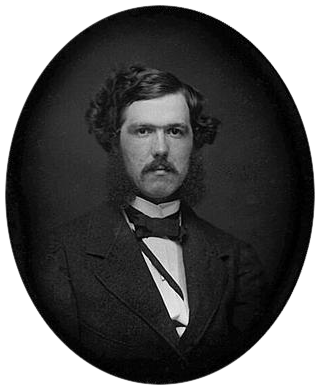

1829-1886

Chester Alan Arthur was born in the town of Fairfield, Franklin County, Vermont, on October 5, 1829. The family remained in Fairfield until 1832, and then lived in several other locations in Vermont for a time before moving to Lansingburgh, New York, where Arthur’s abolitionist father, the Rev. William Arthur, preached in the Baptist church. Chester Arthur was educated at the Lansingburgh Academy and in the Lyceum, a preparatory school for Union College. Arthur graduated from Union College in Schenectady in 1849 “with maximum honors” and then commenced his legal studies, first at the State and National Law School in Ballston Spa, New York, and then, in 1853, in the Brooklyn law office of his father’s friend and fellow abolitionist, Erastus D. Culver. When he was admitted to the bar in May 1854, Arthur was invited to join in the partnership, now renamed Culver, Parker & Arthur.

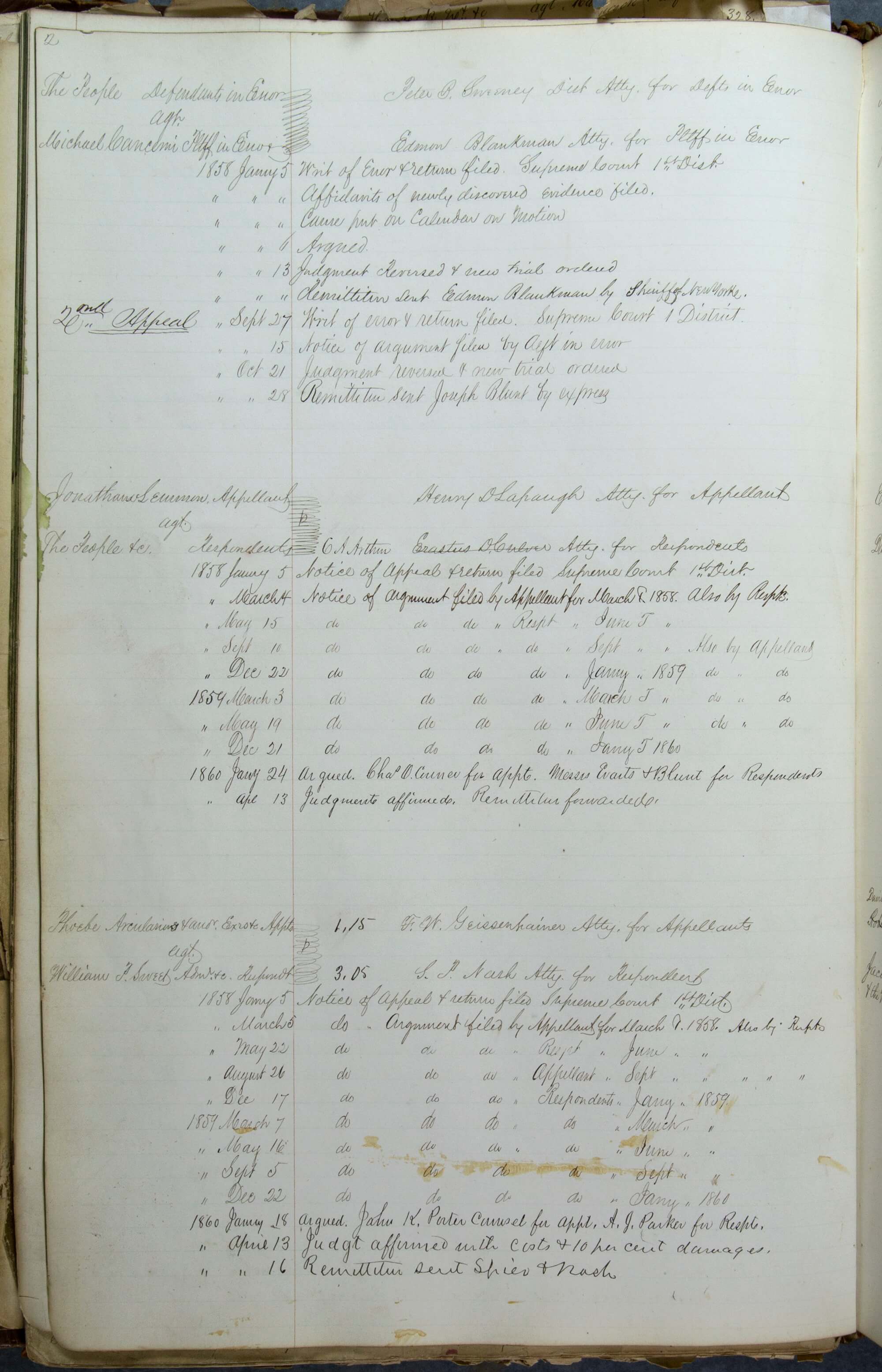

In 1852, Erastus Culver and John Jay, grandson of Chief Justice John Jay, represented the petitioner in the Lemmon Slave Case. Judge Elijah Paine ruled that the Lemmon slaves became free when they landed in New York. Lemmon, with the support of the government of Virginia, appealed the decision to the New York Supreme Court. Governor Myron Clark, in his 1855 Annual Message to the Legislature, noted the need to appoint counsel to represent the interests of New York State in the Lemmon case, and the Legislature responded by passing a joint resolution authorizing the Governor to appoint the Attorney-General and other counsel. Governor Clark appointed Attorney-General Ogden Hoffman, who was supported in the case by Joseph Blunt and the law firm of Culver, Parker and Arthur. When Culver became the Judge of the Brooklyn City Court in 1854, Chester Arthur assumed responsibility for the law practice. Following Hoffman’s death, William Evarts was appointed in his place, and it was he who argued the appeals. The New York Supreme Court and the New York Court of Appeals upheld Judge Paine’s decision, and had it not been for the outbreak of the Civil War, the case would have been appealed by the State of Virginia to the Supreme Court of the United States. The Court of Appeals decided the Lemmon Slave Case in March of 1860 and an appropriations bill enacted into law by the Legislature in July 1860 contained the following provisions:

To William M. Evarts, for argument of the “Lemmon slave case” before the court of appeals; the sum of five hundred dollars.

To Culver, Parker and Arthur, for services in the same case, five hundred dollars; and for taxed costs in supreme court, the sum of two hundred and thirty-nine dollars, and for taxable costs on appeal, the sum of one hundred and fifty-two dollars.

Further on in the same enactment, the following appears:

To Messrs. Roberts, Underhill, Kempston and Warburton, by order of C. A. Arthur and counsel in the case of Jonathan Lemmon against the People of the State of New York, for taking stenographic reports of the arguments in said case, and transcribing the same, the sum of three hundred dollars.

Arthur’s work in support of African American rights is also exemplified by the 1854 case of Jennings v. Third Ave. R.R. Co., where Arthur represented an African American woman ejected from a Third Avenue streetcar reserved for whites. Arthur argued this civil rights case in Brooklyn Circuit Court, and won a verdict in favor of Jennings. As a result, New York’s streetcars were desegregated by 1861.

Like many young men of the time, Chester Arthur was a member of the New York Militia and served as judge-advocate of the Second Brigade. At the beginning of 1861, when war was threatening and the southern states were seceding from the Union, New York Governor Edwin D. Morgan appointed Chester Arthur to his staff as engineer-in-chief with the rank of brigadier-general. He had responsibility for upgrading and protecting New York’s harbor defenses, no small task since the harbor’s numerous fortifications had long been in a state of neglect. The report Arthur submitted in January 1862 indicates his exemplary performance.

Governor Morgan then appointed Arthur assistant quartermaster with responsibility for supplying barracks, food, and equipment for the New York militia. When the war broke out on July 27, 1862, three weeks after President Lincoln’s call for 300,000 more men, Arthur was appointed quartermaster-general and oversaw the construction of a huge tent city in City Hall Park in Lower Manhattan, where thousands of men gathered, were provisioned, and sent to war. In February 1862, the Governor appointed Arthur inspector-general. In this capacity, Arthur inspected the New York troops at Fredericksburg and Chickahominy. He remained in office until the end of 1862, when Horatio Seymour was elected to the governorship of New York and Arthur was replaced by a member of Seymour’s party.

In January 1863, Arthur returned to his law partnership with Henry G. Gardner, and concentrated on cases involving war-related damages and reimbursements. The practice thrived and Arthur became a wealthy man. He remained involved in Republican politics, and on November 20, 1871, President Grant appointed him Collector of the Port of New York, a lucrative position that he held until July 11, 1878.

Chester Arthur was a delegate-at-large to the Republican National Convention in Chicago in June 1880, which nominated James A. Garfield for the office of the President and Arthur for the office of Vice President. The following November, Garfield and Arthur were elected to the offices they had sought, and they were sworn into their respective offices on March 4, 1881. Not long afterward, President Garfield was shot and Vice-President Arthur became President on September 21, 1881. Among Arthur’s notable achievements in office were the enactment of the Pendleton Civil Service Reform Act and his veto of the Chinese Exclusion Act, which forced Congress to reduce its ban from twenty to ten years in order to avoid the failure of an override.

At the end of Arthur’s administration, Mark Twain is quoted as saying: I am but one in 55,000,000; still, in the opinion of this one-fifty-five millionth of the country’s population, it would be hard to better President Arthur’s administration.

By the end of his term, President Arthur was in poor health and did not seek reelection in 1884, but returned to New York where he resumed his law practice. He died, suddenly, on November 18, 1886 at his residence on Lexington Avenue in New York City, and was buried at the Civil War cemetery in Albany, New York.

Sources

Thomas C. Reeves. Gentleman Boss: The Life of Chester Alan Arthur (1975)

The Miller Center. Chester A. Arthur (1829 – 1886)

National Park Service. Chester Arthur’s Civil War

Michael J. Gerhardt. The Constitutional Significance of Forgotten Presidents, 54 Clev. St. L. Rev. 467 (2006)

Katherine Greider. The Schoolteacher on the Streetcar, New York Times, 11/13/2005.

Ian Benjamin. Remembering local educator Chester Arthur who became president. The Record, 5/26/2013.

NYS Department of Military and Navel Affairs. Chester as Quartermaster – Original Letters.

Ben Perley Poore. Chester Alan Arthur, 7 The Granite Monthly: A Magazine of Literature, History and State Progress 265 (1884)

Eugene Virgil Smalley. The Republican Manual: History, Principles, Early Leaders, Achievements of the Republican Party: with Biographical Sketches of James A. Garfield and Chester A. Arthur (1880)