Introduction

Seventeenth-century settlers in Flushing drafted a protest that became a watershed of religious freedom in the New World. Let’s both put this remarkable piece of paper in context and outline its significance. Flushing—the city in Queens—was originally Vlissingen, after a Dutch city of that name. It was part of the Dutch colony of New Netherland, which stretched across the Middle Atlantic region of what would become the United States. New Netherland is best remembered today for its capital—New Amsterdam—which became New York City, and for its last director, Peter Stuyvesant. The Dutch brought several things to the region they colonized. Most notable was an idea they more or less invented in the seventeenth century: “tolerance.” This idea got transferred to the New World colony.

Its Dutch character is one reason why New York grew into a vibrantly multiethnic culture: one reason why New York became New York. The English of New England undeniably gave us their language and many aspects of government, but they were at this time in American history very far from enunciating such an ideal of religious freedom. What we see in the Flushing Remonstrance is a fledgling American colony applying hard-won rights from the Old Country to a New World setting, where they would flourish in an entirely new way. The mixed peoples who founded New Netherland would become a wellspring of American religious liberty, and also a source of America’s notion of equality.

Excerpted from “The Importance of Flushing” by Russell Shorto in New York Archives (Winter 2008).

Background

The 1640 Charter of Freedoms and Exemptions provided: “And no other Religion shall be publicly admitted in New Netherland except the Reformed, as it is at present preached and practiced in the United Netherlands.” In September 1654, twenty-three Jewish refugees arrived in New Netherland. They came from the Dutch colony in Brazil and had fought with the military arm of the Dutch West India Company in an unsuccessful attempt to defeat the Portugese invasion. Director-General Pieter Stuyvesant was determined to refuse them entry, arguing that “blasphemers of the name of Christ be not allowed further to infect and trouble this new colony.” The Company overrode his objections, and directed that the Jewish refugees be allowed to settle and trade “provided the poor among them shall not become a burden to the [C]ompany or the community, but be supported by their own nation.” Despite this, Stuyvesant The refused the community permission to build a synagogue.

That same year, the Lutherans requested permission to have a minister of their own faith. Stuyvesant refused, stating that his oath to the Company and the States General forbade him to openly tolerate any religion other than the Dutch Reformed church. The Lutherans then appealed to the Company and in response, the Company ordered that no public religious service except that of the true Dutch Reformed Church “should be permitted in New Netherland,” and encouraged the Director-General to use “all moderate exertions…to win Lutherans and other dissenters from their errors.” By an ordinance of February 1, 1656, Stuyvesant restricted the religious practices of all in New Netherland who were not adherents of the Dutch Reformed Church to “the reading of God’s Holy Word, family prayers and worship, each in his own house.”

In 1657, following a two-month voyage in a frail boat, twelve Quakers from Yorkshire, England landed on Long Island. Although the group intended to proceed to New England, two of the women immediately went to New Amsterdam and began preaching in the streets. They were arrested, sentenced and banished from New Netherland. Another of their number, a young man named Robert Hodgson, suffered more barbarous treatment. He was arrested for preaching in the Long Island town of Hempstead and brought before Director-General Stuyvesant. When he refused to doff his hat in court, a Quaker practice indicating respect for God alone, Stuyvesant was outraged and ordered him to be chained to a wheelbarrow and compelled to work on the roads. When the preacher refused to work, the authorities hung him up by the hands and beat him severely. The refusal to work and the beatings continued daily until Hodgson was near death, and the Director-General’s sister, Anna, wife of Nicholas Bayard, interceded. Hodgson was sentenced to banishment and removed from the colony.

Director General-Stuyvesant also introduced ordinances mandating the confiscation of vessels bringing Quakers into New Netherland and imposing a £50 fine on anyone sheltering a Quaker. The settlers in the small town of Vlissingen (now Flushing, Queens), protested against these ordinances in a 1657 petition addressed to the Director-General, known as the Flushing Remonstrance. But the repression continued until a group of New Amsterdam merchants, including Govert Loockermans, urged toleration for the Jews, the Lutherans and the Quakers, alerting the Company to the danger that religious repression would reduce immigration. On April 16, 1663, the Company instructed Stuyvesant to “allow every one to have his own belief as long as he behaved quietly and legally, gave no offence to his neighbors, and did not oppose the government.”

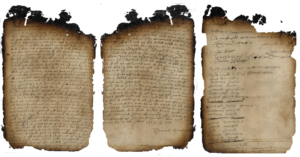

Full Text of the Flushing Remonstrance

Right Honorable

You have been pleased to send unto us a certain prohibition or command that we should not receive or entertain any of those people called Quakers because they are supposed to be, by some, seducers of the people. For our part we cannot condemn them in this case, neither can we stretch out our hands against them, for out of Christ God is a consuming fire, and it is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.

Wee desire therefore in this case not to judge least we be judged, neither to condemn least we be condemned, but rather let every man stand or fall to his own Master. Wee are bounde by the law to do good unto all men, especially to those of the household of faith. And though for the present we seem to be unsensible for the law and the Law giver, yet when death and the Law assault us, if wee have our advocate to seeke, who shall plead for us in this case of conscience betwixt God and our own souls; the powers of this world can neither attach us, neither excuse us, for if God justifye who can condemn and if God condemn there is none can justifye.

And for those jealousies and suspicions which some have of them, that they are destructive unto Magistracy and Ministerye, that cannot bee, for the Magistrate hath his sword in his hand and the Minister hath the sword in his hand, as witnesse those two great examples, which all Magistrates and Ministers are to follow, Moses and Christ, whom God raised up maintained and defended against all enemies both of flesh and spirit; and therefore that of God will stand, and that which is of man will come to nothing. And as the Lord hath taught Moses or the civil power to give an outward liberty in the state, by the law written in his heart designed for the good of all, and can truly judge who is good, who is evil, who is true and who is false, and can pass definitive sentence of life or death against that man which arises up against the fundamental law of the States General; soe he hath made his ministers a savor of life unto life and a savor of death unto death.

The law of love, peace and liberty in the states extending to Jews, Turks and Egyptians, as they are considered sons of Adam, which is the glory of the outward state of Holland, soe love, peace and liberty, extending to all in Christ Jesus, condemns hatred, war and bondage. And because our Saviour sayeth it is impossible but that offences will come, but woe unto him by whom they cometh, our desire is not to offend one of his little ones, in whatsoever form, name or title hee appears in, whether Presbyterian, Independent, Baptist or Quaker, but shall be glad to see anything of God in any of them, desiring to doe unto all men as we desire all men should doe unto us, which is the true law both of Church and State; for our Saviour sayeth this is the law and the prophets. Therefore if any of these said persons come in love unto us, we cannot in conscience lay violent hands upon them, but give them free egresse and regresse unto our Town, and houses, as God shall persuade our consciences, for we are bounde by the law of God and man to doe good unto all men and evil to noe man. And this is according to the patent and charter of our Towne, given unto us in the name of the States General, which we are not willing to infringe, and violate, but shall houlde to our patent and shall remaine, your humble subjects, the inhabitants of Vlishing.

Written this 27th of December in the year 1657, by mee.

Edward Hart, Clericus

Tobias Feake

Nathaniell Tue

The marke of William Noble

Nicholas Blackford

William Thorne, Seignior

The marke of Micah Tue

The marke of William Thorne, Jr.

The marke of Philip Ud

Edward Tarne

Robert Field, senior

John Store

Robert Field, junior

Nathaniel Hefferd

Nich Colas Parsell

Benjamin Hubbard

Michael Milner

The marke of William Pidgion

Henry Townsend

The marke of George Clere

George Wright

Elias Doughtie

John Foard

Antonie Feild

Henry Semtell

Richard Stocton

Edward Hart

Edward Griffine

John Mastine

John Townesend

Edward Farrington

Sources

Russell Shorto. The Island at the Center of the World (2005)

Oliver A. Rink. Holland on the Hudson: An Economic and Social History of Dutch New York (1989)

Jaap Jacobs. The Colony of New Netherland: A Dutch Settlement in Seventeenth-century America (2009)

The Flushing Remonstrance, read by Henry Miller, Esq.From the 2009 Society program, Before New York, There was New Netherland: Our Dutch Heritage, 1609-2009 |