The New York Gazette was founded in 1725 and for many years was the Province’s only newspaper. It was published by the public printer, William Bradford, and was supportive of the Governor and his administration. When New York’s Chief Judge Lewis Morris issued a dissenting opinion in the 1733 case of Cosby v. Van Dam, Governor William Cosby summarily removed Morris from office. Morris and close allies, attorneys James Alexander and William Smith set up the Province’s first independent newspaper, the New-York Weekly Journal. Alexander was the newspaper’s editor and through articles, satire and lampoons, accused the Cosby administration of tyranny and violation of the people’s rights. Governor Cosby resolved to shut down the New-York Weekly Journal.

John Peter Zenger was the newspaper’s printer, one of the few skilled printers in the Province at that time. The Cosby administration determined to take legal action against the printer, perhaps on the assumption that without a printer, the paper could not be published.1 The Governor assigned Daniel Horsmanden, an English barrister newly-arrived in New York, to lead an examination of the newspaper for statements that constituted the crime of seditious libel. Seditious libel was defined as the intentional publication, without lawful excuse or justification, of written blame of any public man or of the law, or any institution established by the law.2 Two separate grand juries were empaneled, one in Spring, 1734, and the other in the Fall of that year. Evidence of seditious libel was presented to both but neither grand jury would issue an indictment against John Peter Zenger.

Next, Governor Cosby determined to use the power of the governmental censorship to hinder the publication of the New-York Weekly Journal. He requested that the Assembly order the public hangman to ceremonially burn issues of the newspaper.3 The popularly-elected Assembly refused to issue the order. The Governor’s Council then ordered the sheriff to have the papers publically burned but when the sheriff applied to the Court of Quarter Sessions (a court of aldermen) for an order authorizing the burning, the court adjourned without entering the order and the public hangman could not proceed.4

The Cosby administration then resolved to proceed against Zenger by an information, a legal procedure, highly unpopular in the Province, that allowed a prosecution to proceed without a grand jury indictment. The Attorney General, Richard Bradley, acting on behalf of the Crown, filed an information before the Supreme Court of Judicature.5 Pursuant to the information, Cosby’s allies on the court, Chief Justice James De Lancey and Justice Frederick Philipse, issued a bench warrant for the arrest of John Peter Zenger. On November 17, 1734, the sheriff arrested Zenger and took him to New York’s Old City Jail.

Zenger’s attorneys, James Alexander and William Smith, sought a writ of habeas corpus and Zenger was brought before Chief Justice De Lancey who ordered a hearing for November 23, 1734. At the hearing, the court set bail at £400, an amount far in excess of Zenger’s means. Unable to post bail, Zenger was returned to jail pending his trial.

Defending Zenger against the charge of seditious libel presented challenges for the defense attorneys. Their main difficulty was that the truth of the published statements was immaterial. Further, the role of the jury in a seditious libel case was limited to deciding whether the person charged was responsible for the allegedly libelous statement. If the jury found in the affirmative, Justices De Lancey and Philipse, close allies of Cosby, would examine the text to determine if the statements constituted seditious libel.

At Zenger’s arraignment in April, 1735, his counsel challenged the validity of the judicial tribunal. Zenger’s attorneys asserted that Governor Cosby’s summary removal of Chief Justice Lewis (in 1733) had been improper, and thus De Lancey’s subsequent appointment as Chief Justice was invalid.6 Zenger’s attorneys also challenged the commissions of the other judges of the court because those appointments were “at the Governor’s pleasure.” The court refused to allow this argument, and Chief Justice De Lancey was heard to exclaim, “You have brought it to that point that either we must go from the bench or you from the bar.”7 Counsel refused to withdraw the assertions and, on April 16, 1735, the court issued an order striking the names of James Alexander and William Smith from the list of attorneys admitted to practice before the Supreme Court of Judicature.

Zenger, left without legal representation, petitioned the court to appoint a lawyer for him. John Chambers, a young, newly-admitted attorney and Cosby loyalist, was assigned to conduct Zenger’s defense. Contrary to expectations, Chambers acquitted himself well in his defense of Zenger — twice, he challenged the lists from which the jury was to be chosen and in doing so, he ensured that the jury empaneled to hear the case was not biased against Zenger. The names of the jurors were: Thomas Hunt (Foreman), Harmanus Rutgers, Stanley Holmes, Edward Man, John Bell, Samuel Weaver, Andries Marschalk, Egbert van Borsom, Benjamin Hildreth, Abraham Keteltas, John Goelet and Hercules Wendover.

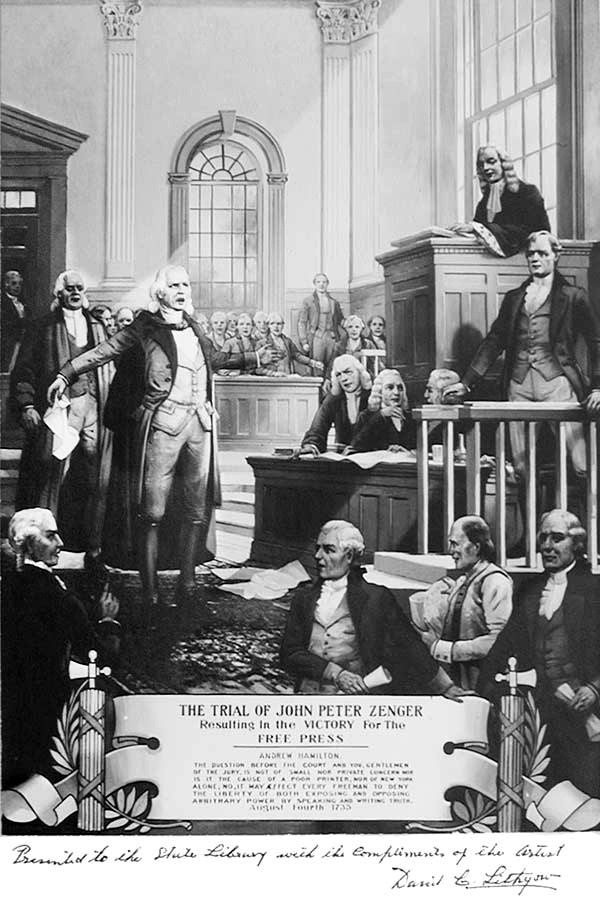

Chief Justice De Lancey adjourned the court until August 4,1735, to give Chambers an opportunity to prepare his case. This provided Zenger’s allies the opportunity to secure for the printer representation by the pre-eminent colonial attorney, Andrew Hamilton of Philadelphia. When the trial commenced in the courtroom on the second floor of City Hall on August 4, Attorney-General Richard Bradley stated the substance of the “information” and in response, John Chambers entered a plea of “not guilty” on behalf of his client. He then described clearly the nature of the case, the necessity that the Attorney General prove who was responsible for the libel, and his expectation that the Attorney-General would fail in his proof. At the close of Chambers’s speech, Andrew Hamilton rose on behalf of Zenger and preempted Attorney General Bradley’s case by admitting that Zenger had published the journals as alleged. In his address, Hamilton asked the jury to consider the truth of the statements published and concluded with these famous words:

The question before the Court and you, Gentlemen of the jury, is not of small or private concern. It is not the cause of one poor printer, nor of New York alone, which you are now trying. No! It may in its consequence affect every free man that lives under a British government on the main of America. It is the best cause. It is the cause of liberty.

Immediately, Chief Justice De Lancey instructed the jury that they, the jurors, should decide only the question of whether Zenger had published the issues of the New-York Weekly Journal. Despite the instruction, the jury, after a brief deliberation, found Zenger “not guilty” of publishing seditious libel. Cheers rang out in the crowded courtroom. Andrew Hamilton’s success was celebrated by a dinner in his honor at the Black Horse Tavern, his departure was marked by a salute of cannons and, in 1735, he was presented with the freedom of the City. John Peter Zenger was released from prison the day after the trial. He returned to his printing business and published an account of his trial.

It is important to note that the Zenger case did not establish legal precedent in seditious libel or freedom of the press. Rather, it influenced how people thought about these subjects and led, many decades later, to the protections embodied in the Unites States Constitution, the Bill of Rights and the Sedition Act of 1798. The Zenger case demonstrated the growing independence of the professional Bar and reinforced the role of the jury as a curb on executive power. As Gouverneur Morris said, the Zenger case was, “the germ of American freedom, the morning star of that liberty which subsequently revolutionized America!”8

| The Tryal of John Peter Zenger The full text of the famous 1736 account of Zenger’s trial. Although it was written from Zenger’s perspective, it is generally believed that it was written by his attorney James Alexander. |

The Trial of John Peter Zenger A play in five scenes |

Sources

Paul Finkelman. Politics, the Press, and the Law: the Trial of John Peter Zenger in American Political Trials Michal R. Belknap (ed). Connecticut (1994)

Donald A. Ritchie. American Journalists: Getting the Story. New York (1997)

Eben Moglen. Considering Zenger: Partisan Politics and the Legal Profession in Provincial New York, 94 Columbia Law Review 1495 (1994)

Endnotes

1) This proved not to be the case. Zenger’s wife, Anna, and his apprentices continued printing the paper. Only one issue was missed. The continued publication of the newspaper built support for Zenger cause.

2) Zechariah Chafee, Jr. Free Speech in the United States (1941)

3) In Tudor and Stuart England, the ceremonial burning of books and other printed material by the public hangman symbolically reinforced the power of the government to restrict freedom of expression.

4) The Sheriff, with several officials loyal to the administration in attendance, had the papers burned in public by his personal servant.

5) As such, this case is also referred to as Attorney General v. John Peter Zenger; either reference is correct.

6) At a later date, the Lords of the Board of Trade in London would decide that Cosby’s removal of Chief Judge Lewis Morris without an inquiry, had been illegal.

7) Maturin L. Delafield. William Smith, Judge of the Supreme Court of the Province of New York. Reprinted from”The Magazine of American History,” of April and June, 1881

8) Statesman, founding father and grandson of Chief Judge Lewis Morris.