Introduction

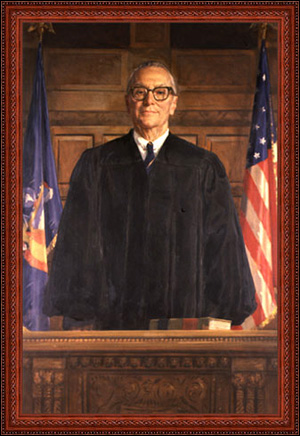

Charles Stewart Desmond served on the Court of Appeals for 26 full years-the second longest tenure of a Judge on the Court of Appeals. He was, at the time of his appointment, the second youngest man to ever be elected to the Court and was the first Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals to also hold the title of Chief Judge of the State of New York.1 He was a devout family man and the pride of Buffalo, New York. The prestigious Moot Court competition at the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Law bears his name to this day.

Judge Desmond was born in a room above his father’s saloon near the Lake Erie docks in Buffalo on December 2, 1896; he was the son of Patrick Desmond and Katherine Jordan Desmond. His grandfather was a very strong-willed railroad man from County Court, Ireland.2 Judge Desmond attended Immaculate Conception grade school where he was selected to give the commencement speech in 1910. He graduated in 1913 from the Jesuit-run Canisius High School, where he developed a lifelong connection to Catholic principles and a flair for Latin.

Charles Desmond obtained an A.B. degree in 1917 and an M.A. degree in 1918 from another Jesuit institution, Canisius College. At Canisius, Desmond received many academic honors, participated in several dramatic productions, was an editor and frequent contributor to the Canisius Monthly (a literary magazine), served as an officer for the Athletic Association in football and basketball, and was elected senior class president.3

The First World War briefly interrupted Desmond’s studies. He served as gunnery sergeant and a second lieutenant in the United States Marines Flying Force. However, he caught influenza during training and did not serve overseas before the Armistice. Upon his graduation from Canisius, he entered law school at the University of Buffalo where he received his LL.B. degree in 1920. Desmond was admitted to the New York Bar on October 16, 1920.4

Desmond engaged in the general private practice of law in Buffalo from 1920 to 1939, first as an associate of, and then as a partner with, Thomas C. Burke. Not much is known of Desmond’s private practice, but he did practice considerable admiralty law.5 During this period he became active in Democratic Party politics. In 1928, at the age of 33, he married Helen Ryan in Buffalo. The couple had four children: Ryan, born 1929; Sheila, born 1931; Kathleen, born 1932; and Patricia, born 1938.

In the early 1930’s Desmond was mentioned as a possible United States Attorney for the Western District of New York, but President Roosevelt chose another for the post. In 1935, during the middle of the Great Depression, Governor Herbert Lehman appointed Desmond to the New York State Board of Social Welfare, an entity which had supervision over private asylums and charity institutions in the state. During this time, Desmond became increasingly involved in various welfare and civic organizations in western New York.6

Desmond experienced an almost meteoric rise to the Court of Appeals. In January 1940, Governor Lehman appointed Desmond to the vacancy on the State Supreme Court created when Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division, Fourth Department, Charles Sears was appointed to the Court of Appeals. Desmond would need to run for office that November to secure the full 14-year term. His political sponsor, Paul E. Fitzpatrick, tried to persuade western New York Republicans to cross-endorse Desmond for the full elective term on the Supreme Court in the fall of 1940. When Fitzpatrick failed to secure the cross endorsement, he decided instead to put Desmond’s name on the ballot as the Democratic candidate for the Court of Appeals. Desmond secured the nomination and then defeated his opponent in the general election.

Judge Desmond was so well admired and well respected that when he ran for reelection in 1954, he was cross-endorsed by all major political parties. He was elected as Chief Judge in November 1959 and took that seat on January 1, 1960, following the retirement of Chief Judge Albert Conway. Judge Desmond served as the 28th Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals until he reached the constitutional age limit of 70 and his term expired on December 31, 1966. During his more than a quarter of a century on the Court, he wrote more than 700 opinions and by his own estimation participated in over 12,000 appeals.

Writing Accomplishments

In 1949, Judge Desmond published his first book, called Sharp Quillets of the Law (From Decisions of the New York Court of Appeals),7 a collection of 83 unusual and curious cases decided by the Court between 1847 and 1947. Designed for the lay person, the work gives a glimpse into the kinds of cases that reached the Court during its first 100 years and offers a brief view into the workings of the Court.

In 1959, Judge Desmond followed up Sharp Quillets with Through the Courtroom Window, which he designed in a similar format to his first book by collecting 32 short descriptions of cases that reached the Court during his tenure. Among the highlights of the book are Judge Desmond’s account of People v. Valletutti (297 NY 226 [1948]), a felony murder case where the Judge authored the majority opinion reversing the conviction; People v. Conroy (287 NY 201 [1941]), a capital murder prosecution where-following the Court of Appeals’ affirmance of the conviction -the defendant was executed; and People v. Wolfe (304 NY 556 [1952]), a fantastic murder prosecution where the defendant insisted on trying to represent himself and claimed he was God.

The gem of the book may be the vignette, entitled “The Crime that was Never Committed.”8 In very readable prose, Judge Desmond recounts the full story of People v. Trowbridge (305 NY 471 [1953]), which, many New York lawyers will remember from their law school days, is famous for the rule of evidence prohibiting bolstering. Desmond’s account of Trowbridge, and the robbery that never occurred, yields three remarkable insights. First, the case demonstrates how a seemingly technical rule of evidence, often criticized by the public as responsible for letting the guilty go free, can produce equitable results. Second, Trowbridge shows that juries are made up of human beings who do not always come to the right answer in a criminal case. Third, and perhaps most significantly, the case is revealing of the rules that assigned counsel worked under prior to Gideon v. Wainwright (372 US 335 [1963]). Judge Desmond observes that a key aspect of the case was the able representation by “a youthful but able and aggressive lawyer (John A. Murray of Troy)” who represented Trowbridge without compensation.9 At that time, only lawyers appointed by the court in capital cases were entitled to compensation for their services; lawyers appointed by the court to serve indigent defendants in noncapital cases worked for free in “the fine old traditional rule of the profession.”10

Apart from his two books, Judge Desmond was a prolific contributor to legal journals, covering almost every major subject. Judge Desmond’s writings frequently ventured beyond the realm of state law. For example in 1943, he spoke to the graduates of Canisius College warning against American isolationism:

Our acceptance, after victory is ours, of our share of world responsibilities added to the sacrifices in the conflict itself, will give us the right to be heard as to the interpretation of the war aims we have announced…We shall then have the right to say that ‘freedom for all peoples’ was no mere slogan…Let us face the fact that colonial empires are things of the past, and then perhaps wars, too, will become things of the past.11

Judge Desmond’s writings were frequently influenced by Catholic moral teachings on natural law and social justice. On the bench, natural law principles no doubt influenced his opinions for the Court in Packer Collegiate Inst. v. University of the State of New York (298 NY 184 [1948])-holding an Education Law statute, requiring registration of private nonsectarian schools under the Board of Regents, unconstitutional as an invalid delegation of legislative power-and People ex rel. Portnoy v. Strasser (303 NY 539 [1952])-overturning a lower court order that removed a child from her mother’s custody and firmly establishing that the custodial parent has sole control of the child’s upbringing.

In a 1943 speech, Judge Desmond observed: “Disabuse your minds of any idea that Catholic teaching as to moral law conflicts with American traditions, history or law system.”12 Judge Desmond rejected the criticisms directed at believers in natural law: “We need not be ashamed of being naive when we find ourselves in the company of Cicero and Sophocles, Blackstone and Chief Justice Marshall, as well as the greats minds of our own Church.”13 Judge Desmond continued: “Either we admit that there is a higher law, not of our making to which the majority is subject and the majority is bound, or we have the way wide open to totalitarianism.”14

In an address at a symposium held by the Guild of Catholic Lawyers of New York City in December 1953, Judge Desmond asserted: “from the Republic’s founding days till now, the decisions of our highest courts have repeated over and over that there is a higher or natural law, antedating all positive law and expressing fundamental rights which governments and constitutions do not grant and cannot take away, but must protect, and that the courts must strike down as unconstitutional legislative or administrative acts of government repugnant to natural justice.”15

Prayer from his faith tradition also permeated his public speeches. Thus, on the retirement of Chief Judge Albert Conway in December 1959, Judge Desmond stated:

and we pray for you (Chief Judge Conway) in the words of Cardinal Newman: ‘may He support us all day long till the shades lengthen and the evening comes, and the busy world is hushed and the fever of life is over and our work is done. Then in His mercy may He give us a safe lodging and a holy rest and peace at the last.’16

Work as a Court of Appeals Judge

Judge Desmond served 19 years as an associate judge under four Chief Judges. During this time, he refined a very forceful and lean writing style. As noted by former Presiding Justice of the Fourth Department Michael Dillon, Judge Desmond “was a master in the use of words, insisting always upon precision of language-and particularly so in the art of opinion writing. . . . He wrote exactly what he meant to say, sprinkled with just enough Latin to provide emphasis and reflect his liberal arts Jesuit training.”17

Judge Desmond was difficult to classify politically. According to the New York Times, he was generally regarded as a leader of the liberal wing of the Court, but his opinions often defied easy characterization.18 Judge Desmond’s progressive side was illustrated most notably in criminal law and criminal procedure law, illustrated, for example, by his dissents in People v. Prior (294 NY 405 [1945]) and People v. Spano (4 NY2d 256 [1958], revd sub nom Spano v. New York, 360 US 315 [1959]) and by his majority opinion in People v. DiBiasi (7 NY2d 544 [1960]).19

In the area of First Amendment law, Judge Desmond could be regarded as a balancer. He was no absolutist and somewhat conservative, at least from a current perspective. In People v. Doubleday & Co. (297 NY 687 [1947], affd by an equally divided Court 335 US 848 [1948]), he joined a unanimous Court in upholding a conviction of a publisher for releasing a book “composed of six interrelated stories” that were allegedly “obscene and lewd.” In Joseph Burstyn, Inc. v. Wilson (303 NY 242 [1951], revd 343 US 495 [1952]), Judge Desmond joined a majority of five Judges and concurred separately in upholding a determination of the Board of Regents which revoked a license to exhibit a motion picture on the ground that it was “sacrilegious.” The Judge’s concurring opinion specifically upheld the right of the government to censor motion pictures, and advocated a deferential standard of judicial review of the state regulators’ decision that the film was sacrilegious, a term he concluded was constitutionally no less vague and definite as the term “obscene.”

The Judge, however, was not a sure vote in favor of censorship. He wrote the opinion for the Court in Matter of Excelsior Pictures Corp. v. Regents of Univ. of the State of N.Y. (3 NY2d 237 [1957]) striking down a Board of Regents’ refusal to grant a license to a motion picture called “Garden of Eden” on the ground that it was “indecent.” The Judge held that the word “indecent” within the meaning of Education Law ‘ 122 means “obscene” and that the picture, which was a fictionalized description of a nudist group in a secluded private camp in Florida, was not obscene nor was it found to be obscene by the Board of Regents. Nevertheless, the very next year in Matter of Kingsley Intl. Pictures Corp. v. Regents of the Univ. of the State of N.Y. (4 NY2d 349 [1958]), he concurred with the majority in holding constitutional the Board of Regents’ decision to deny a license to the film “Lady Chatterley’s Lover” that had been based on the ground that the film was immoral because it “‘portray[ed] acts of sexual immorality…or lewdness’ and… ‘present[ed] such acts as desirable, acceptable or proper patterns of behavior.'”20

Judge Desmond’s position on the relationship between the First Amendment and obscene or pornographic works can best be illustrated in his extrajudicial writings. The Judge noted in his characteristically direct style:

My thesis, so far as I have one, is that there is nothing in American law, constitutional, statutory or conventional, to prevent pre-censorship for obscenity, and that pre-censorship, applied reasonably and justly and without destruction of real literary values is not offensive to historic American tradition of freedom of publication.

. . .

We agree with Thomas Jefferson that as to the general content of newspapers, interference is the worst of all evils, since ‘our liberty depends upon the freedom of the press, and that cannot be limited without being lost.’ But obscenity, real serious, not imagined or puritanically exaggerated, is today as in the past centuries, a public evil, a public nuisance, a public pollution.21

In the area of tort law, Judge Desmond could be viewed as a moderate. On the pro-defendant side, he dissented from the majority in Battalla v. State of New York (10 NY2d 237 [1961]), which gave a plaintiff a cause of action where she alleged that the defendant’s employee had failed to lock her securely into a ski-lift and, even though there was no physical impact, she suffered emotional damages. He also dissented in Klimas v. Trans Caribbean Airways (10 NY2d 209 [1961]), a case where the majority upheld an award of workers’ compensation benefits to an employee whose fatal heart seizure was allegedly brought on by workplace stress and anxiety. Finally, in Badigian v. Badigian (9 NY2d 472 [1961], overruled in part Gelbman v. Gelbman, 23 NY2d 434 [1969]), the Judge refused to abandon the rule that immunized a parent from negligence actions brought by the parent’s son or daughter.

As illustrated by other many tort cases, however, the Judge could be considered pro-plaintiff. The leading example is the Judge’s opinion in Woods v. Lancet (303 NY 349 [1951]), holding that an individual could recover damages for injuries she alleged the defendant negligently inflicted while she was still in her mother’s womb. In a classic common-law passage, Judge Desmond wrote:

[Lack of precedent] . . . is not a very strong reason . . . in a case like this. Of course, rules of law on which men rely in their business dealings should not be changed in the middle of the game, but what has that to do with bringing justice to a tort-feasor who surely has no moral or other right to rely on a decision of the New York Court of Appeals? Negligence law is common law and the common law has been molded and changed and brought up-to-date in many another case.22

In Steitz v. City of Beacon (295 NY 51 [1945]), the plaintiff’s house was destroyed when, upon the outbreak of a fire, it proved impossible to douse the flames, because the City had negligently failed to maintain the valves and hydrants regulating the pressure. Relying on Moch Co. v. Rensselaer Water Co. (247 NY 160 [1928]), the majority affirmed the dismissal of the complaint. Judge Desmond dissented on the ground that the waiver of governmental immunity effectuated by Court of Claims Act ‘ 8 and the Court’s decision in Bernardine v. City of New York (294 NY 361 [1945]) should apply to the negligent conduct of the fire department. Judge Desmond continued on this theme later as Chief Judge in his lone dissent in Motyka v. City of Amsterdam (15 NY2d 134 [1965]) stating: “[t]he time has come to remove from our law all the remaining vestiges of governmental immunity. We should be done with exceptions and incongruities. . . . Cities should be held to the same standards of conduct as apply to private persons, since the risk of liability (and insurance against the risk) is incidental to municipal activities.”23

Morever, Judge Desmond either wrote or was solidly in support of the majority of the Court in the development of the law of warranty, putting to bed any remnants of the ancient doctrine of privity in cases like Greenberg v. Lorenz (9 NY2d 195 [1961]), Randy Knitwear, Inc. v. American Cyanamid Co. (11 NY2d 5 [1962]) and Goldberg v. Kollsman Instrument Corp. (12 NY2d 432 [1963]).

In a decision that cannot be easily characterized as either liberal or conservative, Judge Desmond was instrumental in writing a landmark opinion for the Court in the conflicts of law field. Kilberg v. Northeast Airlines (9 NY2d 34 [1961]) is generally regarded as the central building block upon which all of New York’s modern conflicts of law jurisprudence is built because it is expressly built on an “interests analysis” instead of a more formalistic approach.

Interestingly, during the years Judge Desmond served as an Associate Judge, he engaged in other outside activities besides his writing projects and teaching duties. Slightly after World War II, Judge Desmond advised the United States Atomic Energy Commission on legal affairs.24 In 1951, he was named chairman of a new Defense Production Administration Committee that was to scrutinize the effect of special tax concessions to industry on the negotiation of defense contracts.25

Court Years as Chief Judge

As Chief Judge, Desmond wielded a powerful presence in the Conference Room. Desmond, according to Judge Stanley Fuld, urged “his views upon his associates fervidly and persuasively, eager to have them prevail, but always willing to modify his positions when discussion engender[ed] doubt.”26 Judge John Van Voorhis said “when the conflicts in thought and experience that go into the fashioning of the law were over,” Chief Judge Desmond could “unfailingly eat and drink with his judicial colleagues as friends.”27 Judge Kenneth Keating called Chief Judge Desmond’s presence in the Conference Room “dynamic, but never domineering. [He kept] order among seven men of rather determined views whose arguments in the conference room were often more heated than those in the courtroom.”28

During this period, the Judges dined most frequently at the Fort Orange Club, an exclusive men’s club, immediately to the west of the State Capitol. Chief Judge Desmond would enjoy a before-dinner highball, preferably scotch, and sometimes a post-dinner cigar. Dinner time was relaxed; the Judges talked about football, the weather, and other light subjects, but tried hard to keep the Court’s work out of the conversation.

As Chief, Judge Desmond’s interests gravitated toward judicial administration, sometimes taking controversial stands. For example, the Judge tried for many years to abolish jury trials in civil cases, a move he was confident would unclog court calendars.29 He supported a merger of all trial courts, calling the Court of Claims “a historic accident.”30 He also spoke of judicial reform when he left the Court in 1966, observing with the wisdom of personal experience:

“the present caseload is far too heavy for this seven member court. Those who are expert at judicial statistics say that a court like ours should not be burdened with more than 25 to 35 cases per judge per year. Here, the average per judge is more than twice that-and ever growing.”31

Within the area of criminal law, Chief Judge Desmond remained keenly cognizant of defendants’ rights. In People v. Donovan (13 NY2d 148 [1963]), the Chief Judge joined the majority in holding that a written confession taken from a defendant in a police station after his lawyer had been refused access to him was inadmissible and a violation of the defendant’s state constitutional right to the effective assistance of counsel. Most notably, he authored People v. Huntley (15 NY2d 72 [1965]) which implemented Jackson v. Denno (378 US 368 [1964]) addressing the voluntariness of confessions and what sort of remedy should be available for those imprisoned based on convictions that had been predicated upon confessions put to a jury without any prior factual finding of voluntariness by a judge. Huntley was a major broadening of the availability of state post-conviction remedies in New York and gave Chief Judge Desmond strong grounds on which to rest his attacks on the widespread use of federal habeas corpus review to “second guess” state appellate court review of criminal convictions.32

Although Judge Desmond never voted to declare New York’s death penalty unconstitutional, he did become satisfied as a policy matter that the death penalty should have been abolished. According to the Buffalo Evening News, Judge Desmond stated: “I question the state’s right to take human life. I doubt that it [the death penalty] acted as a deterrent. And only a relatively few persons sentenced to death paid the supreme penalty.”33

Post Court Years

Judge Desmond’s retirement from the Court at age 70 on December 31, 1966 did not mark the end of his public life. In 1967, he was the only delegate to the State Constitutional Convention elected with a Democratic and Republican endorsement. At the Convention, he led an unsuccessful effort to add an anti-bugging amendment to New York’s Bill of Rights. “I predict that this convention, which holds in horror the secret police, will continue a practice that is characteristic of totalitarianism everywhere. . . . Wiretapping is an excuse for lazy police work,” he said.34 Judge Desmond called wiretapping “a dirty business, revolting business, abhorrent business. This practice is destructive of one of the basic rights for which our forefathers died.”35

Judge Desmond also continued to teach at Cornell Law School, a position he first accepted in 1957. When the Court was not in session, the Judge would travel to Ithaca one day a week and teach a course on appellate advocacy.36 After retirement, he also served as a lecturer in appellate practice at the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Law and continued to teach at a summer seminar at New York University for appellate judges from across the country.

Judge Desmond also served as Chairman of the Canisius College Board of Trustees (he was the first layman so chosen), as a member of the Board of Editors of the New York Law Journal, as co-campaign chairman for Arthur Goldberg-the former Justice of the Supreme Court of the United States-in his run for Governor in 1970, and as a frequent arbitrator in labor disputes. According to the Buffalo News, Judge Desmond “gave [former New York State Governor Mario] Cuomo a strong and politically important endorsement in the primary contest for the Democratic nomination for Governor in 1982 when Cuomo upset New York City Mayor Edward I. Koch, the endorsed candidate.”37

Tributes and Honors

Obviously, one would expect many tributes for any Judge who sat on the state’s highest court for as long as Judge Desmond, but the sheer amount and depth of the praise for the man is overwhelming. According to one commentator, “[f]ew appellate judges enjoy more genuine popularity and more affectionate esteem than the friendly, even tempered, unassuming and plain spoken Chief Judge of the State of New York.”38 At Chief Judge Desmond’s retirement, Judge Stanley Fuld, who would soon be installed as Chief Judge, observed in part:

Chief, you came to the Court as a young man some 26 years ago and you step down from the bench today still a young in heart, vision and mind, notwithstanding that along the way you have acquired in years the Biblical three score and ten. You have served on the Court with e?clat and distinction, longer than any of our predecessors, and yet you still retain the priceless attributes of talented youth-a keen intellect, tireless energy and infectious enthusiasm. To this Court and our consultations you have brought not only dedication and skill but also rare wisdom and fresh insights, the products of your firmly held and oft expressed belief that the dictates of common sense are compatible with the principles of the common law39

The praise from his colleagues on the bench was unanimous. Judge Adrian Burke keenly described the Judge’s strength of character, observing that in Judge Desmond’s

legal endeavors there is no loss of individuality-no enlistment in the mass movements of the particular moment. He is neither vague nor casual, and his work will always be a living reflection of what he thinks and what he cherishes. Untouched by the success he has achieved, through the years he has remained his unique self, exploring ways to express his attitudes toward life and the world around him in his own fashion.40

Former Presiding Justice of the Appellate Division Michael Dillon said:

This remarkable, unique man of four score and ten years never grew old, even as his body gave way to the years. He was ever young and up to date, whether the subject be law, politics or other current events. He lived not in the past, except to apply its experience to the present and the future. He spoke often and reverently about his parents and the politics he learned from his father. He exuded paternal love when he spoke of his children and he reveled in the accomplishments of his grandchildren.41

United States Supreme Court Justice William Brennan described the qualities possessed by Judge Desmond in this way: “massive common sense, downright forcefulness, and obvious lack of subtlety and an abiding instinct for fair play.”42 Governor Mario Cuomo, who knew the judge well from his days as a law clerk to Judge Adrian Burke, praised Judge Desmond in a testimonial held in April 1986, calling the Judge “a man of extraordinary intelligence, rock-solid judgment and unbending convictions.”43 He characterized the witty Judge Desmond as blessed with “a quick and incisive mind and a pleasant sense of humor . . . [He was] a man with a love of people and integrity of person and purpose.”44

Judge Desmond was the recipient of 13 honorary degrees from colleges and universities across the country.45 The Judge received a citation for distinguished service to the legal profession from the University of Buffalo in 1954. He was the winner of the National Conference of Christians and Jews “Brotherhood Award” in 1955 and recipient of the New York State Bar Association’s prestigious Gold Medal Award in 1967.

Judge Desmond died on February 9, 1987 in Mercy Hospital after a brief illness. Just the Wednesday before his death, Judge Desmond finished teaching a course at the State University of New York at Buffalo School of Law. Memorial exercises were held at the Court of Appeals on February 10, 1987. Chief Judge Wachtler expressed the deepest sympathy of the Court to his family as it remembered him in thoughts and prayers. Judge Desmond is buried in the Immaculate Conception section of the Eden Evergreen Cemetery in Eden, New York.

Progeny

Judge Desmond was survived by three daughters and 12 grandchildren. Daughters: Sheila Landon (children Peter Cook Landon, Timothy Landon, Patrick Desmond Landon [deceased], Christopher Landon [deceased]); Kathleen Hughes (children Bridget Trimboli, Maura Bowman and Desmond Hughes); Patricia Williams (children: Amelia Williams, Gregory Williams, Edward Williams). Judge Desmond’s only son, Charles Ryan Desmond (known as Ryan), died tragically in a car accident in 1985. He was survived by four children: Charles S. Desmond II, Julie Schechter, Joseph Desmond and Mollie Scanlon.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

(In addition to all of the Judges’ Published Writings

and the sources listed in the biography endnotes)

Biographical File at the University Archives, State University of New York at Buffalo – consisting of many newspaper articles from Buffalo New York Newspapers, including, but not limited to, many articles cited in the endnotes to the biography.

Charles S. Desmond, A Quarter Century Service to New York and The Nation, 15 Buffalo L Rev 253 (Winter 1965). This entire volume contains tributes by William J. Brennan Jr., Sir George Coldstream, Stanley H. Fuld, and Ray Forrester, and the following articles within the overall heading The Path of New York Law: 1945-1965:

Bergan, The New York Court of Appeals.

Laufer, Tort Law.

Paulsen Criminal Procedure.

Karlen and Harris, Judicial Administration.

Hyman, Home Rule.

Desmond, Appeals under Election Law, NY Times, Jan. 9, 1965, at 36.

In Memoriam: Remarks by Sol Wachtler, Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals on the Death of Former Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, 69 NY2d VII.

1965 New York “Redbook.”

Remarks at Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond,18 NY2d VII.

Taylor, Eminent Members of the Bench and Bar of New York (1943).

A Tribute to Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, 52 Cornell LQ 351 (Winter II 1967), includes the following two articles:

Van Voorhis, Chief Judge Desmond and the New York Court of Appeals.

Thoron, Chief Judge Desmond and Cornell.

Van Voorhis, Burke, Scileppi, Bergan, Keating,

Charles S. Desmond-Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals-A Tribute, 8 St. John’s L Rev 8-17 (1967).

Published Writings

Books:

Through The Courtroom Window, West Publ. Co. (1959).

Sharp Quillets Of The Law, From Decisions of The New York Court of Appeals, Dennis & Co. (1949).

Articles, Book Reviews, and Forwards To Other Works:

A Tribute to Thomas Headrick, 34 Buffalo L Rev 631 (1985).

Dedication: A Tribute to Adolf Homburger, 26 Buffalo L Rev 209-218 (1977).

Dedication: A Salute to Joseph Laufer, 28 Buffalo L Rev 447 (1977).

Tribute to Maurice H. Frey, 24 Buffalo L Rev 265 (1974-1975).

A Tribute to Judge Adrian P. Burke (with others), 48 St. John’s L Rev 437 (1974).

Faculty Memorial for Dr. Harold F. McNeice, 47 St. John’s L Rev VII (1973), Reprinted in 19 Cath Lawyer 5 (1973).

A Memorandum as to the Constitutionality of the so-called “Gordon No-Fault Automobile Insurance Reparations Bill” (1972) (available in New York State Library)

Proposals for Judicial Reform in New York, 36 Brooklyn L Rev 329 (1970).

Mr. Justice Jackson: 4 Lectures in His Honor (with Paul A. Freund, Justice Potter Stewart, and Lord Shawcross) (Colum Univ Press 1969).

May It Please the Committee, 22 Record of the Association of the Bar of the City of New York (Republished 39 Oklahoma Bar Assn. J. 1177 [1968]).

Lawyers, 53 Cornell L Rev 547 (1967-1968).

Courts Judges and Constitutional Reform, 39 NYS Bar J 285 (1967).

After 26 Years on the Court of Appeals, 42 St. John’s L Rev 5 (1967).

Twenty Six Years, Twenty Six Cases, 24 NY County Bar Bulletin 24:147 (1966-1967).

Reflections of a State Reviewing Court Judge Upon The Supreme Court’s Mandates in Criminal Cases (combined with other articles in a symposium on The Supreme Court and the Police, 57 Journal of Crim Law 238 [1966]).

Courts, The Public and the Law Explosion: A Critique, 54 Georgetown LJ 777 (1966).

Appreciation of Judge Marvin Dye, 51 Cornell LQ 151 (1965-1966).

Current Problems of State Court Administration, 65 Colum L Rev 561 (1965).

Advance and Change in the Law, 32 Tenn L Rev 18 (1964-1965).

What the Courts Expect of Bar Examiners, 33 Bar Exam 38 (1964).

Federal Habeas Corpus Review of State Court Convictions, 9 Utah L Rev 18 (1964).

Juries In Civil Cases-Yes or No, 36 NYSBJ 104 (1964).

Forward to Francis Gary Power’s Book Strangers On A Bridge: The Case of Colonel Abel, Atheneum (1964).

Memoriam To Justice Phillip Halpern. Logic, Liberalism and The Convention of 1938: Phillip Halpern’s Role (with other tributes), 13 Buffalo L Rev 303 (1964)

Federal Habeas Corpus Review of State Court Convictions (with other articles on Judicial Review), 50 Georgetown LJ 653 (1962).

Book Review of Karl Llewellyn’s Common Law Tradition: Deciding Appeals, 36 NYU L Rev 529 (1961).

Integrate the New York Bar?, 13 Syracuse L Rev 201 (1961).

Musings, 54 Law Lib Journal 29 (1961).

Current Court Problems (with other authors), 19 NY County Bar Bull 132 (1961).

Copyright Symposium, Forward, 11 Copyright Law Sym (1960).

Some Major Proposed Changes in the Civil Practice Act (with other authors) 32 NYS Bar Bull 313 (1960).

Some Civil Rights Cases in the New York Court of Appeals, 22 Rocky Mountain L Rev 1 (1959-1960).

Albert Conway-Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals, A Tribute, with C.W. Froessel, C.A. Keeler, G. Goodnough & J.P. McGrath, 34 St. John’s L Rev 1 (1959).

Desmond, A Modern Day Law Guild, 140 NYLJ No. 44, P2 (October 19, 1958).

Free Speech and Obscenity, Reprinted in 1958 Joint Legislative Committee To Study the Publication and Dissemination of Offensive and Obscene Material, Legislative Documents Series N 130.

Book Review of N. St. John-Stevas’s Obscenity and the Law, 32 Notre Dame Law 547 (May 1957).

The Formation Of The Law: The Interrelation of Decision and Statute, 26 Fordham L Rev 217 (1957).

University of Detroit Law Journal’s 40th Anniversary Messages of Felicitation: Why A Law Review, 34 U Det LJ 247 (December 1956).

Slow Process Toward A Speed Up, 8 Brooklyn Bar 5 (October 1956).

Legal Problems In Censoring The Media of Mass Communications, 40 Marquette Law Rev 38 (1956).

Idea Of A Law School, 1 Vill L Rev 5 (January 1956).

Natural Law and the American Constitution, 22 Fordham L Rev 235 (1953).

Censoring the Movies, 29 Notre Dame Lawyer 27 (1953).

Practical Problems of the Courts, 19 Ins Counsel J 270 (1952).

Bail-Ancient And Modern, 1 Buffalo L Rev 245 (1952).

Where Have the Litigants Gone, 20 Fordham L Rev 229 (1951).

Arising Out of And In The Course of Employment In New York, 26 Notre Dame Lawyer 462 (1950-1951).

The Limited Jurisdiction of the New York Court of Appeals B How Does It Work? (a comparison between 1948-49 and 1923-1924), 2 Syracuse L Rev 1507 (1950).

Book Review of James Willard Hurst’s, Growth of American Law: The Lawmakers, 26 Notre Dame Law 169 (1950).

How Many Kinds Of Courts Do We Need, 21 NYSBA Bull 442 (1949).

The Annulment Problem (Address), 20 NYSBA Bull 59 (1948).

The Soldier-Lawyers Return To Practice (Address), 67 NYSBA 362 (1944).

Forfeiture Of Vessels In Enforcement of National Prohibition, 11 ABA J 21 (1925).

Endnotes

- Great luminaries of the law such as John Jay and James Kent can lay claim to the title of Chief Judge of the State of New York, but they were not Court of Appeals Judges because the Court of Appeals was not created until 1847 (see There Shall be a Court of Appeals, 150th Anniversary of the Court of Appeals of the State of New York, Booklet on File with Author). However, on September 1, 1962, pursuant to a new Court reorganization statute, the Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals became the Chief Judge of the State of New York (see Judiciary Law ‘ 210; see also NY Const Art VI, ” 1, 28).

- Judge John Van Voorhis, a contemporary of Judge Desmond from Rochester, was fond of telling this story:

“It need hardly be said that Chief Judge Desmond is a vivid personality. He exhibits undiminished the flair brought from County Cork in Ireland by his grandfather, who, following an altercation with his boss on the railroad, declared that never again would he work for anybody else and never did.”

(A Tribute to Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond: Van Voorhis Chief Judge Desmond and the New York Court of Appeals, 52 Cornell LQ 351, 352). - For the information on Judge Desmond’s accomplishments and activities at Canisius, I am indebted to the research work of Elizabeth Higgins, the Acting Director of Archives and Special Collections, Canisius College.

- Judge Desmond also obtained an LL. D. degree from Canisius College in 1942.

- See Desmond Named to Judicial Post, Buffalo Evening News, Jan. 6, 1941.

- At the time of his appointment to State Supreme Court by Governor Lehman in 1940, Judge Desmond was a trustee of the County Bar Association, and a member of the American Bar Association, the New York State Bar Association, the Knights of Columbus, Canisius College Alumni Association, Board of Governors of the Catholic Diocese of Buffalo and Phi Delta Phi Fraternity (see id.).

- Judge Desmond no doubt borrowed the title from Shakespeare’s King Henry VI, Act II, Scene 4: “But in these nice sharp quillets of the law, good faith, I am no wiser than a daw.” (see 83 Law Cases Put into Popular Book by Judge Desmond, Buffalo Evening News, Feb. 24, 1949).

- Desmond, Through the Courtroom Window, at 181-186 (West Publishing [1959]).

- Id. at 186.

- Id. at 188.

- New Form of Isolationism Appearing, Desmond Warns, Courier Express, Mar. 29, 1943.

- Catholic Attorneys Urged to Organize, Buffalo Evening News, Sept. 23, 1945.

- Id.

- Id.

- Desmond, Natural Law and the American Constitution, 22 Fordham L Rev 235, 242-243 (1953).

- Remarks on Retirement of Chief Judge Conway, 7 NY2d viii.

- http://wings.buffalo.edu/law/bmcb/desmond.htm last accessed January 1, 2006.

- Charles Desmond, Retired Chief Judge, Dies, NY Times, Feb. 11, 1987, at B12.

- Other criminal law cases that illustrate Judge Desmond’s concern for a fair process and the rights of defendants include his early decision to join Judge Loughran’s dissent in People v. Buchalter (289 NY 181 [1942]), and his decision to join the majority in People v. Leyra (302 NY 353 [1951]), and People v. Waterman (9 NY2d 561 [1961]). According to Judge Stanley Fuld, Judge Desmond was “an outspoken champion of the right of every defendant to procedural safeguards provided by constitution, statute and the rules of evidence.” (Fuld, Charles S. Desmond: A Judge for the Changing Years, 15 Buffalo L Rev 258, 260 [1965]).

- 4 NY2d at 365-366 (asterisks in original).

- Desmond, Legal Problems Involved in Censoring the Media of Mass Communication, 40 Marquette L Rev 38, 38, 56 (1956). For more details on Judge Desmond’s views toward the regulation of obscene works, see Desmond, Censoring the Movies, 29 Notre Dame Lawyer 27, 35-36 (1953) (“Freedom of expression has duties as well as rights, and when those rights are violated, in a real and substantial way so as to outrage the basic moral code, government has, I think the constitutional as well as the moral right to stop the evil at its source, and need not wait and punish after the harm has been done.”)

- 303 NY at 354-355.

- 15 NY2d 141.

- Judge Desmond Confers on A-Bomb in Capital, Courier Express, July 13, 1947.

- Desmond Selected to Direct a Study of Tax Writeoffs, Buffalo Evening News, Oct. 23, 1951

- Fuld, Charles S. Desmond: A Judge for the Changing Years, 15 Buffalo L Rev 258, 260 (1965).

- Van Voorhis, Chief Judge Desmond and the New York Court of Appeals, 52 Cornell LQ 351, 353 (1967).

- Keating, Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, A Tribute, 42 St. John’s L Rev 17 (1967).

- See Desmond, Juries in Civil Cases-Yes or No, 36 NYSBJ 104 (1964).

- Merger of Trial Courts Urged, Courier Express, June 13, 1967.

- Remarks at Ceremony Marking Retirement of Chief Judge Charles S. Desmond, 18 NY2d ix.

- See Desmond, Federal Habeas Corpus Review of State Court Convictions- Proposals for Reform, 9 Utah L Rev 18 (1964); see also Desmond, Federal Habeas Review of State Court Convictions, 50 Georgetown LJ 755 (1962).

- Judge Desmond-A Man of Sympathy, Wit, Intellect, Buffalo Evening News Magazine, May 28, 1966, at B1.

- Desmond-Led Effort to Ban Wiretapping Fails at Convention, Buffalo Evening News, Aug. 31, 1967.

- Id.

- Judge Desmond taught the appellate advocacy half of Trial and Appellate Advocacy for a decade at Cornell Law School, beginning as a Lecturer in Law and finishing with the title of Visiting Professor of Law. As noted by his teaching collaborator, Gray Thoron, “Judge Desmond possesse[d] a rare combination of charm, wit, enthusiasm and zest for life. He can perhaps be best described as belonging to that rare company of those who remain, no matter how inexorably the calendar rolls on, perpetually young in spirit.” (Thoron, Chief Judge Desmond and Cornell, 52 Cornell LQ 354, 355-356 [1967]). Professor Thoron noted that he could not remember Judge Desmond missing a single class in his ten years of teaching while he was still a Court of Appeals Judge. “When adverse weather condition on occasion grounded his plane, he carefully traveled to and from Ithaca by car, no matter how treacherous the driving conditions.” (id. at 355).

- Charles S. Desmond is Dead at 90, State’s Chief Judge, Buffalo News, Feb. 10, 1987, at 1).

- Laufer, Tort Law in Transition: Charles S. Desmond’s Quarter Century on the New York Court of Appeals, 15 Buffalo L Rev 276 (1965).

- 18 NY2d vii.

- A Tribute by Judge Adrian Burke, 42 St. John’s L Rev 10 (1967).

- Tribute to Charles S. Desmond, http://wings.buffalo.edu/law/bmcb/desmond.htm last accessed January 6, 2006.

- Brennan, Chief Judge Charles Desmond, 15 Buffalo L Rev 253, 253 (1965).

- Charles S. Desmond is Dead at 90, State’s Chief Judge, Buffalo News, Feb. 10, 1987, at 1).

- Id.

- Among the institutions that awarded Judge Desmond honorary degrees are New York University, Syracuse University, Villanova University, Canisius College, the State University of New York at Buffalo, St. John’s University, Brooklyn Law School, Niagara University, Iona University and the University of Notre Dame (see Judge Desmond is Looking for New Jobs to Conquer, Buffalo Evening News, Mar. 17, 1966, at 41; Judge Desmond Honored at Notre Dame, Buffalo Evening News, June 5, 1967).