Description

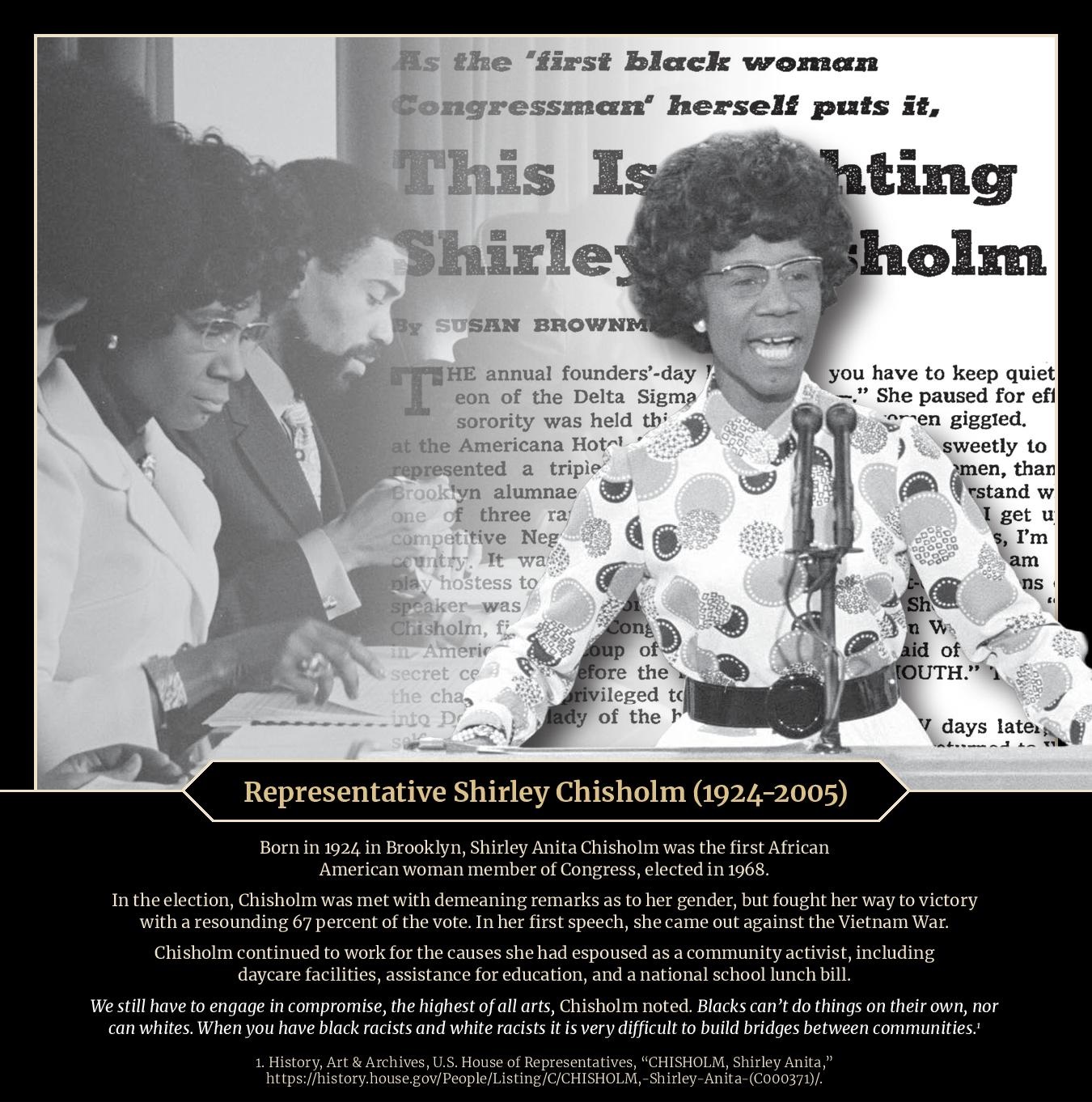

Born in 1924 in Brooklyn, Shirley Anita Chisholm was the first African American woman member of Congress, elected in 1968.

In the election, Chisholm was met with demeaning remarks as to her gender, but fought her way to victory with a resounding 67 percent of the vote. In her first speech, she came out against the Vietnam War.

Chisholm continued to work for the causes she had espoused as a community activist, including daycare facilities, assistance for education, and a national school lunch bill.

We still have to engage in compromise, the highest of all arts, Chisholm noted. Blacks can’t do things on their own, nor can whites. When you have black racists and white racists it is very difficult to build bridges between communities.[1]

[1] History, Art & Archives, U.S. House of Representatives, “CHISHOLM, Shirley Anita,” https://history.house.gov/People/Listing/C/CHISHOLM,-Shirley-Anita-(C000371)/.

Images:

The New York Times, April 13, 1969. Copyright the New York Times.

A hearing of the Congressional Black Caucus, 1971. From Left to Right: Hon. Shirley Chisholm, Rep. William L. Clay, Rep. Charles C. Diggs, Jr., Rep. Parren J. Mitchell, Rep. Walter Fauntroy, and Rep. Louis Stokes. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection, LC-U9-24471-17A.

Rep. Shirley Chisholm thanks delegates that the Democratic National Convention, 1972. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, U.S. News & World Report Magazine Collection, LC-U9-26274-20.

February 2022

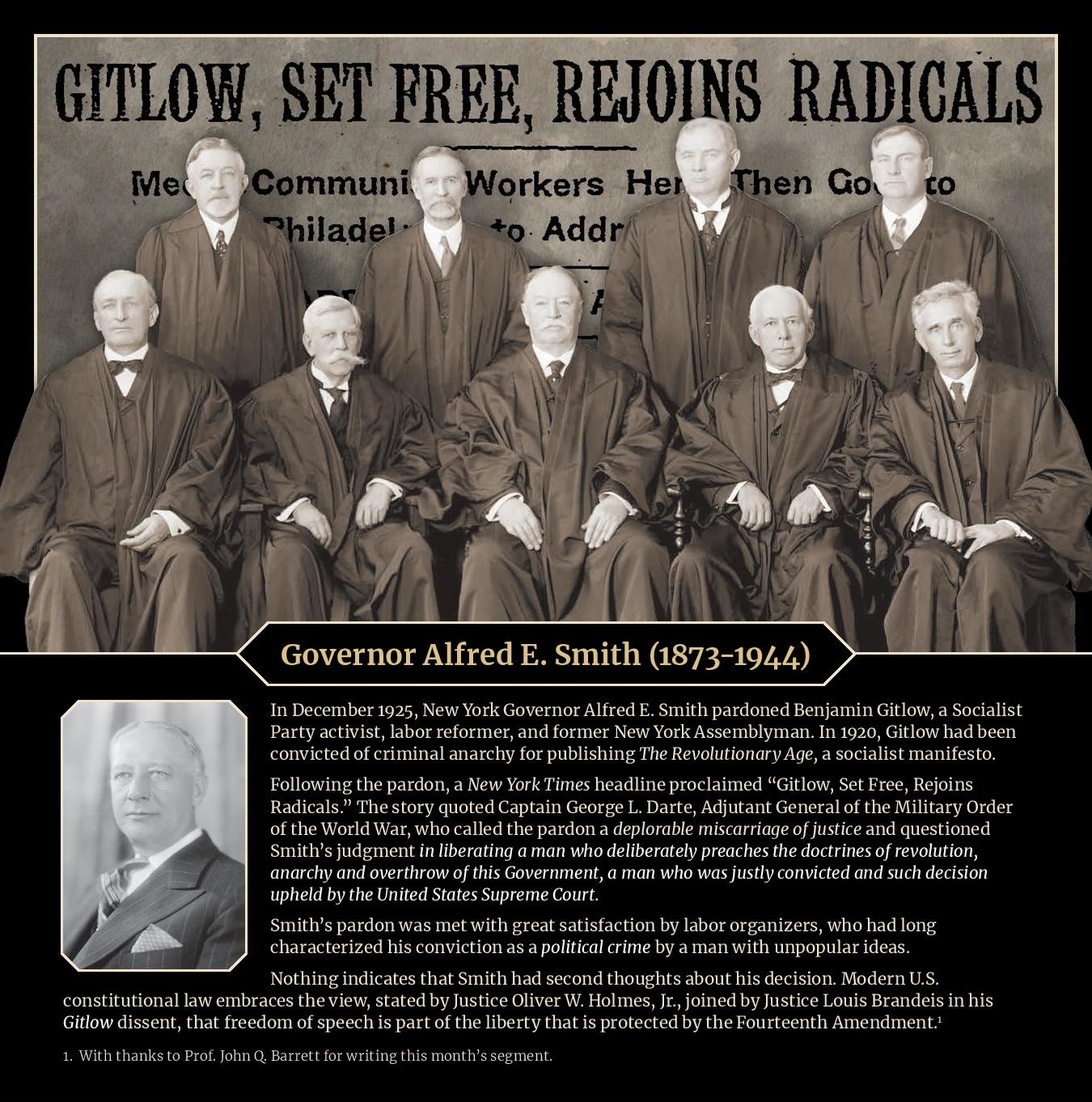

In December 1925, New York Governor Alfred E. Smith pardoned Benjamin Gitlow, a Socialist Party activist, labor reformer, and former New York Assemblyman. In 1920, Gitlow had been convicted of criminal anarchy for publishing The Revolutionary Age, a socialist manifesto.

Following the pardon, a New York Times headline proclaimed “Gitlow, Set Free, Rejoins Radicals.” The story quoted Captain George L. Darte, Adjutant General of the Military Order of the World War, who called the pardon a deplorable miscarriage of justice and questioned Smith’s judgment in liberating a man who deliberately preaches the doctrines of revolution, anarchy and overthrow of this Government, a man who was justly convicted and such decision upheld by the United States Supreme Court.

Smith’s pardon was met with great satisfaction by labor organizers, who had long characterized his conviction as a political crime by a man with unpopular ideas.

Nothing indicates that Smith had second thoughts about his decision. Modern U.S. constitutional law embraces the view, stated by Justice Oliver W. Holmes, Jr., joined by Justice Louis Brandeis in his Gitlow dissent, that freedom of speech is part of the liberty that is protected by the Fourteenth Amendment.[1]

[1] With thanks to Prof. John Q. Barrett for writing this month’s segment.

Images:

The Supreme Court of the United States at the time of the Gitlow trial. Left to right, front row: Hon. James Clark McReynolds, Hon. Oliver Wendell Holmes, Jr., Chief Justice William Howard Taft, Hon. Willis Van Devanter, Hon. Louis D. Brandeis. Back row: Hon. Edward Terry Sanford, Hon. George A. Sutherland, Hon. Pierce Butler, Hon. Harlan Fiske Stone. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H25-86410-BL.

The New York Times, December 13, 1925. Copyright the New York Times.

Portrait of Governor Alfred E. Smith, c. 1925. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H25-131027-BA.

March 2022

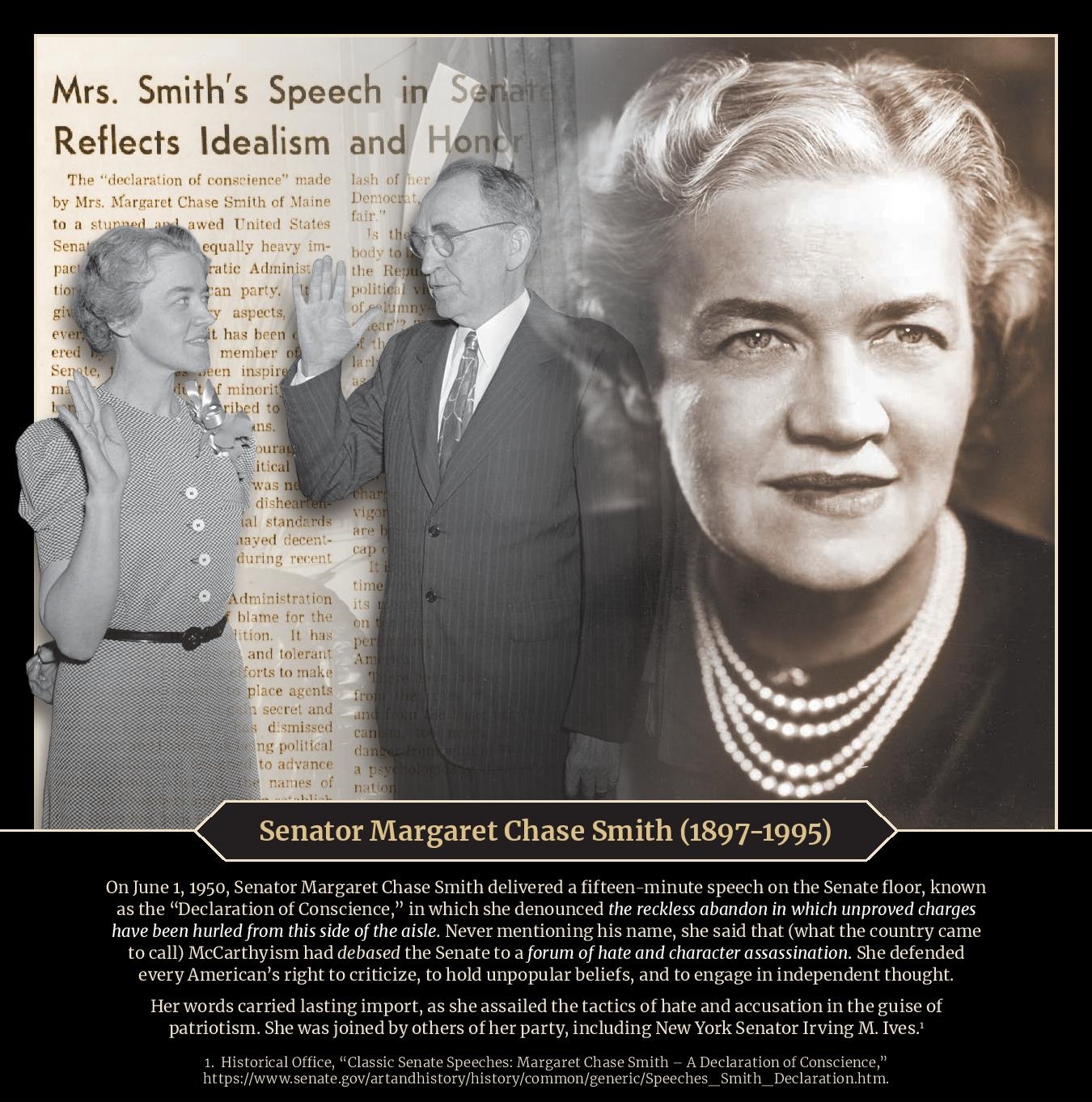

On June 1, 1950, Senator Margaret Chase Smith delivered a fifteen-minute speech on the Senate floor, known as the “Declaration of Conscience,” in which she denounced the reckless abandon in which unproved charges have been hurled from this side of the aisle. Never mentioning his name, she said that (what the country came to call) McCarthyism had debased the Senate to a forum of hate and character assassination. She defended every American’s right to criticize, to hold unpopular beliefs, and to engage in independent thought.

Her words carried lasting import, as she assailed the tactics of hate and accusation in the guise of patriotism. She was joined by others of her party, including New York Senator Irving M. Ives.[1]

[1] Senate Historical Office, “Classic Senate Speeches: Margaret Chase Smith – A Declaration of Conscience,” https://www.senate.gov/artandhistory/history/common/generic/Speeches_Smith_Declaration.htm.

Images:

Portrait of Senator Margaret Chase Smith, Republican from Maine, who served from 1949 to 1973. Image courtesy of the U.S. Senate Historical Office.

Margaret Chase Smith as she is sworn into the House of Representatives, filling the vacancy left by her late husband, 1940. She later became a senator. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-DIG-hec-28784.

The Brooklyn Daily Eagle, June 4, 1950. Courtesy of Brooklyn Public Library’s Brooklyn Newsstand.

April 2022

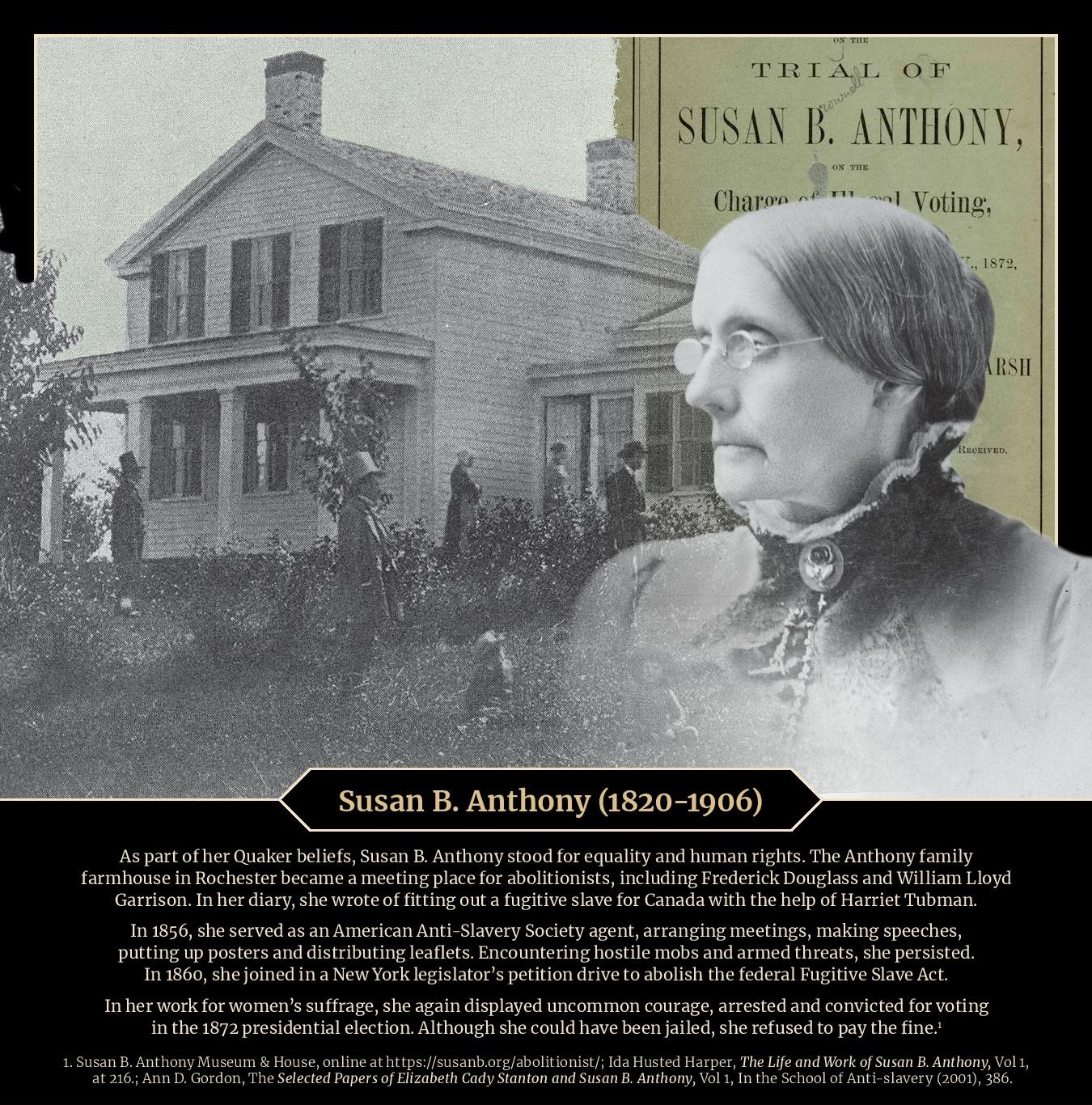

As part of her Quaker beliefs, Susan B. Anthony stood for equality and human rights. The Anthony family farmhouse in Rochester became a meeting place for abolitionists, including Frederick Douglass and William Lloyd Garrison. In her diary, she wrote of fitting out a fugitive slave for Canada with the help of Harriet Tubman.

In 1856, she served as an American Anti-Slavery Society agent, arranging meetings, making speeches, putting up posters and distributing leaflets. Encountering hostile mobs and armed threats, she persisted. In 1860, she joined in a New York legislator’s petition drive to abolish the federal Fugitive Slave Act.

In her work for women’s suffrage, she again displayed uncommon courage, arrested and convicted for voting in the 1872 presidential election. Although she could have been jailed, she refused to pay the fine.[1]

[1] Susan B. Anthony Museum & House, online at https://susanb.org/abolitionist/; Ida Husted Harper, The Life and Work of Susan B. Anthony, Vol 1, at 216.; Ann D. Gordon, The Selected Papers of Elizabeth Cady Stanton and Susan B. Anthony, Vol 1, In the School of Anti-slavery (2001), 386.

Images:

Susan B. Anthony’s family farm, near Rochester, c. 1855. From the collection of the Rochester Public Library Local History & Genealogy Division.

Cover of An Account of the Proceedings on the Trial of Susan B. Anthony, 1874. The New York Public Library, General Research Division.

Portrait of Susan B. Anthony, c. 1875. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-B2-5136-6.

May 2022

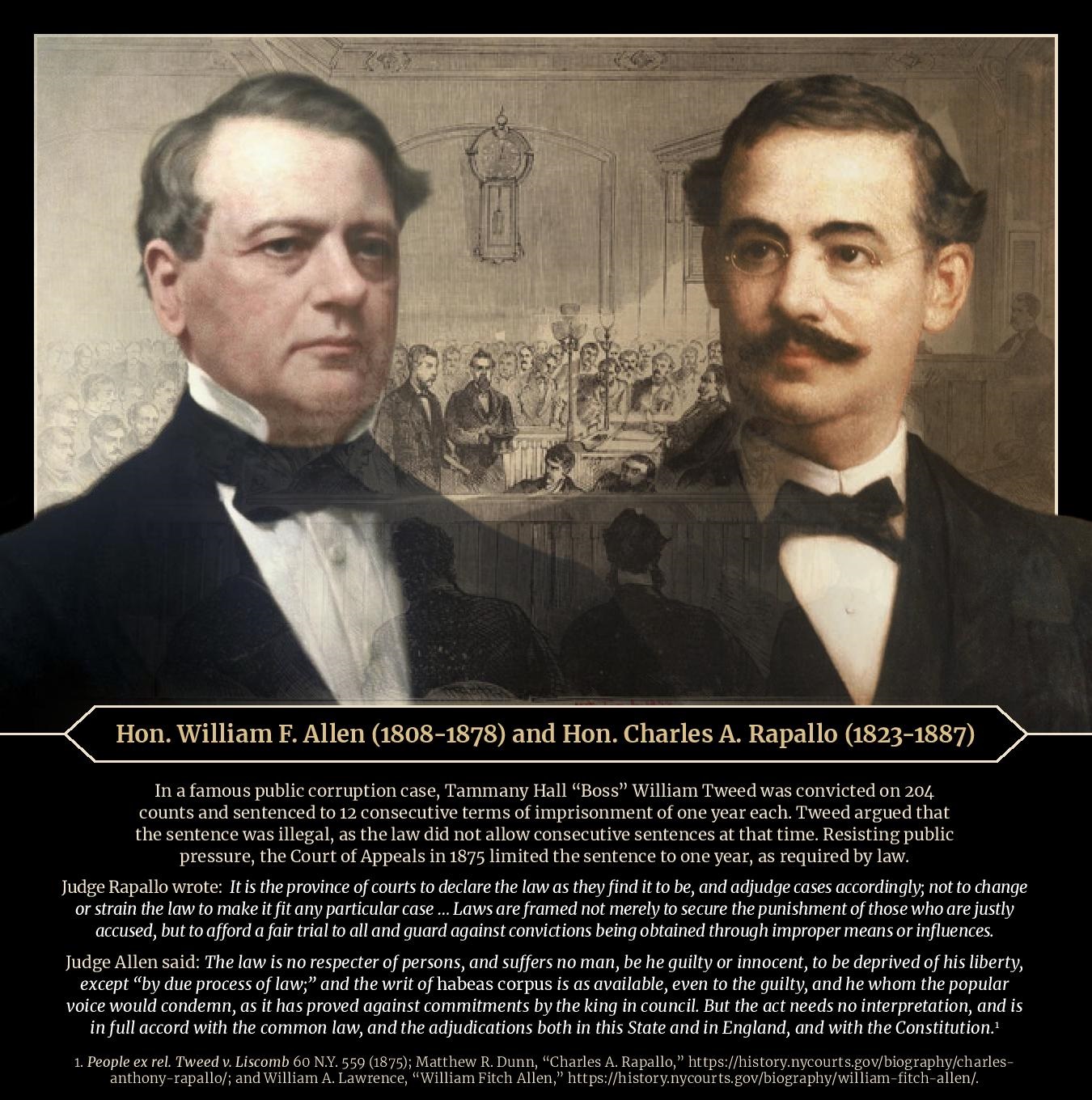

In a famous public corruption case, Tammany Hall “Boss” William Tweed was convicted on 204 counts and sentenced to 12 consecutive terms of imprisonment of one year each. Tweed argued that the sentence was illegal, as the law did not allow consecutive sentences at that time.

Resisting public pressure, the Court of Appeals in 1875 limited the sentence to one year, as required by law. Judge Rapallo wrote:

It is the province of courts to declare the law as they find it to be, and adjudge cases accordingly; not to change or strain the law to make it fit any particular case . . . Laws are framed not merely to secure the punishment of those who are justly accused, but to afford a fair trial to all and guard against convictions being obtained through improper means or influences.

Judge Allen said:

The law is no respecter of persons, and suffers no man, be he guilty or innocent, to be deprived of his liberty, except “by due process of law;” and the writ of habeas corpus is as available, even to the guilty, and he whom the popular voice would condemn, as it has proved against commitments by the king in council. But the act needs no interpretation, and is in full accord with the common law, and the adjudications both in this State and in England, and with the Constitution.[1]

[1] People ex rel. Tweed v. Liscomb 60 N.Y. 559 (1875); Matthew R. Dunn, “Charles A. Rapallo,” https://history.nycourts.gov/biography/charles-anthony-rapallo/; and William A. Lawrence, “William Fitch Allen,” https://history.nycourts.gov/biography/william-fitch-allen/

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Charles A. Rapallo. From the collection of the New York Court of Appeals.

Portrait of Hon. William Fitch Allen. From the collection of the New York Court of Appeals.

William M. Tweed’s arraignment in the Court of General Sessions, 1872. The case was appealed to the New York Court of Appeals. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Picture Collection.

June 2022

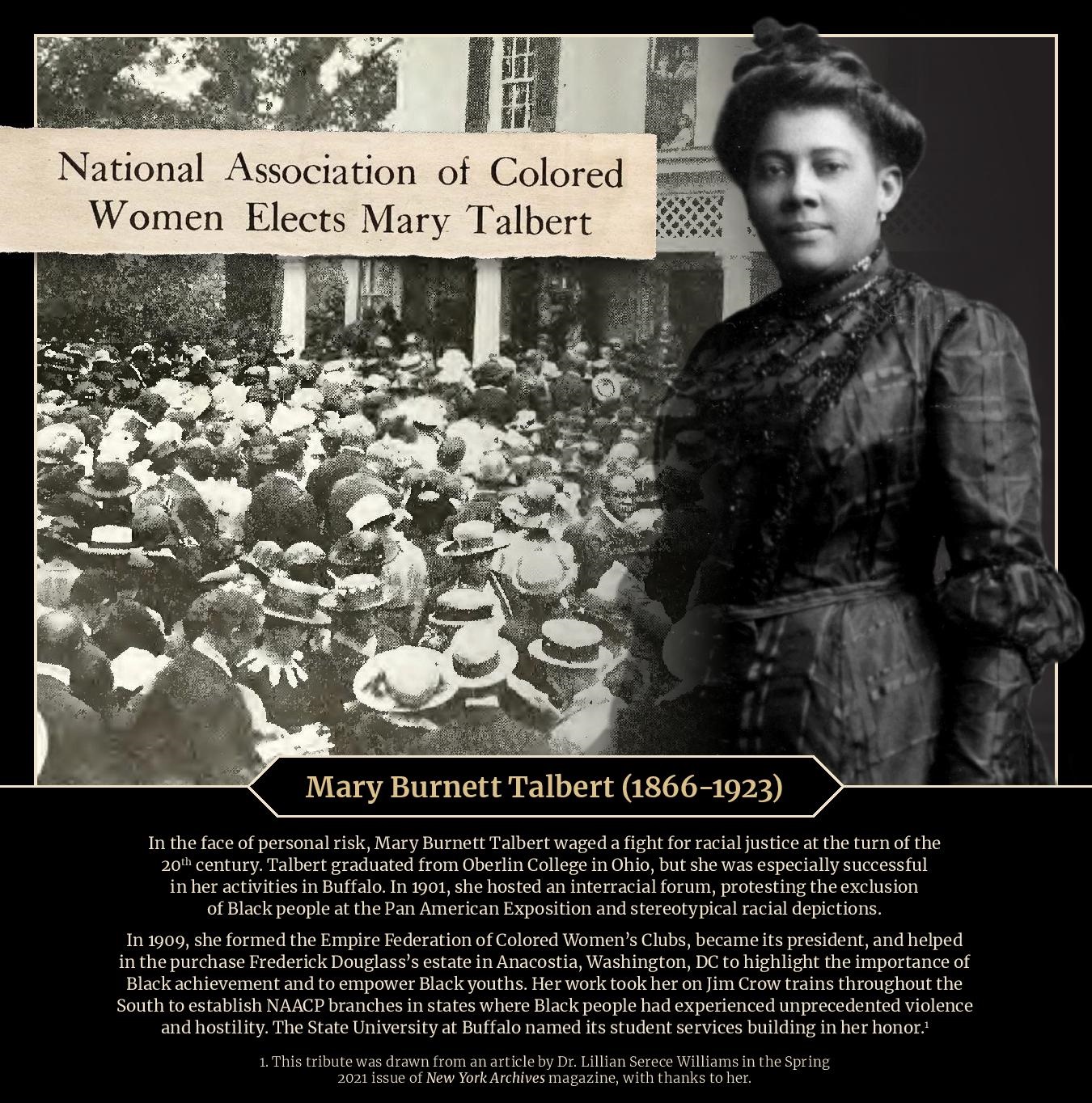

In the face of personal risk, Mary Burnett Talbert waged a fight for racial justice at the turn of the 20th century.

Talbert graduated from Oberlin College in Ohio, but she was especially successful in her activities in Buffalo. In 1901, she hosted an interracial forum, protesting the exclusion of Black people at the Pan American Exposition and stereotypical racial depictions.

In 1909, she formed the Empire Federation of Colored Women’s Clubs, became its president, and helped in the purchase Frederick Douglass’s estate in Anacostia, Washington, DC to highlight the importance of Black achievement and to empower Black youths.

Her work took her on Jim Crow trains throughout the South to establish NAACP branches in states where Black people had experienced unprecedented violence and hostility.

The State University at Buffalo named its student services building in her honor.[1]

[1] This tribute was drawn from an article by Dr. Lillian Serece Williams in the Spring 2021 issue of New York Archives magazine, with thanks to her.

Images:

Portrait of Mary Burnett Talbert. Published in Twentieth Century Nego Literature: A Cyclopeida of Thought on the Vital Topics Relating to the American Nego, edited by Dr. D.W. Culp, 1902.

Article announcing the election of Mary Talbert as President of the National Association of Colored Women. Published in The Champion Magazine, 1916.

The National Association of Colored Women hosts a dedication ceremony at the home of Frederick Douglass, due to efforts lead by Mary Burnett Talbert. Published in The Crisis, 1922.

July 2022

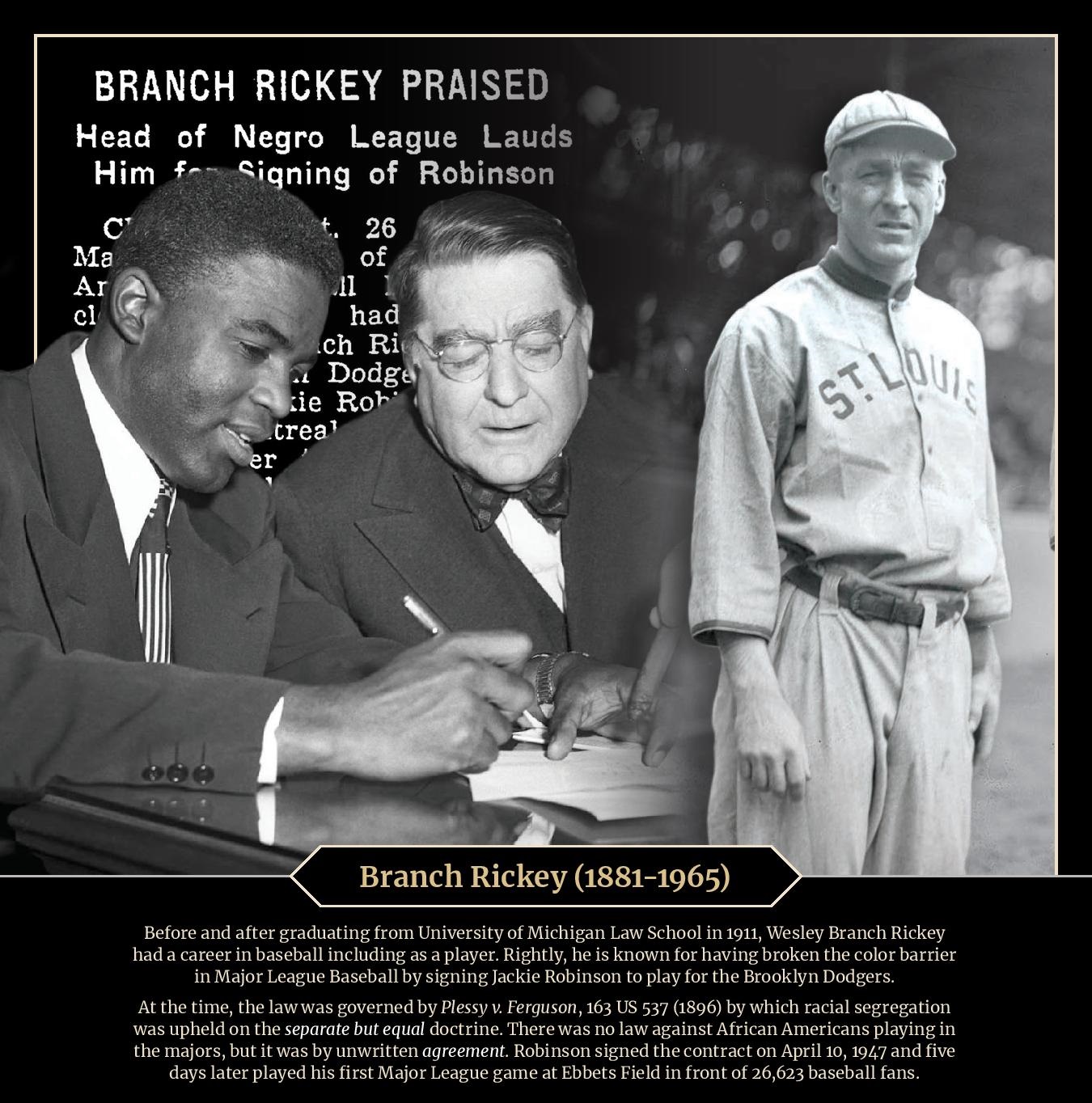

Before and after graduating from University of Michigan Law School in 1911, Wesley Branch Rickey had a career in baseball including as a player. Rightly, he is known for having broken the color barrier in Major League Baseball by signing Jackie Robinson to play for the Brooklyn Dodgers.

At the time, the law was governed by Plessy v. Ferguson, 163 US 537 (1896) by which racial segregation was upheld on the separate but equal doctrine. There was no law against African Americans playing in the majors, but it was by unwritten agreement. Robinson signed the contract on April 10, 1947 and five days later played his first Major League game at Ebbets Field in front of 26,623 baseball fans.

Images:

Jackie Robinson signs a minor league contract with Branch Rickey, 1945. Robinson would make his Major League debut with the Brooklyn Dodgers two years later. Courtesy of Sports Illustrated Vault.

Branch Rickey as a Major League Baseball player for the St. Louis Browns, c. 1914. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-F81-1264.

The New York Times, October 27. 1945. Copyright The New York Times.

August 2022

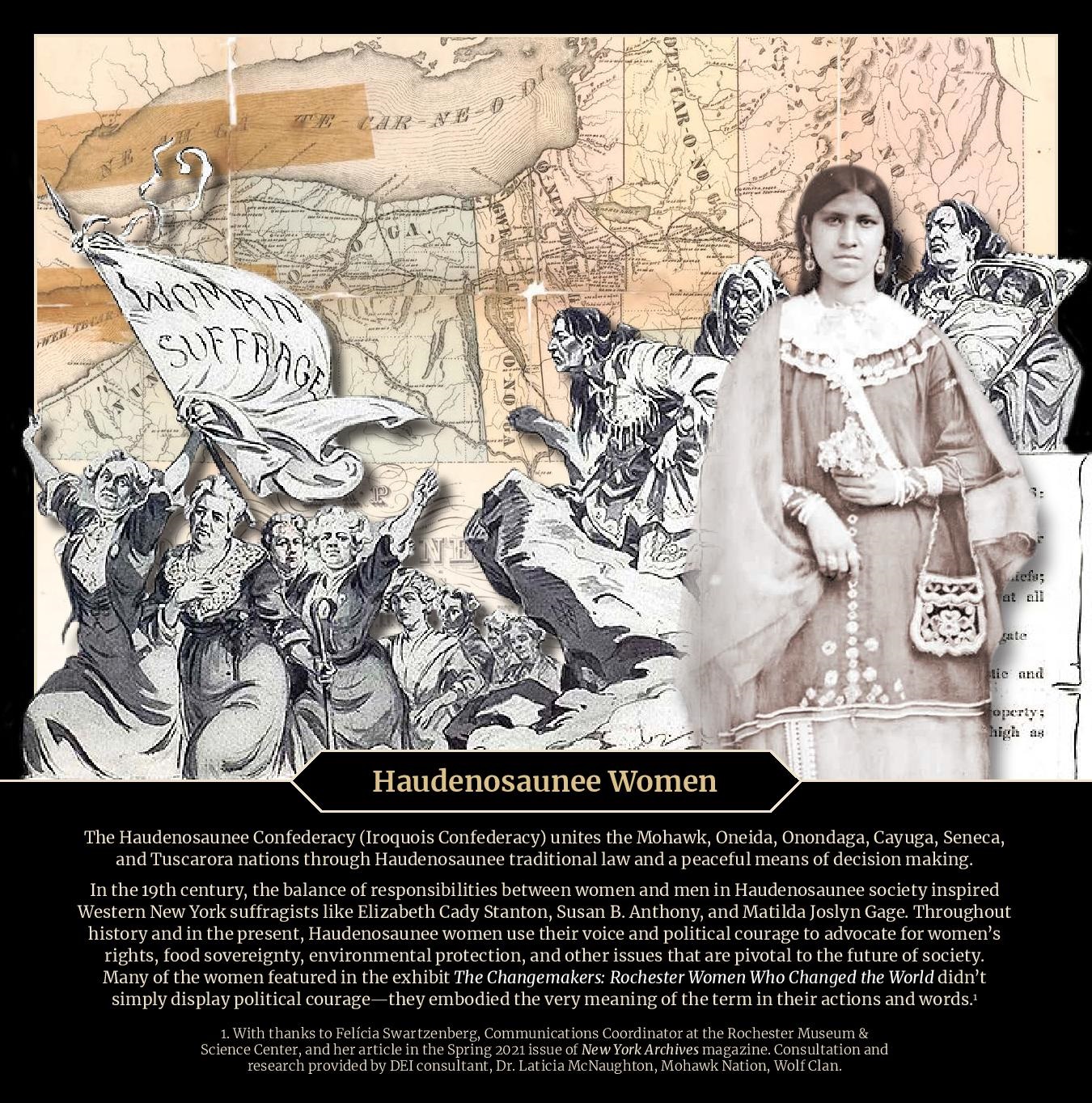

The Haudenosaunee Confederacy (Iroquois Confederacy) unites the Mohawk, Oneida, Onondaga, Cayuga, Seneca, and Tuscarora nations through Haudenosaunee traditional law and a peaceful means of decision making.

In the 19th century, the balance of responsibilities between women and men in Haudenosaunee society inspired Western New York suffragists like Elizabeth Cady Stanton, Susan B. Anthony, and Matilda Joslyn Gage. Throughout history and in the present, Haudenosaunee women use their voice and political courage to advocate for women’s rights, food sovereignty, environmental protection, and other issues that are pivotal to the future of society. Many of the women featured in the exhibit The Changemakers: Rochester Women Who Changed the World didn’t simply display political courage—they embodied the very meaning of the term in their actions and words.[1]

[1] With thanks to Felícia Swartzenberg, Communications Coordinator at the Rochester Museum & Science Center, and her article in the Spring 2021 issue of New York Archives magazine. Consultation and research provided by DEI consultant, Dr. Laticia McNaughton, Mohawk Nation, Wolf Clan.

Images:

Map of Ho-De-No-Sau-Nee-Ga, or the territories of the Haudenosaunee people, 1720. Library of Congress, Geography & Map Division, G3801.E1 1720 .M6.

Peace Queen, oil painting, Ernest Smith, Tonawanda Reservation, 1936. From the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, N.Y.

Daguerreotype of Caroline Parker, c. 1849. Courtesy of the Rochester Museum & Science Center, Rochester, N.Y.

September 2022

In 1860, the New York Legislature considered a measure to grant freedom and official protection to any slave, even a fugitive, who set foot on New York soil. A Brooklyn Assemblyman criticized the measure as being a violation of federal law and also denounced the proposal in vehement racist terms. New York’s Delaware County Assemblyman Barna R. Johnson answered:

Are we to be compelled by law to aid the master to catch his slave, and help him with his human chattel, on to the land of chains, and stripes, and slavery hopeless, cruel, unmitigated slavery? Is it fair for a quarter of a million of slaveholders to rule with a rod of iron, not only the four millions of slaves, and the free people of color, and the five millions of Southern whites, who would rejoice in the abolition of slavery, but the twenty-millions of free people at the North also?

Images:

The New York Times, November 14, 1860. Copyright the New York Times.

Practical Illustration of the Fugitive Slave Law, satirizing the tension between abolitionists and enforcers of the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, 1851. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-DIG-ppmsca-34495.

Portrait of Barna R. Johnson, c. 1860. Courtesy of the author.

October 2022

In a slavery rendition case in 1852, Horace Preston was arrested as a claimed runaway. The U.S. Commissioner issued a warrant of arrest and cynically dispatched Preston south as his wife and four-year-old child looked on, sobbing. Defending him, Erastus D. Culver and John Jay II had no recourse under law but would not let the matter pass without telling the public about the sham proceeding.

How far [his conduct] in admitting all evidence offered for the claimant, of whatever character, including an affidavit made without knowledge, and confessions of the defendant while in duress—his refusal to compel an interested witness to answer on a cross-examination, and his cutting off all opportunity of rebutting evidence by a snap judgment, made in violation of good faith—comports with that strict impartiality and fairness which ought to be preserved in trials involving the right to liberty is a question which the undersigned submit to the judgment of the American people.[1]

[1] New York Tribune, April 5, 1852, 4. After being sent South, Horace Preston was bought back for $1200 and came home. See Samuel May, The Fugitive Slave Law and Its Victims (New York: American Anti-Slavery Society, 1861), 22.

Images:

Portrait of Erastus D. Culver, undated. Courtesy of the owner Henry D. Ryder, great-great grandson.

Photograph of John Jay, II. Massachusetts Historical Society, Portraits of American Abolitionists, Photo 81.372.

New York Tribune, April 5, 1852.

A Black woman pleads with an officer at a city prison in New York, 1835. Originally published in The Anti-Slavery Record by R.G. Williams for the American Anti-Slavery Society, 1835.

November 2022

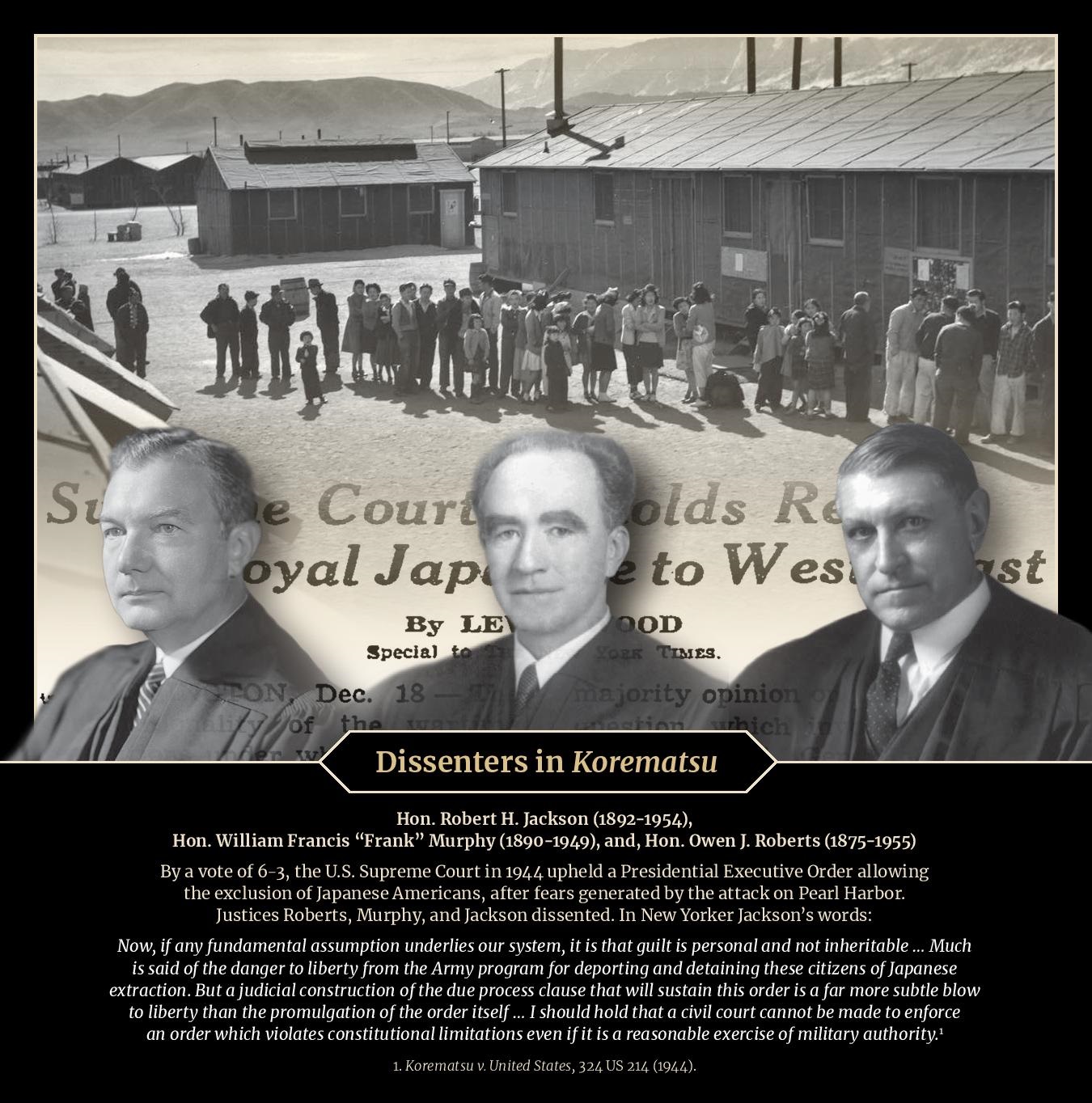

By a vote of 6-3, the U.S. Supreme Court in 1944 upheld a Presidential Executive Order allowing the exclusion of Japanese Americans, after fears generated by the attack on Pearl Harbor. Justices Roberts, Murphy, and Jackson dissented. In New Yorker Jackson’s words:

Now, if any fundamental assumption underlies our system, it is that guilt is personal and not inheritable … Much is said of the danger to liberty from the Army program for deporting and detaining these citizens of Japanese extraction. But a judicial construction of the due process clause that will sustain this order is a far more subtle blow to liberty than the promulgation of the order itself … I should hold that a civil court cannot be made to enforce an order which violates constitutional limitations even if it is a reasonable exercise of military authority.[1]

[1] Korematsu v. United States, 324 US 214 (1944).

Images:

Portrait of Hon. Owen J. Roberts, c. 1936. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, LC-USZ62-64397.

Portrait of Hon. Robert H. Jackson, c. 1940. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H25-184905-GK.

Portrait of Hon. Frank Murphy, c. 1940. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-USZ62-47787.

The line for lunch at the Manzanar Relocation Center in California, 1943. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, Ansel Adams, photographer, LC-DIG-ppprs-00368.

The New York Times, December 19, 1944. Copyright the New York Times.

December 2022

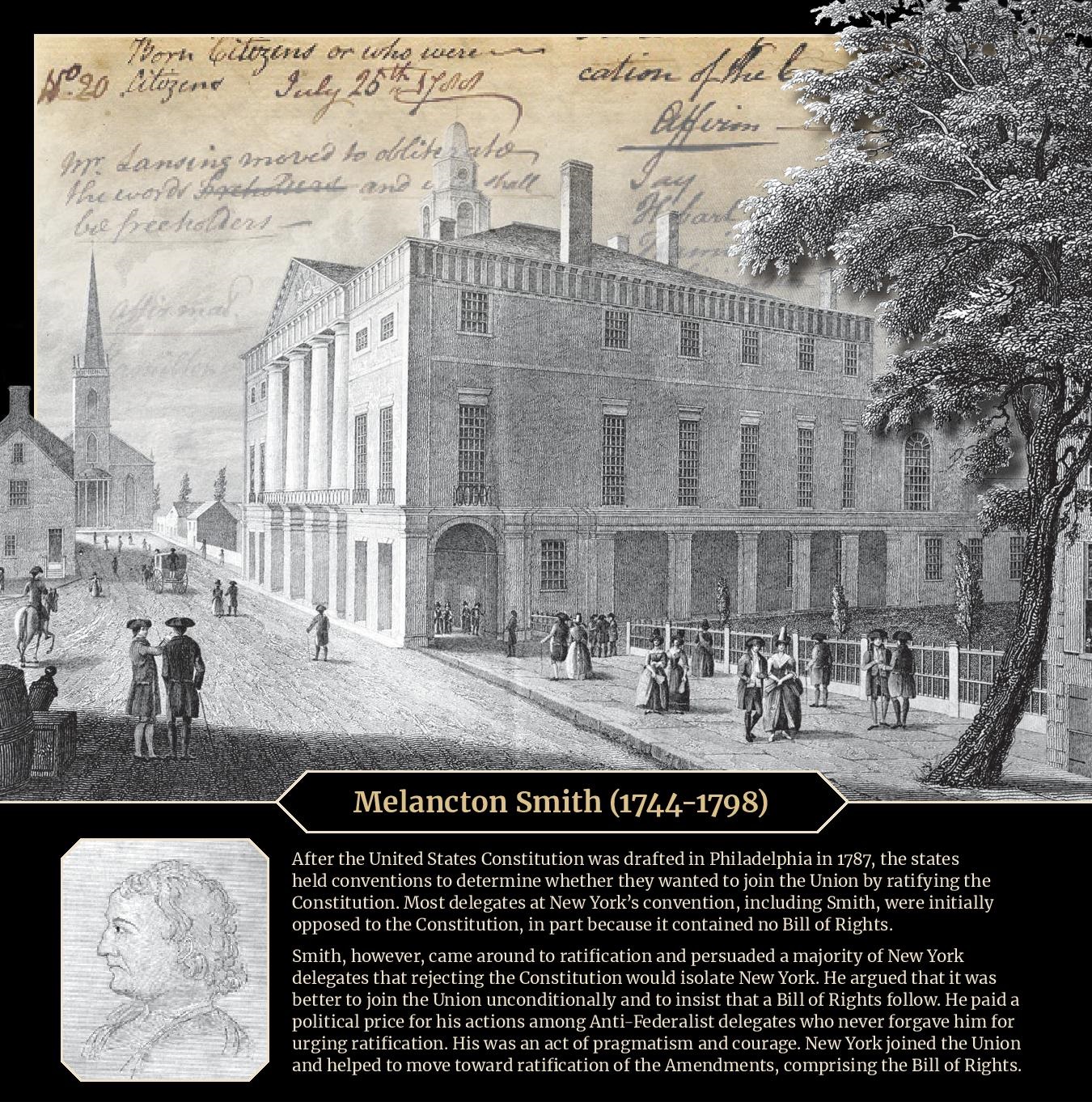

After the United States Constitution was drafted in Philadelphia in 1787, the states held conventions to determine whether they wanted to join the Union by ratifying the Constitution. Most delegates at New York’s convention, including Smith, were initially opposed to the Constitution, in part because it contained no Bill of Rights.

Smith, however, came around to ratification and persuaded a majority of New York delegates that rejecting the Constitution would isolate New York. He argued that it was better to join the Union unconditionally and to insist that a Bill of Rights follow. He paid a political price for his actions among Anti-Federalist delegates who never forgave him for urging ratification. His was an act of pragmatism and courage. New York joined the Union and helped moved toward ratification of the Amendments, comprising the Bill of Rights.

Images:

Portrait of Melancton Smith, undated. The New York Public Library, The Miriam and Ira D. Wallach Division of Art, Prints and Photographs: Print Collection.

Votes for New York’s ratification of the U.S. Constitution, 1788. Collection of the New-York Historical Society.

The Old City Hall on Wall Street, NYC, where George Washington took the oath of office after ratification of the U.S. Constitution. Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division, photograph by Harris & Ewing, LC-H22-D-5928.