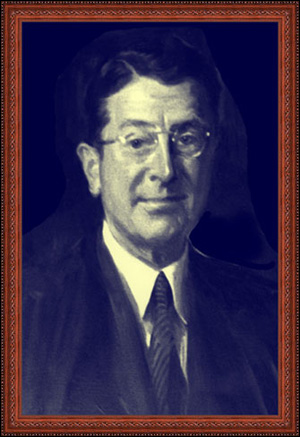

Judge Van Voorhis wrote well over a thousand formal legal opinions, including his dissents, and participated in thousands of cases which came before him during his thirty-one years on the bench.

He was born July 14, 1897, in the farm house now occupied by his daughter Allis and her husband on Thomas Avenue in the Town of Irondequoit. In fact, Dr. Thomas, after whom the road was named, delivered him. The judge’s father, Eugene Van Voorhis, was a distinguished lawyer and president of the Monroe County Bar Association. He was a member of the firm of John Van Voorhis & Sons, which also included at the time of the judge’s birth, his grandfather, John Van Voorhis, Jr., and his uncle, Charles Van Voorhis. In 1896, Eugene Van Voorhis married Allis Sherman, who was a dynamic lady in her own right, having a spirit more like her father’s first cousin, William Tecumseh Sherman, than her own mild-mannered father.

The law firm which the judge’s grandfather had started prospered from the hard work of its partners. John Van Voorhis, Jr. left the farm he grew up on in the Mendon-Bloomfield area to come to Rochester to read law in 1848 in the office of John W. Stebbins. At the time, his father – the Judge’s great-grandfather, also John Van Voorhis – who was a farmer during the week and a Methodist minister on Sundays, believed his son was headed for eternal damnation. By his reckoning, not only was farming the only virtuous occupation, but the practice of law was immoral.

Nonetheless, the judge’s grandfather had a spectacular career. Although he never went beyond eighth grade in school, he taught himself Latin and French. After reading law he opened his own office in 1851 in Rochester (later joined by his brother Quincy) and acquired a number of well-known clients, including Frederick Douglas, the Seneca Nation of Indians and others in whose causes he believed. He was elected to Congress three times (1879-1894) and was so outspoken in defense of his causes that he narrowly escaped being reprimanded by the House for speaking too often and too vehemently the first year he was there. As a lawyer, after winning several large awards in negligence cases against the Buffalo, Rochester and Pittsburgh Railway, he received from the railway an offer to be its general counsel. In his response he politely declined, stating that he could make more money suing than representing them. In 1872, as a result of his service to the Republican party, the judge’s grandfather was named counsel to the Monroe County Election Commissioners. In 1872 the commissioners consulted him as to whether they could register a young woman by the name of Susan B. Anthony. His reply was that they could. In his opinion the word “man” in the constitution was generic for both men and women, since the latter also enjoyed constitutional rights. As a result she voted on November 5, 1872. The rest, of course, is history, but when her trial came on the judge’s grandfather not only represented the three commissioners, but was co-counsel with Judge Henry R. Selden for Susan B. Anthony herself.

Judge Van Voorhis was born into an active family deeply involved in the political and legal issues of the day. Since his father had moved from the City of Rochester to the Town of Irondequoit in 1896, the judge grew up in a very rural setting. Irondequoit at that time had only a few hundred people, virtually all farmers, and was several hours by steam railway or horse and buggy from the city. In fact during his early years he and his parents would move into his grandfather’s house in the city during the winter months. This multi-generational set-up was not the easiest on the future Judge’s mother, but educational and stimulating for him.

During his early years on the farm the judge’s closest associates were the animals around him. His dog “Rowdy,” his pony “Raggie-lug” (which he rode to first place in the Irondequoit Pony Show as a young boy), and a turkey gobbler with a gender identification problem which sat for nearly six weeks on a collection of apples in the ground hoping they would hatch.

As a young boy he had his own ideas about the beauty of indigenous flora, and one day, when his parents were away, he dug a bunch of pretty little three leaf plants in the woods and planted them around the house. Unfortunately he learned the hard way about poison ivy. At his fifth birthday party, which included romping around naked in the mud pond across the road, the guest list consisted of five young lads his same age. As a sign of the judge’s loyalty to his friends and theirs to him, all but one of them attended his 80th birthday, 75 years later.

In grade school he attended local private schools in the Rochester area. For high school he went to the Hill School in Pottstown, Pennsylvania, from which he graduated with honors and a prize in public speaking. From the Hill he matriculated at Yale College in 1915. In both boarding school and college he had a heavy dose of the Latin and Greek classics, although his major in college was history. He was admitted to the Phi Beta Kappa society his junior year and graduated in 1919 with Philosophical Orations (Yale’s version of a degree summa cum laude). During a hiatus for six months when, because of World War I, Yale closed down, he returned to Rochester and worked as a cub reporter for the Democrat & Chronicle.

After graduating from Yale, he sought out advice from the heads of the leading law schools of the day. First he went to Columbia Law School and spoke personally with Dean Harlan F. Stone (later a justice of the U.S. Supreme Court) who, after reviewing his academic record, wanted to enroll him at Columbia. He then went to Yale Law School and was interviewed by Dean Thomas W. Swan (later a judge of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit). Dean Swan likewise wanted to sign him up at Yale Law School. But he wanted to consult additional advisers, so he went to the Harvard Law School, where he was interviewed by their relatively new Dean, Roscoe Pound. After listening to his account of his family and their interest in the law, Dean Pound recommended that he return to Rochester and read law under his father and uncle. This was consistent with his own account of his father’s advice that he should “learn the law through the soles of my shoes” rather than in the academic world. As Judge Van Voorhis explained, “The real reason, as father said, was that he thought I was theoretically-minded enough as it was, and that if I didn’t get down to brass tacks pretty soon, I would never know what it was all about.”1

In 1919 he filed his clerkship papers, passing his bar exams in 1922. In fact, he did so well on his bar exams that a copy of them was retained by the state law examiners and placed in the official archives of the state library to show what a young man could do by reading law instead of going to law school. Despite never having earned a law degree, he ultimately was awarded honorary LL.D. degrees from Hobart College, Albany Law School, University of Rochester, Brooklyn Law School, and New York Law School (where he was an adjunct professor after retiring from the bench).

After being admitted to the bar in 1922, he practiced with his father and uncle until he was elected in 1936 as a Justice of the state Supreme Court. During this interval he took whatever cases he could get his hands on, trying virtually all of the Town Justice Court cases available in the office. By 1924 he was in need of his own secretary and interviewed a number of prospects, giving each one a paragraph or two of dictation. One applicant took down the dictation in shorthand, went to a typewriter (manual in those days), and then quickly typed the dictated paragraphs perfectly, including correct spelling and punctuation. He hired her on the spot. Her name was Evelyn Renagle, later known by her married name, Evelyn Fleming. She remained his secretary throughout his career until she died in the spring of 1983, fifty-nine years later.

On June 2, 1928, Judge Van Voorhis married Linda Gale Lyon (called by her parents and friends “June”). His wife, despite being a very kind, generous, and cultured lady, was very determined, and when she set her sights on him, he did not have a chance. Throughout the judge’s public career she was a great help to him politically, often smoothing sensitive political situations. The judge and his wife had three children, Emily (Mrs. Edward R. Harris), June Allis (Mrs. Louis D’Amanda) and Eugene. At the time of his death he had thirteen grandchildren and several great-grandchildren.

In the late 1920s, Van Voorhis became interested in the reform wing of the Town Republican Party led by Tom Broderick, then the Town leader. In 1928, Broderick wrested control from the previous town administration and became Supervisor. Broderick got the town board to name John Van Voorhis as town attorney, a post he held until he went on the bench (but for one year when the Democrats took control of the board).

As town attorney, Van Voorhis took a leading role in one of the leading political controversies of the day: public works financing. Historically, during the 1920s and earlier, there were no particular statewide or even town standards for the acceptance of highways, or even subdivision improvements. Developers would get suburban towns to sell municipal bonds to finance the infrastructure for their developments, claiming that the towns would get their money back through higher assessed values after the houses in these tracts were built. When the depression came, the tracts in many towns including Irondequoit were largely devoid of houses, but the interest on the bonds had to be paid.2 Many towns actually went through insolvency, and the national bankruptcy act was amended to give municipalities and political subdivisions bankruptcy protections. One of the first serious attempts to govern the acceptance of roads from developers came with the enactment of former Section 278 of the Town Law (now Section 279) by chapter 634 of the Laws of 1932. The enactment of this law and others like it was strongly endorsed by Supervisor Broderick and by his town attorney, John Van Voorhis.

But from these endeavors, the pair made political enemies. The Town convinced New York State to sue, on the Town’s behalf, several prominent contractors and engineers to recover money obtained illegally from various public districts, boards and officers of the Town.3 In that case the defendants settled for $600,000.00 in 1929. Van Voorhis represented the Town in other litigation involving some of the most prestigious law firms of the day and won.4 By doing so, the seed of opposition to his political advancement had been sown. When Broderick, who by 1936 had become County Republican Leader as well as Supervisor of Irondequoit, proposed Van Voorhis for nomination to the State Supreme Court, Mr. Nixon of the Hubbell, Taylor, Goodwin, Nixon & Hargrave firm and number of other prominent corporate attorneys sought to have the Monroe County Bar Association declare him unfit. The judge’s uncle Charles, who kept his ear to the ground politically, learned of what was going on and when Mr. Nixon and others organized a meeting of the association to vote on Van Voorhis’s qualifications, his uncle Charles and his father got a number of their old friends, some of whom happened to be judges, to come to the meeting early and sign up as speakers. Since speakers were taken in order of signing, four or five of the sitting judges spoke first, all in strong praise of Van Voorhis’s legal abilities. In the face of such praise, his prominent opponents were never able to get the Bar Association to pass their motion declaring him unfit. As a footnote to the judge’s entry into politics, Broderick first offered him the nomination to Congress, which he declined on the grounds that it would require political compromises which he could not make in good conscience.

From 1937 through part of 1947, Judge Van Voorhis sat as a trial justice on the State Supreme Court, Seventh Judicial District, and in 1944 he was nominated by the Republican State Committee for election to a vacancy on the Court of Appeals. The nomination was moved at the state convention by the venerable Judge William E. Werner, former judge of the Court of Appeals. But although he carried upstate by nearly a million votes, he was trounced in New York City. Brooklyn alone brought in a million-vote plurality for his opponent, Judge Marvin Dye, with whom Judge Van Voorhis later became very good friends.

In 1947 Governor Dewey designated Van Voorhis to the Appellate Division, First Department at the request of Presiding Justice Francis Martin, who was acquainted with his opinions as a trial judge and very much respected his work. For the next six years he sat in New York for two weeks out of every month. To keep in touch with the bench and bar in Rochester, however, he continued to hold Special Term in the Seventh Judicial District when not in New York. Unlike many judges at Special Term he had a reputation for deciding most motions straight from the bench, dictating into the record his opinions, complete with case names and citations.

In 1953, Governor Dewey appointed Judge Van Voorhis to fill a vacancy on the Court of Appeals. Sometime later at a cocktail party in New York City, Dewey remarked to him that only a strong Governor could have appointed him to the bench because of his independence of mind and decisions, which, though scrupulously following the law, were sometimes politically unpopular. An illustration of what the Governor meant surfaced the next year, when Judge Van Voorhis had to run for election to the Court of Appeals. He handily received the Republican nomination, but the Governor wanted him to be cross-endorsed by the Democrats.

A number of his former colleagues on the Appellate Division, First Department, who had been prominent in the New York City Democratic Party organization, encouraged his cross-endorsement. Upon hearing what was going on, both David Dubinsky, president of the International Ladies Garment Workers Union, and Alex Rose, president of the United Hat, Cap and Garment Workers, activists in and leaders of the Liberal Party, cut short their vacations and flew back to New York to lobby against his cross-endorsement. At that point Dewey rapidly returned from his vacation out west to lobby in favor of his appointee. After some intense inter-party discussions, Judge Van Voorhis was nominated at the Democratic Party state convention by the leader of the Bronx and seconded by the leader of Monroe County, who together managed to prevail on a majority of the delegates. Judge Van Voorhis ran on both the Republican and Democratic lines in the general election.

As an appellate court judge, he was a prolific writer of opinions. While he is perhaps best remembered for some of his dissents (almost 200 in all), he wrote many more opinions for the majority on both the Appellate Division (126) and Court of Appeals (204).

Virtually all of the legal issues which are regarded as “hot” today were treated in his decisions. He was immensely concerned about protection of what Maitland and other writers about English law would call the rights and liberties of the subject as against the increasing powers of the state. Judge Van Voorhis believed that the right to private property is among the most important of these basic rights. For example, how good is the right to free speech, he reasoned, if the government can take away property from a speaker it dislikes? The same question can be asked of freedom of assembly or freedom of political action or many other basic constitutional rights. He regarded private property rights as a valuable counterbalance to the enormous power and control of government.

The twentieth century saw numerous examples of ruthless regimes that successfully appropriated private property without compensation as a means of political control. In his dissenting opinion in St. Nicholas Cathedral of the Russian Orthodox Church v. Kedroff (276 A.D. 309, 321 [First Department, 1950] [Van Voorhis, J, dissenting]), Judge Van Voorhis pointed out that Stalinist control of the property of St. Nicholas Cathedral in New York City would in effect prevent free exercise of religion as guaranteed by the first and fourteenth amendments to the federal constitution.5

He firmly believed the “rule of law” to have been derived from the idea that certain rights such as those to life, liberty, and property are fundamental to the American idea of a free society.6 Blackstone’s observation expressed a legal concept fundamental to Judge Van Voorhis’s thinking and jurisprudence when he wrote over two hundred years ago:

“So long as these [rights to life, liberty and property] remain inviolate, the subject is perfectly free; for every species of compulsive tyranny and oppression must act in opposition to one or other of these rights, having no other object upon which it can possibly be employed.”7

The gradual evisceration of the “public use” limitation on the power of eminent domain was a matter he wrote on often, starting with his dissent in Kaskel v. Impelliteri (306 N.Y. 73 [1953], cert. den. 347 U.S. 934, 98 L.Ed. 2085). In that case he questioned the necessity of taking the entire 6.3 acres between Columbus Circle and Ninth Avenue in Manhattan for the removal of the slum conditions along Ninth Avenue, especially when the property included the Manufacturer’s Trust Building, the Manhattan offices of the General Motors Corporation, and the bus terminal of the Baltimore and Ohio Railroad. In his dissent he said “slum clearance” was being used merely as an excuse to take land for the proposed New York Coliseum.

Similarly he dissented in Cannata v. City of New York (11 N.Y. 2d 210 [1962]) in which was questioned the constitutionality of the statute pursuant to which the City proposed to condemn 95 acres of land in Brooklyn for resale to unidentified private developers for the “Flatlands Urban Industrial Park.” He opposed what he considered to be an extension of the slum clearance rationale of Kaskel to permit eminent domain to be used to acquire properties that were not substandard (but might become such), so that they might be resold to “private developers whose projects are believed by the municipal administration to be more in harmony with the times.”

He dissented again in Courtesy Sandwich Shop, Inc. v. Port of New York Authority (12 N.Y. 2d 379 [1963]), disputing that the statute authorizing condemnation of lands in lower Manhattan for the World Trade Center was constitutionally deficient.8 In Courtesy, he believed that by permitting the Port Authority to condemn all sorts of perfectly good rental properties in order to construct new rental properties to be rented by the Port Authority to other private tenants, the last remaining excuses for a “public use,” even the fairly slim ones in the Cannata case, were cast aside and that the “public use” constitutional limitation in the fifth and fourteenth amendments to the federal constitution and the corresponding state constitutional provisions were effectively nullified.

Some forty years later the concerns which he expressed in those dissents have been prominently echoed in the recent dissents of Justice Sandra Day O’Connor and Justice Clarence Thomas in Kelo v. City of New London (545 U.S. 469, 125 S. Ct. 2655 [2005]). Although the property owners lost in Kelo on a five to four vote, Judge Van Voorhis would have been both surprised and pleased to see such diverse groups as The National Association of Home Builders, sixteen or more distinguished law professors, the King Ranch, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People, AARP, the West Harlem Business Group, and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference, among others, filing briefs amicae in support of the positions he put forward in his dissents in Kaskel and its progeny.

He also had a distrust of the growing power of administrative bodies and the exercise of quasi-legislative and executive power in essentially the unelected, undemocratic organs of government, but recognized that in our modern complex society the place of administrative law and the functions of bureaucracies were indispensable.9

In line with his comments in his Cornell Law Quarterly article, Broad Fields of Law, Judge Van Voorhis voted in a number of cases to uphold the administrative decisions of local boards or administrative bodies.10 In one of his earlier decisions, he held in Vangellow v. City of Rochester (190 Misc. 128 [1947]) that the city’s adoption of a major street plan which involved designating a ten-foot strip across plaintiff’s property for future highway expansion did not wholly void the city’s ordinance and that the court could do no more than refer the matter to the Zoning Board of Appeal.

At the same time, he freely opposed administrative bodies when he thought they had acted improperly, unconstitutionally, or outside of their jurisdiction.11 In cases where there was a background of political pressures behind administrative action, Judge Van Voorhis was especially careful to see that unreasonable or arbitrary administrative action be stopped. In Trio Distributor Corporation v. City of Albany (2 N.Y. 2d 690 [1957]), the Good Humor Corporation challenged a local law that required a second attendant to be on its trucks to protect and safeguard children gathered around to buy anything appealing to children, whatever that might be. The record showed a series of legislative attempts (at least one of which had previously been declared unconstitutional) by the City of Albany to circumscribe the activities of ice cream peddlers (Schrager v. City of Albany, 197 Misc. 903 [S. Ct., Rensselaer Cty, 1950]). Implicit in the record were facts indicating that a political leader of Albany wanted to protect a local rival business from competition by Good Humor. In an opinion by Judge Van Voorhis, the Court held that the wording of the statute was unconstitutionally vague.

In Sleepy Hollow Valley Committee v. McMorran (20 N.Y. 2d 190 [1967]), the issue before the court was whether the State Superintendent of Public Works had the power to change 3.5 miles of the route for a state highway specifically designated in Chapter 290 of the Laws of 1965. Although no specific reason was given for the deviation, the route originally designated by the legislature was to have passed through certain prominent estates in Pocantico Hills. Writing for the court, Judge Van Voorhis held that the power of the Superintendent to modify highways so designated by the legislature was limited by law to minor ones for engineering reasons, and that there were factual issues involved requiring the denial of the motion to dismiss the complaint.

He was especially concerned by inroads on citizens’ property rights through zoning, and in numerous opinions or dissenting opinions discussed limits on such powers.12 Perhaps his most compelling dissent on the subject of zoning he wrote in People v. Stover (12 N.Y. 2d 462 [1963]), which involved the enactment of a zoning ordinance banning clotheslines in front and side yards, ostensibly to eliminate one family from protesting the tax rates in the City of Rye by drying their clothes in their front yard. Judge Van Voorhis wrote:

My concern in this case is not with limitation of free speech nor whether aesthetic considerations are enough in themselves to justify zoning regulations in prescribed instances, but with the extent to which a municipality can go in restricting the use of private property.

He summed up his opposition to such zoning:

This ordinance is unrelated to the public safety, health, morals or welfare except insofar as it compels conformity to what the neighbors like to look at. Zoning, as important as it is within limits, is too rapidly becoming a legalized device to prevent property owners from doing whatever their neighbors dislike. Protection of minority rights is as essential to democracy as majority vote. In our age of conformity it is still not possible for all to be exactly alike, nor is it the instinct of our law to compel uniformity wherever diversity may offend the sensibilities of those who cast the largest votes in municipal elections. The right to be different has its place in this country. The United States has drawn strength from differences among its people in taste, experience, temperament, ideas, and ambitions, as well as from differences in race, national or religious background. …This is not merely a matter of legislative policy, at whatever level. In my view, this pertains to individual rights protected by the Constitution.

Judge Van Voorhis wrote on many other issues. He was a great believer in privacy rights, which he discussed at some length in an article he wrote for the New York Law School in 1967 reviewing Professor Alan F. Westin’s book Privacy and Freedom (Athenaeum Press, New York, 1967). He believed such rights stemmed from various provisions in the United States Constitution. In his dissent in Sackler v. Sackler (15 N.Y. 2d 40, 45-46 [1964]), he urged the court to reverse a judgment in a matrimonial case on the grounds that the evidence of the wife’s adultery was improperly admitted since it had been obtained by an illegal forcible entry into the wife’s home by the husband and a couple of private investigators employed by him.

On the other hand he also recognized that such rights to privacy had to be tempered somewhat in order to protect society against lawlessness and other clandestine anti-social acts.13 The greatest threat of governmental intrusion into our personal lives he felt occurred through tax laws, securities regulation, environmental regulations, administration of Social Security, Medicare, and other programs which those who are the most vocal in espousing the so-called “right to privacy” tend to fervently support.14

In line with his views on privacy, he tended to oppose state interference with personal or family relations. In Seiferth v. Mosher (309 N.Y. 80 [1955]), he wrote the court’s opinion refusing a petition of the Deputy Commissioner of Health of Erie County to have a young lad with a cleft palate declared a neglected child and removed to the custody of the Commissioner so that he could be forced to have a corrective plastic surgical operation. He ends his opinion with characteristic modesty, saying, “One cannot be certain of being right under these circumstances, but this appears to be a situation where the discretion of the trier of the facts should be preferred to that of the Appellate Division” (at p. 85-86).

In Parker v. Hoefer (1 N.Y. 2d 873 [1956]), where the court upheld a Vermont judgment against defendant for alienation of affections and criminal conversation under Vermont Law for acts allegedly committed in New York, Judge Van Voorhis dissented on the grounds that such a judgment was against the public policy of the State of New York, which had abolished such causes of action and therefore the Vermont ruling was not subject to the full faith and credit clause of the federal constitution.

In criminal matters his opinions were balanced. On the one hand, he was opposed to technical legal requirements which could doom a prosecution when the evidence of guilt was clear beyond a reasonable doubt.15 On the other hand, he believed the police and prosecutors should play by the rules, such as the constitutional restrictions on searches and seizures.16 He also insisted that proof beyond a reasonable doubt be shown prior to conviction, as he set out in his dissent in People v. Halio (13 N.Y. 2d 1073 [1963]) in which a doctor was convicted of the crime of abortion. In several cases, he voted to reverse convictions in which the defendant had not been given an adequate opportunity to defend.17 He believed that when courts have sentenced repeat offenders for longer periods of time based on prior convictions, such prior convictions must be sustained and properly verified as to the type of crime involved.18

Finally, he felt strongly that crimes which were defined based on events, such as death occurring during the commission of what was essentially a malum prohibitum misdemeanor, should only be counted as felonies if the underlying misdemeanor was intended by the perpetrator and not simply a breach of the law without any criminal intent, as he discussed in his dissent in People v. Nelson (309 N.Y. 231), regarding a manslaughter conviction. Whenever possible he felt that criminal sanctions should be imposed on the basis of knowingly intending to commit a crime, as he argued in his dissent in People v. Gray (1 N.Y. 2d 728, 729-731 [1956]).

There were a number of other areas of continuing importance that his decisions touched upon. Although he was quite skeptical, especially in his later years, about organized religion,19 he voted with the majority in Engel v. Vitale (10 N.Y. 2d 174 [1961]), upholding the constitutionality of the Regent’s Prayer in public schools, a decision reversed by the Supreme Court in Engel v. Vitale (370 U. S. 421 [1962]). Judge Van Voorhis felt that, as long as all sectarian references had been removed, a prayer which asked God’s blessing on students’ parents, teachers, and fellow students was not a bad thing for students to pray. But in Board of Education v. Allen (20 N.Y. 2d 109 [1967], affirmed 392 U.S. 236, 20 L.Ed. 2d 1060 [1968]), Judge Van Voorhis dissented vigorously from the majority opinion upholding the constitutionality of Chapter 320 of the Laws of 1965 as amended by Chapter 795 of the Laws of 1966 providing for purchase of text books with public moneys for parochial school students on the grounds that it violated the establishment clause of the First Amendment to the U.S. Constitution and the analogous provision in the New York Constitution. His concern was centered on the practical inability to distinguish between secular and religious views expressed in text books and the inevitable pressure for the state to dominate the churches through the provision of text books which would be politically correct as well as concern over the influence of religion on the state. He ends his dissent with support for the positions taken by Madison and Jefferson in favor of clear separation of church and state. His dissenting position was adopted by Justices Black, Douglas, and Fortas in their dissenting opinions in the United States Supreme Court. Mr. Justice Douglas specifically referenced Judge Van Voorhis’s reasoning as a basis for his own.20

Although his father was an agnostic, Judge Van Voorhis was deeply moved by the Cranmerian liturgy of the Episcopal Church while in his college years, and helped organize All Saints Episcopal Church in Irondequoit after he was married, where he served as a vestry person for many years. Despite his later skepticism of organized religion, especially what he regarded as its espousal of moralistic causes, many from a “left-wing” or socialistic perspective, he continued to attend church regularly until his death.21

As could be seen from his position in the censorship cases in which he wrote dissenting opinions or joined in the dissents of other members of the court, as well as his writings on religious topics, Judge Van Voorhis was not much for moralistic self-righteousness.22 In a matter reviewing the sentencing of a former football coach from Westchester, who had been prosecuted for sodomy, albeit apparently consensual, with a 17-year-old member of the team, Judge Van Voorhis did not join in the moralistic outrage expressed by the other judges in affirming the man’s sentence of a lengthy prison term at Sing Sing. Rather, he expressed the opinion that the man should be removed from contact with school students and put on intensive probation with supervision by the Corrections Department, but that sending the man to Sing Sing would be, in effect, a death sentence. True to his supposition, the defendant in that case was found dead in his cell only a short time after his incarceration.

Some of his dissents have now been vindicated by the Supreme Court of the United States. His dissent in Jenad, Inc. v. Scarsdale (18 N.Y. 2d 78 [1966]) arguing that an administrative body’s predicating a land use permit on the permanent cessation to the public of private property interests in land must bear a proper connection to the effects or purposes of the approval sought in order to be constitutionally valid was adopted years later by the United States Supreme Court in Dolan v. City of Tigard (512 US 374, 129 L Ed2d 304 [1994]) in which Chief Justice Rehnquist writing for the court took the position enunciated in Judge Van Voorhis’s dissent (129 L.Ed. 2d 304, 319).

Judge Van Voorhis’s dissents in People v. Peters (18 N.Y. 2d 238 [1966]) and People v. Sibron (18 N.Y. 2d 603 [1966]), arguing that there was insufficient probable cause for the search of the defendants, were adopted by the Supreme Court in Sibron v. State and Peters v. State (392 U.S. 40, 20 L.Ed. 2d 917 [1968]). The Supreme Court as a whole, although there were numerous concurring opinions, also vindicated his dissenting opinion in Matter of Kingsley International Pictures Corporation v. Regents of the University of the State of New York (4 N.Y. 2d 349 [1958]).23

Despite his interest in the law, Judge Van Voorhis had many other interests, including sailing, which he did from the age of four (when he sailed with his father and uncle) through his years as skipper of both International Rule Eight and Twelve Metre yachts (when he won many coveted trophies on Lake Ontario) until about a year before he died (when he still sailed competitively with his son and grandsons). He also loved classical music and learned to play the flute well enough to play in the Rochester Symphony Orchestra, a distant predecessor of the present Rochester Philharmonic Orchestra.

He had a wonderful sense of humor, about almost everything other than socialism. He used to regale his family with all kinds of stories at dinner, including some from his favorite comic strip as a boy, “Mutt & Jeff”; many of which had a discernable moral to tell. Perhaps because of his closeness with nature in his rural upbringing, he would reduce things quickly to their essentials. It is reported that at one time Chief Judge Conway assembled the members of the Court to announce to them that the Budget Bureau and the Governor were going to support an appropriation to renovate the Court of Appeals. When he solicited the views of Judge Van Voorhis after telling him of the millions that were to be spent, the judge’s retort was that he would be perfectly happy if they would fix the radiator valve in his office so he could turn the heat down.

As a parent, he was always very supportive of his three children, even if his schedule meant that he would come home later than most fathers. Many times during the winter he would take all three of them cross-country skiing in the pitch dark after supper, when they would walk over the hills at Eaton Road or in Durand Eastman Park near where he lived in Irondequoit. In the other months of the year, he would go horseback riding with them and of course, during the summer months, sailing. If the wind changed at night and/or the temperature dropped sharply, it would be his large frame in his night shirt that would appear at their bedroom door to make sure the children were properly covered. And when they were small, he would often sing to them as they went to bed in his comforting baritone “Now the day is over, Night is drawing nigh, Shadows of the evening, Steal across the Sky.”

As a young man he bought an Indian motorcycle, which he enjoyed riding before he was married. During the 1930’s he was active as a volunteer firefighter with the St. Paul Fire District in Irondequoit. He was also one of the original directors of the first “Blue Shield” plan in Monroe County and a Trustee of Highland Hospital. During World War II, in order to save gasoline, he went back to riding a motorcycle, this time a Harley Davidson. His wife and children often rode with him, sometimes two at a time (one in front and one in back).

After retiring from the Court of Appeals, he continued to practice law for the next sixteen years in loose association with his son Eugene under the firm name of Van Voorhis & Van Voorhis. During that time he argued a number of significant cases including Hurd v. City of Buffalo (34 N.Y. 2d 628 [1974]) and Waldert v. City of Rochester (44 N.Y. 2d 831 [1978], appeal dismissed 439 U.S. 922, 58 L.Ed. 2d 315 [1978]), which resulted in decisions holding the real property taxes of the Cities of Buffalo and Rochester in excess of their constitutional limit. He was appointed in 1968 by the United States District Court, District of Connecticut as special master to determine the right, title, and interest of the New Haven Railroad in the Grand Central Terminal Properties in the bankruptcy reorganization of that railroad. He was also appointed and served as one of three distinguished arbitrators in the arbitration proceedings to determine whether the federal government through the Overseas Private Investment Corporation was obligated to pay the investment insurance claim of the International Telephone and Telegraph Corporation upon the nationalization of its telephone operations in Chile by the Allende government.

On November 25, 1983, Judge Van Voorhis died of complications arising out of a chronic septicemia, or as one of his doctors put it, maybe from just old age. He is interred in Rochester’s Riverside Cemetery in a family plot which includes his parents and wife.

Progeny

Judge Van Voorhis’ daughter Emily in 1963 married Edward Ridgway Harris, a native of Rochester, New York, who for many years worked as a mathematician and computer scientist for IBM in Rochester, Minnesota. They have four children: Cornelia Kurschner of Grand Marais, Minnesota, who is a teacher and artist with three children; Edward Talcott Harris of Atlanta, Georgia, an actor and producer without children; the Rev. Jonathan Harris of Roanoke, Virginia, an Episcopalian priest without children; and Stephen Harris of Belleview, Washington, a computer scientist with two children.

His daughter June Allis married Louis D’Amanda in 1954. D’Amanda, also a native of Rochester, New York, graduated from Cornell Law School and later worked for and became a partner in the Rochester, New York law firm of Chamberlain, D’Amanda, where he concentrated on negligence litigation. They have four children: Dorothy Hayes of Irondequoit, New York, who has ten children and four grandchildren; John Francis D’Amanda of Pultneyville, New York, who has three children and is now a partner in Chamberlain, D’Amanda, Gale Fox of Irondequoit, New York, and is a former member of the United States Equestrian Team, with three children; and Christopher D’Amanda of Pittsford, New York, a teacher and ceramic artist, who has three children.

In 1961, his son Eugene married Heide Bussebaum, a native of Frankfurt, Germany. They had five children: John Van Voorhis of Washington, D.C., a computer scientist who has two children; Charles Van Voorhis, a partner in the architectural firm of Durland and Van Voorhis of New Bedford, Massachusetts, who has four children; Norman Van Voorhis of Pittsford, New York, a teacher with four children; Louise Gleason, of South Miami, Florida, a licensed physical therapist with two children; and Linda Lyon Bowen, of Webster, New York, a teacher with three children. Eugene’s wife died in 1996. Eugene is currently of counsel to the law firm of Harris, Chesworth, O’Brien, Johnstone, Welch and Leone, LLP. in Rochester, New York.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Certain unpublished articles and papers of John Van Voorhis, including:

Address to New York Law School Alumni Luncheon, February 4, 1966.

Paper entitled “Wicked Secular World” presented to the Fortnightly club in 1981.

Miscellaneous records and files of the law firms of John Van Voorhis & Sons and Van Voorhis & Van Voorhis.

Reading Law in a Common Law Office, John Van Voorhis, a paper he wrote c.1967.

Review of Professor Alan F. Westin’s book Privacy and Freedom, Athenaeum Press, New York, 1967.

Personal interviews with the late Hon. John Van Voorhis, his mother, the late Allis S. Van Voorhis and numerous other family members and friends.

Published Writings Include:

The Place of Law in Life Especially the Laws of Private Property, 5 Whittier L. Rev. 483 (1983).

Frivolous Attacks Can Undermine Judiciary, Rochester Democrat & Chronicle, May 31, 1977.

Expert Opinion Evidence, 13 N.Y.L.F. 651 (1967).

Tribute to Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, 52 Cornell L. Rev. 351 (1966-1967).

Note on the History in New York State of the Powers of Grand Juries, 26 Alb. L. Rev. 1 (1962).

Cardozo and the Judicial Process Today, 71 Yale L. J. 202 (1961-1962).

Some General Observations Concerning Insurance Law, 27 Ins. Counsel J. 271 (1960).

Broad Fields of the Law, 44 Cornell L. Q. 469 (1958-1959).

Endnotes

- See minutes of the Court of Appeals on the Death of Hon. John Van Voorhis, entered December 12, 1938.

- The facts recited in such cases as Town of Irondequoit v. Johnson (231 A.D. 264 [Fourth Department, 1931]) and in Sage v. Broderick (255 N.Y. 19 [1930]) and the records on appeal in those cases illustrate the difficulties the Town of Irondequoit had in paying for bonded debt used to finance infrastructure improvements for private developers.

- This litigation by the state is unreported in the official reports, but is described in 158 Misc. 123 at page 143.

- In Town of Irondequoit v. County of Monroe (158 Misc. 123 [Supreme Court, Monroe County, 1935]), Van Voorhis, acting as of counsel to the Town, took on a number of very prominent Rochester law firms. The referee’s report in the Town’s favor was confirmed by the Fourth Department, 254 A.D. 933 (1938), appeal dismissed, 279 N.Y. 658 (1938).

- The position taken by Justice Van Voorhis in his dissent in the Appellate Division, First Department was adopted by the Court of Appeals in an opinion by Conway, J. at 302 N.Y. 1 (1950) reversing the Appellate Division, which decision of the Court of Appeals was then reversed by the United States Supreme Court in an opinion written by Mr. Justice Reed, Kedroff v. St. Nicholas Cathedral (344 U.S. 94 [1952]) and remanded to the Court of Appeals. On remand in an opinion by Conway, J., the Court of Appeals held that while the statutory ground upon which its prior decision was based had been declared unconstitutional the common-law cause of action still remained and even under Watson v. Jones (13 Wall. 679), the court had the duty to inquire as to the legitimacy of the hierarchical church body claiming the right of church governance, 306 N.Y. 38 (1953), Van Voorhis, J. taking no part in this decision, and ordered a retrial of the question of who had the right of possession on the common-law issue. After the retrial the Court of Appeals directed entry of judgment against the representatives of the Moscow Patriarch (7 N.Y. 2d 191 [1959]). Judge Van Voorhis concurred in this decision. This decision was then reversed by the Supreme Court of the United States in a Per Curiam opinion (363 U.S. 190, 4 L.Ed. 2d 1140 [1960]). Whereupon the Court of Appeals amended its remittitur to conform with the Supreme Court’s decision affirming the lower court judgments to evict the archbishop elected in the United States and turn the property over to the representatives of the Moscow Patriarch (8 N.Y. 2d 1124 [1960]).

- See The Place of Law in Life Especially the Laws of Private Property, Hon. John Van Voorhis, Whittier Law Review, Vol. 5, 1983, No. 4.

- Blackstone’s Commentaries on the Laws of England, Vol. I, Legal Classic Library Edition, 1993, p. 140.

- 12 N.Y. 2d 379, 398. Judge Van Voorhis wrote: “If powers such as these be upheld to condemn property in good condition which is not potentially slum (cf. Cannata v. City of New York, 11 N.Y. 2d 210) without even paying for the good will, what may appear to be for the advantage of the New York City Chamber of Commerce or the Downtown Lower Manhattan Association . . . today may be turned against them tomorrow, as their counterparts learned in other countries to their sorrow and dismay after they surrendered to the collectivist state. This ever-growing ascendancy of government over private property and over free enterprise is no respecter of persons and cannot long be harnessed by those who expect to use it for private ends. * * * * Disregard of the constitutional protection of private property and stigmatization of the small or not so small entrepreneur as standing in the way of progress has everywhere characterized the advance of collectivism.”

- See Broad Fields of the Law, John Van Voorhis, 44 Cornell L. Q. 469 (1958-1959).

- In RKO-Keith-Orpheum Theatres, Inc. v. City of New York (308 N.Y. 493 [1955]), he wrote the court’s opinion upholding the action of the New York City Council in applying its 5% tax on theater tickets to add one whole cent wherever the correct amount calls for half or a major fraction of a cent. In Atlantic Beach Property Owners’ Association, Inc. v. Town of Hempstead (3 N.Y. 2d 434 [1957]), he wrote the opinion of the court upholding the right of the Town Board to extend a park to include new developments despite a private agreement to use the same solely for the Association’s members, holding that the Town could not have accepted land for park purposes on condition that it renounce powers and duties which the legislature has conferred upon it in the creation, enlargement or administration of town parks. In Chiropractic Association of New York, Inc. v. Hilleboe (12 N.Y. 2d 109 [1962]), he wrote the court’s opinion upholding the power of the Public Health Council to adopt regulations restricting persons authorized to take or direct the taking of X-rays. In Matter of Hub Wine & Liquor Co., Inc. v. State Liquor Authority (16 N.Y. 2d [1965]), he concurred with the opinion of the court written by Bergan, J. upholding the power of the State Liquor Authority to approve the transfer of a retail liquor store license to a new location, despite prior rule requiring a certain distance between stores, which court characterized as anti-competitive. In Swan Lake Water Corp. v. Suffolk County Water Authority (20 N.Y. 2d 81 [1967]), the court in an opinion by Van Voorhis, J. held that the issue of which of two water providers should service the Brookhaven Memorial Association, Inc. hospital was a matter within the jurisdiction and expertise of and should be determined by the Water Resources Commission.

- See dissent of Van Voorhis, J. from the court’s upholding an award by the Workmen’s Compensation Board in Penzara v. Maffia Brothers (307 N.Y. 15 [1954]), where a mechanic, fixing his own automobile with his employer’s equipment, was injured. He also dissented in Spielvogel v. Commissioner of the Department of Water Supply, Gas and Electricity if the City of New York (1 N.Y. 2d 558 [1956]), where appellant’s master electrician’s license was revoked because he also worked part-time as a motion picture operator, and in Paterson v. University of the State of New York (14 N.Y. 2d 432 [1964]), where the court upheld the constitutionality of Article 148 of the Education Law providing for licensing of “Landscape Architects.” Judge Van Voorhis in his dissent wrote as follows:

“The statutory definition of what constitutes practicing as a landscape architect (Education Law, Section 7320, subds. 2, 3) and the exclusions exempted by section 7326 are so indefinite as to render it impossible for a person to know in advance whether he is violating this law by practicing without a license. It is too vague for a criminal statute. Moreover, much of the broad field attempted to be covered has no relation to the public health, safety, morals or welfare and hence is beyond the reach of the police power (at p. 440).

“In Swalbach v. State Liquor Authority (7 N.Y. 2d 518 [1960]), he concurred with the court’s opinion by Fuld, J., holding that denial of an application of a licensee to move into a “shopping center” on the basis of such a policy was unreasonable. Similarly in Williamson v. New York State Liquor Authority (14 N.Y. 2d 360 [1964]), Judge Van Voorhis, writing for the court, held that if permission for a licensee to move was denied on the grounds that there was insufficient showing that the public would be properly served in the area now located after the move, where evidence showed that there were four liquor stores in the current area and only three in the area to which licensee wanted to move, the matter should be sent back to the SLA for further consideration of the effect of the move on both areas. Judge Van Voorhis joined in the court’s opinion by Foster, J. in Association for the Preservation of Freedom of Choice, Inc. v. Shapiro (9 N.Y. 2d 376 [1961]), which held that the refusal of a justice of Supreme Court to approve the certificate of incorporation of the Association and the refusal of the Secretary of State to file the same because of political objections to the purposes of the organization were unconstitutional.” - In Matter of Long Island Lighting Company v. Horn (17 N.Y. 2d 652 [1966]), Judge Van Voorhis dissented from the court’s upholding the right of the Zoning Board of Appeals of the Town of Huntington to require the utility to put 3.1 miles of high voltage transmission lines underground after the Public Service Commission had approved the lines to be overhead through vacant properties. He reasoned that on the subject of utility regulation, the PSC had more expertise than the ZBA and that its views should be deferred to. In Presnell v. Leslie (3 N.Y. 2d 384 [1957]), he dissented from the court’s ruling upholding the Board of Appeals of the Village of Westbury in prohibiting amateur radio operators’ towers above a residential zone of more than 20 feet. In Matter of Sierra Construction Co., Inc. v. Board of Appeals of the Town of Greece (12 N.Y. 2d 79 [1962]), he dissented from the majority opinion upholding the Board of Appeals on the grounds that the zoning ordinance which established a set-back line based on what future builders might build on the street in question improperly delegated a legislative function to the subsequent private builders. In Vernon Park Realty, Inc. v. City of Mount Vernon (307 N.Y. 493 [1954]), he concurred with the majority opinion which held the zoning affecting a former parking lot of the New York, New Haven & Hartford Railroad to be so destructive of the value of the property involved as to be unconstitutional.

- Review of Professor Alan F. Westin’s book Privacy and Freedom, Athenaeum Press, New York, 1967.

- In his review of Professor’s Westin’s book, Judge Van Voorhis comments: ” The balance of privacy in the United States is continuously threatened by egalitarian tendencies demanding greater disclosure and surveillance than a libertarian society should permit.”

- In his op-ed piece published in the Democrat & Chronicle on May 31, 1977, Judge Van Voorhis wrote:

“I recall a case in the New York Court of Appeals years ago, while I sat there, in which the accused shot and killed a jeweler in Buffalo while committing a robbery. While questioning him, the police asked what he did with the gun? He replied that he threw it over the Peace Bridge into the Niagara River while returning home to Hamilton, Ontario. Through brilliant police work, the revolver was dredged from the bottom of the Niagara River by the use of powerful magnets. It was delivered to ballistic experts who proved scientifically that it had shot the bullet that had been extracted from the body of the victim. His conviction of first degree murder was quickly affirmed and he went to the electric chair. But that was before the decision by the Supreme Court in Miranda. If it had been afterward the defendant would still probably be walking the streets.” - See the dissents of Van Voorhis, J. in People v. Peters, 18 N.Y.2d 238 (1966) and People v. Sibron (18 N.Y.2d 603 [1966]).

- See People v. Freudenberg (5 N.Y.2d 209 [1958]) where Judge Van Voorhis joined in the dissent of Desmond , J. on the grounds that the defendant had not been adequately appraised of his rights to have a lawyer.

- See dissenting opinion of Van Voorhis, J. in People v. Von Glahn (308 N.Y. 662 [1954]).

- See Wicked Secular World, John Van Voorhis, 1981, a paper he presented to the Fortnightly, a scholarly group in Rochester, New York. In this paper he discusses his own religious journey as follows:

“In my freshman year at college I became confirmed as a high church Episcopalian. The reverence and beauty and basic simplicity of the services and the medieval hymns, translated mostly by Reverend John Mason Neale, and the certainty of faith which they reflected greatly appealed to me. I devoured the New Testament and especially the gospels which I accepted, not word for word, but as revelation from on high as validly interpreted by the church. I also believed that Jesus Christ was unique in the world, and that by his life and death he was the saviour and redeemer of the world. I continued as a regular churchgoer for the major part of the rest of my life.

“At the same time, however, my mind was not idle both in the fields of science and ethics. I could never fully bring myself to a belief imposed by authority, even of the most exalted kind, without testing it by reason. Neither could I believe that the wise and the good people are left out who ante-dated Jesus or who have not belonged to a church.

“In the summers I worked in the law office of my father and uncle. They were not only good lawyers, but men of the highest ethical standards and convictions. But the whole system of law and government at the same time seemed at many points inconsistent with what I read in the New Testament. As a lawyer and judge I have never been able to reconcile the law of this or any other country with the beatitudes or the sermon on the mount, although the latter may on occasion have reduced the litigiousness and pettiness of litigants. Following a life long policy, I do not readily throw over ideas or practices that are valuable simply for the reason that they appear inconsistent, and believe that there is some underlying reconciliation which I may later come to understand. But there is a limit to what one can accept on this basis. The theologians seem to have realized this in characterizing much that is in the New Testament as counsels of perfection. That means, if I interpret it aright, that these monitions are not written off entirely, but are not expected to be followed literally by the church or any person in conducting the affairs of this world.

“These conclusions of mine, barely sketched here, have lead to a good deal of skepticism on my part about much that is written in the Bible or practiced or preached in churches.” - Mr. Justice Douglas in his dissent specifically referred to the dissenting opinion of Van Voorhis, J. as follows: “Judge Van Voorhis, joined by Chief Judge Fuld and Judge Breitel, dissenting below, said that the difficulty with the text book loan program ‘is that there is no reliable standard by which secular and religious textbooks can be distinguished from each other'” (392 U.S. 236, at pp. 257, 258).

- Van Voorhis’s views on how some clerics view capitalistic businesses are illustrated by the following quotation from his essay, “Wicked Secular World”:

“As everybody knows, George Eastman was a great philanthropist. His gifts to charity and education were most carefully and wisely planned to serve the greatest good which he could conceive for the greatest number. But Eastman’s greatest service to humanity consisted not in his benefactions, but in the founding and development of the Eastman Kodak Company – making possible on a large scale the joy and many uses of photography and the creation of hundreds of thousands of jobs throughout the world. Yet I once heard a bishop of the Episcopal Church preach about how evil the Eastman Kodak Company and the Xerox Company are, and how wicked this country was to fail to prevent the starvation which Nigeria was then inflicting on Biafra in one of their internecine wars. The congregation were told that they should experience some of the starvation of the Biafrans for spiritual reasons in order to know how wicked we really were and to expiate our sins. It did not seem to occur to the good bishop that a few companies like Kodak and Xerox in Africa would have helped to alleviate starvation, or that if his precepts were adhered to there would be more starvation in the United States.

“It seems to me that clergymen and philosophers put too little emphasis on the enduring value of our temporal pleasures and accomplishments and steady, if not spectacular, attention to doing our parts of the work of the world. Jesus was, after all, a carpenter for longer than he was an evangelist. Of course, the work of the world is often humdrum, just as it must have seemed humdrum to Mr. Eastman when in the early history of the company he slept in a hammock in his factory and was awakened every hour of the night by an alarm clock to stir the emulsions. He would not have done this under socialism. There is a moral value in doing the day’s (or night’s) work faithfully and anonymously even though the product is material, temporal and animated mainly by selfish motives. Being secular is no warrant for laziness or incompetence about material things. Our interdependence emphasizes this. I never take off on a commercial airliner without being thankful for the innate morality of the maintenance people who have serviced the plane. No active person in modern life could live out the day were it not that a similar sense of morality animates millions of people working for gain in the performance of their unheralded secular responsibilities. Performing these secular duties faithfully belongs to the essence of loving one’s neighbor. To a religious minded person it is loving God too, and doing His will. It is more so, to my mind, than becoming befuddled by many of the esoteric supernaturalisms which have confused so many pulpits.” - Judge Van Voorhis dissented in Matter of Kingsley International Pictures Corporation v. Regents of the University of the State of New York (4 N.Y. 2d 349 [1958]), where the Court upheld the banning of the film “Lady Chatterley’s Lover,” and in People v. Fitch (13 N.Y. 2d 119 [1963]), involving a criminal prosecution for selling “Tropic of Cancer,” and in Larkin v. G. P. Putnam’s Sons (14 N.Y. 2d 399 [1964]), upholding an injunction sought by the New York City Corporation to prevent the sale/distribution of the eighteenth century book “Fanny Hill.”

- See Kingsley International Pictures Corporation v. Regents of the University of the State of New York, (360 U.S. 684, 3 L.Ed. 2d 1512 [1959]).