On July 17, 1876, the New York Times reported on the adamant refusal of retired Court of Appeals Judge Addison Gardiner to be considered for nomination as Democratic candidate for Governor. In a letter to the editor of the Rochester Union, Judge Gardiner thrust a “huge stopper” into the trumpet that the Union had been blowing in favor of Judge Gardiner’s nomination. Judge Gardiner explained that, with his resignation of the office of Lieutenant Governor in 1847, he:

left, finally and forever, the field of politics to abler and more adroit men. I have nothing to regret as to the course then taken. A Buffalo editor has said that I was unknown to the present generation. This was intended as a sneer, but is truth, nevertheless. For twenty-five years I have been dead and buried — politically; and now, on the borders of four-score, it is more becoming that I should read and inwardly digest the Collect1 for persons in extremis than to move round with a hat soliciting ballots to be made a candidate. Accept my thanks for your kindness, Mr. Editor, but leave me in peace. I protest solemnly against being exhumed at this time and galvanized into a sort of half life, for any purpose or in the interest of any party. Your friend, A. GARDINER

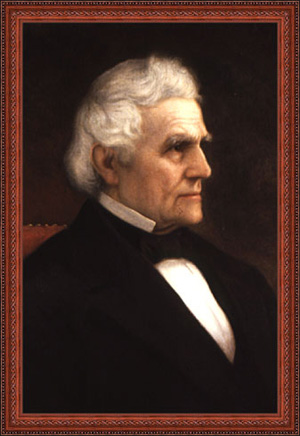

Considering Judge Gardiner’s myriad professional accomplishments and stellar reputation as a jurist, it is not surprising that the Rochester newspaper sought to restore him to the political scene.

Addison Gardiner was born in Rindge, New Hampshire on March 19, 1797, to William Gardner, who served as a colonel of a local regiment and for three years as a member of the state legislature, and Rebecca (Raymond) Gardner. Addison Gardiner was a grandson of Isaac Gardner, of Brookline, Massachusetts, who served as a justice of the peace in colonial times and died in a skirmish in the first days of the Revolutionary War. The family eventually settled in Manlius, Onondaga County, where William Gardner was a successful merchant and manufacturer. His sons, of which Addison was the third, restored the original spelling of the family name, Gardiner. Addison Gardiner received his early education at the Manlius Academy and later entered the senior class of Union College, receiving a degree in 1819. He returned to Manlius to study law and, in 1822, moved to Rochester to commence his practice.

Very soon thereafter, Gardiner became Rochester’s first justice of the peace. He formed a law practice with partner Samuel Lee Selden,2 under the firm name of Gardiner & Selden, and Henry Rogers Selden,3 younger brother of Samuel, read law in their office. The firm was one of the most prominent in Rochester, indeed in all of western New York, and the three men achieved exalted positions in government and the judiciary.

In 1825, Gardiner was appointed district attorney for Monroe County and, in 1829, when Gardiner was not yet 32 years old, Governor Enos T. Throop appointed him circuit judge for the eighth circuit, comprising Allegany, Erie, Chautauqua, Monroe, Genesee and Niagara counties. Within months after his appointment, Judge Gardiner presided over the case of People v. Mather (4 Wendell 229 [1830]), years later recognized as one of “the most memorable trials known in the history of western New York, perhaps in the State” (Proctor, Addison Gardiner, 45 Alb L Journal 7, 10 [1892]). The case arose out of the fierce moral and political controversy between anti-masonry and masonry which then existed and centered on the abduction and suspected murder by masons of William Morgan. Mather was indicted as a conspirator in the abduction and brought to trial before Judge Gardiner. After a 10-day trial – then a remarkable length – Mather was acquitted. The People appealed, seeking a new trial on juror qualification issues, among others, and the Supreme Court affirmed Judge Gardiner on every question. The case was for many years cited as a leading case on conspiracy and juror qualification, and Judge Gardiner’s conduct of the complex, notorious trial helped establish his reputation as a model circuit judge. “[N]o judge ever held the scales of justice so evenly balanced as did Judge Gardiner in this case” (id.).4

After almost nine years, Judge Gardiner resigned his seat and resumed private practice in Rochester. In 1844, on a ticket with Silas Wright for Governor, Addison Gardiner – a “strict construction, hard money, State rights Democrat” (Memorial Address of William F. Cogswell on behalf of the Bar [June 28, 1883], In Memorium, Addison Gardiner [Privately Published], at 26) – was elected Lieutenant Governor of New York State. As such, Gardiner was presiding officer of the Senate and of the Court for the Correction of Errors, consisting of the Senate, the Chancellor and the judges of the Supreme Court. Gardiner was reelected as Lieutenant Governor in 1846, though Governor Wright was defeated by Whig candidate John Young. In his political life, Judge Gardiner was known as a true progressive:

in all departments of human affairs. He strongly favored the simplification of the law in respect to the titles of real estate, and of trusts with its cognate subjects, introduced into the revision of the statutes. He favored the changes by which married women acquired a new status, and by which the antiquated rubbish that her existence before the law was swallowed up in that of her husband, was abrogated. He helped to shape the legislation of the State so as to remove from a dissatisfied and suffering section the last relics of an anomalous semi-feudal tenure which greatly disturbed and threatened danger to the State (id. at 25).

In 1847, Gardiner, along with Greene C. Bronson, Charles H. Ruggles, and Freeborn G. Jewett, was elected to the newly-formed Court of Appeals. Four other judges from among the eight judicial districts would serve one-year terms. In 1852, he was elected a trustee of “the projected Female College at Rochester.”5 Judge Gardiner served as Chief Judge beginning on January 1, 1854 and declined to seek reappointment at the end of his eight-year term in 1855. His old friend and law partner, Samuel L. Selden, succeeded him on the Court, and some speculated that the “suggestions of friendship” influenced Judge Gardiner’s decision to retire when he did. Additionally, Judge Gardiner’s dissatisfaction with the constant fluctuation in the Court make-up contributed to his departure, as the “continual change tended to produce a want of symmetrical, harmonious development of the law by the decisions of the court” (id. at 20). Examples of his writing may be found in his dissent in Danks v. Quackenbush (1 NY 129 [1848]), discussing the constitutionality of an exemption of personal property from execution for antecedent debts, and his opinions in Chautaque Co. Bank v. White (6 NY 236 [1852]), determining the scope of a receiver’s deed, and Talmage v. Pell (7 NY 328 [1852]), pertaining to an illegal purchase of State stocks by a bank. Characterizing his judicial temperament and writing style on the occasion of Judge Gardiner’s death, Rochester attorney William Cogswell observed,

[t]here have been judges of greater learning, but in large comprehensiveness and true judicial wisdom, it is doubted whether he is surpassed by any. . . . The intellectual and moral qualities which characterized him as a judge, and by which he attained to his excellence, were directness, comprehensiveness, vigor, and intense love of the right. His opinions are simple, terse, business-like documents. . . . He never wrote a line to display his learning or for rhetorical effect. He had a remarkable capacity of seizing the controlling facts of a case; an almost intuitive perception of its real merits. The hesitating utterance of the truth by the timid was not lost upon his receptive ear, the subtle perversion of it by the disingenuous did not deceive or mislead him. He was fearless, deciding the right as he believed it, un-influenced by popular feeling or opinion (Memorial Address, at 23).

Although Judge Gardiner left public life in 1855, his years in so-called retirement were many and full. “So great was the confidence of the bar and the public in his diligence, integrity and learning that he was constantly selected as a referee to whom the most important cases were referred for his decision” (Proctor, 45 Alb L Journal at 11). In this manner, he served for approximately twenty years. Judge Gardiner also enjoyed life on his farm in Gates, just outside the Rochester city limits, and “pitched his hay and tended his farm long past the age when most men attend to anything” (Memorial, Monroe County Bar [June 7, 1883], In Memorium, Addison Gardiner, at 9).

Perhaps most notable in discussing Judge Gardiner’s life are the glowing tributes that recognized not only his legal achievements but also his character as a citizen and man. Contemporaries heaped effusive praise and admiration on Judge Gardiner as a “pleasant, genial, kindly man. His temper was always cheerful. His wit was always ready. He had a kindly word for old lawyers and for young lawyers. . . . Everybody liked Judge Gardiner, and those who knew him well had a strong personal affection for the sagacious, well-balanced, upright, kindly, pleasant man” (id.). Though overtures were made to attract Judge Gardiner back into politics, Judge Gardiner steadfastly and good-naturedly refused to reconsider his removal to private life. He died on his farm on June 5, 1883, having “preserved both his mental and physical vigor up to his final illness” (Peck, Semi-Centennial History of the City of Rochester, 653-666 [1884]). On June 9, 1883, the Court of Appeals adjourned “out of respect to the memory of Addison Gardiner,” and Chief Judge Ruger offered remarks noting Judge Gardiner’s “calm, judicial temper, combined with great integrity, learning, and strong common-sense” (Court of Appeals Tribute [June 9, 1883], In Memorium, Addison Gardiner, at 6). The Ulster County Town of Gardiner, New York, formed in 1853, was named for Judge Gardiner, apparently in recognition of his service as Lieutenant Governor.

Progeny

Judge Gardiner married Miss Mary Selkrigg in 1831. They had two children, Charles A. and Celeste M. In 1884, son Charles, age 42, died tragically on the eve of his wedding day, leaving no children. While making final preparations to travel to his fiancee’s home in Elmira, he was stricken with apoplexy and died within hours of first reporting to his sister that he was not feeling well. Daughter Celeste married George W. Loomis and had one daughter. Celeste Gardiner Loomis died in 1832 at age 82. Celeste’s daughter, Celeste Loomis, married Nelson P. Sanford, a prominent Rochester attorney who later became a judge. Celeste Loomis Sanford died in 1975 at age 86. She had no children; thus, her death ends the line of direct descendants. The Gardiner family burial plot is located in Mount Hope Cemetery in Rochester.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

History of the Bench and Bar of New York, David McAdam et al eds., New York History Co. (1897).

In Memorium, Addison Gardiner , Privately Published (containing tributes of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York and of the Bar of Monroe County, New York and the addresses of William F. Cogswell on behalf of the Bar of Monroe County, and the Rev. Charles E. Robinson).

“Judge Addison Gardiner: He Refuses to be Named for Any Office in the Democratic Convention,” New York Times, July 17, 1876.

Landmarks of Monroe County, provided by Monroe County Historian’s Office (on file with the editor).

“Mrs. Loomis of Pioneer Family Dies,” Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, February 21, 1932.

Obituary, Celeste Sanford, Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, February 28, 1975.

Obituary, New York Times, June 6, 1883; Tribute, June 9, 1883.

Our Towns History, http://www.gardiner.ny.us/TownHistory/townhistory.htm.

Peck, Semi-Centennial History of the City of Rochester, 653-666 [1884], available at http://www.rootsweb.com/~nymonroe/bios/biographies019.htm.

Proctor, Addison Gardiner, 45 Alb L Journal 7, 10 (1892).

“Rites Tuesday at Home for Mrs. Loomis,” Rochester Times-Union, February 22, 1932.

“Suddenly Summoned,” Rochester Union & Advertiser, April 30, 1884.

There Shall Be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York (booklet on file with the Court).

Published Writings

We are unaware of any articles or books authored by Judge Gardiner.

Endnotes

- “a short prayer comprising an invocation, petition, and conclusion” (Webster’s New Collegiate Dictionary 218 [1981]).

- Associate Judge, Court of Appeals, 1854, 1856-1862; Chief Judge, 1862.

- Associate Judge, Court of Appeals, 1862-1865.

- See also, History of the Bench and Bar of New York (David McAdam et al eds., New York History Co. [1897]), at 333 (“Judge Gardiner gave a perfectly fair and impartial hearing to both the state and the prisoner”).

- New York Times, June 26, 1852.