In his seminal work, The Nature of the Judicial Process, U. S. Supreme Court Justice and former Chief Judge of the New York Court of Appeal Benjamin Nathan Cardozo wrote of the land of mystery when constitution and statute are silent, and the judge must look to the common law for the rule that fits the case. He is the “living oracle of the law” in Blackstone’s vivid phrase.

The New York jurist Chancellor James Kent, known as the father of American jurisprudence, described the process by which the common law grew into use by gradual adoption, and received, from time to time, the sanction of the courts of justice, without any legislative act or interference. It was the application of the dictates of natural justice, and of cultivated reason, to particular cases. In the just language of Sir Matthew Hale, the common law of England is “not the product of the wisdom of some one man, or society of men, in any one age; but of the wisdom, counsel, experience, and observation, of many ages of wise and observing men.

Our present New York Constitution, the fifth since the inception of the State, Article 1, Section 14 provides that the law of the State consists of:

Such parts of the common law, and of the acts of the legislature of the colony of New York, as together did form the law of the said colony, on the nineteenth day of April, one thousand seven hundred seventy-five, and the resolutions of the congress of the said colony, and of the convention of the State of New York, in force on the twentieth day of April, one thousand seven hundred seventy-seven, which have not since expired, or been repealed or altered; and such acts of the legislature of this state as are now in force, shall be and continue the law of this state, subject to such alterations as the legislature shall make concerning the same. But all such parts of the common law, and such of the said acts, or parts thereof, as are repugnant to this constitution, are hereby abrogated.

So, the common law is organic and every day, judges working in courtrooms throughout New York State continue a judicial process that began over fifteen hundred years in Anglo-Saxon England. Their cumulative wisdom builds New York common law year by year, a heritage that will continue beyond their lifetimes to generations yet unborn. How utterly fascinating!

In this series of postings, I plan to look at the sources of this almost mystical body of law as it emerged in Anglo-Saxon England, and follow it through the centuries to 1776, the final year of the Colony of New York. This journey will lead us to the Constitutional Convention held at Kingston in 1777 when our Founding Fathers enshrined the common law in the Constitution of New York State.

Anglo-Saxon scholar, Patrick Wormauld urges that we bear in mind that the Dooms were never intended to represent the complete body of law that existed contemporaneously, and warns that “the King’s Word had permanent significance but only within the limitations of any verbal communication: that is, absolute integrity was dependent upon memory, and was subject, as such, to adjustment, both conscious and subconscious. Written legislation was a useful aid to memory, and sometimes an impressive manifestation of the civilized status of its royal author, but it was not binding, like modern statute law.”

Part 1: The Dooms of the Kingdom of Kent

King Ethelbert (c. 560–616 AD)

The early settlements in England of the Angles and Saxons were organized through customary law preserved by oral tradition. Legal historian Frederick Maitland states that the Maegth (kindred) was “the unit of the common weal, controlling it members in many ways, and answerable for them in matters of both public and private right…A man’s kindred are his avengers; and, as it is their right and honor to avenge him, so it is their duty to make amends for his misdeeds, or else maintain his cause in fight” [blood feud]. Maitland continues “We have to conceive, then, of the kindred not as an artificial body or corporation to which the State allows authority over its members in order that it may be answerable for them, but as an element of the State prior to the State itself. There is a constant tendency to conflict between the old customs of the family and the newer laws of the State; the family preserves archaic habits and claims which clash at every turn with a development of a law abiding commonwealth. Step by step, as the power of the State waxes, the self-centered and self-helping autonomy of the kindred wanes. Private feud is controlled, regulated, put, one may say, into legal harness; the avenging and the protecting clan of the slain and the slayer are made pledges and auxiliaries of public justice.”

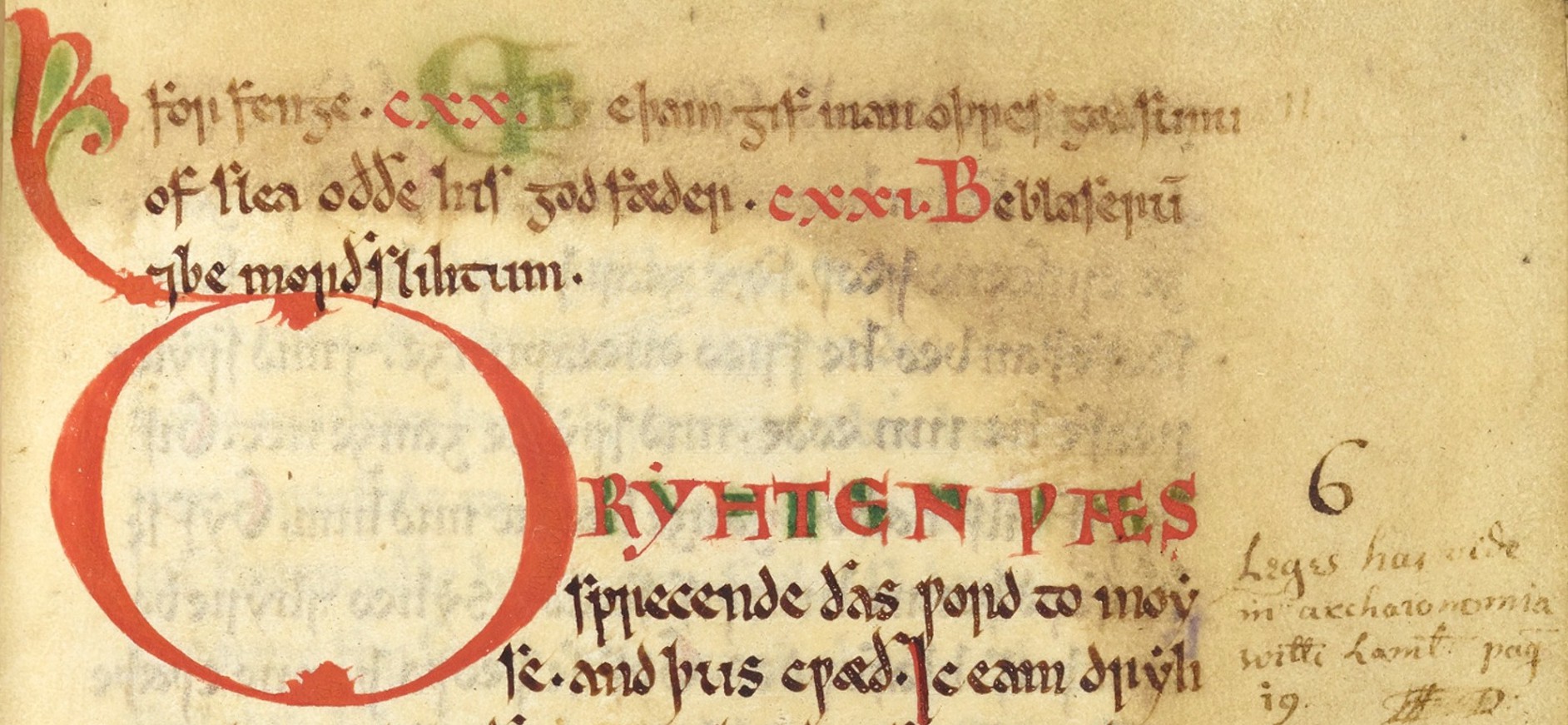

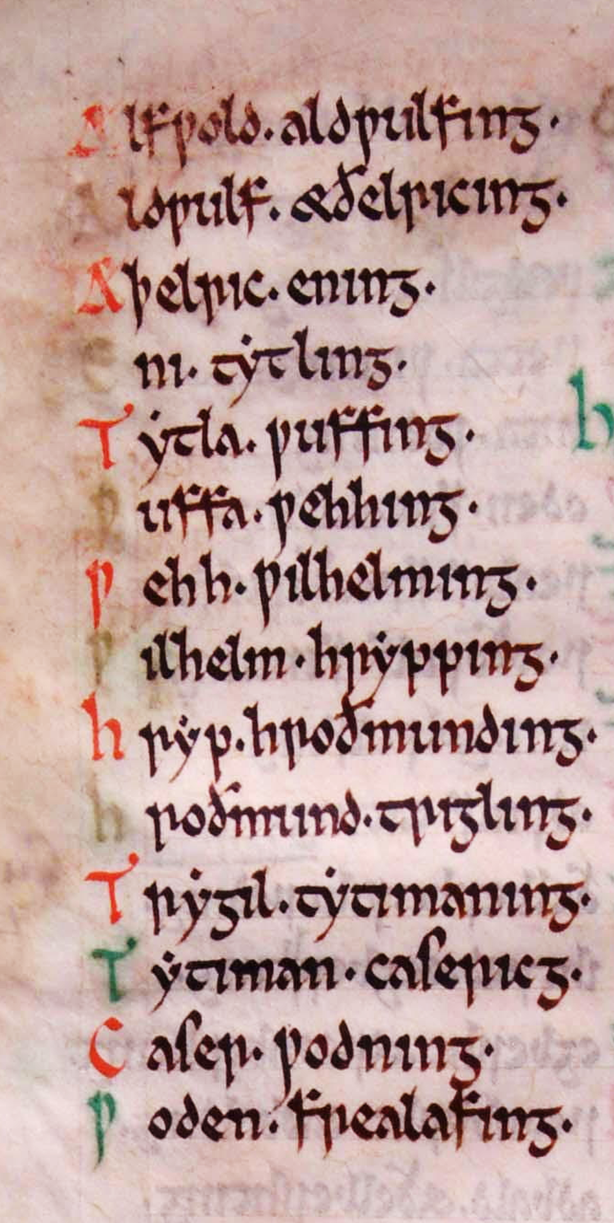

Ethelbert came to the kingship of Kent in the year 560. His kingdom consisted of all the lands to the south of the river Humber. In 596, Pope Gregory the Great sent a group of monks to Kent by under the leadership of Augustus, prior of the monastery of St. Andrew in Rome, and Augustus converted Ethelbert to Christianity. Because the missionaries were also scribes, they introduced the written word into Anglo-Saxon England. In 602, Ethelbert and his Witan (council) issued the Dooms of Ethelbert, the earliest written code in any Anglo-Saxon realm. The Dooms were based on the customary law then in force in Kent and the text survives as a 12th Century copy manuscript, known as the Dooms of Ethelbert, the earliest written code in any Anglo-Saxon realm. The Dooms were based on the customary law then in force in Kent and the text survives as a 12th Century copy manuscript, known as the Textus Roffensis.

The Dooms contain ninety clauses written in old English and they reveal the complexity of Anglo-Saxon culture. The first several dooms deal with the rights of the new church but the remainder of the code is focused on crimes and breach of the king’s peace. The Dooms are essentially a restatement of existing Anglo Saxon legal custom, listing the wergild (tariff) to be paid by a wrongdoer in compensation for harm done to others. Ethelred’s Dooms shows a society that was moving beyond blood feud to a formal system of fixed payments by the wrongdoer to both the King and the injured party or his Maegth (kindred). Scribes replicated the Dooms and the documents were sent to the folkmoots––community gatherings that conducted local affairs and administered justice. Unfortunately, Ethelbert’s Dooms make no mention the judicial procedure that applied in the folkmoot acting in its judicial capacity.

King Hlothhere (615-685 AD) and King Eadric (662-686 AD)

The Dooms of Hlohhere and Eadric, issued in 685, augment the Dooms of Ethelbert. The Hlothhere and Eadric code contains both substantive and procedural dooms. One of the substantive dooms relates to family law and shows the influence of Christian church. The provision allowed a mother to have custody of her children in the event of the death of her husband but retained the customary practice of placing much of the family’s estate in the control of the father’s Maegth. Contract law appears for the first time in the written code–– that dome required witnesses to a sale so that if the sale were later disputed, the witnesses could “declare on the alter” the details of the purchase. If they would not take the oath, the property returned to the party claiming ownership.

King Wihtred (670-725 AD)

The Dooms of Wihtred re issued in 695 and were the last of the Kentish Domes. The king’s Witan and the Council of the Catholic Bishops both approved the code. New provisions “related explicitly to the religious rights and privileges of the church in England, as well as to the obligations of the Anglo Saxon people to adopt Christian principles” (Tucker), and condemned such practices as “irregular marriage” These Dooms have added significance because in this document we find the initial development of concept of statutory enactment.

Sir Frederick Pollock, Frederic William Maitland. The History of English Law Before the Time of Edward I: Volume I (1895)Charles E. Tucker, Jr. “Anglo-Saxon Law: Its Development and Impact on The English Legal System” 2 USAFA Journal of Legal Studies 127 (1991).Charles Gross. The Sources and Literature of English History from Earliest Times to About 1485 (1900).

University of London, Institute of Historical Research. Early English Laws Project. http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/i-atr/