Amendment I of the United States Constitution

Congress shall make no law respecting an establishment of religion, or prohibiting the free exercise thereof; or abridging the freedom of speech, or of the press; or the right of the people peaceably to assemble, and to petition the Government for a redress of grievances.

Ratified December 15, 1791

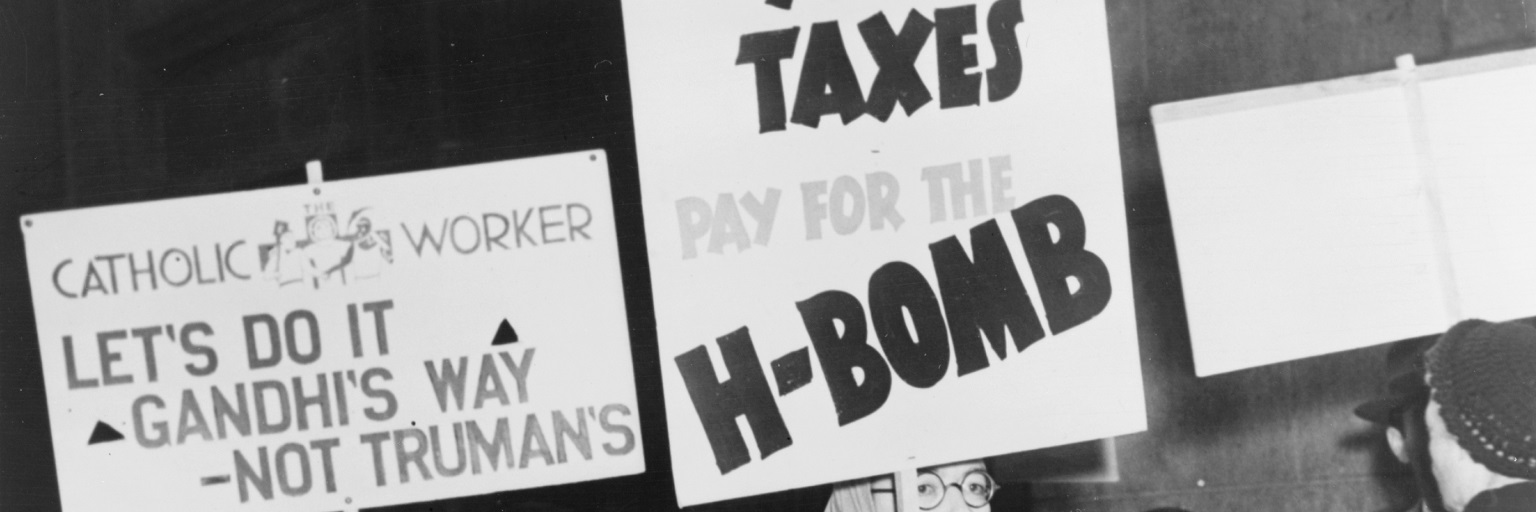

Freedom of Assembly/Right to Petition are Essential to Democracy

Freedom of assembly/right to petition are focused on public participation and communication, where people are free to gather and associate with each other, engage in expressive activities, and communicate directly with their representatives.

The First Amendment is a restriction on governmental action, “Congress shall make no law … abridging … the right of the people to peaceably assemble.” Thus, for First Amendment protections, state action is required, a federal restriction on assembly or state restriction on assembly (in De Jonge v. Oregon (1937), the Supreme Court incorporated freedom of assembly in the First Amendment to apply to the states through the 14th Amendment).

The Supreme Court has held that people may assemble on public property, including a traditional “public forum” such as a park, as well as public streets and sidewalks to express themselves and can petition their government through assembly or through written petitions mailed or sent electronically. Reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on assembly are permissible, but they must be content/viewpoint-neutral and should be narrowly tailored to serve a legitimate government interest.

Is Social Media a Public Forum?

Social media is not a public forum and the First Amendment does not apply to social media because it is privately owned and controlled, and there is no state action. However, as speech, expression, and petition have shifted to social media, it raises questions on whether the definition of a public forum should be revised and whether there should be federal regulation.

Furthermore, social media can be transformed into a public forum through governmental action and the First Amendment protections will apply. In Knight First Amendment Institute v. Trump (2019), the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Second Circuit held that President Trump had used his Twitter account to conduct official governmental business in an official capacity, and therefore had transformed his account into a “public forum,” such that under the First Amendment’s freedom of assembly and right to petition, he could not block Twitter followers, as that would constitute governmental action and would be unconstitutional as a content/viewpoint-based restriction on speech.

Hague v. Committee for Industrial Organization (1939)

The Supreme Court invalidated a city ordinance banning individuals from meeting in a public place to discuss labor organizing and rights afforded to them under the National Labor Relations Act without a permit. Declaring that such a restriction on the right of assembly was unconstitutional under the First Amendment and an abridgement of the “privileges” of citizenship under the Fourteenth Amendment, the Court held that “Wherever the title of streets and parks may rest, they have immemorially been held in trust for the use of the public and, time out of mind, have been used for purposes of assembly, communicating thoughts between citizens, and discussing public questions. Such use of the streets and public places has, from ancient times, been a part of the privileges, immunities, rights, and liberties of citizens.” The Court continued, “The privilege of a citizen of the United States to use the streets and parks for communication of views on national questions may be regulated in the interest of all; it is not absolute, but relative, and must be exercised in subordination to the general comfort and convenience, and in consonance with peace and good order; but it must not, in the guise of regulation, be abridged or denied.” Learn More

Ward v. Rock Against Racism (1989)

The Supreme Court held that reasonable time, place, and manner restrictions on traditional public forum assemblies are constitutional under the First Amendment, if those restrictions are content-neutral and are narrowly tailored to serve the government’s legitimate interests. Yet, the restrictions “need not be the least restrictive or least intrusive means” of serving those interests. Learn More

- Expansion, Nationalism, and Sectionalism (1800-1865): 11.3 (b)

- Cold War (1945-1990): 11.9 (a)

- Social and Economic Change/Domestic Issues (1945-Present): 11.10 (a), 11.10 (b)

- Foundations of American Democracy: 12.G1 (f)

- Civil Rights and Civil Liberties: 12.G2 (a), 12.G2 (b), 12.G2 (c)

- Rights, Responsibilities, and Duties of Citizenship: 12.G3 (a)

- Political and Civic Participation: 12.G4 (c), 12.G4 (e)

- “Interpretation & Debate: Right to Assembly and Petition,” posted by the National Constitution Center

- Resources for Freedom of Assembly and Freedom of Petition, posted by the Bill of Rights Institute

- First Amendment Fundamental Freedoms, in Constitution Annotated, produced by the Congressional Research Service

“Why Are the Rights to Assembly and Petition Important to Liberty?” includes activities and handouts, posted by the Bill of Rights Institute

Freedom of Assembly: National Socialist Party v. Skokie, from the Annenberg Classroom. This video discusses the First Amendment right of assembly and examines the Supreme Court decision in National Socialist Party of America v. Village of Skokie (1977), concerning neo-Nazis planning to march in a predominantly Jewish community. Here is a lesson plan to accompany this video.

“John Quincy Adams and His Struggle Against Slavery and the Gag Rule,” includes background information handout and discussion questions, posted by the Bill of Rights Institute