On September 9, 1971, more than 1,000 inmates rioted at Attica State Correctional Facility in Western New York. A guard and three inmates were killed during the siege. Four days later, heavily armed state troopers, sheriff’s deputies, and prison guards stormed the prison to free the hostages. In the resulting battle, 10 prison employees and 29 inmates died and more than 80 people were wounded. During the aftermath, charges surfaced that crimes committed by law enforcement officers during the siege were covered up by the State.

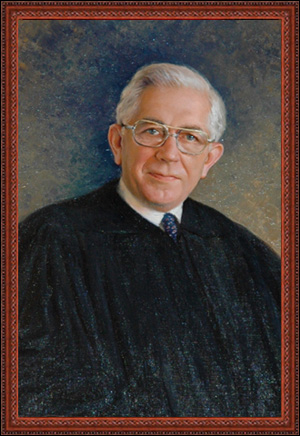

Judge Bernard S. Meyer was called upon by Governor Hugh Carey to investigate the Attica uprising. After an exhaustive eight-month inquiry, Judge Meyer released the first volume of his findings, a 570-page document that came to be known as “the Meyer Report,” which carefully reviewed all the facts and found that the State had made “serious errors in judgment” in handling the Attica affair, but concluded that there had been no “intentional coverup” by the prosecution. Very few people could command the respect of all parties in this political time bomb. As anyone who ever met him would agree, Judge Meyer was such a person-a careful and decisive man who utilized the rule of law to become a compassionate champion for people from all walks of life.

Born in Baltimore, Maryland, on June 7, 1916, as one of three siblings, Bernard S. Meyer earned an undergraduate degree from John Hopkins University in 1936 and graduated first in his class only two years later from the University of Maryland School of Law. His lifelong propensity to challenge, rather than accept, flaws in the law became evident in his law school notes when be began to make margin notes to “Change this in the legislature.” Even at a young age, he had established himself as a judicial activist, in the finest sense of the word.

Judge Meyer was admitted to the Maryland bar in 1938 and worked early in his career in the office of general counsel for the United States Treasury Department. He interrupted his practice of law to serve in the U.S. Navy in the Pacific during World War II. In 1947, he moved with his wife, the former Elaine Strauss, and their daughters, Susan and Patricia, to New York State. He was admitted to the New York bar that same year. From 1947 through 1958, he was a partner at Meyer, Fink, Weinberger and Juliano in New York City. While he never ran for the legislature, Judge Meyer was active in politics, as evidenced by his service as Nassau County Democratic Chairman from 1957-58. He established a deep friendship with Jack English, who succeeded him as Democratic Chairman, and with whom he later partnered in the firm of Meyer, English and Cianciulli from 1975 to 1979. After his years on the Court of Appeals, he would return to this firm, now Meyer, Suozzi, English & Klein, for the remainder of his legal career.

In November of 1958, Meyer was elected to Supreme Court, Tenth Judicial District, a position he would hold for 14 years. Only eight months after his election, Judge Meyer presided over a landmark school prayer case that made its way to the United States Supreme Court, Engel v. Vitale (370 US 421 [1962]). In a 46-page opinion, he upheld the use of the nondenominational prayer recommended by the State Board of Regents, ruling it constitutional as long as students were not required to say the prayer. Although his holding was overturned by the United States Supreme Court in a controversial decision prohibiting school prayer, the Engel case, like the Attica Report, illustrates, as eloquently phrased by Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye at his September 19, 2005 memorial tribute, how Bernard S. Meyer honored the stability of the law, followed precedent where it led, and became a judicial role model.

Judge Meyer’s propensity for hard work was evident to anyone who knew him. His daughter Patricia recalls his insatiable love of reading and working, even on family vacations. A notorious seven-day-a-week workaholic, Judge Meyer truly enjoyed his passion as much as anyone would embrace activities such as golf, the theater, or travel. Indeed, he described his passion as “my overweening infatuation with that jealous mistress, the law.”

His “mistress” did not, however, prevent him from addressing head-on the problems of society in a larger context, rather than simply issuing decisions affecting only the named parties. The law allowed him to express himself as a “reformer at heart.” His definition of a judicial activist (which he did not abjure) was

. . . a Judge who tries to see not just the legal problem presented by the papers or in the trial immediately before him or her but the whole problem faced by the parties involved, the problem in relation to the whole body of the law, the problem in relation to law as a part of the whole fabric of society.1

He considered judicial activism a way of seeking improvement in the delivery of justice in a holistic manner.

During his judicial career at the trial level, he found the energy to serve as the Chair of the National Conference of State Trial Judges, President of the Association of Judges of the New York State Supreme Court, member of the Board of Directors of a National Center for State Courts, Chair of the New York State Bar Association’s Judicial Selection Committee, and founder of the Council of Judicial Associations and the New York Fair Trial Free Press Conference. In his spare time, he also served on the Board of the National College of State Trial Judges, now the National Judicial College, in Reno, Nevada.

His myriad accomplishments while serving on the judiciary include authoring the 1962 amendments to the Domestic Relations Law, which made sweeping changes to better the law in this sensitive area. From 1962-1979, he served as chair of the Pattern Jury Instruction (Civil) Committee of the Association of Justices of the Supreme Court, which published a two-volume compendium of instructions. These instructions are virtually the Bible for trial attorneys and judges, and help to standardize jury charges in a myriad of areas. Judge Meyer’s daughter, Patricia, recalls her mother Elaine and her father poring over galley proofs of the PJI in the 1960s at the dining room table during her father’s “free” time.

Judge Meyer’s scholarly analysis and writings while on the Supreme Court bench did not go unnoticed. As confirmed by former Chief Judge Sol Wachtler, who served concurrently with Judge Meyer as a Justice in Nassau County, Judge Meyer received national prominence as one of the leading judges in the country on zoning issues as a result of his meticulously reasoned and clearly written opinions. No matter the topic, his clear thinking, logic, and persuasive analysis made the law come alive to help the lives of everyday people.

In the early 1970s, Judge Meyer unsuccessfully sought election to the New York State Court of Appeals on three separate occasions. Though disappointed, he did not give up, and in 1979, was appointed to the Court by Governor Hugh Carey, serving for seven distinguished years before mandatory retirement. During his tenure on the State’s highest Court, he continued his frenetic work pace and, along with the Court, continued to be a compassionate champion for the people who most needed help from the law. He participated in decisions interpreting the New York State’s Constitution to provide individual rights broader than those contained in the Federal Constitution.2

The hallmark of Judge Meyer’s writing style, which even he jokingly referenced in his retirement remarks, was his propensity to produce a “Judge Meyer-type sentence.” As described by Chief Judge Kaye, it was “one comprehensive sentence packed to the brim and then some, and very, very, very long.” As he explained to his law clerks at the Court of Appeals, he wanted to start off each opinion with a sentence that would concisely and clearly inform the reader of the issue involved and why it was being resolved in a certain way to ensure that the law would be lucid and predictable to the legal community, which, in turn, would benefit not only the bench and bar but the common person who was required to know the law in its practical application. Many people who did not share the brilliance of Judge Meyer may have been intimidated by his long and developed sentences, which often required a couple of rereadings. More to the point, this methodology demonstrated his intense and undying desire to articulate each narrow problem faced by the parties in a case in the larger context of the entire body of law and as part of the fabric of society. Each decision was intended to fit carefully within the clear universe of the law rather than be an emotional departure to fit someone’s preconceived notion of fairness. As Chief Judge Kaye opined, Judge Meyer followed “precedent where it led” thus serving as a true “judicial role model.”

An activist until the end of his brilliant career as a Judge on the Court of Appeals, Judge Meyer extended his activism to criticizing the constitutional and statutory requirements that forced him to resign from the Court of Appeals at age 70. In his retirement remarks, he spoke eloquently for a revision of the mandatory retirement provisions that prohibited him from continuing his work at the Court of Appeals, but would nevertheless allow him to return to the trial bench until age 76. Consistent with his body of work, he questioned the age restriction as bearing “little relation to logic.” Not unexpectedly, given his prolific history of acting to correct perceived flaws in legislation, he published a book entitled Judicial Retirement Laws of the 50 States and District of Columbia, wherein he comprehensively surveyed existing judicial retirement laws, suggesting how these laws should be improved.

The word retirement could never apply to Judge Meyer. He returned to private practice with the vim and vigor of a new associate, once again joining the now-Mineola firm of Meyer, Suozzi, English & Klein. He concentrated on appellate and trial litigation, arbitration, and mediation in connection with municipal agencies and real estate. As he had before becoming a Judge, he was renowned for working dawn to dusk at the firm until his death on September 7, 2005. For the last several years of his life he coauthored a massive work of scholarship, with Burton C. Agata and Seth H. Agata, entitled The History of the New York Court of Appeals 1932-2003. Published by Columbia University Press in 2006, this ambitious book tracks the Court’s jurisprudence for the time period and picks up where Judge Francis Bergan‘s The History of the New York Court of Appeals 1847-1932 leaves off.

Bernard S. Meyer was a giant of a man and a judge’s judge. He also enjoyed life with a zeal which was matched only by his brilliance and compassion. One of his favorite sayings was that he had been blessed with “an embarrassment of riches.” He deeply appreciated the blessings bestowed upon him and endeavored to share those blessings with all those connected with the law-from his fellow judges right down to the janitor of the courthouse. Based on his outstanding contributions to the body of law in such diverse areas as Workers’ Compensation, family law, civil practice, fair trial/free press, school prayer, and judicial retirement itself, it is clear that while Judge Meyer may have had “an embarrassment of riches,” he lavished those riches generously upon a grateful public.

Progeny

Judge Meyer’s older daughter, Susan, died tragically in 1961. Twelve years later, his marriage to Elaine Strauss ended in divorce. In 1975, he married Edith B. Gilbert, who passed away in 1989. His survivors include his third wife, Hortense Fox Handel; daughters Patricia, of Charlottesville, Virginia, and Gail LaPlante of Seaforth, Ontario; son Lee Handel of Cleveland; and five grandchildren.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

In Memoriam, 5 NY3d xi (2005).

New York Times obituary, September 8, 2005.

Published Writings Include:

Some Problems the Court of Appeals May Be Faced with under the Death Penalty Statute, 48 Syracuse L. Rev. 1499 (1998).

Is There Cause for Jubilee? 50 Md. L. Rev. 227 (1991).

Some Thoughts on Statutory Interpretation with Special Emphasis on Jurisdiction, 15 Hofstra L. Rev. 167 (1987).

Justice, Bureaucracy, Structure, and Simplification, 42 Md. L. Rev. 659 (1983).

The New York Proposed Code of Evidence: Some Background and Some Suggestions, 47 Brook. L. Rev. 1237 (1981) (with Richard T. Farrell).

Should Notice Be a Prerequisite to Use of Prima Facie Evidence? 19 N.Y. L.F. 785 (1974).

Commentary, 12 Duquesne L. Rev. 470 (1974).

Questions Juries Ask: Untapped Springs of Insight, 55 Judicature 105 (1971) (with Maurice Rosenberg).

The Expert Witness: Some Proposals for Change, 45 St. John’s L. Rev. 105 (1970).

The Trial Judge’s Guide to News Reporting and Fair Trial, 60 J. Crim. L. Criminology & Police Sci. 287 (1969).

News Reporting and Fair Trial, 22 Okla. L. Rev. 135 (1969).

Some Problems Concerning Expert Witnesses, 42 St. John’s L. Rev. 317 (1968).

Free Press v. Fair Trial: The Judge’s View, 41 N.D. L. Rev. 14 (1964).

Recognition of Exchange Controls after the International Monetary Fund Agreement, 62 Yale L.J. 867 (1953).

Legislative History and Maryland Statutory Construction, 6 Md. L. Rev. 311 (1942).

Tort Liability under the Wartime Car Sharing Plan, 11 Geo. Wash. L. Rev. 1 (1942).

Endnotes

- 68 NY2d xi.

- E.g., People ex rel Arcara v. Cloud Books, 68 NY2d 553 (1986); People v. P.J. Video, Inc., 68 NY2d 296 (1986), People v. Johnson, 66 NY2d 398 (1985); People v. Bigelow, 66 NY2d 417 (1985).