Edward R. Dudley was the first Administrative Judge for Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County under the Unified Court System. Judge Dudley was not one to seek publicity for himself and so his story may not have been fully known during his tenure as Administrative Judge nor since. But, as we shall see, he had a very varied, colorful, interesting, and productive life, a good part of which was spent in service to his country and the State and City of New York.

Judge Dudley’s family came from North Carolina. He was born in 1911 in South Boston, Virginia. His father was a dentist and his mother a teacher. He went to grammar school in Roanoke, Virginia. As a student, the future Judge worked at various odd jobs, including bellhop and waiter. He received a Bachelor’s degree from Johnson C. Smith College in Charlotte, North Carolina in 1932. He taught for a time in a one-room school in Virginia. He taught seven grades and even drove the school bus, all for the munificent salary of $ 80 a month. He enjoyed teaching and would probably have made it his career, he said, but for the fact that he received a scholarship to go to dental school at Howard University. He moved to Washington, D.C., to which he would later return often in his career. Following his father’s path, he enrolled in the dentistry program at Howard and studied that subject for a year. He concluded, how- ever, that dentistry was not for him and withdrew from school.

In order not to burden his family (his mother had died when he was but seven years old), he moved to New York City, “bright, fresh and full of vinegar,” as he put it many years later. Arriving in New York at a young age, as he did, he must have admired the “big City,” but, coming from a rural background, he may have been concerned too about the challenges it presented. Chance plays a very significant part in everyone’s life and it did in his, both then and later, but he overcame whatever trepidations he may have had about the uncertainty that lay before him. In New York, despite the economic problems of the time, his life and career were to flourish.

In New York, Judge Dudley became close to his uncle on his mother’s side, Edward A. John- son, who, born in 1860, was a real estate developer active in local New York City politics (at one point he was a state assemblyman). The Judge worked for a while in his uncle’s real estate office as a clerk. At this time, his uncle was in his 70’s and was going blind, so the Judge spent many hours reading to him.

The Judge again worked at various jobs to defray his expenses. One of those was in a WPA public works theater project, the Federal Theater at the Lafayette Theater. There he was an assistant stage manager. Dooley Wilson of “Casablanca” fame was one of the actors who appeared on his stage. He also worked for Orson Welles, who wrote and directed an adaptation of “Macbeth” for the theater. This production was a great success, playing in various theaters around New York and touring, to Dallas, Chicago, Detroit, and elsewhere around the country.

Judge Dudley greatly enjoyed his work in the theater, but after some years he concluded that the career prospects for him in that field were few. Although he never mentioned the matter to us, but for the racism of the day, he might have hoped for a career as an actor. He was highly intelligent, very articulate, and blessed with a deep baritone voice, a tall, athletic, self-assured presence, very good looks, and powerful personal magnetism, all of which would have commended for him a career on the stage. But he chose another path, one in which, as things turned out, those gifts would serve him well. In 1939, he went to St. John’s University School of Law. For a period, he worked in the theater at night and went to law school during the day. He took classes in the summer as well and so was able to complete his studies earlier than would otherwise have been the case. While there, he was a member of the Law Review. In 1941, he graduated with an LL.B. and passed the Bar the same year. He was admitted to practice in New York on December 8, 1941.

Judge Dudley went to work at the Pepsi Cola Company. Shortly thereafter, he was recruited by Thurgood Marshall, then Chief Counsel of the Legal Defense and Education Fund of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), to become a Special Assistant Counsel at the Fund. In this period, before Brown v. Board of Education, the Judge worked on cases and wrote briefs seeking the admission of black students to colleges in the south, equal pay for black teachers, such as he had once been, and non-discriminatory public transportation. He also worked on voting rights cases. The NAACP developed a network of lawyers around the country who were willing to work on these cases. “[W]hen we got a case throughout the United States,” Judge Dudley said many years later, “we would call on these lawyers who were strategically placed, asked their help and they would give it. And this was the way we were able to handle far more than the number of cases that our office could handle itself.”

In the days before Brown, it was necessary to defend and advance the rights of the clients aggressively, but at the same time with judiciousness and care. Mr. Marshall was painfully aware that bringing a certain kind of challenge too early, before all the conditions for progress were ripe, could set the civil rights movement back 50 years.*

One case Judge Dudley tried concerned a challenge brought on behalf of the custodian of a separate black school who was receiving an annual salary of $ 1,500 while the person who filled the exact same position at a “separate but equal” school for whites received $ 3,000 per year. This case and others like it must have resonated deeply with the Judge given his background as a one-time teacher in Virginia. Individual cases, fact-specific challenges such as this, helped to lay the foundation for Brown and the progress that was to follow it.

When Judge Dudley first went to work with Mr. Marshall, they two were the entire complement of the legal staff at the Fund. The hours were long, the financial compensation modest, and the work was not without its dangers. Mr. Marshall has, of course, been heralded for his pioneering representations, and very properly so. As an important, very early member of Mr. Marshall’s team, Judge Dudley, too, is deserving of much credit for work that changed the country. That experience during his formative years as a lawyer must have exerted a considerable influence throughout Judge Dudley’s professional and personal life. Of course, afterward, others joined the staff of the NAACP Legal Defense and Education Fund, including Constance Baker Motley, Robert Carter, and Franklin Williams, and, later still, a young O. Peter Sherwood, who himself now graces our bench as a Justice of our Commercial Division.

On some issues, the Fund sought to achieve its objectives through voluntary concessions by adversaries. In many other instances, though, formal legal action was necessary. “Most of our other problems at that time we took to court,” Judge Dudley remembered, “and we were very successful in many of the suits that we brought.” Traveling in the South and representing the clients they did was perilous work. Often the team would find accommodations in the homes of local black residents. One such family who put up the team in Georgia was that of William Hunter, who later followed the team back to New York City. Bill remained close friends with Justice Marshall for all of the years following and visited Justice Marshall in the latter’s home and later in his chambers at the United States Supreme Court. In time, Bill joined our court as Judge Dudley’s Administrative Aide. Bill had countless friends and admirers throughout our court and beyond.

After some years of work at the Fund, Judge Dudley’s career changed course again. The Governor of the Virgin Islands spoke to the Mayor of the City of New York, William O’Dwyer, about finding an attorney to assist him. Mayor O’Dwyer in turn spoke about the appointment with the head of the NAACP, Walter White, who approached Judge Dudley to see if he would be interested in the position. In 1945, Judge Dudley became the Legal Counsel to the Governor of the United States Virgin Islands. One of the Governors he served was William Hastie, the first African-American appointed Governor of a United States territory and later a distinguished Federal judge.

Judge Dudley married in January 1942. He was very blessed in his marriage. His wife, Rae Oley, was a formidable figure in her own right as a career educator and teacher and a loyal life partner to the Judge in all things. Rae Dudley had her own circle among educators and others, and Judge Dud- ley would from time to time mention her lifetime friendships among her college “sorority sisters.”

In 1948, things changed yet again and Judge Dudley became the beneficiary of a piece of extraordinary good fortune. He returned to the United States with his wife because they needed to put their son in school. In that year, the then-United States Minister to Liberia gave up his post and re- turned home “because,” in Judge Dudley’s words, the Minister “was sure that the Democrats were going to lose that year and that Thomas E. Dewey would become the next President of the United States.” Judge Dudley’s son believes that President Truman put together a panel to search for a qualified African-American to serve in Liberia if he won the election. The panel recommended Ralph Bunche, who declined. At some point, Thurgood Marshall was recommended, but he was unable to go because of his commitment to the civil rights struggle in the courts of the United States. Mr. Marshall suggested Judge Dudley for the post.

In addition, Judge Dudley recounted, the State Department looked for a replacement and approached Walter White and some others in New York City seeking possible candidates. The Judge was asked whether he would be willing to take the now-empty position if offered. He believed that his experience in the Virgin Islands had been one of the things that may have led to this inquiry. He agreed to go home and talk to his wife about the idea, which he did. “I told her that we’d never been many places and,” thinking much like his predecessor, “it looked as though the job would be over by the end of the year.” They agreed to go, assuming that “we’d go over that summer and be home by Christmas.” But things turned out differently, of course, and he and his wife stayed five years.

President Truman appointed him United States Envoy Extraordinary and Minister Plenipotentiary to Liberia. As Judge Dudley, his wife, and their son, Edward R. Jr., got off the boat on a very bright and beautiful morning in Liberia, they were approached by a stevedore. This man said, “Mrs. Dudley, I think you used to teach me in school.” So “they had a big laugh about that,” which of course made the world for a moment seem a small place.

Invitation to the Dudleys from President Tubman and his wife.Judge Dudley’s son reports that President Truman was concerned at that time about the danger of communism finding a foothold in Africa. The President decided to raise the status of the United States mission in Liberia to the same as it was in Europe, an embassy led by a United States Ambassador. The President wanted to show the Africans that, despite the well-known lack of freedom for all in the South of our country, America was the world’s leading proponent and defender of freedom for all. Thus, in May of 1949, the U.S. Mission in Liberia was raised to the status of an Embassy and Judge Dudley became the United States Ambassador. He was not only the first United States Ambassador to that country, but the first African-American to serve as an Ambassador for the United States of America anywhere in the world.

During his years as Ambassador, Judge Dudley carried out the regular diplomatic duties that go with that office, becoming in time the dean of the diplomatic corps there. He also worked extensively to advance President Truman’s agenda, in particular, the Point Four Program, which the President had announced in his inaugural address in January 1949. The Program endeavored to provide aid, including technical assistance, equipment, and training, for Africa and other developing areas of the world. In Liberia, the United States sought to provide aid and assistance under the Program in four areas: agriculture, education, public health, and engineering. There were over a hundred persons from the United States working on the Point Four Program in Liberia, many of them experts in the four areas covered. The Program placed much emphasis on technical assistance and training for the Liberians in the areas of specialization of the Program’s experts. In addition, of course, Ambassador Dudley was in charge of the normal Embassy staff.

During Judge Dudley’s time there, the United States provided assistance to introduce new methods for the improved cultivation of rice. In the area of engineering, much work was done on sanitation and, in particular, mosquito control. Roads and other infrastructure were built. In education, many schools were established, including schools for the training of nurses, which proved to be very important and beneficial for Liberia for many years afterward.

Ambassador Dudley sought to promote good commercial relations and opportunities for the United States. He also sought to advance a productive and mutually beneficial relationship between Liberia and the United States. To do this, he met very frequently, on a weekly basis and more often if needed, with the President of Liberia, William Tubman, and together with him worked to address areas of mutual concern.

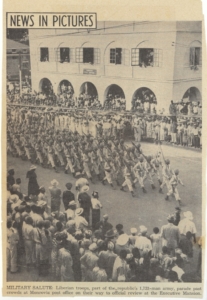

At one point, President Tubman suggested that the United States send a small military mission to train the Liberian military, which had been having serious difficulties controlling the country’s borders. Ambassador Dudley made a request through State Department channels that such a mission be dispatched for this limited purpose. After the request was made, however, nothing happened. So, on a later trip back home, Ambassador Dudley went to the White House and saw President Truman. He argued in favor of such a narrow mission. The President got up from his desk and walked about the room with his hands in his pockets. Then he said, “I don’t see why you don’t have it.” He added, “I’m going to send a memorandum to the State Department tomorrow.” He did so, and the small training mission became a reality.

After Judge Dudley arrived in Liberia, he discovered a problem. The leading black Foreign Service Officer in the country had never had the opportunity to serve in any other post anywhere in the world. This was the case despite the fact that the policy of the State Department was to rotate Foreign Service Officers among different countries every few years, in order that the Officer might become a better prepared and more fully-rounded diplomat and might also have an improved chance to move up the career ladder within the Service. Ambassador Dudley looked into the matter further. He found out that African-Americans had been sent to Liberia and some other countries, certain hardship posts, but not elsewhere. Both black Foreign Service Officers and other black officials and employees of the United States Government who were sent to Africa ended up in these few countries only. This situation, he learned, had been going on for many years. One Foreign Service Officer he encountered at Monrovia had been there ten years. Another fellow had just left after a long tour to go to one of the other hardship posts and his brother was still there. The Judge was told that a woman who had been reassigned had been in Liberia for almost 25 years, and another for 17.

Spurred by this information, the Ambassador undertook, with the aid of staff, thorough research into the question. He prepared a memorandum that identified every black diplomat in the Foreign Service over a long period; when they had entered the Service and how long they had been in; where they were serving; and whether they had been reassigned to other posts. Similar information was collected on other Foreign Service Officers who joined the Service at the same times. The data con- firmed the information Ambassador Dudley had initially acquired: African-American Foreign Service Officers were sent to hard- ship posts in a limited group of countries, the “black circuit,” in the words of the Judge’s son, and did not receive the kinds of reassignments they should have had under State Department policy, which obviously stunted their careers. Other Foreign Service Officers of similar age received multiple assignments every few years and were not confined to hardship posts. “[I]t didn’t take,” Judge Dudley said years later, “a Philadelphia lawyer to tell me that something was wrong ….”

On one of his regular trips to Washington, Ambassador Dudley asked for and received a meeting with the Under Secretary of State. He explained to the latter the problem he had uncovered and gave him a copy of his memorandum. The Under Secretary read the memo in the Ambassador’s presence. Visibly disturbed, he suggested that the Ambassador leave the memorandum with him, which Judge Dudley was glad to do.

On one of his regular trips to Washington, Ambassador Dudley asked for and received a meeting with the Under Secretary of State. He explained to the latter the problem he had uncovered and gave him a copy of his memorandum. The Under Secretary read the memo in the Ambassador’s presence. Visibly disturbed, he suggested that the Ambassador leave the memorandum with him, which Judge Dudley was glad to do.

Ambassador Dudley returned to Liberia in the normal course and resumed his work. Within six months, transfers began to come through. The leading African-American Foreign Service Officer in Liberia was reassigned to Paris, the first time that had ever occurred anywhere in Europe. A second officer was sent to Zurich and a third to Rome. The State Department even moved the Ambassador’s code clerk and sent him to London.

Speaking later about these events, Ambassador Dudley was pleased with the outcome of his work on this project. “We think we opened the door and stopped this kind of discrimination.” Judge Dudley said nothing, however, about the impact of his advocacy on his own career. His son believes that, despite the success of his efforts to change assignment policies, this advocacy damaged his father’s career within the State Department.

After the Eisenhower Administration took office, Ambassador Dudley stayed on in Liberia for seven months. Then he decided to return home, primarily so that his son might be able to take ad- vantage of the better schooling available in the United States. But the Ambassador was also motivated by a dawning conviction that the new administration was overemphasizing a strategic approach to foreign policy and was taking a “shortsighted” view of the utility, to the world but also to the United States, of aid efforts such as the Point Four Program.

Ambassador Dudley returned to the United States in 1953. On his return, he went to the White House and met with President Eisenhower and gave him his views on the issues facing the United States abroad. A few days later, the Ambassador reentered private life and returned to the practice of law.

Once again, he worked with the NAACP in its efforts to promote racial justice through legal challenges to discriminatory practices, this time raising funds to support the organization’s work as the head of its Freedom Fund.

In 1955, he received his first judicial appointment. Mayor Robert F. Wagner called him down to City Hall and asked whether he would like to be a judge on the Family Court. He agreed and served there until 1960. In that year, when the Manhattan Borough President resigned, Judge Dudley was appointed by Mayor Wagner to fill out the term. He won election to that position after a highly contested primary and served until the end of 1964. He made moderate-cost housing a priority in an effort to keep housing in the City affordable for the middle class, which remains among the most critical issues confronting the City to this day. In this period, he was also the chair of the New York County Democratic Committee.

In 1962, he was the Democratic-Liberal candidate for Attorney General of New York State, but was defeated by the very well-known and popular incumbent, Louis J. Lefkowitz. Judge Dudley was the first African-American to run for statewide office in New York on the ticket of a major party.

In 1964, he won election to the New York State Supreme Court, where he was to serve until 1985. In 1967, after Mayor Lindsay and the Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division had come to see him to pose the idea, Judge Dudley was named Administrative Judge of the New York City Criminal Court. He was probably the first African-American to serve as an Administrative Judge in New York State. During his years in that position, he reorganized the operations of the court.

In 1970, he was designated the Administrative Judge of the Supreme Court for Manhattan and the Bronx, Civil and Criminal Terms. The Twelfth Judicial District, consisting of Bronx County, had yet to be created, so at that time Bronx County was part of the First Judicial District along with New York County. Because of the increase in crime in the City in these years, the business of the criminal side of Supreme Court grew and so, in 1972, separate Criminal and Civil Branches of Supreme Court were established in the First Department. Judge Dudley remained as the Administrative Judge of Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York and Bronx Counties. In 1976, Judge Dudley, while continuing to serve as Administrative Judge, became the Presiding Justice of the Appellate Term.

Mrs. Dudley was also busy. Among other things, in the 1960’s, she joined a group called “Wednesdays in Mississippi.” This group, founded by Dorothy Height and Polly S. Cowan of the National Council of Negro Women, brought middle-class women of the north, including Mrs. Dudley, to Mississippi to support the struggle for civil rights there. The participants, who were black and white and of many religious faiths, traveled weekly to the South in the summer, beginning in the “Freedom Summer” of 1964. They met with civil rights activists and African-American professional women to build bridges and lend support, worked to register voters, and the like. The work in Mississippi in those years was dangerous. Some years ago, Mrs. Dudley attended a commemorative gathering on the 50th anniversary of the group.

In the 1970’s, she served (salary: one dollar per year) as a member of the Board of Directors of the Henry Street Settlement. Mrs. Dudley was an early collector of art created by African-American artists. A picture she purchased from her friend, painter Norman Lewis, now hangs in the Boston Museum of Fine Arts.

Pursuant to amendment to the New York State Constitution in 1977, the four Appellate Divisions ceded much of their responsibility for administering the New York State trial courts to the newly-created Office of Court Administration, and the New York City Trial Courts were transferred from the New York City budget to the New York State budget, with the judges and staff of these courts becoming employees of the State rather than continuing to be, as they had been, employees of the City. Judge Dudley served as the Administrative Judge of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, Bronx and New York Counties, during this transfer of administrative responsibility over those courts and the transfer of fiscal responsibility for these courts from the City to the State. He remained Administrative Judge until 1982, and served as the Presiding Justice of the Appellate Term until his retirement from the bench in 1985.

In conjunction with all of these changes a reclassification study of all staff titles was undertaken by the Office of Court Administration. This turned out to be in certain respects a very contentious process, with various title series being, in the eyes of their members, “downgraded” significantly. The former presiding justice of the Appellate Division, First Department, Owen McGivern, then in private practice with the firm of Donovan Leisure, together with his colleague at the firm, Paul Crotty, Esq. (later Corporation Counsel of the City of New York and United States District Judge), undertook the representation of the Court Attorneys’ Association of the City of New York and the New York Court Clerks Association in the reclassification appeals process. Those appeals proved quite successful.

During Judge Dudley’s tenure as Administrative Judge he worked closely with then-General Clerk of the Court (now known as the Chief Clerk of the Court) Thomas Galligan. When Mr. Galligan was appointed to the Criminal Court, his successors in that position were Herbert Spector and Max Sirkus, Esq. Max retired toward the end of Judge Dudley’s tenure as Administrative Judge, and was succeeded by Acting Chief Clerk John Jaeger. Jack was succeeded in that position by Jonathan Lippman, Esq. and, later, by John F. Werner, Esq. As Presiding Justice of the Appellate Term, First Department, Judge Dudley worked very closely with the then-Chief Clerk of the Appellate Term, the aforementioned John Werner.

Judge Dudley was much admired by Justices and staff. His leadership qualities were obvious and his broad and significant experience at the Bar and throughout his career, coupled with his natural dignity and dynamism, gave him a gravitas that was highly suitable to that high office in the court. On the bench he was a force to be reckoned with. Judge Dudley’s interests and intellectual pursuits were wide-ranging, but clearly, and much to his credit, he never took himself too seriously and al- ways, as the saying goes, “remembered where he came from,” and he remained entirely committed to fairness and equal opportunity for all. Those wonderful personal qualities endeared him to our Judges and staff, but he was not a sentimentalist, or if he was, it never showed. He largely kept his own counsel and remained true to himself throughout.

Judge Dudley was an accomplished bridge player. He regularly played with a group associated with the court, including his colleague, Judge Aron Steuer, who served as a Justice of the Appel- late Division, First Department, and other judges. Judge Dudley’s son, Edward, was also an avid player and he and his father were regulars in a game (1/2 cent a point) at Judge Steuer’s home for several years.

Upon his retirement in 1985, after more than 25 years of very distinguished judicial service, Judge Dudley eschewed a lavish retirement party, preferring to himself host a luncheon at a restaurant near the courthouse for those judges and mostly staff with whom he had worked most closely. He thought that retirement meant truly turning the page and he said at the time that he would not be re- turning to visit the court, and he did not.

The Judge died in 2005, shortly before his 94th birthday. He was survived by Rae, his wife of 63 years, his son, Edward R., Jr., two brothers, and three grandchildren.

On a number of occasions in the years that followed his father’s retirement, court personnel — a judge or a clerk or a court officer — would stop his son, Edward, himself an attorney, in the halls and tell him that his father had never been too busy to listen to the concerns of that person and to assist him or her with whatever problem lay at hand. The Judge’s son was quite touched by these encounters, which meant much to him and his family.

Edward R. Dudley the diplomat is not forgotten by his country either. In February 2019, a program on five outstandingly influential African-American diplomats, including Ralph Bunche and Judge Dudley, was presented at the U. S. State Department ’s United States Diplomacy Center in Washington, D.C. This program reviewed the diplomatic careers and achievements of the five sub- jects and their contributions to the foreign policy of the United States. The program was aptly titled “African-American Trailblazers in Diplomacy.” Judge Dudley was indeed a trailblazer — in diplomacy, in the struggle to achieve a fairer and more perfect union for all in this country, and in the search for justice for all in the courts.

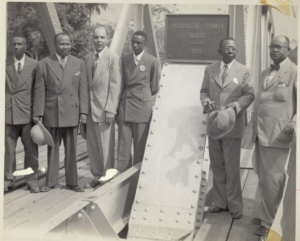

In 2008 a large judicial delegation from Liberia visited 60 Centre Street, including the Chief Judge of the Supreme Court of Liberia, the Honorable Johnnie N. Lewis. On that occasion we contacted Judge Dudley’s son and invited him to join with us in hosting that delegation, and he graciously agreed to do so. Liberia was at that time still recovering from two disastrous civil wars (1989-1996 and 1999-2003). There were several senior members of the delegation who remembered Judge Dud- ley from his years as our Ambassador to their country and others who knew of his ambassadorial service there. Of course in planning their visit they had had no idea that in coming to our court they would find this connection. Judge Dudley’s son brought with him to the gathering some photographs of the Judge taken in the late 1940’s and early 1950’s in Liberia amongst Liberian officials of the day, as well as a photograph of the Dudley family taken during that time. Judge Lewis told us that so many Liberian government records were lost during the civil wars that he would appreciate our sending him copies of those photographs, and we did. Judge Dudley’s good work in service of his country and in aid of the citizens of Liberia continued to exert an influence even after many years, as his dedication to the law and the cause of justice for all and his judicial service continue to do today.

Sources

Obituary, New York Times, Feb. 11, 2005.

The Black Past Remembered and Reclaimed, www.blackpast.org/aah/dudley-edward-richard-1911-2005.

Dudley, Edward R. (1911-2005), Amistad Re- search Center, http://amistadresearchcenter.tulane.edu/archon/?p=creators/creator&id=312

Interview with Hon. Edward R. Dudley, The Association for Diplomatic Studies and Training, Foreign Affairs Oral History Project (Initial Interview, 60 Centre Street, April 3, 1981), available at www.adst.org/OH%20TOCS/ Dudley,%20Edward%20Richard.toc%201981.pdf.

Communications of the authors with Edward R. Dudley, Jr., Esq.

Photographs of Ambassador Dudley with Liberian President William V.S. Tubman are available in the William V.S. Tubman Photograph Collection at Indiana University (http: //purl.dlib.indiana.edu/iudl/lcp/ tubman)

Judge Dudley’s papers covering the period 1942-1973 are located at the Amistad Research Center of Tulane University.

For information on “Wednesdays in Mississippi,” see Debbie Z. Harwell, Wednesdays in Mississippi: Proper Ladies Working for Radical Change, Freedom Summer 1964 (U. Miss. Press 2014); Holly Cowan Shulman, “Wednesdays in Mississippi,” Lilith (Winter 2013-2014).

* See, for example, Rachel Devlin, A Girl Stands at the Door (Basic Books 2018), which describes the calculations of Mr. Marshall and his colleagues as to when, where, and in which factual situations it would be most effective to raise claims aimed at desegregating the schools in the South. The book also tells the tales of the plaintiffs in desegregation cases, many of whom were young girls.

** See https://diplomacy.state.gov/archives/5265