In 1916, Europe was in armed conflict and the United States was poised to enter what would be World War I. At the time, Judge Emory A. Chase was 62 years old, serving on the Court of Appeals. On June 24, 1916, he went into the armory of Company E, Tenth Infantry in Catskill and declared his intention to join the depot unit there.1 He was said to be as active as a man of 40. His enlistment reflected his sense of duty and patriotism.

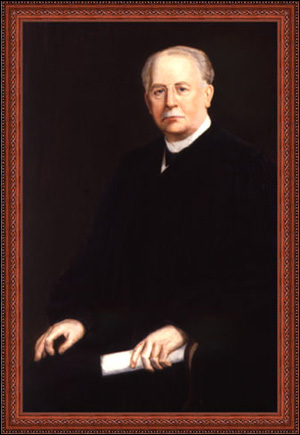

Emory Albert Chase was born on August 31, 1854, in Hensonville, Greene County, New York, the fourth child of Albert Chase (1819-1902) and Laura Orinda Woodworth, daughter of Abner and Betsy (Judson) Woodworth. After their marriage, on September 1, 1844, Judge Chase’s parents moved to Hensonville where Albert Chase ran a lumber and contracting business, serving as a justice of the peace and for 26 years superintendent of the Hensonville Sunday School.

Judge Chase was a descendant of Thomas Chase, who came to America from Hundrich Parish, Chesham, Buckinghamshire, England, and settled in Hampton, New Hampshire, in 1636. There are seven generations between Thomas Chase and Judge Chase, including his great-grandfather Zephania Chase (1748-?), who served in the Revolutionary War.2

As a lad in his late teens, Emory Chase taught at Village Schools in Greene County, working summers at his father’s farm and at carpentry. In 1877, he went to Catskill to study law with Rufus King and Joseph Hallock, and by 1880 was admitted to the Bar. Two years after that, he was on the letterhead of Hallock, Jenkins and Chase, later Jennings and Chase. By this time, Chase began to establish himself in the community’s civic affairs, beginning a career that culminated in his reputation as one of Catskill’s most eminent sons.

In 1882, at age 28, he was elected to the Catskill Board of Education and later became its president. Three years later, he married 24-year-old Mary Elizabeth Churchill (1861-1933) of Pratsville, daughter of Addison Jesse Churchill, one-time Sheriff of Greene County. Established in Catskill, Chase rose from one post to another, gaining the respect of the community and a reputation for service and dedication. In 1890, he was elected supervisor, and in the early 1890s was corporation counsel, leaving that position in 1895. In 1894, he was a delegate to the Republican State Convention.3

At age 42 and active in Republican Party circles, he was elected justice of the State Supreme Court for the Third Judicial District in 1896. Reports reveal that he spent $2,963 in the venture, mostly in the form of donations to the Republican Party. His election marked the start of an illustrious judicial career that lasted 25 years, ending with his unexpected death in 1921.

Those years were a mix of judicial, political, and community involvement. He became director of the Tannersville National Bank, the Catskill Savings Bank, the Albany Trust Company, and two fire insurance companies, and trustee of the Christ Presbyterian Church in Catskill; he was in all the very embodiment of the upright, respected, church-going, prosperous, and charitable figure. One can imagine him walking down Catskill’s main street, tipping his hat to well-wishers, who would surely have wanted to be thought of as a friend of Catskill’s first citizen. Eulogies by their nature are laudatory, but when Judge Chase passed on in 1921, the public outpouring was so effusive, and the affection for him so unconditional, that we can safely say that he was matchlessly beloved and admired.

And with good reason. His judicial service was exemplary. He served as a Supreme Court justice for five years and Governor Benjamin B. Odell appointed him to the Appellate Division Third Department, where he served from 1901 to 1906.4

He then began his lengthy tenure on the Court of Appeals, beginning with his designation, by Governor Frank W. Higgins, as an additional judge of the court.5 In 1910, while still a Supreme Court justice serving on the Court of Appeals, he was nominated for another term with the support of both major parties.6

Two years later, he and Frank H. Hiscock were the Republican nominees for two vacancies on the Court of Appeals for the November 1912 election. Both were strongly supported editorially,7 but were defeated by Democratic candidates John W. Hogan and William H. Cuddeback. Judge Chase sought election again, unsuccessfully, in 1913 and 1914. Nevertheless, he remained on the Court of Appeals as an additional judge by gubernatorial appointment. Considering that these appointments ran from 1906 to 1920, through successive governors and with bar association and editorial page sponsorship, it is difficult to conclude that his tenure rested on anything other than merit.

In 1920, Judge Chase had his last-and this time successful-Republican candidacy for the Court of Appeals. He and Frederick E. Crane (who had secured both major party lines) were elected. Abram Elkus, one of the defeated Democrats, would later serve on the court in 1920, by appointment. And so began Judge Chase’s term as an elected member of the court, poised for a lengthy tenure, strong in mind and, from all appearances, in body. But it was not to be. This robust specimen would serve only a year and a half before his sudden and unexpected death. He died on June 26, 1921, in his home on Prospect Avenue in Catskill, in his sleep, felled by a clot of blood at the heart.

Earlier that month, he had authored an important and widely publicized case, People ex rel. Stafford v. Travis,8 upholding New York State’s income tax law against nonresidents.9 The decision, one of his last, was the culmination of notable writings that spanned a quarter century. In all, he wrote 363 majority opinions for the Court of Appeals.

Thanks to Judge Chase, we had Bud Fisher’s “Mutt and Jeff” for as long as we did. In the seminal and oft-cited intellectual property case of Fisher v. Star Co.,10 Judge Chase wrote that those characters had acquired a “secondary meaning” by virtue of their widespread dissemination and popular association with their creator, Bud Fisher. Because of this secondary meaning, Judge Chase and the Court perceived that it would be unfair to both the public and Fisher to allow Fisher’s previous employer to keep publishing Mutt and Jeff cartoons without his approval. Although copyright law did not protect the characters or Fisher’s rights in them, giving Judge Crane a basis for dissent, the Court recognized that such unfair competition should nevertheless be prevented in these circumstances.

In a related vein, it was in another Chase opinion that the Court of Appeals initially recognized a person’s right to prevent the use of their name or likeness by another for commercial purposes. The famous Binns v. Vitagraph Co. case11 involved a dispute that arose from the dramatic reenactment of a shipwreck on the big screen. John Binns, the popular hero of the Republic disaster, sued to recover for the use of his name and likeness in a “moving picture” and in advertisements to promote both the reenactment picture and the other films with which it was shown. Luckily for Binns, New York’s Legislature had passed a law to overturn the Court’s opinion in Roberson v. Rochester Folding Box Co.,12 in which the Court had refused to recognize an equitable privacy right against the use of one’s likeness by another for advertising. The Court has since considerably restricted the scope of right of publicity by way of the “newsworthiness exception,” but Binns undoubtedly remains good law by virtue of Vitagraph’s fictionalization of the events portrayed.13

In the corporations-law arena, Judge Chase gave us Continental Securities Co. v. Belmont,14 in which the Court recognized the stockholders’ derivative cause of action for the fraudulent issuance of stock. That case is often cited for several propositions, including the requirement that shareholders demand board action and demonstrate the futility of that demand prior to suit, as well as the rule that stockholders cannot ratify fraud on the corporation’s creditors.15

In the realm of contract law, Judge Chase is responsible for the classic case of Varney v. Ditmars.16 In that case, over Judge Cardozo’s dissent, the Court ruled that an employer’s promise to give his employee a “fair share” of the profits was too indefinite to create an enforceable contract. Unfortunately for Judge Chase, time has proven more favorable to Judge Cardozo’s belief that there would have been an enforceable contract if the employee had been able to prove damages.17 Also unfortunately for Judge Chase, his dissent in another classic contract case, Patterson v. Meyerhofer,18 rejected what has become an oft-cited example of a contracting party’s implied duty not to interfere with the other party’s good faith performance. Because the plaintiff had brought suit in equity, Judge Chase would have precluded him from recovering contract damages at law in spite of the defendant’s egregious conduct in bidding against the plaintiff at a foreclosure sale where the plaintiff was to purchase real property to sell to the defendant at a profit.

Criminal law theorists are likely familiar with another dissent of Judge Chase’s, in People v. Jaffe.19 The defendant, Jaffe, was convicted of attempted receipt of stolen property in the form of twenty yards of cloth, but the statute that he was convicted under required knowledge of the stolen status of the property be proven in order to sustain a conviction of the completed crime. Jaffe believed he was receiving stolen property, but what he did not know was that at some point the cloth had been returned to its owner and was being used by the police, with the owner’s permission, in an attempt to catch Jaffe red handed — the property was therefore no longer “stolen.” The Court majority considered the case to be one of legal impossibility and reversed the conviction, because if Jaffe had followed through on his intended act no crime would have been committed. Judge Chase, on the other hand, invoked by reference the case of the pickpocket who attempts to steal a wallet but fails only because the pocket is empty, a classic example of factual impossibility that would have required the conviction upheld.20 Judge Chase has since been vindicated by the drafters of the Model Penal Code and the weight of contemporary criminal theory.21

Judge Chase’s life did not quite reach “three score and ten,” but it was a life of rectitude and accomplishment. He is remembered as one of Greene County’s most prominent sons and an illustrious member of the Court of Appeals.

Progeny

Judge Chase was said to be the fourth child of his parents, Albert Chase (1819-1902) and Laura Orinda Woodworth. Biographical accounts, however, mention only a sister, Lydia A., and a brother, Demont (1860-1935). Possibly the other child died young. Judge Chase’s sister Lydia had a son, Albert C. Bloodgood, a prominent Catskill lawyer who died in 1943. The judge’s brother, Demont, was the great-grandfather of Emory L. Chase, who lives in Mayfield (Fulton County), New York, and has three brothers: Jeffrey, Kevin, and Christopher.

Judge Chase’s wife, Mary Elizabeth Churchill Chase, died on March 24, 1933. The Judge and Mrs. Chase had two children. Their daughter, Jessie Churchill Chase (1887-1952), graduated from Smith College and married a Catskill attorney, James Lewis Malcolm (1887-1937). In 1944, she married Dr. Frank P. Graves, who died on September 14, 1956, at age 87. He had been New York State’s Education Commissioner. The judge’s daughter Jessie had no children.

Albert Woodworth Chase, the judge’s son, was born on April 30, 1890. He graduated from Phillips Andover in 1909 and went to Yale. According to Yale records, although he was a junior in 1912, he did not graduate, apparently having gone into the armed forces just before World War I. In 1912, he was also listed as a member of Company D 2nd Regiment, Naval Training Station at Great Lakes Camp in Illinois. In 1918, he was in the United States Navy Flying Corps and was commissioned an aviation ensign on September 20, 1918. On May 14, 1927, he married Alma S. Burgess of Brooklyn. In 1933, when his mother died, he was said to be living in Albany.

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

3:2 The Chase Chronicle (Apr. 1912).

16:1 The Chase Chronicle (Jan. 1926).

Clippings from Scrapbook 114, the Vedder Memorial Library, Coxsackie, NY:

“Death’s Heavy Toll,” Catskill newspaper obituary, July N.D., 1921.

“Bar Association Banquet,” Catskill Recorder, February 23, 1906.

“Judge Chase’s Pictures,” Recorder, Dec. 1, 1911.

History of the Bench and Bar of New York, at 84 85 (New York History Co. 1897, Hon. David McAdam et al. eds.).

In Memoriam, 231 NY 653 (1921).

In Memoriam, Emory A. Chase (The Brandow Printing Co., Albany, NY 1925).

Judge Emory A. Chase Dies In His Sleep, N.Y. Times, June 26, 1921, at 22.

Kimball, The Capital Region of New York State, Crossroad of Empire, 1942 (Transcribed by Arlene Goodwin), at http://www.rootsweb.com/~nygreen2/biohonemoryalbert_chase.htm, from Biographical Review, Vol. XXXII, located at the Durham Center Museum (web site last visited 6/23/05).

Lawyers Entertained, The Examiner, Feb. 20, 1904.

Public Papers of John A. Dix, Governor, 1911, in Thomas Gale, 1 The Making of Modern Law, at 431 32 (1912 13) (designation as Assoc. Judge of the Court of Appeals by Gov. Dix).

Schenectady Digital History Archive, Hudson Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs: Chase, at http://www.schenectadyhistory.org/families/hmgfm/chase.html.

Published Writings Include:

Greene County Courts and Officers, A General Historical View, paper by Judge Chase at the second annual meeting of the Greene County Bar Association in Catskill, New York, February 2, 1904.

Local Historical Gleanings, a paper read by Judge Chase at the Adjourned Eighth Annual Meeting of the Greene County Bar Association, held in Catskill, New York, April 11, 1910.

Endnotes

- New York Times, Jun. 25, 1916, at 5.

- For a history of the Chase family, see www.webnests.com/chase/chronicles/emorychase.htm. The site relates to April 1912, Vol. 2, The Chase Chronicle; see, also, Hudson-Mohawk Genealogical and Family Memoirs: Chase. It is on-line, taken from Vol. I, pp. 462-467 of the Memoirs, edited by Cuyler Reynolds (New York: Lewis Historical Publishing Co., 1911). The Chase-Chase Family Association was incorporated in Hartford, CT, in 1899. Judge Chase was vice-president when the association held its first reunion at the First Religious Society in Newburyport, MA, on August 30, 1900. The Chase Chronicle continued until Vol. 9, July 1918, and possibly thereafter.

- New York Times, Sept. 11, 1894, at 1.

- New York Times, Jan. 9, 1901, at 5.

- New York Times, Dec. 8, 1905, at 1.

- New York Times, Oct. 8, 1910, at 6.

- New York Times, Oct. 10, 1912, at 10.

- 231 NY 339 (1921).

- New York Times, Jun. 3, 1921, at 32.

- 231 NY 414 (1921).

- 210 NY 51 (1913).

- 171 NY 538 (1902).

- See, e.g., Messenger v. Gruner + Jahr Printing & Publishing, 94 NY2d 436 (2000).

- 206 NY 7 (1912).

- See, e.g., 48 ALR3d 595; White, New York Business Entities ” B626.04, PB 708.06, N715.01; Norwood P. Beveridge, Interested Director Transactions at Common Law: Validation Under the Doctrine of Constructive Fraud, 33 Loy. L.A. L. Rev. 97, 121 n.140 (1999).

- 217 NY 223 (1916).

- Cf. U.C.C. 2-204(3); Jonathan Yovel, What Is Contract Law “About”? Speech Act Theory and a Critique of “Skeletal Promises,” 94 Nw. U. L. Rev. 937, 941-42 (2000).

- 204 NY 96 (1912).

- 185 NY 497 (1906).

- 185 NY at 503 (citing People v. Moran, 123 NY 254 [1890]; People v. Gardner, 144 NY 119 [1894]).

- See Model Penal Code ‘ 5.01; Wayne R. LaFave, Criminal Law ‘ 11.5(a)(3), at 600-603 (4th ed.2003).