Eddie Roth was a law clerk to Chief Judge Lawrence H. Cooke from 1982-84. He and fellow law clerk Jeanne Philips-Roth married in 1987. He now serves as a legal advisor to the St. Louis Metropolitan Police Department. He originally published this essay for friends and family on his Facebook page in September 2014, as a centennial tribute to Chief Judge Cooke.

October 15 marks the 107th anniversary of the date of New York Chief Judge Lawrence H. Cooke’s birth. He was a jurist of great distinction, and a person of unsurpassed decency, integrity and good cheer. I write to remember him, and to share some observations about what it meant to me to have known him.

I first met Judge Cooke in the Spring of 1981. I was 22 years old, and just completing my second year at Fordham Law School. He was Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeals and had invited me to interview for a clerkship position that would begin following my graduation.

The interview was conducted in his home chambers at the Sullivan County Courthouse, in Monticello, New York, about 100 miles north and west of New York City. Each of the seven judges of the Court of Appeals maintain chambers in their hometowns. The judges would converge on Albany for two-week sessions, to confer and hear argument. During the three weeks in-between sessions, and over the summer, they would return to home chambers to work on writings and ready themselves for the next session, and so forth.

Monticello is situated in the heart of the Catskills, a well-lived-in resort town, home to once-great “borscht belt” hotels — the Concord and Grossingers first among them. (The neighboring town is Liberty, leading some to say, “Give me Liberty or give me Monticello.”)

Judge Cooke was born in Monticello on October 15, 1914. His mother, Mary Elizabeth Pond Cooke, was from a prominent New England family, a graduate of Mount Holyoke College, and a teacher of Latin and mathematics. His father, George Cooke, was a Sullivan County native, a schoolteacher who went on to law school and to become District Attorney of Sullivan County, and later Sullivan County Judge. The village elementary school is named the George Cooke School.

Judge Cooke revered his parents, and spoke of them often.

After graduating from Georgetown and the Albany Law School, the Judge Cooke I knew also was elected Sullivan County Judge. He went on to win election to the state Supreme Court, the state trial court of general jurisdiction.

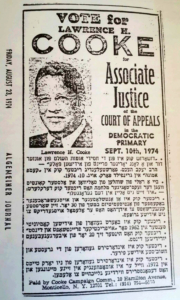

In 1968, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, appointed Judge Cooke, a liberal Democrat, to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, the state’s intermediate appellate court. In 1974, Judge Cooke was elected to the New York Court of Appeals.

In 1968, Gov. Nelson Rockefeller, a Republican, appointed Judge Cooke, a liberal Democrat, to the Appellate Division of the Supreme Court, the state’s intermediate appellate court. In 1974, Judge Cooke was elected to the New York Court of Appeals.

He ran a statewide campaign on $80,000. He shook hands with dairy farmers starting at 5 a.m. He was a lifelong volunteer firefighter, whose comrades introduced him in local communities throughout the state. Orthodox Jews from the Borough of Brooklyn to the bungalow colonies of Sullivan County adored this Catholic Christian man.

Judge Cooke was physically imposing — 6 foot 2, built like a man who enjoyed a hearty breakfast (he did). He had a thick head of red hair (mostly, but not entirely, gray by the time I met him), a big smile, a big warm voice, a big handshake, a big beautiful family, drove a big Olds 98 (the comfortable car for a big man intent on avoiding even a hint of ostentation). He enjoyed practical humor, the kind that doesn’t embarrass or hurt feelings. The more elaborate the better.

He always wore a coat and tie, and well-shined shoes, and a fine Stetson fedora. He would dress even going to the Quickway Diner, one of his regular places, on a Saturday morning.

Judge Cooke was the first person appointed chief judge of the New York Court of Appeals under state constitutional amendments that vested broad administrative power over the court system in the chief judge.

He had been junior member of the court at the time of his appointment by Gov. Hugh Carey in 1979. When he became chief judge, he ended the court’s practice of dining at the men-only University Club in Albany. He resigned from the club when it refused to open its membership. He issued an order forbidding the conduct of judicial business at any discriminatory club.

He assigned judges from less busy rural districts to New York City, where they worked to reduce years’-long backlogs. He could not stand the idea that people being called to appear in court or for jury duty would be kept waiting because of bureaucratic convenience or indifference. “The courts belong to the people,” he would say. He imposed a uniform 9 a.m. starting time for courts, statewide, and had administrative judges canvass the courtrooms to ensure they were in session by the appointed hour.

Judge Cooke had few peers when it came to personal work ethic. He arrived in chambers at 5:30 a.m., and while the court was in session in Albany, typically he would not leave for the day until 10 p.m. He would occupy his early hours in Albany or home chambers with personal correspondence. He would write dozens of post cards each day, always using his own postage.

One employee of the court, who had spent several months convalescing after a serious automobile accident, told us how she had received a card from Judge Cooke every day, some days two. She was not alone.

It was thrilling to be a young lawyer working for Judge Cooke.

Judge Cooke was a fierce champion of press freedoms and consumer rights. He was a pioneer in using the state constitution to protect the rights of the accused. He saw the law as a sacred instrument for advancing equality and fairness, and broadly correcting injustice. He would actively and astutely and cheerfully engage his colleagues to persuade them and win votes for his position in cases, more than once swaying a majority of members who initially had voted against the disposition he proposed.

He considered the written expression of an idea the ultimate crucible of its worthiness. “Let’s see if it writes,” he would say.

What I remember most about being associated with Judge Cooke, lessons as keen today as they were thirty years ago, was how he carried himself in public life.

“Always take the high road,” was advice he received from his father — simple, handy, incisive counsel. Most of us, when faced with a dilemma, know which route is the high road, and that the high road is the preferred course. Self-reminder serves a good purpose.

He offered this collateral concept: “Never give them anything to hang their hat on”.

By this he expressed caution about the importance of appearances — how ambiguity in one’s actions, even when innocently created through lack of attention to detail, may be exploited by people not rooting for your success.

“Every favor creates an obligation,” he also would say — another caution about the perils of reciprocal obligation implied in accepting a gift or favor.

Judge Cooke didn’t advance these aphorisms in a tone of prudish moralism. To the contrary, they would be brightly dispensed as matter of fact, offered under the constructive category of “do yourself a favor.”

They were set against the powerful example of his unfailing thoughtfulness and courtesy toward others. Judge Cooke, above all else, demonstrated that one can rise to the top of a highly competitive profession, a profession that by its nature involves adversarial process, and — without exception — treat people with respect.

Unlike so many who have ostensibly achieved “prominence,” Judge Cooke never was abrupt, never would embarrass, never would be high-handed, always would search for a way for others to save face, even when he had to be unyielding in contentious circumstances.

He considered such courtesy to be an essential condition — the sine qua non — of true achievement. The closing paragraphs of his obituary in the New York Times capture this defining aspect of his character:

“Judge Cooke agreed that his country-style informality and small-town involvement, which included four decades of service as a volunteer firefighter in Monticello and later in administrative firefighting posts throughout Sullivan County, led some people to regard him as something of a hayseed. But his critics, he said, underestimated him…

”’I went to the proper schools. I had been around, and I felt I could hold my own in any company. But I never lorded over anybody. I felt you could be efficient and still be nice.’”

*

I was the second to last clerk Judge Cooke hired. Jeanne Philips-Roth was his last clerk.

New York’s constitution imposes mandatory retirement at the end of the year in which a judge turns 70, or at least it did back in our clerking days.

Judge Cooke turned 70 in 1984, and retired at the end of the year. Jeanne and I were kept on an extra month to help him, as he put it, “break camp.”

He told us something during that time that had not occurred to me but proved to be true. He would say, “when you’re dead, you’re dead.” By that he meant that in retirement his professional prominence would greatly decrease.

He offered this not as a lament but as a healthy perspective. He always had understood that the professional attentiveness of others, the laughing at his jokes, had less to do with him than the office he held.

But he remained active in private practice and in teaching and retained broad respect in the profession and had an immense and deep following in ordinary people with whom he came in contact in daily life — literally thousands of people whose names, and the names of their children, and the names of their grandchildren, and the schools where their children and grandchildren attended, and remembrances of their parents and grandparents, he had a superhuman capacity to commit to memory and to summon immediately.

I remember one card wishing him well on retirement arrived by mail after having been posted with just a photograph of him in place of a mailing address.

Jeanne and I stayed in regular touch with him, and would have dinner with him when he was in New York City. After we were married, we would bring the girls with us to visit the Judge and Mrs. Cooke in Monticello.

Their white frame house on the outskirts of Monticello’s downtown was famous for its splendid gardens — flower and vegetable.

Alice, our youngest, was named with Mrs. Cooke very much in mind — Alice McCormack Cooke, whose personal qualities were as great and memorable as Judge Cooke’s.

In rummaging through files looking for things to jog my recollections, I came across the program for a luncheon Judge Cooke’s law clerks held for him when he turned 80 in in 1994 — six years before his death.

The main part of the program was given over to good wishes and remembrances, republished in letter form from prominent people and his secretaries and the clerks themselves. At the very end is a letter dated November 3, 1966 from a Gladys Cryer of Purling, New York.

Ms. Cryer, it appears, had recently served on a jury in a case over which Judge Cooke had presided at the Catskill Court House. She wrote:

I enjoyed serving on the jury which incidentally was my first experience, although I hope not my last, and I tried hard to do my duty as I saw it.

Thank you for being so nice through it all!

She offered this postscript:

“P.S. I hope you have real good luck with your tulips.”

It says something about Judge Cooke that’s worth remembering that Ms. Cryer would write such a letter — and that he would keep it.

*