This article was written by Dr. Julia Rose Kraut. Dr. Kraut is the inaugural Judith S. Kaye Teaching Fellow and taught “Civil Rights, Civil Liberties, and the Empire State” on the BHSEC Queens campus in spring of 2017. She also taught an adapted version to eighth graders at George Jackson Academy. She is a legal historian living in New York City and earned her J.D. from American University Washington College of Law and her Ph.D. in History from New York University. Julia is currently writing a book on the history of ideological exclusion and deportation in the United States, which is under contract to Harvard University Press.

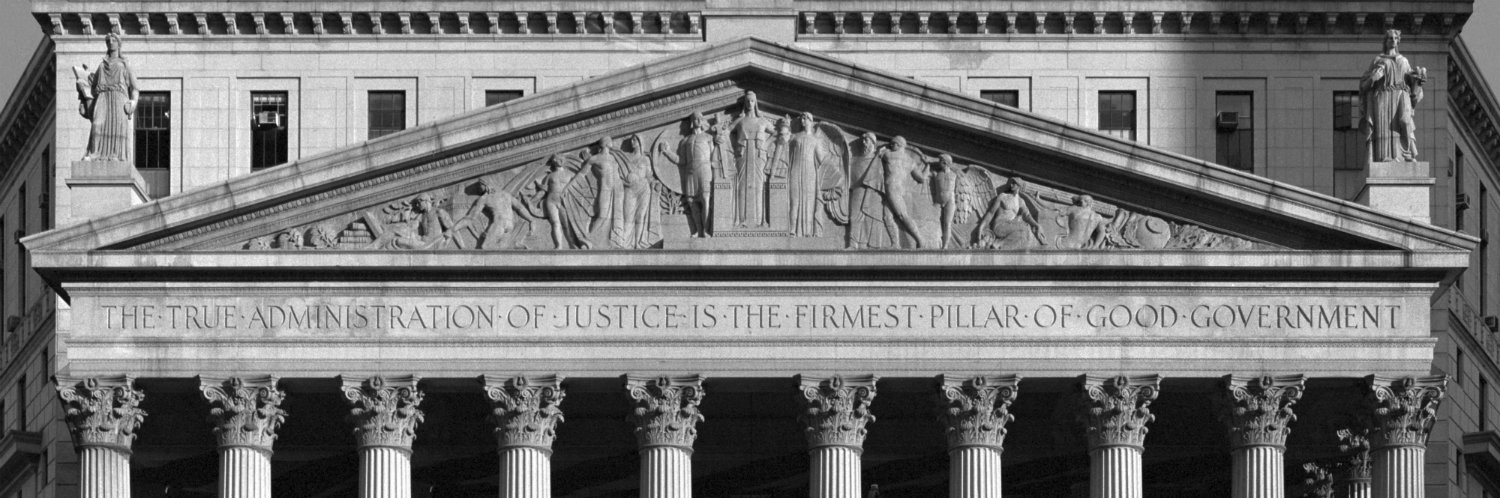

Photo: New York County Courthouse

In my last blog post, I recounted meeting Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye when I was an undergraduate student at Columbia University, and how this chance meeting inspired me to pursue my interest in law and history and become the inaugural Judith S. Kaye Teaching Fellow for the Historical Society of the New York Courts. I also discussed the course I developed for the Society, “Civil Rights, Civil Liberties, and the Empire State,” and teaching this course at Bard High School Early College in Manhattan in Spring 2016. In this blog post, I would like to describe my experiences teaching this same course to students at Bard High School Early College in Queens in Spring 2017.

The semester began the first week of February, shortly after President Donald Trump’s inauguration, and it ended in early June. Those four and a half months proved to be an incredibly turbulent period for the nation, and one that presented many challenges, as well as many teachable moments that demonstrated the importance of studying law and history. At breakneck speed, each week appeared to bring many of the course’s themes to the forefront of the public’s attention. Newspapers, social media, and cable television news programs were filled with discussion and debate on the important function of each branch of government and the limits on the power exercised by each branch, the rule of law, federalism, immigration and nativism, freedom of speech and of the press, as well as the role of public protest, legislation, and the courts in civil rights and civil liberties history.

My class consisted of a great group of hard-working students who brought their questions, concerns, and personal experiences to the classroom. It was a small group, but a diverse one. The students all came from different backgrounds, economic statuses, races, sexual orientations, religions, ethnicities, and neighborhoods in New York City. Each student provided a unique perspective on the cases and controversies we discussed in class. All expressed a desire to learn more about civil rights and civil liberties legal history to better understand how this history had shaped their lives and led to political and social change.

In the first two weeks of class, one of my students organized a teach-in to discuss freedom of speech issues on and off campus and President Trump’s travel ban. I accepted her invitation to participate in the teach-in, and, in my remarks, I provided historical context and a legal perspective on immigration and freedom of speech restrictions, while discussing relevant legal precedent and doctrine. I was happy to see that my student had taken the time to organize this event for her classmates and had reached out to faculty to assist her. The teach-in not only offered additional information to students and faculty, but it also presented an opportunity to show the value of teaching legal history in high schools and how a Judith S. Kaye Teaching Fellow could contribute to learning inside and outside of the classroom.

The spring semester brought more litigation and court decisions, large public protests and new resistance movements, and a number of executive orders, firings of government officials, and tweets from President Trump. My students came to each class with questions and concerns about what they had read or watched. My approach to teaching has always been to show how studying the past and legal precedent could help to illuminate the present and to shape the future, as well as to show how what students learn in the classroom is relevant to their everyday lives. While my course curriculum and approach to teaching remained the same, I had to make a few adjustments to address my students’ questions and concerns and to help us keep up with a fast-paced news cycle.

Each week, I set aside time to discuss the news. These brief sessions provided students with the opportunity to ask questions and express their thoughts on current events, and they provided me with the chance to answer their questions, fill in gaps, and explain historical comparisons to President Richard Nixon and the Watergate scandal (both unfamiliar to many students). I was also able to incorporate students’ interests into class lessons. As my students learned how to read law and to interpret legal precedent, I posted links to arguments and court decisions on the travel ban for students who wanted to follow the litigation. Students not only had the chance to hone their analytical skills, but also to become more comfortable reading legal documents in cases that were important to them.

As the course progressed, the civil rights and civil liberties history and the legal precedent that we discussed in class carried a new significance and a remarkable relevancy. After reading the Declaration of Independence and the Constitution, students found our conversations about checks and balances, the limits of executive power, the role of the judiciary, and freedom of the press echoed in newspaper editorials and on television. Our readings on slavery and abolitionism in the nineteenth century, New York law in Lemmon v. People (1860) and its conflict with federal law in Dred Scott v. Sandford (1857), all resonated with current discussions and questions concerning federalism and immigration, as well as protests over deportations of undocumented immigrants and conflicts over sanctuary cities. Students who donated money to Planned Parenthood were now excited to learn about its founder, Margaret Sanger, and her fight for reproductive rights in the New York courts.

At the end of an exhausting semester, my students told me how much they appreciated the opportunity to take this legal history course and connect law and history with the present. They found the law to be a useful lens to view the past, and that learning to read and understand legal precedent influenced their activism and provided a fresh perspective on contemporary political and social issues. They insisted that every student should learn about the legal foundations behind their civil rights and civil liberties, and they hoped the Judith S. Kaye Teaching Fellowship would continue. I was delighted when I heard from students who took what they had learned in the course and had used it outside of our classroom. One student told me how much she loved reading the court decisions, and that she had read more on her own. Another student beamed as she proudly recounted how she was the only one who recognized a court case mentioned in another class and had described it to her classmates. I was thrilled when my students’ parents told me that their children now discussed legal precedent and history when talking about current events around the family dinner table.

It has been an honor to be the inaugural Judith S. Kaye Teaching Fellow. I will always be grateful to the Historical Society of the New York Courts for the opportunity to help students to learn how history, the law, and the courts affect their lives and the lives of others. When I reflect on Spring 2017, I will not only think of the many executive orders, protests, investigations, travel bans, litigation, and deportations, but I will also think of the many teachable moments.

Comments · 1

Comments are closed.