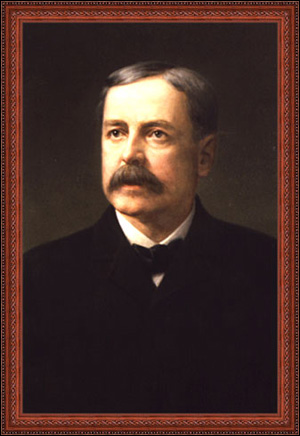

Though his tenure on the Court of Appeals was brief, Judge Samuel Hand’s place in the history of the law of New York State and of the United States is secure, both as a member of one of the leading legal families in the nation, and as the leading advocate before the Court of Appeals in his own time. One observer noted that he was “probably the most successful practitioner who ever appeared before the Court of Appeals,” and another said that, “in very few of the really important cases before the Court of Appeals, has Judge Hand not appeared on one side or the other.”1

Samuel Hand was born in Elizabethtown, Essex County, New York on May 1, 1834 to Judge Augustus Cinncinatus Hand and Marcia Seeyle Northrop. The Hands came to Long Island, New York from Kent, England in 1644, when John Hand helped found what is now Montauk after purchasing 500 acres of land from the Indians. The Hands moved to Lake Champlain in the late 18th Century, settling in Shoreham, Vermont. Augustus and Marcia (of Shoreham), moved to New York State, eventually settling in a wood frame house in Elizabethtown, to which was added a brick house, situated next to Augustus’ law office.2

Augustus Hand was appointed Surrogate of Essex County in 1831, practiced law for 47 years, and served as a Democratic-Republican (as the Democrats were then known) Congressman from 1839 to 1841, a State Senator from 1845 to 1848, and a Justice of the Supreme Court from 1848 to 1855. He served ex-officio on the Court of Appeals in 1855. His legacy, other than his five children – Clifford, Samuel, Ellen, Marcia, and Richard – is that he was primarily responsible for introducing the provision in the New York Constitution of 1846 that made New York’s judges elected, rather than appointed.

As a boy, Samuel entered Middlebury College in Vermont and, after two years, when the faculty of Middlebury was nearly dissolved, he moved to Union College, where he was a member of the Philomathean Society and the Chi Psi fraternity. He was graduated in 1851, the youngest member of his class. More than thirty years later, after a superlative career, Judge Hand was awarded an honorary L.L.D. from Union College in 1884.

After graduation, Hand studied law in his father’s office in Elizabethtown. Following his admission to the bar, he became Justice’s clerk to his father. In 1853 he married Lydia Learned, daughter of Billings P. Learned, and had two children, Lydia Marcia Hand and Billings Learned Hand (the noted jurist who would come to be known as Learned Hand).

Judge Hand’s career in Albany began in 1859, when he entered into a partnership with the former Chancellor John V.L. Pruyn. In 1860, Pruyn retired, and Hand became a junior partner of the firm of Cagger, Porter & Hand in 1861, which was said to be one of the best known, if not the leading firm in the State. Upon Porter’s elevation to the bench in 1865, the firm was changed to Cagger & Hand. Cagger was accidentally killed, leading to the welcome of Matthew Hale to the firm in 1869, and later Nathan Schwartz and Charles S. Fairchild joined.

At the end of Judge Hand’s career it was said that he argued one-third of all cases in the Court of Appeals, and no name appeared as frequently as his in the list of counsel in the Court’s reports.3 The Albany Law Journal described Judge Hand’s style:

[Judge Hand’s] arguments were rarely remarkable on the surface in any sense. They were not marked by wit or humor, nor by fertility of illustration, nor conveyed in the medium of graceful or commanding oratory; but whatever could be done for a client by ample learning, exceptional experience, patient research, a very extraordinary memory, extensive reading, calm consideration, sound forecast, a serious sarcasm, a grave and earnest delivery, and the influence of a pure and dignified character, was uniformly accomplished, and it is probable that no other counselor of his age ever argued so many important causes with so much credit to himself and so much advantage to his clients.4

Hand’s public service began in earnest when he was appointed Corporation Counsel of Albany in 1863. In 1869, he was appointed to serve as the official reporter of the Court of Appeals, the twelfth official reporter of the State. Hand was the Reporter from 1869 until 1872. His service as Reporter coincided with the changes to the State’s judiciary brought about in the Constitutional Convention held in 1867 and 1868 that created the new Court of Appeals in the Constitution adopted in 1869, which took effect on January 1, 1870. The convention had been concerned that the new Court of Appeals should have a fresh start, so it assumed jurisdiction of appeals taken after January 1, 1870. The convention created the five-member Commission of Appeals to decided those appeals taken before January 1, 1870, which numbered some 800 cases. The Commission, with responsibility for those 800 cases left on the old Court of Appeals’ docket, was coequal to the new Court of Appeals. As one commentator has noted, “[t]he bar was met with the puzzling problem of the relative stature of the two parallel highest judicial bodies in event of conflict.”5 Hand, then serving as reporter, resolved problems with publication that arose out of these parallel bodies.

In 1875, Hand was made a member of the Commission on the Reform of Municipal Government, of which Senator William M. Evarts was chairman. The other members of the Commission were William Allen Butler, James C. Carter, Simon Sterne, Joshua Van Cott, John A. Lott, Henry F. Dimock, E.L. Godkin (editor of The Nation), and Oswald Ottendorfer. The Commission produced a report, which was submitted to the legislature in 1877, recommending that the legislature and cities of New York be separated to the extent possible. This was to be established by concentrating executive power in mayors and transferring legislative power to locally elected boards of aldermen, though powers of finance and taxation were to be deposited in boards of finance elected by tax and rent payers. The zeal for reform that caused the Commission to be formed dissipated and the reforms recommended by them were only adopted in piecemeal fashion, if at all.

In 1876, Governor Samuel Tilden, a close political and personal friend of Hand’s, then running for President of the United States, desired that Hand be nominated as a candidate for governor in New York State at the Democratic convention, but it was said that his participation as counsel for the Canal Commission in the prosecution of the canal ring prevented Hand’s nomination.6 Hand had helped expose a group of legislators and businessmen who were amassing fortunes upon fraudulent bills for the repair of New York’s canals. Hand refused to have his name presented for nomination in the face of the opposition engendered by his participation in this anti-corruption effort. Lucius Robinson took the nomination, instead, and became governor.

In June of 1878, Governor Robinson appointed Judge Hand to fill the vacancy on the Court of Appeals occasioned by the death of Associate Judge William F. Allen. Judge Hand served on the Court for the second half of 1878, penning nearly twenty unanimous opinions, before returning to private practice upon the election of Judge Danforth.

Succeeding former Court of Appeals Judge John K. Porter, in 1878 Judge Hand became the second president of the recently formed state bar association, serving for two terms. Previously he served as the association’s vice-president. In his presidential address to the association delivered at the third annual meeting held on November 18, 1879, Judge Hand argued for the association to dedicate itself to the policing of the legal profession. In his words, “To make itself the guardian of, and to take upon itself the duty of, preserving order in our ranks, I think to be its most important purpose.” His address makes clear that he was intent on protecting the legal profession from unethical and incompetent practitioners because he believed so strongly in the worth of a career in the law:

Let me say, in conclusion; to me, it seems, that to be conversant with the laws and to be engaged in interpreting them and applying them to the exigencies of human affairs, is not only, morally, a permissible career, but, perhaps, the highest, the noblest secular pursuit, in which man can be employed. So far from tending to deteriorate the moral tone, it intensifies every feeling for, and renders acute every sense of, righteousness, of equity and of uprightness.

The seriousness with which Judge Hand approached his position in society as a lawyer is reflected in the contributions he made as an adviser to both Governor Grover Cleveland, who was said to have relied on Judge Hand’s legal advice implicitly, particularly in the Governor’s veto of the bill reducing fares on the New York elevated trains (which is thought to have cost Cleveland many votes when he ran for President), and Governor Tilden, and as counsel for New York in the case against J.J. Belden, in which he secured a $400,000 judgment for the State from the referee, and in the Navarro water meter suit.

Apart from his activities in government and at the bar, Judge Hand served as a director of the Union National Bank of Albany, and governor of the Fort Orange Club. Also, in addition to the volumes one through six of the New York Reports, published in 1869, 1870 and 1871, when Hand served as reporter of the Court of Appeals, Hand published the Philobiblon of DeBury, edited with notes and translations in 1861. He was a great lover of literature and music, was a scholar of modern languages, and possessed what some considered the finest private library in Albany.

Judge Hand died quite suddenly. In early May 1886, afflicted with cancer of the tongue, he wound down all of his professional responsibilities after the close of the Court of Appeals’ term on April 30. At the time of his death he was serving as president of the Special Water Commission for Albany. Judge Hand died at his home in Albany on May 21, 1886. In observation of his passing the Circuit Court in Albany adjourned. He was survived by his wife, son, and daughter.

Progeny

Jonathan Hand Churchill and Robert Monroe Ferguson, both retired attorneys of Manhattan, are descendants of Judge Hand by way of their grandfather, Learned Hand, Judge Samuel Hand’s son. Other descendants of Judge Hand in Mr. Churchill’s generation include Phyllis Ferguson Seidel, Patricia Ferguson Doar, Professor Constance Jordan, and Fan Morris. Arthur V. Savage of Manhattan, New York, a retired attorney, is a great-nephew of Samuel Hand’s brother Richard and a grandson of Judge Augustus Hand. Constance Morris, the late Mary Hand Darrell, and Frances Ferguson are granddaughters of Judge Samuel Hand. These individuals have children and grandchildren of their own.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Albany Law Journal, May 29, 1886.

Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, Columbia University Press,

1985, pp. 114-119.

Gunther, Learned Hand: The Man and the Judge, Alfred A. Knopf (1994).

Hand, Letters of the Hand Family 1796-1912, Edwin S. Gorham (1923).

The Hand House and Law Office, Bruce L. Crary Foundation.

The Hands, A distinguished family of American Jurists, Middlebury College Newsletter,

Autumn 1972, pp.81-87.

History of the Bench and Bar of New York, Vol. 1, pp. 352-353, New York History Co., 1897.

Martin, Causes and Conflicts: The Centennial History of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York 1870-1970, Fordham University Press (1997).

Nelson, The Remarkable Hands: An Affectionate Portrait, Foundation of the Federal Bar Council Proceedings on Announcement of the Death of Hon. Samuel Hand, 102 NY 743 (1886).

The Purple and Gold, Chi Psi, Vol. 4, pp. 17-18.

Samuel Hand, The New York Times, May 22, 1886.

Spivey, “But how are their decisions to be known?” New York State Law Reporting Bureau

(2004) p. 29.

The State Campaign, The New York Times, October 6, 1875.

Published Writings Include:

Samuel Hand, “The Death Penalty,” North American Review 133 (December 1881), 541-550;

reprinted in Selected Articles on Capital Punishment, Compiled by Lamar T. Beman (New York: H.W. Wilson Company, 1925), 178.

De Bury, Philobiblon, A Treatise on the Love of Books, By Richard De Bury, Bishop of

Durham, and Lord Chancellor of England. First American Edition, with The Literal

English Translation of John B. Inglis, Collated and Corrected with Notes by Samuel Hand.

Endnotes

- The Purple and Gold, Chi Psi, Vol. 4, pp. 17-18.

- The Hand House and Law Office on River Street, Elizabethtown, New York is currently owned and maintained by the Bruce L. Crary Foundation and can be visited by appointment.

- Albany Law Journal, May 29, 1886, p. 421; however, an electronic database search of appearances by Samuel Hand at the Court of Appeals and the cases decided by the Court between 1859 and 1887 reveals that Hand appeared in approximately 8% of the Court’s cases in that period, nearly 800 appeals, a truly astonishing and very likely unrivaled amount.

- Albany Law Journal, May 29, 1886, p. 421.

- Bergan, The History of the New York Court of Appeals, 1847-1932, Columbia University Press, 1985, p. 117.

- Samuel Hand, The New York Times, May 22, 1886; The State Campaign, The New York Times, October 6, 1875.