1789-1865

Court of Appeals, 1847-1850; 1854-1855

Chief Judge: 1851-1853

by Albert M. Rosenblatt

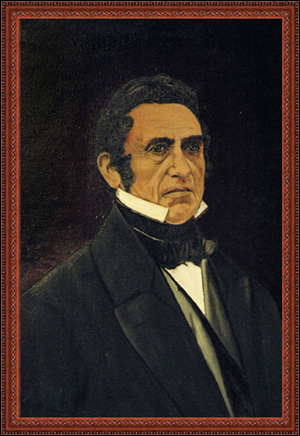

Judge Charles Ruggles has a special place in this writer’s heart because he was at the center of an adventure that spurred my interest in the history of the Court of Appeals. Early in 1997, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye was making preparations for the 150th anniversary of the court’s history. An inventory revealed that the Court had oil paintings for every Chief Judge except for Judge Ruggles, who served on the Court’s first bench in 1847 and as its second Chief Judge from 1851 to 1855.

Chief Judge Kaye called me and asked if I could help locate at least a likeness of the judge, who had ties to Dutchess County, where I live. With relish, I took on the job, believing it would fall easily within the province of anyone who, like myself, was a member of the Baker Street Irregulars-a society dedicated to the exploits of Sherlock Holmes, the world’s first consulting detective.

I should have realized that if she and her capable researchers, led by the tireless Frances Murray, had not found Judge Ruggles, the task would not be easy. Investigators say of homicides that if the crime is not solved within the first few hours, it becomes increasingly harder, and I came to feel much the same about the quest for Judge Ruggles. Days turned into weeks; obituaries, school records, and historical societies turned up no likeness, and the scores of letters that I wrote produced barely a couple of false starts. My partner, Jack Gartland, a local attorney who shared my sense of history, and I were all but ready to conclude that no image existed until we received a call from Stuart W. Lehman, historic site assistant at the Senate House State Historic Site in Kingston. In response to one of my letters, Lehman had discovered a small photograph of Ruggles in the Roswell Randall Hoes collection1 at the Senate House. Judging by the correspondence in the file, someone else, years before me, had been looking for Judge Ruggles’ picture. On September 5, 1918, Hoes had written to the Court, asking about a picture, and the Court’s librarian, Edgar Murlin wrote back that the Court did not have one, nor did the State Library. We do not know how the enterprising Hoes located a picture, but he did, and from it, Lehman inferred, produced a small daguerreotype that had been quietly reposing for decades in a folder at the Senate House.

Jack Gartland, who headed Poughkeepsie’s McCann Foundation, commissioned a Hudson Valley artist, Ron Costello, to paint an oil portrait from the daguerreotype, and we presented it to the Court on August 27, 1997, in time for the 150th anniversary.

* * * * * * * * * * * *

About six days after electors chose George Washington as the nation’s first president, Charles Herman Ruggles was born in New Milford, Connecticut, the son of Joseph Ruggles (1757-?), a Revolutionary War soldier, and Mary Warner. He was a cousin of Samuel Bulkley Ruggles (1800-1881), who founded Gramercy Park in New York City. The Ruggles family has been traced back to Staffordshire in the 12th Century, during the reign of King Henry II.

Young Ruggles went to Kingston, New York, to study law with Samuel Hawkins, a relative. In 1817, he formed a partnership with Abraham Bruyn Hasbrouck2 which lasted until about 1831. Hasbrouck later became president of Rutgers College.3 In 1828, Hasbrouck employed a domestic helper named Isabella, who later became known as Sojourner Truth. Her son had been taken from her and sold into slavery. Ruggles and Hasbrouck were among those who apparently, for no fee, helped Isabella get her son back from Alabama.4 That year Ruggles was appointed Ulster County district attorney.5

During the partnership, Ruggles served in the New York State Assembly in 1820, and in the 17th Congress from March 1821 to March 1823. In 1827, he married Gertrude Beekman, who died the following year. Ruggles began his judicial career when Governor Enos T. Throop named him to the Supreme Court for the old Second District (some writings refer to this as the Second Circuit) in 1831, where he also served as Vice-Chancellor. In 1845, he aged out of that position owing to the mandatory retirement for 60-year-olds. That “retirement” was good for Judge Ruggles, whose greatest accomplishments took place after he had reached three score.

In 1846, the State held its Constitutional Convention, which was particularly important to the judiciary, Judge Ruggles, by common consent, was named to head the committee appointed to create a new judicial system.6 He gained respect and admiration of his convention colleagues and made substantial contributions in several of the constitutional initiatives.7

As judiciary chairman, he was highly effective, as one commentator reported:

“Ruggles was a simple-hearted and wise man. He had been on the Supreme bench for fifteen years, becoming one of the distinguished jurists of the State. In the fierce conflicts between Clintonians and Bucktails he acted with the former, and then, in 1828, followed DeWitt Clinton to the support of Andrew Jackson. But Ruggles never offended anybody. His wise and moderate counsel had drawn the fire from many a wild and dangerous scheme, but it left no scars. Prudence and modesty had characterised his life, and his selection as chairman of the judiciary committee disarmed envy and jealousy. He was understood to favour an elective judiciary and moderation in all doubtful reforms.”8

His success at the convention earned him the nomination for a seat on the newly formed 1847 Court of Appeals. He was elected and served for six years, became Chief Judge in 1851, and continued in that capacity until 1853.

In May 1850, after having been widowed for over 20 years, he married Mary Crooke Broom Livingston (1804-1877), the widow of Edward Philip Livingston (1780-1843). In the Poughkeepsie Adriance Library, there is a file on the Ruggles family. Although it does not contain a likeness of the judge, it has one of Mary Crooke Broom Livingston. Years before she married Judge Ruggles, she happened to be seated in the gallery of the Senate Chamber of the Capitol when widower Edward Livingston, then Lt. Governor of New York, saw her and was struck by her beauty. She was “reckoned the most beautiful girl in all this region.” They were married in 1832 and lived at “Clermont,” the Livingston homestead in Columbia County, now a historic site. After Livingston’s death, she married Judge Ruggles, and they lived at “Brookside” in Poughkeepsie. Her portrait is also at the Henry Luce III Center in Washington, D.C.

As an associate judge, he took ill in 1855 and after having missed the June and September terms, resigned in October 1855. He died ten years later on June 15, 1865, after a relatively inactive decade. The accounts of his passing leave no question that he was a revered figure in the community and the state judiciary. In 1940, Chief Judge John Loughran presented a paper at the Ulster County Historical Society at Winnisook Lodge, reviving the memory of Judge Ruggles, who had been dead for 75 years. He captured Judge Ruggles nicely, remarking that his “judgments abound in plain statements. There is no purple passage. There is much of logic and nothing in metaphor. What shines out is rare common sense and courage and independence.”9

In Doty v. Brown (4 NY 71 [1850]), Judge Ruggles authored one of the Court’s early expositions of the preclusive effect of an earlier determination between the parties. He said:

“The question of fraud was tried between these same parties in the former suit before Justice Tracy, and there determined against the validity of the bill of sale. . . .

“[T]he settled principle of law appears to be that the same point or question, when once litigated and settled by a verdict and judgment thereon, shall not again be contested in any subsequent controversy between the same parties depending on that point or question.”10

In Silsbury & Calkins v. McCoon & Sherman (3 NY 379), Judge Ruggles revealed his scholarly side in reviewing the legal history of the trespass to chattels, which considered remodeling property altered its original character. He expressed the point lucidly at the outset of the decision:

“It is an elementary principle in the law of all civilized communities, that no man can be deprived of his property, except by his own voluntary act, or by operation of law. The thief who steals a chattel, or the trespasser who takes it by force, acquires no title by such wrongful taking. The subsequent possession by the thief or the trespasser is a continuing trespass; and if during its continuance, the wrongdoer enhances the value of the chattel by labor and skill bestowed upon it, as by sawing logs into boards, splitting timber into rails, making leather into shoes, or iron into bars, or into a tool, the manufactured article still belongs to the owners of the original material, and he may retake it or recover its improved value in an action for damages.”11

The case involved the theft of plaintiff’s corn, which was stolen and made into whiskey. In holding that the ownership of the whiskey remained in the plaintiff, Judge Ruggles drew on Justinian’s digest and Puffendorf’s Law of Nature and Nations. The United States Supreme Court cited Silsbury,12 as have legal commentators in law reviews.13

In another instance, Ruggles’ teaching as to taxation was featured in the American Law Review.14 The article cited The People v. The Mayor of Brooklyn (4 NY 410), in which Judge Ruggles distinguished between the taking of property under the power of eminent domain and under the taxing power, said:

“Private property may be constitutionally taken for public use in two modes: that is to say, by taxation and by right of eminent domain. These are rights which the people collectively retain over the property of individuals to resume such portions as may be necessary for public use. The right of taxation and the right of eminent domain rest substantially on the same foundation.”15

After declaring that both powers have essentially the same basis and that under each the taking is for public use, he stressed the distinction between them, saying:

“Taxation exacts money or service from individuals as, and for their respective shares of contribution to any public burden. Private property taken for public use by right of eminent domain is taken, not as the owner’s share of contribution to a public burden, but as so much beyond his share.”16

Judge Ruggles’ other notable writings include DePuyster v. McMichael (6 NY 467 [1852]), involving the doctrine of tenures, and Barto v. Himrod (8 NY 483 [1853]), as to whether the law-making power that the Constitution had committed to the Legislature could be remitted by law to the electors at large.

The most momentous and surely the most publicized decision Judge Ruggles wrote related to the Erie Canal. The canal has been one of the world’s most important waterways, propelling New York State into the center of the nation’s commercial life. From its inception in 1825, canal traffic had become so great by 1835 that enlargement was called for. The Constitution of 1846, however, prohibited the Legislature from incurring a debt in excess of one million dollars. When the Legislature attempted to avoid the restriction by pledging the income of the canal in advance, claiming it would not incur a debt, litigation ensued, and Judge Ruggles authored the opinion for the Court. (It is worth remembering that he was a delegate to the Constitutional Convention of 1846.)

The case began after the Legislature, in 1851, passed a law directing the Comptroller to issue nine million dollars of six percent canal revenue certificates to enlarge the canal and complete the Genesee Valley and Black River canals. No referendum was held, and the State disclaimed any potential liability for the debt. Samuel Tilden attacked the Act, declaring it an evasion of the law. Writing for a majority of the Court of Appeals in Newell v. People (7 NY 9 [1852]), Chief Judge Ruggles cited the constitutional provisions requiring that the canal “remainder” be applied “in each fiscal year” to the Erie enlargement and the completion of the Genesee Valley and Black River canals. These provisions, he said, established a constitutional requirement that the canal work be financed on a “pay as you go” basis as revenues became available. Because nine million dollars was to be borrowed as the work progressed, Judge Ruggles ruled that the constitutional mandate requiring application of the canal remainders “in each fiscal year” had been violated. He made the point clearly: “[t]he chief object of the restraint imposed by the [referendum requirement] of the constitution, upon the contracting of public debt, was to protect the people against the exhausting burthen [sic] of paying interest.”

Newell was a centerpiece of a 1921 Cornell Law Review article17 in which the authors observed that Judge Ruggles “was impressed with the argument that the debt was not debt within the meaning of the constitutional prohibition since it was not backed by the general credit of the state but was restricted to a special fund. . . . [He] was also unpersuaded that the disclaimer provision changed the tenor of the transaction.” The disclaimer, he said, would eventually be undone.

As one might expect, the decision drew considerable news coverage and commentary.18 On February 15, 1854, the voters resoundingly voted to amend the Constitution to increase the debt limit and go forward with the canal enlargement. In New York City, the vote (early returns) was 10,141 for, 2,346 against. In Buffalo, the vote was 10,250 for, and five against.19

As with so many others of our early judges, we know little of their personalities and are relegated to the cold pages of biographical accounts, dates of office, and the like. In Judge Ruggles’ case, we have a bit more by way of letters to and from him in the Ruggles family folder at the Poughkeepsie Adriance Library. One in particular, dated February 11, 1823, is revealing, written when he was a 34-year-old congressman. I infer that he was writing to his wife-to-be, Gertrude Beekman, describing the tiresome speech he was made to endure. His writing showed wit and charm. I wish I could have met him.

In the Ruggles folder at the Senate House, a one-page narrative accompanies the small picture. It was written by Duane E. Fox:20

“The head is of a type that indicates a well balanced combination of the vital and the intellectual qualities. The forehead, while ample, is not aggressively so but seems to spring like an arch from the eyebrows toward the top of the head. Although not visible in the picture, one is led to vizualize a strong development of the lower back head, indicating the driving power to carry the mental processes into effect. A vigorous growth of hair, somewhat disposed to curl, gives a further impression of abundant vitality.

“The eyes seem to require to be shown the reason of things. They are not unsympathetic but rather critical. If the face were that of a physician, I should expect him to excel as a diagnostician; if an engineer, he would look carefully to the qualities of his materials and the stresses and strains to which they were to be subjected; if a lawyer I should expect him to be of the conservative type but not hide-bound by precedent as against a clear showing of a reason contra; if a clergyman, I should expect him to stand by the ancient faith but not to be the last to cling to the doctrine of infant damnation.

“The nose is prominent and shapely, giving dignity, in connection with the eyes and brow, to the entire countenance. The features named contribute the most pleasing portion of the face.

“Below the nose the features do not seem altogether to belong to the same countenance. The chin is not prominent or strong and might indicate some weakness, were it not counterbalanced by the stronger features above. The mouth indicates to me a conscious or unconscious effort to over balance any such possible weakness. The lips are compressed, artificially so, it seems, and reveal an effort of repression that may be foreign to the native disposition but which, by the experiences of life and action, has been found necessary.”

Quite an assessment, and from what we know of Judge Ruggles, close to the mark.

Progeny

Judge Ruggles had no children.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Biographical Directory of the United States Congress, p. 1750.

Chester, Alden, Courts and Lawyers of New York, 1925, Vol. 2, pp. 679, 694, 806, 849.

Chester, Alden, Legal and Judicial History of New York, Vol. I, National Americana Society, New York, 1911, p. 358. Also, Vol. II, p. 116.

Clearwater, A. T., History of Ulster County, p. 485.

Code Relating to the Poor in the State of New York, Albany, 1870, State Inebriate Asylum, ‘ 1832.

Dutchess County Bar Newsletter (The Advocate), Oct./Dec. 1998.

Dutchess County Historical Society records.

Green Bag Vol. II, No. 7, July 1890, by Irving Browne, p. 280, very brief sketch.

Hammond, Jabez D., The History of Political Parties in the State of New York from the Ratification of the Federal Constitution to December 1840, 4th Ed., Syracuse, 1852, pp. 290, 348.

Hughes, Larry, Elusive Judge Finally Gets Picture Nailed, Poughkeepsie Journal, Sept. 1, 1998, p. E1.

Lincoln, Charles Z., Vol. II.

Mabee, Carlton, Sojourner Truth, New York, 1993, pp. 18, 38, 251.

McAdam, David, History of the Bench and Bar of New York, Vol.1, New York History Co. (1897), p. 466, very short bio.

Minute Book of the Vestry of Saint Paul’s Church in Poughkeepsie, New York, Aug. 22, 1835.

National Cyclopaedia, p. 335.

New York Public Library Rare Books and Manuscripts Division. Collection of Correspondence, Accounts, and land papers (one box).

New York Times, Aug. 20, 1855, p. 1 (resignation).

New York Times, Jan. 3, 1854, p. 6, election returns.

Obituary, Kingston Journal, June 21, 1865.

Platt, Edmund, History of Poughkeepsie, Poughkeepsie, New York, Dutchess County Historical Society, 1987, p. 123.

Poughkeepsie Daily Eagle, June 16, 1865; June 20, 1865.

Proceedings of the Ulster County Historical Society 1939-1940, speech by Judge John T. Loughran, “Life of Judge C. H. Ruggles,” pp. 29-39.

Ruggles, Henry Stoddard, The Ruggles Family of England and America, privately printed, 1896.

Schoonmaker, Marius, The History of Kingston, New York, Burr Printing House, 1888, p. 449.

Smith, James H., History of Dutchess County, Interlaken, NY, pp. 122, 464.

Smith, R. B., History of the State of New York Political and Governmental, Vol. II, by Willis F. Johnson, Syracuse, NY, The Syracuse Press, 1922, p. 398.

Sylvester, N. B., History of Ulster County 1880, p. 105.

Who Was Who, History Volume, p. 528.

Published Writings

Opinions of the Judges of the Court of Appeals on the Constitutionality of the Canal Act, Albany, H. H. Van Dyck, 1852.

Address to the public by the Lackawaxen Coal Mine and Navigation Company, relative to the proposed canal from the Hudson to the headwaters of the Lackawaxen River, New York, Wm. Gratten, 1824.

Endnotes

- Hoes (1850-1921) a United States Navy Chaplain, was a prolific collector of historical records, including those relating to Ulster County. His collection of materials relating to the Spanish-American War is at the Library of Congress.

- New York Times obituary of Abraham Bruyn Hasbrouck, Feb. 25, 1879.

- M. Schoonmaker, History of Kingston, New York, Burr Printing House, 1888, p. 449.

- C. Mabee, Sojourner Truth, New York, New York University Press, 1993, p. 18.

- Id, 251.

- In Memoriam, 32 NY (5 Tiffany) 17-19, June 16, 1865.

- See, Charles Z. Lincoln, The Constitutional History of New York.

- Alexander, DeAlva S., A Political History of the State of New York, Vol. II, New York, Henry Holt and Company, 1906, p. 109-110.

- Kingston Daily Freeman, Sept. 21, 1940.

- Doty v. Brown, 4 NY 71, 72-74 (1850).

- Silsbury & Calkins v. McCoon & Sherman, 3 NY 379, 381-384.

- Union Naval Stores Co v. United States, 240 US 284, 291 (1915).

- Kull, Symposium: Private Law, Punishment, and Disgorgement: Restitution’s Outlaws, 78 Chi Kent L Rev 17; D. Friedmann, Restitution and Unjust Enrichment: Restitution for the Wrongs: The Measure of Recovery, 79 Tex L Rev 1879.

- 5 Am L Rev 126, 143 (1870-1871).

- Summary of Events, 5 Am. L. Rev. 126, 143 (1870) (quoting People ex rel. Griffin v. Mayor of Brooklyn, 4 NY 419, 422-423 [1851]).

- Id. (quoting People ex rel. Griffin, 4 NY at 424).

- W. J. Quirk and L. E. Wein, A Short Constitutional History of Entities Commonly Known as Authorities, 56 Cornell L. Rev. 521 (1921).

- See, e.g., The Canals, The Law Declared Unconstitutional! New York Times, May 13, 1852, p. 2; The State Constitution, New York Times, May 28, 1852, p. 2; Canal Interests, New York Times, June 2, 1852, p. 2.

- Election Returns. Constitutional Amendment Triumphant, New York Times, Feb. 16, 1854, p. 1.

- This reporter does not know much about Duane E. Fox or why he came to write the piece. A computer search reveals that a lawyer named Duane E. Fox argued many cases before the United States Supreme Court around the turn of the last century.