laws applied in Anglo-Saxon England and mandated that “‘every man’ was able to obtain ‘the benefit of public law, and that every suit shall have a day assigned to it on which it shall be heard and decided’” (Tucker). The Dooms of Edward, issued in between 900 and 925, commence with the statement: King Edward commands all the reeves [sheriffs]: that you judge such just dooms as you know to be most righteous, and as in the doom‑book stands. Fear not on any account to pronounce folkright; and that every suit have a term when it shall be brought forward, that you then may pronounce. The Dooms specified that the reeves hold folk‑moots [courts] every four weeks and, in an expansion of the law of contract, require that purchases made in port take place in the presence of a reeve. These developments mark a further move to a more centralized government and greater administrative reliance on the Anglo-Saxon nobility. On a separate note, these Dooms are interesting in that they contain a rare mention of the medieval “ordeal,” and require that those who have been found to be perjurers “afterwards should not be oath‑worthy, but ordeal‑worthy” (Tucker)

The Dooms of Athelstan (894-939 AD)

Athelstan was King of the Anglo‑Saxons between 924–927 and ruled as King of the English from 927–939. Four codes issued during the reign of Athelstan survive. One Doom is ecclesiastical and relates to the payment of tithes. Another, known as the Ordinance on Charities, is believed to be the first piece of social legislation in Anglo‑Saxon England and provides for direct monetary relief to the poor (Tucker). The two other codes had their origin in the assemblies at Grately and Exeter–the first, known as II Æthelstan, focuses on theft, corruption and lawlessness in the realm and the second, the Exeter code, V Æthelstan, urges compliance with the earlier code and includes an additional provision dealing with the relocation of those who breach the king’s peace but are sufficiently rich and powerful to be able to evade justice. Reflecting a problem in the society of the time, this code contains a provision relating to cattle-tracking.

Athelstan is believed to have established the “shires,” each centered on a burgh (town) or important royal estate, to facilitate the collection of dues payable to the king through the office of the reeve (sheriff). Athelstan regulated the weight of the silver in the kingdom’s currency indicating the increasing importance of commerce.

The Dooms of Edmund (921–946 AD)

Edmund, King of England from 939‑946, convened a synod at London and issued Dooms addressing matters of clerical celibacy, church dues and alms, and restoration of church buildings. Edmund’s second Domes are secular and seek to eliminate blood feuds by offering the kinsmen the option to abandon a killer. These Dooms also provide for the betrothal of maidens and women.

The Dooms of Edgar 959‑975 A.D.

Four of Edgar’s Dooms survive. One was ecclesiastical but the other three focused on the hundred-moot (court). A hundred was the basic form of local government and each shire typically contained ten to twelve hundreds. Edgar’s domes required that the hundred moot meet every four weeks, the borough-moot three times yearly and the shire-moot twice yearly (Tucker). Edgar mandated: “in the hundred, as in any other court, it is our will that in every suit the common law be enjoined, and a day appointed when it shall be carried out.” Edgar maintained that every man, whether poor or rich, was entitled to the benefit of the common law and if justice was not so provided, the plaintiff could “apply directly to the king for alleviation.”(Tucker).

SOURCES:

Charles E. Tucker, Jr. Anglo-Saxon Law: Its Development and Impact on the English Legal System. 2 USAFA Journal of Legal Studies 127 (1991).

Levi Roach. Law codes and legal norms in later Anglo‑Saxon England. Historical Research. Aug 2013, Vol. 86 Issue 233, pp. 465‑486.

Frederick Pollock (Sir), Frederic William Maitland. The History of English Law, Volume I

Dorothy Whitelock. English Historical Documents, 500‑1042 (1955).

University of London, Institute of Historical Research. Early English Laws Project. http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/i-atr/