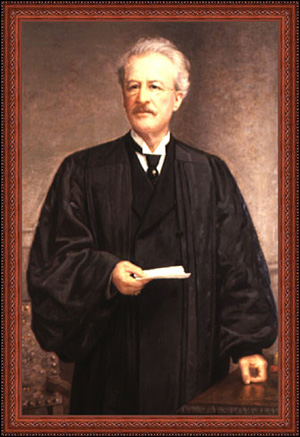

“The law of truth was in his mouth, and unrighteousness was not found in his lips,”1 so said the Court of Judge Vann on June 7, 1921, honoring him on his passing. Irving G. Vann was born on his parents’ farm at Willow Creek in the town of Ulysses, Tompkins County, New York on January 3, 1842. His great-grandfather on his father’s side, Samuel Vann, had been a lieutenant in the Revolutionary War. His grandfather on his mother’s side, Joseph Goodwin, fought in the War of 1812. He was the only child of his parents, Samuel R. Vann and Catherine H. Goodwin Vann, and spent much of his early life on the family farm under the tutelage of his mother.

Irving Vann received no formal education until he began to attend the Trumansburg Academy in preparation for college. The Academy was located some four miles from the Vann farm and, during the warmer months, Irving walked the distance to and from school unless his father was able to spare a horse from the work of the farm. During the winter, Vann boarded at Trumansburg. He also spent a year of study at Ithaca Academy, which enabled him to enroll at Yale College in 1859. After struggling his first year to catch up with his more formally-schooled classmates, Vann graduated with his class in 1863.

Initially pursuing a career in education, Vann became a high school principal and teacher in Owensboro, Kentucky. Although his employers urged him to continue in that field, he resigned after a year and began to study law at the office of Boardman & Finch in Ithaca, New York. In the fall of 1864, he entered Albany Law School, graduating in the spring of 1865. Although he never returned to a full-time teaching career, later in life Vann shared his knowledge with students, lecturing at Syracuse, Albany, and Cornell law schools.

Upon his graduation, Irving Vann accepted a position at the Department of Treasury in Washington, D.C. In less than a year, however, he returned home to Central New York, joining the law firm of Raynor & Butler in Syracuse. This began an illustrious career in private practice there, with a succession of law firms bearing his name: Vann & Fiske, Raynor & Vann, Fuller & Vann, and Vann, McLennan & Dillaye. Irving Vann became an accomplished appellate lawyer and also served as a referee until his practice prospered to such an extent that it demanded his full attention.

As a lawyer at the bar he was particularly strong as a counselor and advocate. He knew the law and understood the principles. He had a large clientage and his reputation extended far through the State.2

His career well established, Vann married (Julie) Florence Dillaye, the daughter of a prominent Syracuse real estate developer, on October 11, 1870. The couple produced two children: a daughter Florence and a son Irving. Vann was an active member of the Syracuse legal community and was one of the founders of the New York State Bar Association and served as an early president of the Onondaga Bar Association. Judge Vann was president of a number of civic and philanthropic organizations, including the Woodlawn Cemetery Board and the Onondaga Red Cross Society, and was a member of many others, including the New York State Historical Society and the Albany Historical Society. He founded the Onondaga Country Club and was its first president in 1898, and was active in a number of social organizations, including the Century Club, the Fort Orange Club, and the University Club.

A member of the liberal wing of the Republican party, Irving Vann also participated extensively in local political affairs.

He actively engaged in several political campaigns but was not a candidate for office until 1879, when he was unanimously nominated as the Republican candidate for mayor of Syracuse. With three candidates in the field he was elected by a majority of more than a thousand. His administration as mayor was characterized by the lowest taxes that the city had known for many years. Declining a renomination he again took up the practice of his profession.3

Vann’s return to work in the private sector after the completion of a one-year term as Syracuse mayor was short-lived. In 1881, his party nominated him to run for Justice of the Supreme Court in the Fifth Judicial District. He handily defeated his opponent, winning by a margin of over 11,000 votes. Justice Vann served on the Supreme Court trial bench until 1889 when he began the first of his two associations with the Court of Appeals. When a Second Division of the Court of Appeals was created in 1889 to address the Court’s overwhelming case load, Vann was one of seven Supreme Court Justices from throughout the state who were appointed to decide appeals sitting as a separate body from the original Court.4 Justice Vann served on the Second Division until it was dissolved in 1892, then he returned to the trial bench.

At the conclusion of his first term on Supreme Court in 1895, Justice Vann was endorsed by both parties to run for reelection. As a New York Times journalist explained:

That Justice Vann will succeed himself is beyond the question of a doubt. No more popular Judge sits upon the bench in the district, and he is equally in the favor of both clans. He took the bench Jan. 1, 1882 and, although he has served his fourteen years, he is now but fifty-five years old. He is counted one of the most active and industrious Judges in the Supreme Court of the State, and has never absented himself from his post or duty, either by sickness or long vacation . . . He is a man of absolute and unquestioned fairness, and the satisfaction he has given is evidenced by the great readiness shown by his party to give him the renomination. So far no Democrat has come forward as a candidate for the nomination.5

In fact, no opponent materialized and Justice Vann was unanimously returned to the Supreme Court bench.

Within days of the election, Justice Vann having already proven himself an able appellate jurist, Governor Levi Morton immediately considered nominating him to the newly-created Supreme Court, Appellate Division. Concerned that such an appointment “would be to the detriment of his Circuit” due to the volume of trial work in Syracuse, Justice Vann persuaded the Governor against it.6 However, the next year Governor Morton succeeded in appointing him to the Court of Appeals, filling the vacancy created when Judge Rufus W. Peckham Jr. was elevated to the United States Supreme Court.7 Since a Court of Appeals judgeship was then an elected position, Judge Vann soon found himself running in a statewide election. He again proved his strength as a candidate, winning by a majority of 243,180, which at that time was the largest majority ever achieved by a state officer in a contested election. On the bench, Judge Vann:

showed a vigorous and keen intellect, a mind well stored with law and a sharp sense for the equity of the case before him. His grasp of the merits and the facts [was] comprehensive. He [was] above prejudice, he was never biased by friendship or personal dislike, and he could not be deceived by the sophistry of ‘bluffing’ lawyers.8

Upon the completion of his 14-year term, Judge Vann was nominated by both parties and succeeded at being reelected to a second term in the fall of 1910. He served on the Court of Appeals until January 1, 1913, when he reached the mandatory retirement age of 70. Following his retirement, Judge Vann continued to serve the people of New York State as the Official Referee appointed to hear claims arising out of the construction of the Barge canal.

During his tenure on the Court of Appeals, Judge Vann authored a number of significant opinions. Perhaps the most well known is In Re Totten (179 NY 112 [1904]), in which the Court articulated the common law rules applicable to what has come to be known as a “Totten Trust.” In simple terms no less relevant today than they were when published more than a century ago, Judge Vann explained:

A deposit by one person of his own money in his own name as trustee for another, standing alone, does not establish an irrevocable trust during the lifetime of the depositor. It is a tentative trust merely, revocable at will, until the depositor dies or completes the gift in his lifetime by some unequivocal act or declaration . . . In case the depositor dies before the beneficiary without revocation, or some decisive act or declaration of disaffirmance, the presumption arises that an absolute trust was created as to the balance on hand at the death of the depositor (179 NY at 125).

This cogent statement remains black letter law, Judge Vann’s opinion having been cited by the Court of Appeals as recently as 2003 (see Eredics v. Chase Manhattan Bank, N.A., 100 NY2d 106, 110 [2003]). Equally significant, though less known, was his decision in Tabor v. Hoffman (118 NY 30 [1889]), where “Vann articulated fundamental principles that have since governed trade secret law, i.e., distinguishing between the free imitation of a competitor’s product and the stealing of product secrets through bribery or other wrongdoing.”9

But the opinion that best displays Judge Vann’s personality and literary skill is Smith v. United States Casualty Co. (197 NY 420 [1910]) in which the Court held that, under the common law, a person has the right to change his or her name at will as long as the alteration is done in good faith and for an honest purpose. In reaching that conclusion, Judge Vann lyrically cited notable historical figures who adopted new names:

The history of literature and art furnishes many examples of men who abandoned the name of their youth and chose the one made illustrious by their writings or paintings. Melanchthon’s family name was Schwartzerde, meaning black-earth, but as soon as his literary talents developed and he began to forecast his future he changed it to the classical synonym by which he is known to history.

Rembrandt’s father had the surname Gerretz, but the son, when his tastes broadened and his hand gained in cunning, changed it to Van Ryn on account of its greater dignity.

A predecessor of Honore de Balzac was born a Guez, which means beggar, and grew to manhood under that surname. When he became conscious of his powers as a writer he did not wish his works to be published under that humble name, so he selected the surname Balzac from an estate that he owned. He made the name famous, and the later Balzac made it immortal.

Voltaire, Moliere, Dante, Petrarch, Richelieu, Loyola, Erasmus and Linnaeus were assumed names. Napoleon Bonaparte changed his name after his amazing victories had lured him toward a crown and he wanted a grander name to aid his daring aspirations. The Duke of Wellington was not by blood a Wellesley but a Colley, his grandfather, Richard Colley, having assumed the name of a relative named Wesley, which was afterward expanded to Wellesley”(197 NY at 425).

The extensive knowledge of history, art, and literature that Judge Vann displayed in Smith reflected his love of books. His home library contained “more than 10,000 volumes, many of which were rare.”10 During his lifetime, he was described as

a most charming man. His culture is broad and thorough and he can discuss with authority most of the questions of the day and many of the scientific and historical topics. His library is one of the finest. He is a genial companion, fond of outdoor sports, and it has been said of him that he has not an enemy in the world.11

In addition to his intellectual pursuits, Judge Vann spent much of his leisure time outdoors. He had a home in Cranberry Lake, St. Lawrence County, which the family still enjoys, including a portrait of the Judge. He also owned property near Baldwinsville, overlooking the Seneca River, described as “one of the ideal spots in Central New York”12 He collected antique firearms and was known as an avid sportsman until advancing years and ill health limited his activity. That he had lost none of his literary deftness was evident when, in 1913, he addressed the University Club in Albany. In a speech entitled Yale Fifty Years Ago, Vann described life as a student in New Haven from 1859-1863. He gave the talk at the end of 1912 — on the last day of his life on the Court — “before becoming disqualified by constitutional softening of the brain,” he said. Judge Vann’s delivery carried the grace of a consummate after dinner speaker. With self-effacing humor, he gave a hilarious account dealing with his Greek textbook in the college’s entrance exam. Next came the travails of a freshman, before he “reached the pride, pomp and dignity of a sophomore.” His witty reminiscences painted a lifelike picture of his years at college and are a joy to read. Beyond that, any reader would want to know this charming and erudite man.

Judge Vann died at his home in Syracuse on March 22, 1921, surrounded by his family. He was 79 years old. Upon his death, his colleagues on the bench wrote of him:

His fame rests not on the keen perception of narrow technicalities, but rather on the ability to grasp the body of the law as a whole. When some new phase of legislative action was under consideration his vision was turned not only to a past which knew not such things, but also to the future and to those necessary readjustments of the social structure which the law is at times prone to welcome only after they have become commonplaces outside courts of justice . . . Of the judges who sat in this court with him but two remain on the Bench, yet by tradition or personal contact we all knew him as one of simple life who had dedicated his rare talents to the public service in the administration of justice rather than to the pursuit of gain in the cause of litigants.13

Progeny

Judge Vann was survived by his wife Florence (1846-1934) and their two children. Their son, Irving Dillaye Vann (1875-1944), never married but followed in his father’s footsteps, graduating from Yale University. He went to Harvard Law School and became a prominent Syracuse attorney.14 Judge Vann’s daughter Florence (1871-1942) married Albert Perry Fowler (1867-1915), also of Syracuse, in 1899 and had four children who grew to adulthood: Katherine Dillaye Fowler (1902-1956), Albert Vann Fowler, (1904-1968) and twin daughters Elizabeth Fowler (1907-1952) and Ruth Fowler (1907-1982). Another, Florence Janette (1900-1900) died in infancy.

Albert Vann Fowler, who apparently inherited his grandfather’s love of books, married a poet, Helen Frances Wose (1907-1968). He and his wife were noted in the literary world as poets, freelance writers, and managing editors of a literary periodical called Approach. They had one child, Albert Wose Fowler (1940- ), a librarian and archivist. He married Anna Smith (1956- ), and they have a son, Benjamin (1992- ).

Katherine Dillaye Fowler married Henry Wilkinson Bragdon (1906-1980). They had two sons, David May Bragdon (1932-1998) and Peter Wilkinson Bragdon (1936- ). Peter married Dorothy Davison (1938- ), and they have three children: William Vann Bragdon (1961- ) of Rosemont, Pennsylvania; Christopher Fowler Bragdon (1963- ) of Brookline, Massachusetts; and Katherine Dillaye Bragdon (1968- ) of Seattle, Washington. William Van Bragdon has three children: Jacob Chandler Bragdon (1996- ), Katherine Zaradic Bragdon (2001- ), and Peter Joseph Bragdon (2005- ).

Of the twin daughters Elizabeth and Ruth Fowler, Elizabeth married Chandler May Bragdon, (1907-1969), and they had one son, Samuel Dillaye Bragdon (1943-1983). Ruth married Richard McFall Martin (1911-1957), and they had three children, Christopher Bruce Martin (1940- ), Sheila Martin Mackintosh (1946- ), and Julie Martin (1948- ).

This biography appears in The Judges of the New York Court of Appeals: A Biographical History, ed. Hon. Albert M. Rosenblatt (New York: Fordham University Press, 2007). It has not been updated since publication.

Sources Consulted

Anxious To Be Justice, New York Times, New York, New York, September 5, 1895, includes a sketch of Justice Vann.

Bonventre, Albany Law School On The High Court, 64 Alb. L. Rev. 1155 (2001).

Diaries of Judge Vann, in possession of family historian Sheila Mackintosh of Little Compton, Rhode Island.

Eminent Members of the Bench and Bar of New York, at 171 (C. W. Taylor, Jr. 1943).

Ex-Judge I. G. Vann Dead, New York Times, New York, New York, March 23, 1921.

Funeral of Judge Vann To Be Held Tomorrow, The Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York, March 23, 1921.

In Memoriam, 230 NY 663, 664 (1921).

Irving D. Vann, 68, Syracuse Lawyer, New York Times, New York, New York, August 8, 1944.

Irving Goodwin Vann, Syracuse Herald, Syracuse, New York, August 29, 1900.

Judge Irving G. Vann, Distinguished Citizen, Dies in His 80th Year, Syracuse Herald, Syracuse, New York, March 22, 1921.

Judicial Appointments Made, New York Times, New York, New York, January 1, 1896.

Justice Vann Takes the Oath, New York Times, New York, New York, January 8, 1896.

Kellogg A County Judge, New York Times, New York, New York, November 14, 1895.

Letter from Albert Vann Fowler to Theodore Irving Vann dated August 19, 1962.

Letter from Judge Irving G. Vann to Livingston Vann dated January 23, 1918.

Letter from Judge Irving G. Vann to Preston S. Vann dated October 24, 1913.

Mrs. I. G. Vann Dead, Widow of Bench Leader, The Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York, January 20, 1934.

Seven Fortunate Judges, New York Times, New York, New York, January 17, 1889.

Spencer, Judge Irving G. Vann, 22 Green Bag 11 (1910).

Strong, Landmarks of a Lawyer’s Lifetime, at 42 (Dodd, Mead & Co. 1914).

The New Supreme Court, New York Times, New York, New York, November 16, 1895.

The Notable Men of Syracuse, The Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York, June 9, 1901.

To Dine Retiring Judges, New York Times, New York, New York, December 6, 1912.

Published Writings Include

Irving G. Vann, Contingent Fees: Address in Hubbard Course on Legal Ethics Delivered at Commencement of Albany Law School (1905).

Endnotes

- In Memoriam, 230 NY 663, 664 (1921).

- The Notable Men of Syracuse, The Post-Standard, Syracuse, New York, June 9, 1901.

- Judge Irving G. Vann, Distinguished Citizen, Dies in His 80th Year, Syracuse Herald, Syracuse, New York, March 22, 1921.

- Seven Fortunate Judges, New York Times, New York, New York, January 17, 1889.

- Anxious To Be Justice, New York Times, New York, New York, September 5, 1895, includes sketch of Justice Vann.

- The New Supreme Court, New York Times, New York, New York, November 16, 1895; Kellogg A County Judge, New York Times, New York, New York, November 14, 1895.

- Judicial Appointments Made, New York Times, New York, New York, January 1, 1896; Justice Vann Takes the Oath, New York Times, New York, New York, January 8, 1896.

- The Notable Men of Syracuse, supra n 2.

- Bonventre, Albany Law School On The High Court, 64 Alb. L. Rev. 1155 (2001).

- Judge Irving G. Vann, Distinguished Citizen, Dies in His 80th Year, supra n3; see also, the Irving Goodwin Vann Collection, 1778-1887, at the Yale University Library, Manuscripts and Archives. Other records of Judge Vann include Irving G. Vann Papers, 1865-1914 (nine volumes of scrapbooks and papers at the Onondaga Historical Association in Syracuse) and New York State Literary Manuscript Division, Papers, 1882-1928 (one box of documents including correspondence concerning the defense of New York State Governor William Sulzer).

- The Notable Men of Syracuse, supra n 2.

- Judge Irving G. Vann, Distinguished Citizen, Dies in His 80th Year, supra n 3.

- In Memoriam, supra n 1, 230 NY at 664.

- Irving D. Vann, 68, Syracuse Lawyer, New York Times, New York, New York, August 8, 1944.