This blog article was written by Mary Noé, a lawyer and professor in the undergraduate Legal Studies program at St. John’s University and editor of The Legal Apprentice, a showcase for student writing. Ms. Noé talks more extensively about the Harry Kendall Thaw case in the article “Murder At Madison Square Garden: A Dream Team’s Insane Game of Judicial Cat and Mouse” from Issue 18 of the Historical Society of the New York Courts’ Judicial Notice publication, a journal of articles of historical substance and scholarship that uniquely focuses on New York legal history. Be on the lookout later this week when we publish a podcast episode where host Eric van der Vort, Ph.D. speaks about this case with Mary Noé herself!

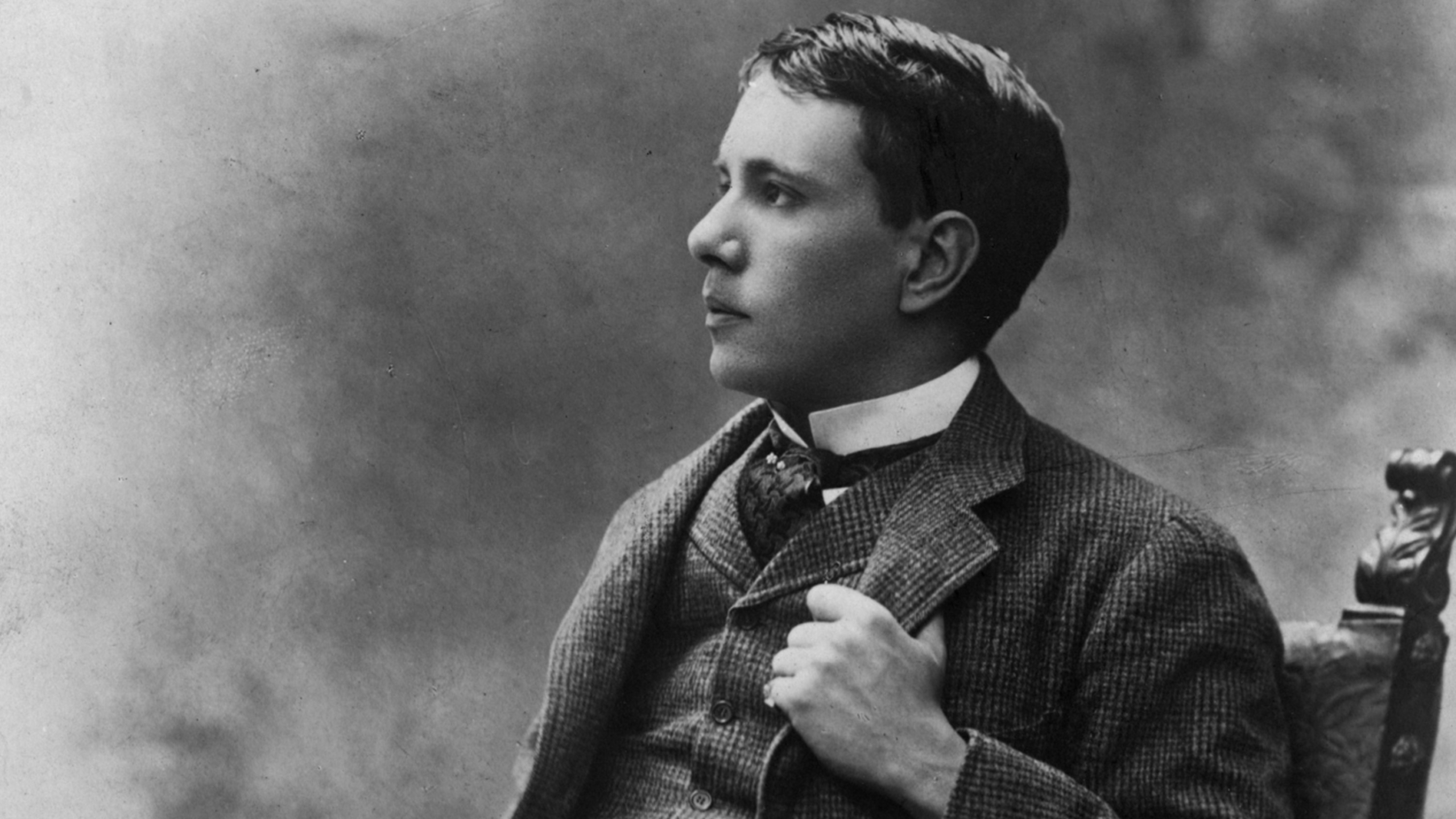

Harry Kendall Thaw, one of the wealthiest men in America, had a problem: if a jury found him guilty of murder, he would die in the electric chair at Sing Sing. It seemed like an open and shut case. Six months before his trial and in the presence of hundreds of people, Thaw shot the renowned architect Stanford White twice in the face and once in the shoulder with his 22-caliber gun in the presence of hundreds of people. White was watching the musical comedy Mamzelle Champagne on the rooftop of Madison Square Garden, a building he designed. At the heart of this tragedy is a girl, Evelyn Nesbit, and her chastity.

Presiding at Thaw’s trial was New York Justice Thomas W. Fitzgerald, who five months before was held in contempt for failure to respond to his debtors in court. The lead prosecutor was William Travers Jerome, a foe of Tammany Hall and a remote cousin of Winston Churchill. Harry Thaw’s dream team was led by Delphin Delmas, known as the “Napoleon of the California Bar” along with attorneys John Gleason, Clifford Hartridge, Daniel O’Reilly, Henry McPike, and A. Russell Peabody.

Delmas posited a diagnosis of “dementia Americana” defined as a “species of insanity which makes every home sacred. . . and whoever stains the virtue [of a man’s wife] has forfeited the protection of human law.”

The jury deadlocked.

Judge Fitzgerald was removed from the bench and the attorneys eventually suffered misfortunes, including disbarment, incarceration and death.

Next up was attorney Martin Littleton, a rail splitter from Texas. He advanced a more traditional defense, not guilty by reason of insanity. The jury unanimously agreed with the defense.

Justice Victor Dowling committed the defendant to Matteawan State Hospital for the Criminally Insane. Before the ink dried on the judge’s order, Thaw’s attorney filed a writ of habeas corpus requesting a hearing to determine Thaw’s current sanity.

For the next eight years Thaw’s legal exploits would continue in three different states, two countries, and include Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes of the U.S. Supreme Court.