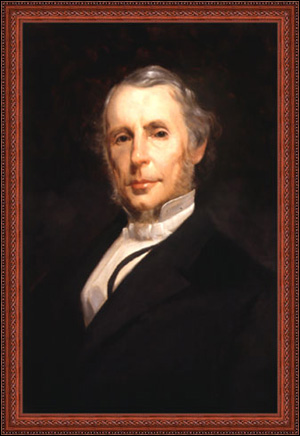

Lawyers who know their way around the books will likely associate the name Comstock with “Comstock’s Reports” and with good reason: he was the State’s first official Reporter, after the office was created by the 1847 Judiciary Act. He went on to become a Judge of the Court of Appeals and eventually its Chief.

Judge Comstock’s father, Serajah Comstock, a native of Litchfield, Connecticut, served in the Revolutionary War and was at the battle of Bunker Hill. Following the British surrender at Yorktown, Serajah and his wife settled on a farm near Williamstown, Oswego County, where Judge Comstock was born, on August 24, 1811. Judge Comstock received his early education in the local public schools. He was only 14 when his father died, leaving him to earn his own living. Interested in scholarship from an early age, Judge Comstock taught school, briefly attended Ellisburg Academy in nearby Jefferson County and, through industry and perseverance, managed to save enough money to enter Union College in April 1832. During the tenure of Dr. Eliphalet Nott as college president, young Comstock attended Union college and graduated with high honors in 1834. Judge Comstock was a Sigma Phi while at Union and was later elected to Phi Beta Kappa.

Following his graduation from Union, Comstock obtained employment as an instructor in the classics at a private school in Utica, New York. In his spare time, he studied law and soon moved to Syracuse, where he continued his legal studies as a clerk in the law firm of Noxon and Leavenworth. His preceptor, Bartholomew Davis Noxon, was among the most distinguished attorneys in New York State. Noxon’s partner, Elias W. Leavenworth, became well known as New York State Secretary of State and as a member of the Forty-fourth Congress. On his admission to the bar in 1837, Comstock became a partner in the firm. In 1839, he married his mentor’s daughter, Cornelia Noxon, with whom he later had a son and an adopted daughter.

Over the ensuing decade, Comstock developed a State-wide reputation for legal excellence. In 1847, Governor John Young appointed him State Reporter, a position he occupied for three years, during which time he published the first four volumes of the New York Reports. Comstock was the first Reporter to officially hold the title of State Reporter, which was created by the Judiciary Act of 1847. During his tenure as State Reporter, Comstock actively pursued the private practice of law and helped organize the Syracuse Savings Bank, serving as one of its incorporators.

In 1852, President Millard Fillmore, a moderate Whig and former New York State Secretary of State, named Comstock Solicitor of the United States Treasury, a position he occupied until Franklin Pierce, a New Hampshire Democrat, became President in 1853. By the mid-1850s, deep fissures had developed within the Whig party. In 1855, the conservative Whigs, known as the “Silver Grays,” in conjunction with the “native American” party, nominated Comstock for election to the Court of Appeals. In November of that year, the 44-year-old Comstock was elected, succeeding Judge Charles H. Ruggles (1789-1855), who had resigned due to illness.

Judge Comstock served on the Court for five years, the last two, 1860 and 1861, as Chief Judge. His opinions, which were known for their logic, detail, precision of expression, and explication of abstruse legal propositions, appear in the 13th through 24th volumes of New York Reports.1 His most famous writings are Wynehamer v. People (13 NY 378 [1856] [striking down the prohibitory liquor law as violative of the New York State Constitution’s due process and jury trial guarantees]) and Curtis v. Leavitt (15 NY 9 [1857] [upholding validity of the North American Trust and Banking Company’s debt obligations, amounting to $1,500,000, held by British creditors]). Also noteworthy is his dissent in Lawrence v. Fox (20 NY 268 [1859]), which represents a paradigmatic example of deductive reasoning and legal formalism. While on the Court, Judge Comstock was selected by Judge Nicholas Hill to divide the old Chancellor’s library and to locate the two portions in Syracuse and Rochester, to serve as the Library of the Court of Appeals.

By the end of Judge Comstock’s tenure at the Court, the nation stood on the brink of civil war. The old Whig party had ceased to exist, and the conservative Whigs had largely joined the Democratic party. In 1861, he ran unsuccessfully for reelection to the Court on the Democratic ticket, losing in a Republican sweep. Though an ardent Unionist, Judge Comstock was sharply critical of President Lincoln and the abolitionist views espoused by the radical Republicans. He rejected the doctrine of secession advocated by Jefferson Davis, reasoning that because the States’ grant of certain enumerated powers to the Federal Government was “irrevocable and perpetual,” the States could not “absolve the citizen from the obedience which he owes to the constitutional powers of the Union.”2 At the same time, he rejected the radical Republican position that the southern States had forfeited their sovereignty by revolting against the Union, reasoning that only individuals, and not States, can be guilty of treason or armed revolt. Judge Comstock decried the idea of waging war against the southern States for the purpose of abolishing slavery:

The Federal Government has no more right to invade one section of the Union for a purpose outside of the Constitution, no more right to propagate by force of arms in one State the theories, sentiments and opinions of other States, than it has to invade the Kingdom of Brazil to abolish slavery, or the Turkish Empire to abolish polygamy.3

Judge Comstock’s views appear to have been animated not by racism, but by his belief in the sanctity of “States’ rights” and limited federal power under the Constitution. Judge Comstock wrote:

[U]nder the Constitution of the United States there is no shadow of right, in peace or war, by its laws or its military power, to spread or to propagate the opinions or sentiments of any class or section, upon social and moral questions.4

Following his service at the Court, Judge Comstock returned to private practice in Syracuse, where he quickly developed a reputation as a consummate equity lawyer. His early return to private practice was in many respects a blessing, for he would achieve his greatest renown as an advocate, arguing nearly one hundred cases on appeal, including 67 cases before the Court of Appeals and seven before the United States Supreme Court. Notwithstanding his immense success as an advocate, however, Judge Comstock generally eschewed jury trials, as he reportedly had little faith in juries.5

In 1865, the heirs of Chancellor James Kent asked Judge Comstock to edit a new edition of Kent’s Commentaries on American Law, a task he approached with alacrity. In his preface to the Eleventh Edition of this celebrated work, Judge Comstock wrote:

In performing these labors I have been more than ever impressed with the accurate and consummate learning of the author, and the great value of his volumes to the student and the profession. My utmost wishes are attained if I have been able to add anything of usefulness to a work already so highly and universally appreciated.6

Judge Comstock was elected a delegate at large to the Constitutional Convention of 1867, where he served with distinction as a member of the judiciary committee, a group which historian Charles Lincoln described as consisting of “fifteen of the most eminent men in the Convention.”7 The judiciary committee undertook the formidable task of reforming the judicial system established under the 1846 Constitution. Under that Constitution, four of the eight Judges of the Court of Appeals were elected by statewide vote; the remaining four were appointed from the class of Justices of the Supreme Court having the shortest time to serve. Lincoln (and others) noted that the system was inefficient and badly in need of reform.8 Judge Comstock took a leading role in the committee’s work and is widely credited, along with Judge Charles J. Folger, as a principal drafter of the new judiciary article. That article, among other things, established a 14-year term for Judges of the Court of Appeals. Notably, the new Judiciary Article was the only one the voters accepted.

The proposed constitution had been strongly opposed by William M. “Boss” Tweed and the Tammany Hall establishment. During its 1869 convention, the state Democratic party formally announced its opposition to the proposed constitution. The Republican party took no official position, leaving the matter to its individual candidates the decision whether to support or oppose its adoption. As a Democratic candidate, Judge Comstock’s support of certain changes intended to reduce political corruption incurred Tammany’s wrath, thus ensuring the defeat of his nomination for Chief Judge.

His political ambitions frustrated, Judge Comstock again returned to a highly prominent, full time law practice in Syracuse. Ironically, when William M. Tweed was later convicted on twelve counts and sentenced to one year in prison on each, he entreated Judge Comstock to represent him in his habeas corpus proceeding. Casting aside prior differences, Comstock agreed to undertake the representation. In what was perhaps his greatest legal feat, Judge Comstock persuaded the Court of Appeals that the trial court acted in excess of its jurisdiction in imposing twelve consecutive sentences and secured a reduction in Tweed’s sentence from twelve years to one (see People ex rel. Tweed v. Liscomb, 60 NY 559 [1875]). Additionally, Commodore Vanderbilt’s son, William H. Vanderbilt, retained Judge Comstock and William Evarts in a will contest.

Judge Comstock’s contributions were not limited to the law. He also devoted significant time and resources to educational and civic causes, and was awarded an honorary degree by his alma mater, Union College. He played a pivotal role in the movement to establish Syracuse University at its present location. The University traces its origins to Genesee College, which the Genesee Methodist Conference established near Lima, New York, in 1849. The fledgling institution struggled financially in its existing location, prompting its Board of Trustees to look for a new home. Judge Comstock spoke out at public meetings and wrote newspaper articles in favor of bringing Genesee College to Syracuse, helping to galvanize public support. As part of the negotiations that brought the college to Syracuse, Judge Comstock gave the college a fifty-acre parcel and a $50,000 contribution toward the establishment of what, in 1870, became Syracuse University. He is said to have been largely instrumental in founding Syracuse University.9 Judge Comstock later served on the University’s Board of Trustees for more than two decades.

In 1872, he purchased the 200-acre Stevens Farm and donated a portion of it to the City of Syracuse for use as a public park. The City named Comstock Avenue is his honor.

Judge Comstock is considered the founder of St. John’s School for Boys in Manlius, New York, toward whose formation he donated $60,000. The school, which was affiliated with the Episcopal Church, provided a military style education. Judge Comstock served as Vice President of the school’s Board of Trustees. Former Chief Judge Folger served alongside Judge Comstock on the Board of Trustees. In addition, Judge Comstock was a trustee of the State Institute for Feeble-minded Children in Syracuse. He was also a member of St. Paul’s Episcopal Church in Syracuse.

In June 1887, Judge Comstock traveled to Saratoga Springs to visit Chief Judge William C. Ruger and while there suffered a severe episode of vertigo secondary to a form of kidney disease. His health never fully returned, but he continued to practice and even argued eight more cases before the Court of Appeals before his death on September 27, 1892, in Syracuse. He was survived by his wife and son. As noted in the Green Bag, even late and in life Judge Comstock “maintained his intellectual vigor to a surprising degree, and his counsel was sought in many important cases up to within a short time of his death.”10

After Judge Comstock’s death, the members of the Onondaga County Bar Association assembled at the courthouse in Syracuse to honor his memory. Judge A. Judd Northrup observed:

For more than half a century the name of George F. Comstock has been recognized as that of one of the giants of his profession. . . . As a lawyer, he delighted in deep study, and profound research. . . . No difficulty, however stupendous, caused him to shrink. . . . Abstruse and intricate propositions of law seemed to be his special province. . . . He was a man of strong convictions; of fiery energy, fearless, and independent, yet the emanations from his brain presented the judicial coldness of marble chiseled by a master hand. . . . The prosperity of the city of his choice and the cause of education were dear to him, and the behests of charity were to him a welcome sound. Truly, a great light has gone out, but a glorious memory abides.11

Progeny

Research has not revealed any descendants of Judge Comstock. None of the sources consulted revealed the name of Judge Comstock’s son, who predeceased him. One biographer, William D. Lewis, states that Judge Comstock had an adopted daughter who survived him but died some time before 1909.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

51 Albany Law Journal 408 (1895).

Bruce, ONONDAGA’S CENTENNIAL: GLEANINGS OF A CENTURY 356 (Boston History Co. 1896).

Comstock, Let Us Reason Together, in 18 PAPERS FROM THE SOCIETY FOR THE DIFFUSION OF POLITICAL KNOWLEDGE (1864).

CONTEMPORARY BIOGRAPHY OF NEW YORK 147-149.

Cookinham, HISTORY OF ONEIDA COUNTY, NEW YORK: FROM 1700 TO PRESENT TIME 515 (S.J. Clarke Pub. Co. 1912).

4 DICTIONARY OF AMERICAN BIOGRAPHY 332-333 (1930).

2 Green Bag 283 (1890), at http://www.heinonline.org.

4 Green Bag 548 (1892), at http://www.heinonline.org.

1 HISTORY OF THE BENCH AND BAR OF NEW YORK 285 (New York History Co. 1897).

Kent, COMMENTARIES ON AMERICAN LAW (George F. Comstock ed., Little, Brown, and Company 11th ed. 1867).

Letter, February 17, 1849, from Judge Comstock to Assemblyman Joseph Slocum, urging support for the passage of a bill to locate the Chancellor’s library in Syracuse rather than Rochester (letter in Court of Appeals archives).

Lewis, Great American Lawyers, Vol. VI, Philadelphia, John C. Winston Co., 1909, p. 197, biographical essay by Thaddeus David Kenneson.

2 Lincoln, CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OF NEW YORK 247-248 (The Lawyers Co-Operative Pub. Co. 1906).

13 NATIONAL CYCLOPEDIA OF AMERICAN BIOGRAPHY at 151.

New York State Bar Association Report (1893), p. 130.

New York State Law Reporting Bureau, But how are their decisions to be known? at http://www.courts.state.ny.us/reporter/History/page27.htm.

Judge Comstock’s Illness, N.Y. Times, June 30, 1887, at 1, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Obituary, N.Y. TIMES, September 28, 1892, at 5, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Onondaga County Bar Association, The History of the Onondaga County Bar Association, at http://www.onbar.org/about/history.htm.

Strong, Landmarks of a Lawyer’s Lifetime (1914), pp. 228-240.

Syracusan, Vol. 15, No. 2, Oct. 3, 1891, p. 23.

Historical Background: Syracuse University Campus, at http://www.syracusethenandnow.net/Dwntwn/SU/History/SUHistory.htm.

“There shall be a Court of Appeals . . .” at http://www.courts.state.ny.us/history/elecbook/thereshallbe/pg13.htm.

The Tweed Habeas Corpus, New York Times, March 25, 1875, at 12, in ProQuest Historical Newspapers.

Union College records.

University Neighborhood Preservation Association, A Brief History of the Southeast University Neighborhood, at www.unpa.net/neighborhood/history.htm

Published Writings Include:

Speech delivered at Syracuse, N.Y. (August 1, 1868) (Crisis Print 1868).

Kent, COMMENTARIES ON AMERICAN LAW (George F. Comstock ed., Little, Brown, and Company 11th ed. 1867).

Let Us Reason Together, in 18 PAPERS FROM THE SOCIETY FOR THE DIFFUSION OF POLITICAL KNOWLEDGE (1864).

Endnotes

- 51 ALBANY LAW JOURNAL 408 (1895), at http://www.heinonline.

com. - Comstock, Let Us Reason Together, in PAPERS FROM THE SOCIETY FOR THE DIFFUSION OF POLITICAL KNOWLEDGE (1864), at 6-7.

- Id. at 2.

- Id. at 5.

- 4 Dictionary of American Biography 332-333 (1930).

- Comstock, Preface to Kent, COMMENTARIES ON

AMERICAN LAW (George F. Comstock ed., Little, Brown, and

Company 11th ed. 1867). - 2 Lincoln, CONSTITUTIONAL HISTORY OF NEW YORK 248

(The Lawyers Co-Operative Pub. Co. 1906). - Id.

- 4 Green Bag 548 (1892).

- Id.

- Memorial, October 15, 1892.