The Dooms of Ethelred (978-1016 A.D.)

The thirty-eight year reign of Ethelred II is the first for which we have contemporary manuscripts containing the text of the Dooms. The king issued two sets, one known as the Woodstock (or Anglo-Saxon Dooms) (V Æthelred) and the other as the Wantage Code (III Æthelred). Both were promulgated around 997.

The Anglo-Saxon Dooms (V Æthelred), possibly issued at a meeting of the royal council at Woodstock, continued the expansion of the Crown’s legal and fiscal rights with enactments relating to currency reform, “heregeld” (a tax on the population to support the war against the Danes), and other monetary provisions. The Dooms mandated that all fines payable to the king’s reeve (sheriff) must go directly to the king (in every burh, and in every shire, shall I have the dues of my kingship, as my father had).

Wulfstan, Archbishop of York, committed the Woodstock Dooms to writing for the memory of posterity, and the benefit of men, now and in the future. Bear in mind, however, the late Anglo-Saxon scholar Patrick Wormald’s caution that:the King’s Word had permanent significance but only within the limitations of any verbal communication: that is, absolute integrity was dependent upon memory, and was subject, as such, to adjustment, both conscious and subconscious. Written legislation was a useful aid to memory, and sometimes an impressive manifestation of the civilized status of its royal author, but it was not binding, like modern statute law.

The Wantage Code (III Æthelred) applied in the Danelaw, an area of England settled by the Danes (Vikings). The manuscript contains many Scandinavian terms and include penalties for breach of peace, regulations on the conduct of ordeals, arbitration and the punishment of condemned thieves. Some scholars believe this code contains the prototype for the jury of presentment but others, including Maitland, agree that although Ethelred’s twelve thegns (king’s followers) may have constituted the first instance of an accusing jury, no connection should be made to the twelfth-century jury of presentment constituted during the reign of Henry II.

Patrick Wormald summed up Ethelred’s reign as follows: though Aethelred’s secular laws do not represent anything strikingly original, they help to explain, by their continuity with what went before and came after, the fact that the Anglo-Saxons presented their Norman conquerors with a system of centrally directed legal administration which is unparalleled in eleventh century Europe, and which is a vital reason, if not the vital reason, why England still has a system of native common law rather than one of Roman civil law.

The Dooms of Cnut

Background

In 1013, an army of Vikings led by Sweyn conquered England and Ethelred fled to Normandy. Just a few months later, on February 3, 1014, Sweyn died and the English nobility then invited Ethelred to resume the throne of England, subject to certain conditions. At the same time, Sweyn’s son, Cnut, claimed his father’s kingdom but as he had not yet assembled an army, he was forced to withdraw from England. Shortly afterward, Edmund Ironside, Ethelred’s son, rebelled against his father and assumed the throne of the Danelaw. When Cnut returned to England with his army in August 1015, he quickly became the victor. Ethelred and Edmund joined forces to defend London but Ethelred died on April 23, 1016, and Cnut defeated Edmund at the Battle of Ashingdon on October 18, 1016. In the peace that followed, Edmund retained the Kingdom of Wessex and Cnut reigned over the all of the other lands. One month later, on November 30, 1016, Edmund died and Cnut became King of England. With the help of Archbishop Wulfstan, Cnut issued two sets of Dooms, the last issued in Anglo-Saxon England.

The Code of Cnut as recorded by Archbishop Wulfstan

Oxford Dooms, 1018 A.D.

These Dooms represent the agreement by the English and the Danes executed in Oxford in 1018 under which both peoples consented to be bound by the Anglo-Saxon laws prevailing during the reign of Edgar I.

Winchester Dooms c. 1020 A.D.

Issued at Winchester in 1020 or 1021, these Dooms constitute the most comprehensive record of Anglo-Saxon law. The code is chiefly a reiteration of the Dooms of Ethelred and Edgar. Eight manuscripts of the text still exist and among the provisions they contain are punishments for committing adultery, perjury and sorcery, measures for reforming the coinage, and provisions for repairing bridges and fortifications. Many of its clauses deal with murder which was punishable by outlawry or death. The code also specifies that “if anyone plots against the king or against his own lord, he shall forfeit his life and all that he possesses.” Archbishop Wulfstan again committed the Dooms to writing and his manuscript is in the collection of the British Library.

The Anglo-Scandinavian Empire

King Harald of Denmark died around 1018 and Cnut, as his brother’s heir, went to Denmark to claim the throne. Ten years later, Cnut led a fleet of 50 ships from England and Denmark along the Norwegian coast, receiving oaths of allegiance from the local chieftains along the way. He reached Nidaros at the time of the Eyrathing, and was t

here acclaimed king of his brother’s empire. The lands over which Cnut now reigned became known as the Anglo-Scandinavian Empire.

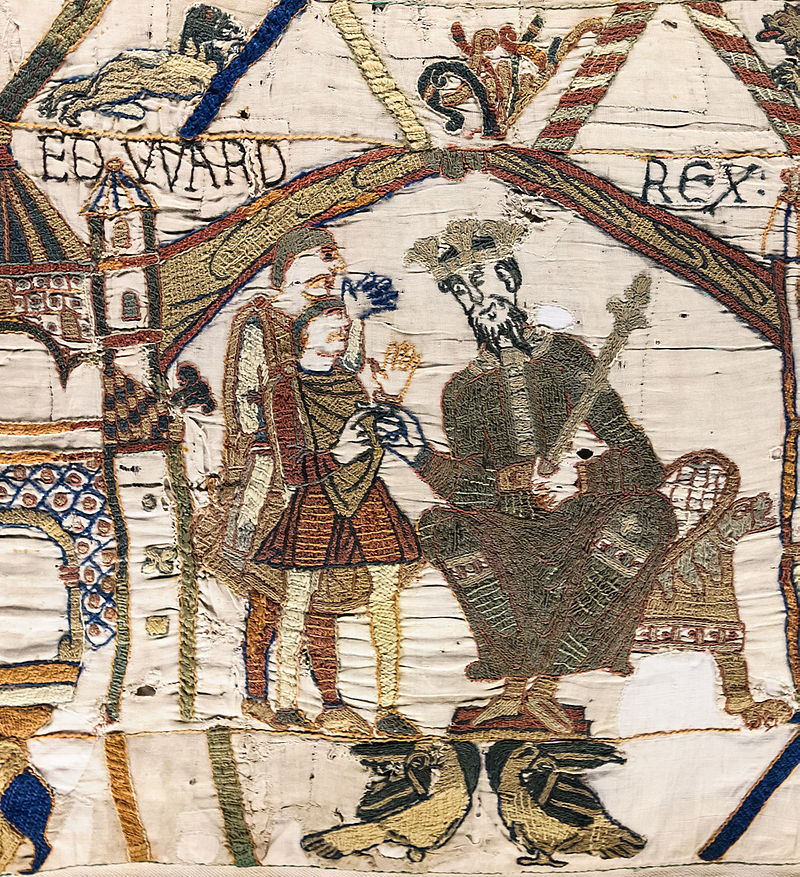

Laws of Edward the Confessor

Background

Edward was the son of Ethelred II and his second wife, Emma of Normandy. Following Ethelred’s death in 1016, Emma married Cnut. Upon Cnut’s death in 1035, his son, Harthacnut, ascended to the throne in Denmark and installed his half-brother, Harold, as Regent of England. In 1037, Harold, who at the time was attempting to claim the throne in his own name, died. Harthacnut, who had no living heirs, recalled his step-brother Edward from France to meet with “all the thegns of England.” On Harthacnut’s death in 1042, Edward was acclaimed King of England and reigned indifferently until his death in January, 1066, when Harold, Earl of Essex, was crowned the last king of Anglo-Saxon England.

William, Duke of Normandy, disputed Harold’s right to the English throne and pursued his claim by invading England in September, 1066. Two weeks later, on October 14, 1066, William defeated and killed Harold and his brothers at the Battle of Hastings.

Now known as William, the Conquerer, he became the first Norman King of England.

Leges Edwardi Confessoris (1042–1066)

This anonymous manuscript purports to be a collection of the laws issued during the reign of Edward the Confessor. The preface recounts that four years after the Conquest, King William summoned twelve learned English noblemen from the shires to declare, under oath, the laws and customs of the nation in the time of Edward the Confessor. There is no historical support for this meeting and Pollock and Maitland state that It is private work of a bad and untrustworthy kind. It has about it something of the political pamphlet and is adorned with pious legends. However, the work’s most recent commentator, Bruce O’Brien, argues that it offers apparently original observations of and comments on the English law of the author’s day.

Sources

Patrick Wormald. Æthelred the Lawmaker in Hill, David (ed.), Ethelred the Unready: papers from the millenary conference (1978).

Dorothy Whitelock English Historical Documents, 500-1042 (1996)

F. Pollock & F.W. Maitland. The History of English Law before the Time of Edward I (1898).

University of London, Institute of Historical Research. Early English Laws Project. http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/i-atr/ http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/iii-atr/ http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/cn-1018/ http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/ecf1/ http://www.earlyenglishlaws.ac.uk/laws/texts/ecf2/

Bruce R. O’Brien. God’s Peace and King’s Peace: The Laws of Edward the Confessor (1999)