The Depression-Era Murals of the

New York County Courthouse

by Robert C. Meade, Jr., Esq.[*]

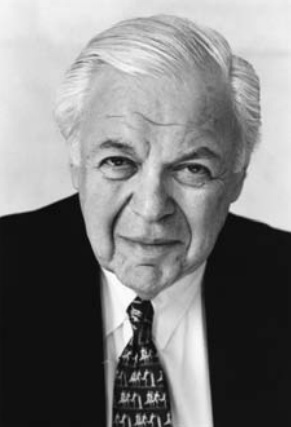

This article is dedicated to the memory of the Honorable Norman Goodman, the very-long serving County Clerk of New York County and a devoted guardian of the New York County Courthouse.

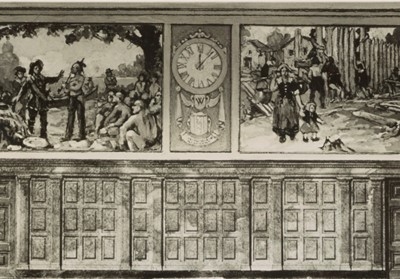

The murals of the New York County Courthouse, of which there are 38, have, since their creation during the Great Depression, been widely recognized as treasures, among the outstanding works of such art in the great metropolis of New York, the country’s principal center of artistic life and work. In 1981, the Landmarks Preservation Commission of the City of New York designated as landmarks the “excellent” and “powerful” murals of the first two floors of the County Courthouse.[1] And when a painter, muralist, and scholar of art collected images of and wrote about the leading examples of mural art in New York City, namely, the 33 most important, influential, and impressive murals in the city, the murals of 60 Centre Street received a chapter, as they certainly deserved.[2] The great murals at the New York County Courthouse, like those elsewhere in New York City, “say to those who inspect them that they too are part of this magnificent continuum of human endeavor and achievement that is New York.”[3]

What follows is the story of the murals. This story has multiple dimensions, and some of these extend beyond the history and artistic programs of the physical paintings themselves. These dimensions shed some light on important aspects of America in the 20th century. They tell us something about hard work, effort, and inspiration: the struggle of the immigrant to make his way in a foreign culture in which many, perhaps the majority, speak a language different from his own and of the sacrifices the journey to this country required; the effort of artists to carve out for themselves a career that is successful artistically, but that is also financially realistic in a commercially-driven country; and the never-ending struggle to bring beauty to public life. One dimension of the story concerns the seriousness of the challenges that faced so many ordinary people during the tremendous economic catastrophe that was the Great Depression, the worst in the history of the country, and the efforts of the government to help artists, like other workers, to survive and maintain their skills, while enriching national life by bringing art to the American people. This story, being centered around the work of one of the country’s most important and widely-recognized courthouses, also gives us reason to think about the struggle to honor, but also to bring to reality for everyone, the ideals of justice and fairness in a system of ordered liberty under law. Finally, the story underscores the duty that falls on all of us to respect and preserve for future generations the artistic heritage of this country, which has so often been created by artists at great personal cost.

I. The Murals of the First and Second Floors

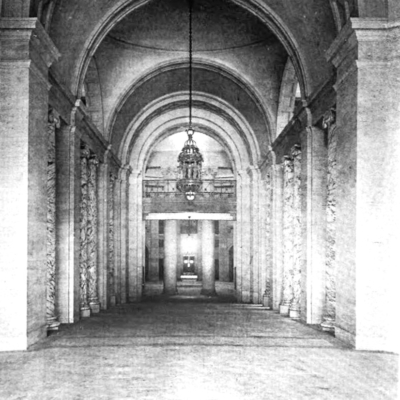

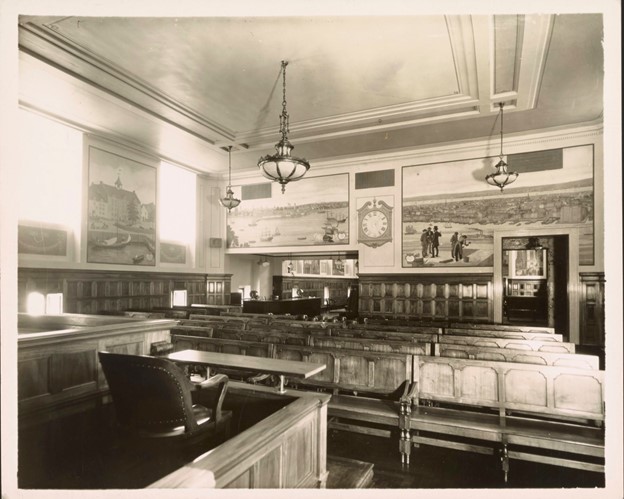

There are, as I said, 38 murals at the New York County Courthouse. (See the appendix for a listing.). This figure does not take into account the decorative (as opposed to mainly representational) murals on the first and second floors and in some other locations on upper floors. There are five representational murals on the first and second floors: the three-domed painting on the ceiling of the vestibule; the paintings over the two hallway passages in the vestibule; the painting on the ceiling of the main corridor; and the painting on the ceiling of the rotunda. There is also a substantial mural over the entrance to Courtroom 130. All of the mural paintings on the first and second floors are frescoes, which I will explain later. All but three of the 32 paintings on the upper floors are oils painted on canvas. The main representational murals on the first floor and in the rotunda are ceiling paintings, although there are three wall paintings on the first floor as well. The decorative paintings in the corridors on the first and second floors are on their walls and ceilings. All of the murals on the upper floors, on the other hand, are wall paintings. The principal paintings on the first floor and in the rotunda are by far the largest in the building.

I will first discuss the history of the murals on the first and second floors, their principal creator, and their artistic programs (i.e., their subjects). Thereafter, I will address the history of the murals on the upper floors, the identities and backgrounds of their creators, and the artistic programs of these paintings. Later, I will describe what I call missing murals and some other matters.

Images of some of the murals appear in this article. The reader can obtain a full view of any individual image in the article by clicking on it. Many other images of the murals can be found in the Photo Gallery that accompanies this article and the reader is urged to examine them

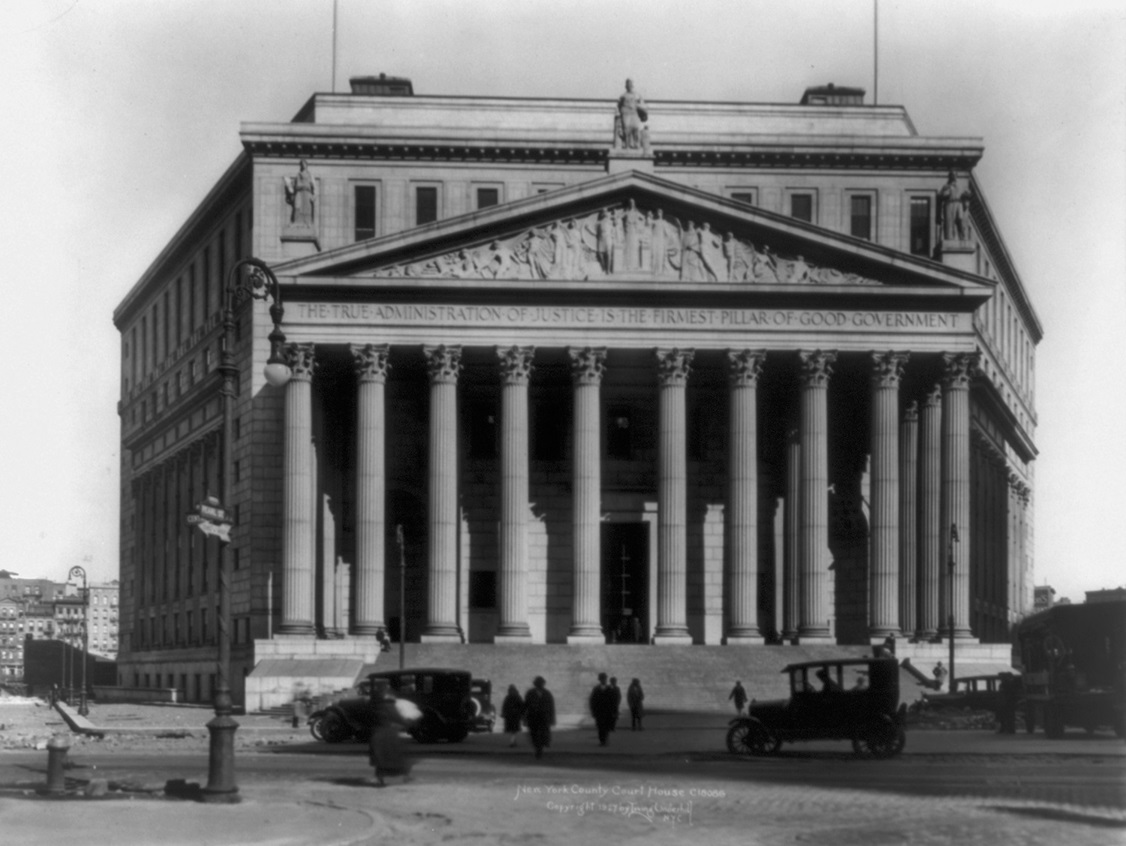

A. The Architect’s Plan

The New York County Courthouse was the work of Guy Lowell, “the quintessential gentleman architect of the American Renaissance,”[4] a scion of one of the most prominent Boston families, who was also well-known as a landscape architect. He designed and built the edifice over a very lengthy period. My colleague, John F. Werner, Esq., and I recount the history of the design and construction of this neo-Classical masterpiece and other aspects of the building in an article for the Historical Society of the New York Courts and I refer readers who may be interested in the architecture of the building and its history to that work.[5] One of the significant aspects of Lowell’s design was that there were to be decorations on walls and ceilings in portions of the new building. He planned that various spaces in the facility would be adorned with murals, above all in the rotunda of the main hall around which the building is centered and its life in many ways revolves. This plan was not a vague goal or general abstraction. It advanced to the point that he selected a muralist for the project he envisioned. This was Attilio Pusterla, whose background, life and work as a painter I will describe later in this article. In the end, Mr. Pusterla created the principal murals and oversaw the entire project of decoration, but that project did not proceed as rapidly as Lowell had no doubt hoped, as fate intervened.

During Guy Lowell’s work on the courthouse, he called upon Pusterla to make drawings for the murals that he planned for his new edifice. Pusterla did this and submitted the drawings and models to Lowell.[6] As best I can determine, Lowell was satisfied with Pusterla’s designs. I do not know, however, how much of the courthouse Lowell’s plans embraced, whether all of the walls and ceilings that were ultimately painted on were included in these designs, nor whether Lowell intended that murals be painted in additional sites in the building, including in the four locations for which murals were later formally proposed, and in one instance approved, but where none was ever executed. The murals were not, however, created before the dedication of the courthouse, which took place in February 1927. It may be that court authorities were anxious that the building be opened for court operations as soon as possible and that therefore other work on the project was given priority. The birth of the courthouse had after all been a troubled and an extraordinarily protracted process — a gestation of 14 years. A design competition for the project had been held in 1913 and progress on the project had been delayed by World War I, during which the site of the courthouse had been the location of a military facility. The war also had brought about fiscal problems for New York City that caused Lowell’s original design for a mammoth circular courthouse to be discarded and the project to be re-designed so as to be less costly.[7]

After the courthouse was dedicated, work on the murals still did not commence promptly. It ought to have been possible to proceed with the creation of the murals while the courthouse was in operation, as this in fact came to pass when the project was put into action later. It seems to me that the untimely death of Lowell just days before the dedication ceremony probably interfered with the work contemplated. But that would not provide an explanation for why the work still did not proceed for years thereafter, which is what transpired. Mr. Pusterla’s drawings and models remained with Major John H. House Jr., an architect who was an associate of Lowell,[8] who could have overseen the implementation of Lowell’s decorative ideas by Mr. Pusterla. From the length of the delay, the fact that the Great Depression began a little over two years after the dedication, and the fact that in the end the project began to come to life when a specific funding source became available, I deduce that it was funding challenges that principally brought about this delay.[9]

Thus, despite the intentions of the architect, when the courthouse opened in February 1927, its ceilings and walls were entirely devoid of decoration and it would be years, in the case of the ceiling of the main hall about a decade, before the murals were created.

What changed the status of the plans for the murals was that, after the economic disaster had descended upon the country, the government responded to the crisis with a variety of interventions, including a group of government-supported arts programs. Two of these programs made all the difference to the planned murals. Indeed, it is certainly possible that had these programs never been created, all the walls and ceilings of the courthouse would remain blank to this day.

B. The New Deal Art Programs

The funding that was to prove to be determinative for the creation of the murals came from federal art programs that were sponsored by the government under the Works Progress Administration (“WPA”) and other governmental bodies. These programs were created to address the unqualified disaster that befell the artistic community in America when the Depression began. One scholar describes succinctly what life became for artists during this terrible time:

The Depression had struck hardest at the American artist. His usual sources of income were destroyed and the market for what he could produce disappeared. As a result, he was forced to take whatever employment he could find or to go on the “dole.” The first option diminished his creative skills; the second, his self-esteem. [10]

There was at the time and remains today a marked tendency to think and speak of “the WPA art projects,” but that phrase is inaccurate. There were in fact four federal art programs that existed at various times between late 1933 and spring 1943, only one of which was administered under the WPA. These programs were known as – and here we must dip our spoon into the New Deal’s alphabet soup – (1) the Public Works of Art Project (1933-1934)(“the PWAP”); (2) the Treasury Department’s Section of Fine Arts (earlier known under the name of the Section of Painting and Sculpture)(1934-1943); (3) the Treasury Department’s Treasury Relief Art Project (1935-1939)(“the TRAP”); and (4) the Federal Art Project of the WPA (1935-1943). The four art programs assisted artists nationwide under somewhat varying rules and were funded in several ways. All of the art programs sought to assist artists financially at a time of economic crisis while bringing art to the public in public buildings across the country and in other ways, such as, in the case of the Federal Art Project, easel painting, posters, galleries, and art education. All of the programs sought to provide a wage or what I might call a relief wage to artists who met the requirements of the programs in return for the artists’ professional labors. These artists worked on art projects approved and supervised by the art programs. The largest of the art programs was the Federal Art Project of the WPA. The work on the murals at the New York County Courthouse was initially sponsored and the wages of the artists who carried out this work were paid by the Public Works of Art Project and thereafter by the Federal Art Project of the WPA.[11]

The Public Works of Art Project

The Public Works of Art Project, the PWAP, was set up within the Treasury Department in the early days of the Roosevelt Administration, with funds provided by the Civil Works Administration. In May 1933, painter George Biddle wrote to President Roosevelt, a close personal friend and former fellow student at Groton, to urge government support for mural art. This appears to have planted a seed.[12] (Later, in 1936, Biddle was to paint perhaps his greatest work, the fresco “Society Freed Through Justice,” on the fifth floor of the Justice Department Building in Washington with the sponsorship of the Section of Fine Arts of the Treasury Department. It no doubt did not hurt his ability to receive this assignment that he knew President Roosevelt so well. The social standing and connections of the Biddle family were substantial: George was also the brother of Francis Biddle, Attorney General of the United States for a number of years under Roosevelt. An ancestor, Nicholas Biddle, had been the President of the Bank of the United States and, in that role, an antagonist of President Andrew Jackson.)

Months after Biddle sent his letter, the PWAP was established. It began and moved ahead under the leadership of Edward Bruce, a remarkable man. He was a Columbia Law School graduate and practicing lawyer and businessman who, at age 44, had given up his business activities to become an artist, at which he had worked with some success for almost ten years. The inaugural meeting was held at Bruce’s house in December 1933, which was attended by museum directors and other leading figures in the art world from around the country, as well as Mrs. Roosevelt. The purpose of the PWAP was to provide support for artists to create public works of art in an effort to reduce unemployment and to benefit public spaces in the process.[13]

When the Civil Works Administration announced the availability of funds for the employment of artists through the PWAP to create public works of art, New York City naturally became a locus of interest since the City was, as it still is today, the art capital of America. New York City remained prominent in the Federal arts programs throughout their lives. In late 1937, for instance, New York employed through the Federal Art Project 44.5 % of all artists participating in that program.[14] Mrs. Juliana Force, the director of the Whitney Museum of American Art, was chosen as the regional chair of the PWAP.

The administration of the project in New York witnessed some controversies, which arose elsewhere as well. Forbes Watson, the technical director of PWAP, expressed at its outset its ambition to allow the artist “complete freedom,” without its procedures constraining the artist’s imagination to academicism on the one hand or radicalism on the other.[15] But this expression of intent did not carry the day in every region in every case. This should have surprised no one since art is, and throughout its history has been, often controversial, and the sensitivity of the public about the aims and quality of art was naturally heightened when public monies were being spent on the creation of art during a national crisis, at a time when the need for such funds was deep and widespread.

One controversy in New York concerned differences over aesthetic tendencies, with critics expressing concerns about the risk of favoritism on the part of Mrs. Force for modernist artists over traditional ones and the exclusion from the administration of representatives of traditional groups. On the other hand, there were artists who felt themselves unduly constrained by what they perceived as PWAP’s objections to abstraction.[16] Another dispute, perhaps fed by some confusion or uncertainty in Washington, had to do with the extent to which talent and skill should be important factors in the awarding of PWAP jobs. Edward Bruce specified a dual standard for the selection of artists: the artist had to be in genuine need and professionally competent. He wrote to Mrs. Force at the outset of the project that a phase of “this work, of course, is to put men to work, but I think that we ought all remember that we are putting artists to work and not trying to make artists out of bums.” He saw PWAP not as a relief measure, but as a public works program to employ artists to make public buildings beautiful. The tension or uncertainty around this issue was never perfectly resolved in the brief life of the PWAP.[17]

There was also a controversy over politics, with militant artists picketing and protesting at the Whitney and in the streets.[18] The leadership of the PWAP specified that artists were to interpret the “American scene” and so foreign subjects were to be avoided. “The goal of the PWAP was a permanent record of the aspirations and achievements of the American people.”[19] Some artists sought to present radical visions of American life that were out of keeping with the ethos of the leadership and there were some controversies about such works elsewhere in the country as well.[20] According to one scholar, however, “[t]he large majority who received PWAP checks did not feel compromised by conforming with PWAP’s definition of the American scene.”[21]

The Artists Union in New York protested against what it considered to be unreasonable limitations upon the number of artists who could be employed, but there were real difficulties, with the quota of positions for the New York region in February 1934 being 500 artists, although 4,000 artists had registered with the program in Manhattan alone.[22] The need was greater than the funds available.

The Public Works of Art Project lasted for only about six months, through June 1934, although ad hoc arrangements were made to finance the completion of work that was not finished at the formal end of the Project. During this brief period, over 3,700 artists received checks and in return produced 15,663 pieces of art and craft. Although that is a significant reach for a program in operation for such a short time, most of the artists in need of employment in America were not helped by PWAP and of those who were, about 50 % were non-relief. No direct means tests were used to administer the program.[23] These limitations or shortcomings, if you will, presaged a broader relief-based program to come.

Murals constituted only a small percentage of the work of PWAP. Although there was great demand for murals, there were a limited number of experienced muralists. Nevertheless, murals received attention far out of proportion to their number. The mural was, after all, well suited to fulfill the objectives of the program, being art that serves to decorate what is often public space and thus art that can be available on a permanent basis to the public in a way that other art will not be. Art project rules – – and of course there were rules – – allowed artists to decorate any public building, federal, state or local. “Government art became chiefly mural art in the public mind.” [24]

The Treasury Section of Fine Arts

Aid to art was also supplied during the Depression through the Section of Fine Arts in the Treasury Department. The Section, which was inaugurated in October 1934, after the end of the PWAP, and was again under the leadership of Edward Bruce, sponsored and oversaw the decoration of new federal buildings, including office buildings and many post offices, with an emphasis upon assuring the quality of the art produced. An emergency program for the construction of courthouses and post offices across the country was in place under the control of the Treasury Department, which had historically had responsibility for such construction. Secretary of the Treasury Henry Morgenthau issued an order that one percent of the total cost of each building would be allotted for decoration, and this was intended to provide the financial underpinning for the Section of Fine Arts. The artists who obtained the work would be assigned contracts, as in any other job involved in the construction of federal buildings, and thus would be independent contractors and entrepreneurs. This method of administration meant that this art program could be viewed as a part of doing what the government had always done, building and decorating federal buildings, now merely on a different scale; thus, the effort could be seen as being not truly, or at least not primarily, a matter of relief, which made it more palatable to the public and to political forces opposed to or doubtful about the New Deal.[25] In contrast, the Federal Art Project, which I will discuss shortly, distributed work on the basis of financial need and its artists were employed directly by the government. The Section’s artists for the most part worked alone in their studios whereas artists of the Federal Art Project were often assigned to a group supervised by a master artist.[26]

Despite the loftiness of its aims and its undoubted successes, the story of the Section of Fine Arts is also one, in part, of complicated bureaucratic wrangling and inter-agency discord, including continuing tension between the Section and the Works Progress Administration, discussed hereafter, which must have been quite disheartening to those seeking to advance the arts in America while assisting artists during these challenging years. [27] Obtaining financing for the Section was an ongoing difficulty, which produced budgetary uncertainty. In practice, Secretary Morgenthau’s order resulted in the production of funds for the decoration of only about a third of the new buildings.[28] Even taking into account the difficulties in obtaining funds, however, “the Section,” one scholar concludes, “placed before the nation an impressive amount of mural, sculptural, and other art.” [29] The Section sponsored about 1,116 murals and 300 sculptures in federal buildings around the country.[30] The fact that the President, his wife, Secretary Morgenthau, and his wife all believed in the effort helped to protect the Section and its work.

A central feature of the Section’s administration was the competition. Before World War II diverted resources from this work, the Section sponsored 190 competitions in which 15,426 artists submitted 40,426 sketches.[31] The juries were mostly local, but they did not have final word on the winners; that was up to the Section staff in Washington. The Section encouraged initiative and action on the part of the local juries and urged them to seek out artists from the area involved or nearby to take part in the competitions and to solicit ideas from the members of the local community. The sketches of the competing artists would be reviewed anonymously, by the local jury and by Section staff in Washington. The staff would tend to approve the selection of the jury if that selection met the Section’s standards of quality and competence.[32]

Most of the work commissioned by the Section was not actually arrived at by awards to artists who prevailed in the competitions. Although it held 190 competitions, the Section eventually awarded 1,371 commissions. Most of the commissions awarded without competition went to artists who had impressed the staff of the Section by submissions in previous competitions.[33]

The use of competitions avoided favoritism and political interference in the assignment of contracts. It also gave opportunities to young and unknown artists. At a time of ideological conflict, the Section was able to and did assign projects to artists of every political persuasion. The Section was a failure when it came to assignments to African-American artists. It did, however, award many commissions to women; about one-sixth of the artists working for the Section were women. The Section also made special efforts to commission Native American and western artists who had not previously been recognized by the government.[34]

The Section supervised the work of its artists, including through the evaluation of commissioned work as it progressed, and at least one scholar asserts that the Section limited the freedom it afforded to these artists. Thomas Hart Benton, the great American Regionalist, was invited a number of times to work for the Section, but never did. He wrote to an administrator there in 1936:

If you can ever give me a contract in which all responsibility is mine, in which I am completely trusted to do a good job and over which no one but myself has effective rights of approval or disapproval I’ll work. Otherwise, I can’t be sure I’ll do a real piece of work.[35]

The Section sought art of quality and defined quality in a more or less traditional way. This meant that it excluded abstract and otherwise avantgarde work and favored realistic, representational work. It sought to advance a contemporary American art that was neither academic nor avantgarde, one that could be accessible to the general public. Thus, the art it produced was not at the leading edge of the currents in the art of the world of the time.[36] This fact has been the basis for criticism. But, some scholars observe:

To some, the Section’s art may seem to promote a middle-class, consensus view of the world, but in the 1930s … this positive vision reflected a confidence in the possibility of change. It was not a picture of the status quo but of a society undergoing fundamental improvement….[The art of the Section] was … true to the widespread belief that progress, based on the work, the efforts, and the faith of “the people,” would win out.[37]

The Section’s work revealed a tension between fine art and democracy. The Section did not want to impose art upon the people that they might find incomprehensible or offensive. This was illustrated by the exclusion of abstract painters, but also by the struggle that manifested itself more than rarely between the vision of the artist and the will of local or national committees that reviewed it.

While the Section strove to produce art of quality, it eschewed elitism in the sense that it did not confine its endeavors to the cities, where art had been most concentrated in the past. It was committed to making art a reality of daily life in small towns and rural areas across the country as well. A mechanism for achieving this end was the decoration of 1,100 new post offices across the country. The post office in those days was an important institution, often located on the main street in town, where ordinary citizens conducted normal business. It provided an ideal venue for the art the Section endeavored to promote. The Section sought to and did sponsor murals for these locations that would represent or reflect the lives, history, and concerns of the local community rather than themes that might be of interest to the great and remote national government.[38]

The Treasury Relief Art Project

By late 1934, the Roosevelt Administration was actively studying ways to address the need for more effective national relief. The Works Progress Administration emerged out of these deliberations, as explained hereafter. Treasury, which had not concentrated on relief programs, did not want to undertake a large relief art project on the scale proposed, particularly as it was to include music, drama, and writing. So, the WPA proceeded as the vehicle for programs of artistic relief. When the Section of Fine Arts in Treasury indicated that it could handle additional funds, the WPA made a grant of funds to Treasury in July 1935 for the decoration of federal buildings. These funds were to be expended by Treasury, not under the rules that applied to the Section of Fine Arts, but under the same rules as were applied by the WPA. This led to another effort within Treasury, which was called the Treasury Relief Art Project, the TRAP. Seventy-five percent of those employed by TRAP were on relief. The number of persons employed by this project was considerably smaller than those employed by the initial Public Works of Art Project.[39] Most of the work done by TRAP artists was for post offices,[40] although certainly not all; one of its most challenging and successful efforts was the decoration in fresco secco of the dome of Cass Gilbert’s Custom House on the Battery by Reginald Marsh, who, in 1937, with the aid of eight assistants, painted very impressive and dynamic harbor scenes and pictures of explorers.[41] One scholar calls these murals, which cover about 2,000 square feet, “by far the greatest achievement of the TRAP and quite possibly one of the most comprehensive and successful mural schemes carried out under the New Deal projects.” [42] An illustration of the kind of political pressure that artists working in the federal projects could encounter was the complaint made to the Secretary of the Treasury by the Chairman of the United States Maritime Commission, Joseph P. Kennedy, that Marsh was depicting foreign vessels, including the Queen Mary. To their credit, Secretary Morgenthau and Mr. Bruce stuck with Marsh’s designs.[43]

The Federal Art Project of the WPA

The principal federal project supporting art and artists was the Federal Art Project of the WPA. The Federal Art Project came into being in the following way. In late 1934, Harry Hopkins urged that President Roosevelt put in place a better relief program than that then in existence. The administration worked on creating such a program over the winter of 1934-35. Legislation aimed at achieving this goal was proposed and it was enacted in spring 1935. The Works Progress Administration was established later that year as the bureaucratic entity charged with carrying out the relief program. The WPA was intended to help workers doing work on what might be called a mass scale, such as construction workers. At its height, the WPA employed millions in improving the public infrastructure, such things as parks, roads, schools, and bridges. But the WPA was also to provide assistance to creative workers. Four separate units were established within WPA to provide support for artists, actors and theater workers, musicians, and writers. The Federal Art Project was the entity that addressed the needs of the artistic sector and artists.

Holger Cahill, who, among other things, had served as acting director of the Museum of Modern Art in 1932-33 and who had had a highly unusual, peripatetic, and adventurous life as a young man, was selected by Hopkins to be the director of the Federal Art Project,[44] which turned out to be an inspired choice. Cahill proved to be an effective administrator and skillful at avoiding the risks inherent in his position at the top of a public arts agency at a time when the public might be expected to harbor some concern about the practicality and utility of aid to artists. Cahill sought to give artists a place in American life and to persuade the broad public that they were getting something of real value in return for the government funds expended on art. Cahill said that “[h]is guiding principle . . . was to make a connection between art and daily life.”[45]

Looking to murals alone, Mr. Cahill reported in 1937 that in the first year of the Federal Art Project, 434 murals had been completed, 55 were in progress and sketches were being prepared for a great many others, with hundreds of requests for other murals pending and waiting lists in every section of the country.[46] By the end, the Federal Art Project produced 2,566 murals, as well as a great deal of easel painting, sculpture, designs and other art objects.[47]

The relief support programs provided for artists by the WPA’s Federal Arts Project received and distributed much more money, aided far more artists – – perhaps ten times as many – – and brought a great deal more art to the public than did Treasury’s Section of Fine Arts. The Section aimed to improve the economic situation for American artists and to enhance the artistic understanding and taste of the American public, but sought to achieve these things through the provision of the best art possible for federal buildings; as noted, the Section, in the words of one of its administrators, “was not set up to engage in widespread relief”[48] and sought to obtain a portion of construction funding for art to be placed in the buildings. The emphasis of the Federal Art Project was somewhat different because it developed as a part of the government’s larger program of public relief and relied for its financing upon relief funds. The principal concrete objectives of the Federal Art Project were to provide support for persons facing severe financial hardship and to preserve their skills, while contributing to a more artistically sensitive and informed public and presenting worthwhile art. Its leadership tended to emphasize, or emphasize more strongly, the encouragement of production of numerous works rather than fewer works of “high quality,” as did the Section, a standard that in practice was not always easy to implement. Holger Cahill believed that the making of a connection between art and daily life could better be achieved by aiming to produce much art, which could stimulate from artists much good, and even some great, art, rather than by favoring a select group of the “best” artists,[49] as the Section of Fine Arts was thought to do. Even so, the director of the Federal Art Project struggled to address the problem of artists of limited competence. If an artist was given a chance to demonstrate ability, but clearly failed to do so, then, the director believed, he or she ought to be moved into different but useful projects.[50] The Federal Art Project was better known and, in some quarters, more controversial than the Section.[51]

One of the administrators of the Treasury art projects reflecting years afterward on his experiences stated that “a healthy rivalry developed between the WPA [the Federal Art Project] and ourselves which stimulated each of us to outdo the other.”[52] He elaborated:

We … suggested that the Treasury was after “quality,” while the WPA offered “relief,” but the public has never made any distinction whatsoever. You still hear remarks about those WPA murals in post offices; and as to quality, both programs produced fine jobs. In fact, the inclusive net of WPA employment quite often achieved first rate results. It cost more, but then that money would presumably have been spent on relief anyhow. [53]

Beyond these differences in vision, or at least in tendencies, was a difference in administration. One scholar opined that one of the great advantages that the Federal Art Project had was that it had practicing artists supervising the activities of the various divisions of the organization, rather than well-intentioned, but inexperienced bureaucrats. The head of the Art Project’s mural division in New York, for instance, was Burgoyne Diller, who was an abstract artist “who showed an almost fatherly concern for the artists under him and great skill at turning bureaucratic regulations and restrictions to their best advantage.” [54]

The Federal Arts Project had a more dependable fiscal footing than the Section, but its future was nevertheless always in some doubt. Cahill believed that if Hopkins and Mrs. Roosevelt were to lose interest in it, the second tier of WPA administrators might undermine it. The Project had this in common with the Section of Fine Arts – – it was heavily affected by bureaucratic maneuvers and squabbling.[55] One scholar states that “[a] sizeable part of the New Deal art story concerns colliding empires, federal-state conflicts, and petty outrages of a thousand sorts.”[56] A persistent problem was the fact that the Federal Art Project necessarily had a different professional ethos than that which animated the WPA generally. As the WPA had been designed to address relief for large numbers of people engaged in mass activities, such as construction projects, its patterns of employment and rules often fit uncomfortably with the work of artists. It did not easily accommodate “workers” who had never been involved in mass projects or subject to industrial discipline or standardized commercial requirements and many of whom worked as individuals. Early on, for instance, Cahill had to bring to Hopkins’s attention the unsuitability of a WPA rule that placed artists on a working schedule overseen by a timekeeper, who would conduct random inspections from time to time. Hopkins approved Cahill’s experimenting with an honor system for artists, in which artists were judged not on how many hours they put in, but by their completion of projects on a reasonable schedule, but administrators in the states in question demanded a return to the rule out of fear that they might be blamed for a waste of funds.[57] One can easily imagine the fury with which Michelangelo would have reacted to any similar rule.

Audrey McMahon, who served as regional administrator of the Federal Art Project in New York City, New York State, New Jersey, and, briefly, Philadelphia, remembered decades later a period when the Federal Art Project operated “under the thumb,” as she put it, of the WPA administrator for the area. This administrator disliked the Art Project and did not understand it or art or artists and held a deep belief that creating a painting was not “work.” He also believed that the art projects were centers of extremism, which it was his duty to “clean up.”[58] Mrs. McMahon stated that he and she were diametrically opposed and, “looking backward, I realize with a certain amount of joy that I must have been as great a burden to him as he was to me.”[59]

In view of the relief nature of the Federal Art Project, it was in the early days required that 75% of the artists employed by it be on relief, a figure that was later increased to 90%. This created difficulties for the administrators, who needed some flexibility to be able to find technically competent supervisors for the large mural, sculpture, and other projects and experienced artists able to provide leadership to the less experienced. To receive relief, artists had to meet a “needs” test, which sometimes caused real hardship. Adding to the challenges was, in Mrs. McMahon’s words, “a horrifying uncertainty as to the duration of Project employment, which … seeped down to the artists, [and] was vastly detrimental to their efforts and morale.” [60]

The WPA was built upon a principle of cooperation between the federal government and state and local government, which contributed part of the costs. This arrangement made sense politically, but it also led to many quarrels and administrative difficulties for the Art Project.[61] Holger Cahill did his best to refrain from interfering with the style and subject matter of the artists’ work, including the muralists. There were, however, notable instances of controversy when local agencies or the press found fault with the subject matter, artistic purpose, or style of work done by muralists in the Federal Art Project. [62]

There were also many disputes over the years between the federal programs and artists unions over the number of available jobs and government rules. One of the Treasury administrators confessed years later that, in his opinion, “[i]t was grotesque and an anomaly to have artists unionized against a government which for the first time in its history was doing something about them professionally.” [63] Mrs. McMahon took a more charitable view of the matter. The unions made the administrators’ work more complicated, but, in her opinion, their basic purpose was similar, if not identical, to hers. Still, the fact that they were often on the same side of the issue “did not serve to soften many bitter encounters.” [64] The activities of the unions, which included picket lines, sit-ins, strikes, and building takeovers, also “did not help the image of the Project in the public eye.” [65]

For all of the difficulties encountered, however, Mrs. McMahon reflected on the Federal Art Project decades afterward with some satisfaction:

That we had a political administration which subscribed to [the idea that work was both essential and a good way of life], and would not humiliate us with a dole, but offered us a chance to ply our crafts, was the most wonderful possible circumstance, and that there were public places where the fruits of our labors were wanted and, indeed, needed, was balm to our souls. So, naturally, we did the best we could, and that best was very good. [66]

A historian, who presumably was more disinterested, looking back from the perspective of 1968, wrote that the federal art projects were

effective in aiding both established and unknown artists during a time of economic crisis, imaginative in their support of all areas of artistic endeavor and, most significant of all, productive of some of the best art of the decade.

He concluded that “these projects constitute a major turning point in the cultural history of our nation ….” [67]

The WPA and the several federal arts programs came to an end by spring 1943, at which time, the country being at war, unemployment had ceased to be the grave problem it had been during the height of the Depression.

The art projects had important effects on mural art in America. They stimulated a revival and intensification of interest in mural painting in the United States. Such interest had begun to develop in a serious way in the second half of the 19th century, at which time the work of John La Farge was highly influential, and in the early years of the 20th century a group of able artists specializing in mural painting had emerged, including Maxfield Parrish, H. Siddons Mowbray, and Edwin H. Blashfield. Mowbray, whom I will come back to later, and Blashfield were among ten leading painters who contributed to create the spectacular murals that adorn the courthouse of the Appellate Division, First Department on Madison Avenue in Manhattan, which opened in 1900. In the 1920’s, mural art in America was given a boost when the government of Mexico supported public mural projects that became well-known and influential, including the work of Diego Rivera, Jose Clemente Orozco, David Siqueiros, and Rufino Tamayo, and some of the leading Mexican muralists spent time in the United States, which helped to disseminate the influence of Mexican mural painting around the country. The Museum of Modern Art presented an exhibition of the work of 35 painters in 1932 that emphasized and elucidated the importance and value of mural painting.[68] From the days of the Civil Works Administration, the opportunities for artists to work on murals and their interest in doing so saw “continuous and dramatic” development.[69]

Some of the new energy favoring murals in the 1920’s through the 1940’s was a reaction against and away from the traditional line of mural decoration, which, in the eyes of some critics and painters, was excessively sentimentalized, overly ornate, almost baroque in its approach to themes and style. Whereas older muralists were often given to elaborate and complex allegorical representations of highly idealized, sometimes historically inaccurate, grand themes, such as in the case of The Apotheosis of Washington by Constantino Brumidi in the dome of the U.S. Capitol Building, some newer muralists wished to paint in a modernist representational style that was not highly idealized though not strictly realistic, as in the cases of Orozco and Rivera or in the flowing paintings of the Midwest of Thomas Hart Benton and John Steuart Curry, or, in some cases, those of Siqueiros, Tamayo, and Stuart Davis, for instance, in an abstract expressionist manner. There was also a desire to pursue themes that were more reflective of the realities of social life and of history. Some of the new muralists, such as Rivera, Siqueiros, and Davis, were advocates and practitioners of a highly politicized and controversial art, and both Benton and Curry encountered criticism when they painted murals about parts of history that were uncomfortable for their neighbors.

A great deal of work in murals, including those at the New York County Courthouse, was achieved through the art projects. The PWAP, the Treasury programs, and the Federal Art Project produced over 4,000 murals between 1933 and 1943; close to 400 of these were executed in New York City and State.[70] A large number of murals were created for the World’s Fair in Flushing Meadow in 1939-1940, although only a small number were sponsored by the Art Project because of its requirement that its art had to be permanently allocated to public buildings.[71] Over 60 % of the murals painted in New York under the Federal Art Project were on canvas, whereas the Fine Arts Section of the Treasury preferred fresco, as there was a desire to follow the lead of the Mexicans,[72] as well as traditions going back many centuries.

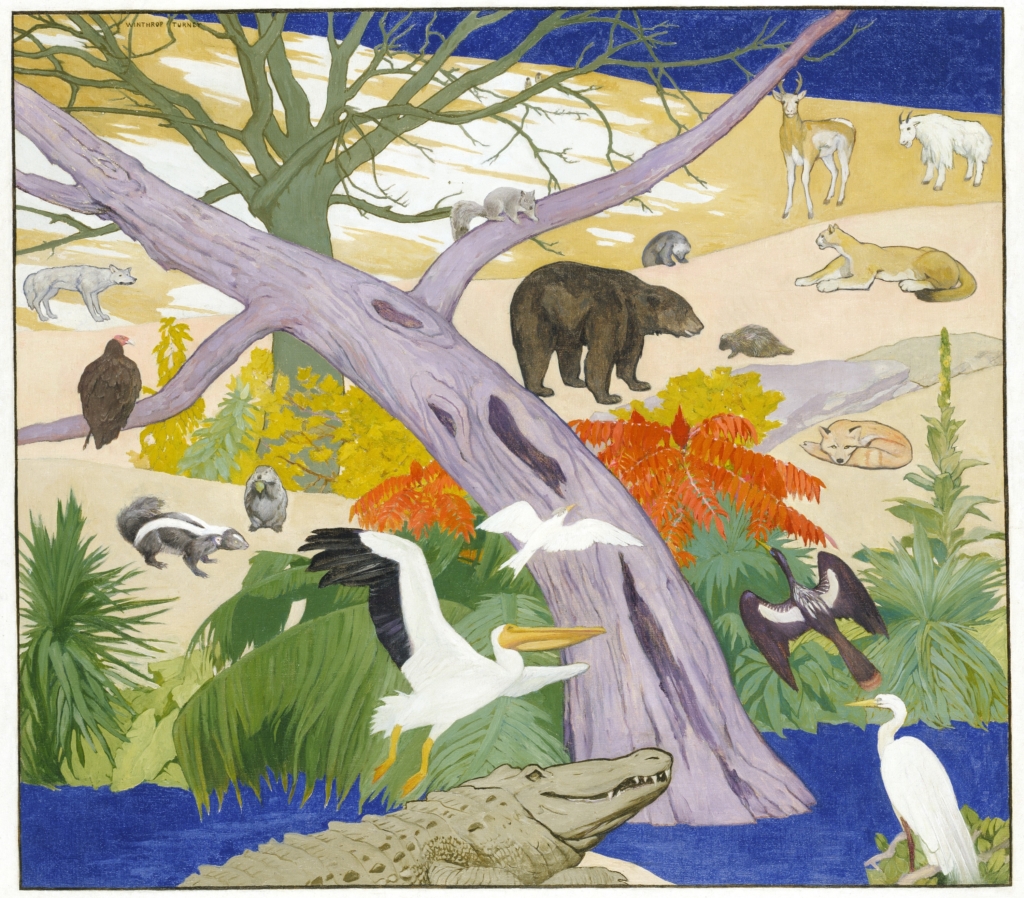

A variety of styles were employed in these works. At Newark Airport, Arshile Gorky did ten huge panels covering over 1,500 square feet of canvas in an abstract style on the theme of “Aviation” (1937). This was thought to be the largest abstract mural created under the Federal Art Project. James Brooks painted a mural, entitled “Flight,” in a blend of abstract and figurative styles for the Marine Air Terminal Building at LaGuardia Airport. Completed in 1942, this work covered a vast space, 2,820 square feet. Marion Greenwood, who, among other things, had studied with Orozco and Rivera in 1932 and worked in Mexico, painted a fresco for the Red Hook Houses in 1940, “Blueprint for Living,” that was influenced by the Mexican style. One of the most ambitious of the murals done under the Federal Art Project in New York was Edward Laning’s mural for the Aliens’ Dining Room at Ellis Island. This work, completed in 1937, was entitled “The Role of the Immigrant in the Industrial Development of America.” Painted in a dramatic, naturalistic style, it covered 1,000 square feet of canvas. The artist, who later, in 1940, did celebrated murals for the Art Project, “The Story of the Recorded Word,” that today lend beauty and an appropriate dignity to the McGraw Rotunda at the New York Public Library’s Schwarzman Building, obtained the commission for the Ellis Island project after the government bureaucrat in charge of the location had rejected the sketches of a predecessor and brow-beat him into withdrawing. [73]

C. Federal Support for the Murals at 60 Centre

Once it became clear in December 1933 that funds would be available from the then-new PWAP to pay the principal artist and his assistants, the Municipal Art Society of New York City submitted the murals project of the New York County Courthouse to the PWAP for its consideration. The proposal, which at that point was directed only to decoration of the vestibule of the building, was approved by Mrs. Force, the PWAP regional director. The murals project at the County Courthouse reportedly made the edifice the first public building in New York to benefit under the PWAP program,[74] which is to say, the first to receive assistance from a Federal art program. There does not appear to have been controversy about the artist who would preside over the work. Who received jobs was often a source of disagreement under the Federal Art Project and to a lesser degree as well in the case of the Treasury’s programs, which, as noted, relied upon competitions precisely to limit criticism of its selections and avoid importunities from influential artists or their sponsors with political connections. In the case of the courthouse, the circumstances were different, the artist having been chosen by the architect and preparatory work for the murals having been done before the courthouse had opened in 1927. When the application for approval was made, the sketches and models that Mr. Pusterla had done prior to the courthouse’s dedication were dusted off and resurrected and he was understood to be the person for the job.

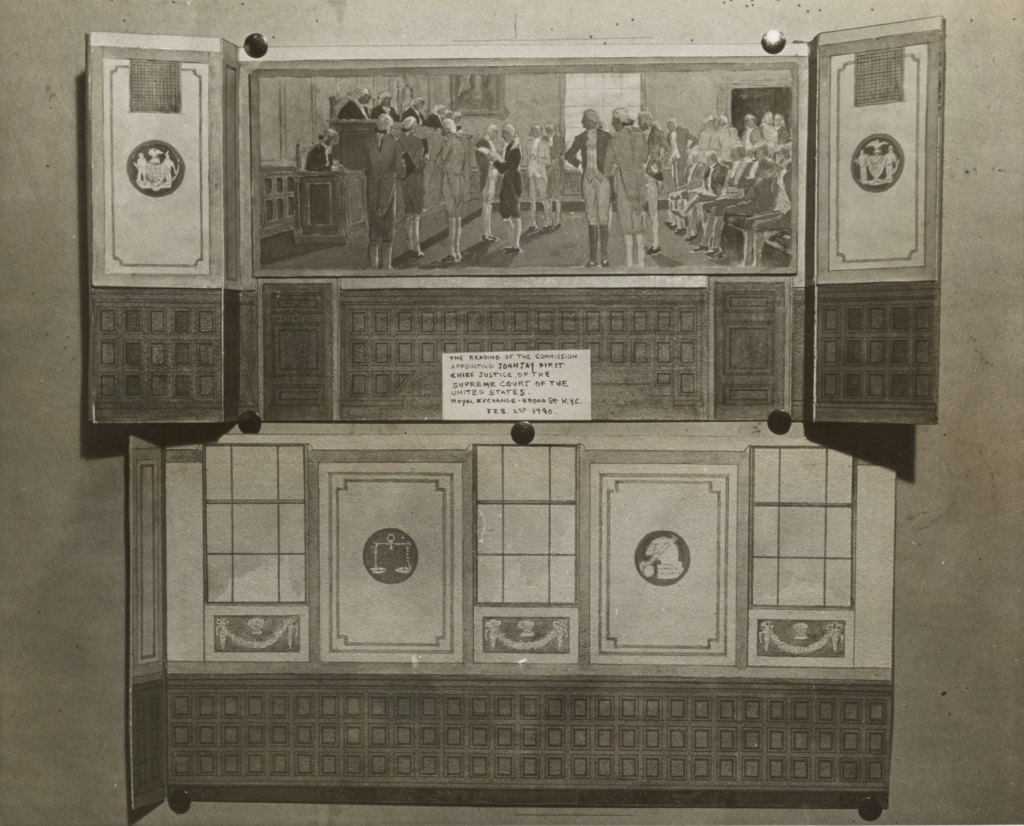

The mural project, because it involved changes to the interior of a building owned by New York City, had to be approved by the Art Commission of the City of New York (today known as the Public Design Commission). On January 9, 1934, Samuel Levy, the Manhattan Borough President, and Mrs. Force on behalf of the PWAP submitted an application for approval of decorations for the vestibule of the courthouse. The application was received on the same day it was signed and preliminary approval was granted that day (so much for the customary bureaucratic delay).[75]

It is appropriate here to note of the New York City Art Commission that

[i]n general it was liberal and cooperative, and its painter-member, Ernest Peixotto, was open to new ideas and young talent [and, in the case of Pusterla, senior talent too]. Most important, the artist was free to develop his work on his own beyond the sketch stage …. The result was a dynamic and productive mural division which produced a number of major murals in various styles ranging from the naturalistic to the abstract. [76]

The proposed project was also submitted to the judge who chaired the Court House Board, which approved the proposal. A room in the courthouse was then set aside for Lowell’s architectural assistant and Pusterla and the team of assistants, who were to help with the work and some of whom were to aid in executing the designs under Mr. Pusterla’s direction.[77] Thus, by early January 1934, only weeks after the inaugural meeting of the PWAP in Mr. Bruce’s house, the work was ready to proceed.

Although the principal financing for the project was through the government agencies mentioned, contributions for materials and equipment were made locally by the public.[78]

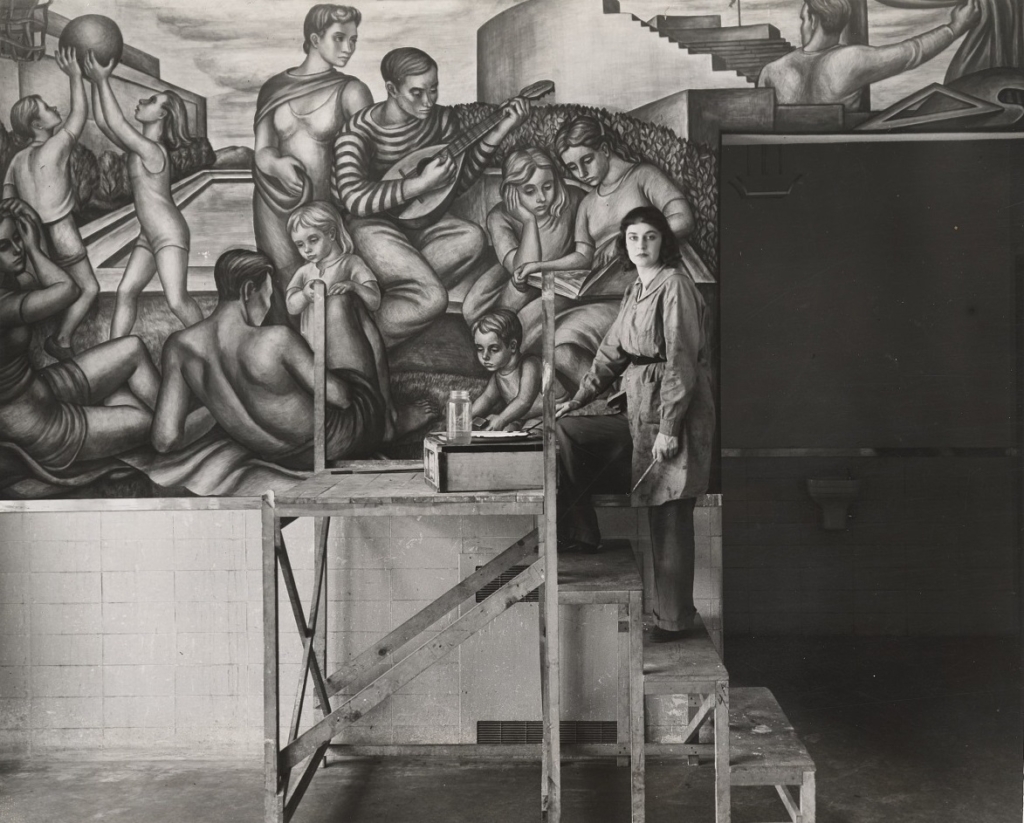

With funding available (although uncertain) to pay the wages of Mr. Pusterla and his assistants and with approvals having been received, the process of creating the murals began. Work commenced on January 8, 1934 in the vestibule, with Pusterla and seven assistants present and with a plan for the hiring of additional assistants soon thereafter.[79] In February 1934, it was reported that 30 assistant muralists or laborers or assistants of other types were at work on or in connection with the murals.[80] The top salary paid in the New York district by the Civil Works Administration was reported to be $ 34 per week.[81]

I do not know the identity of those who directly assisted Pusterla in the painting of the murals, but it has been written that at least some were students of his from the Leonardo da Vinci School,[82] where he taught, probably immigrants in at least some instances, like Pusterla himself, since the school was directed toward providing education in art for laborers and immigrants at little cost. That Leonardo colleagues or students would be appointed to these positions seems logical since Pusterla would have had personal experience with their talents gained over time. In order to receive an assignment from the PWAP and its later successor, the Federal Art Project, however, these assistants would have had to register and comply with government requirements, meaning that in the case of the Federal Art Project they would have had to have been in need and show competence in painting.

By April 20, 1934, the work on the vestibule was nearing completion, with two more weeks expected to be necessary to bring the work to a conclusion.[83]

As the work began on the vestibule, Pusterla and others involved no doubt hoped that funding would develop to carry out more extensive work elsewhere in the courthouse, but he was compelled to await developments as the funding story evolved. The aspirations for extensive painting in the courthouse must have been clouded in uncertainty, and this must have caused Mr. Pusterla considerable anxiety. The ceiling over the rotunda would have obviously presented by far the greatest source of worry for Mr. Pusterla and his assistants. In time, though, funding was found for the entire project.

After the vestibule was completed, the main, colonnaded corridor, which runs from the vestibule to the central hall, was the next area of work. The ceiling over the colonnade consists of two vaulted barrels and a dome. On April 11, 1934, Borough President Samuel Levy, with the endorsement of Mrs. Force (who noted, however, that the PWAP would soon come to an end), submitted an application to the Art Commission seeking approval for the decoration of the corridor. Preliminary approval was granted on May 8, 1934[84] and the painting was executed.

Work on the main corridor was perhaps followed by the decorative painting on the ceilings in the corridors on the first floor and on the ceilings of the second-floor corridors, namely, the area adjacent to the elevators running around the circumference of the main hall on the first and second floors, the five radiating corridors on the first floor running from the circumference of the main hall to the outer areas of the building, where courtrooms and offices are located, and the five radiating corridors on the second floor.

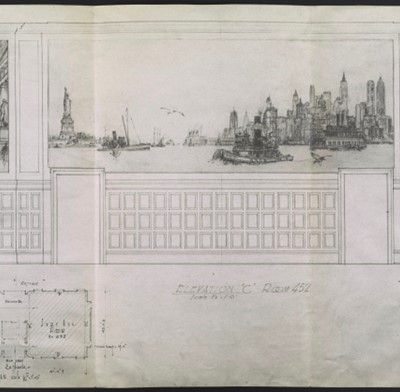

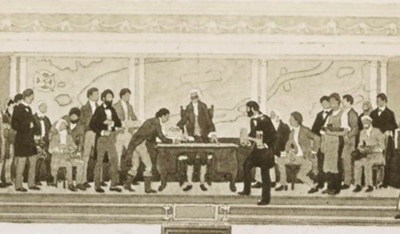

In September 1935, the murals project at the courthouse came under the jurisdiction and the supporting hand of the Federal Art Project of the WPA. Borough President Levy submitted an application to the Art Commission on October 3, 1935 seeking preliminary approval for a mural, that was to be entitled “The Law Through the Ages,” to be painted on the ceiling of the rotunda. Accompanying the application was a model of the ceiling, scaled one inch to the foot, that was decorated with the design the artist envisioned for the mural. The Commission gave that approval on October 8, 1935.[85] The Commission required that Mr. Pusterla consult with the Painter Member of the Commission, Ernest Peixotto, in the continuing development of the designs, that full-sized drawings of the designs as they developed be submitted to the Commission before the final work was to begin, and that final approval be sought before the mural was installed.[86]

Thereafter, Mr. Pusterla began the painting of the dome. This formidable undertaking, which involved the execution of a single painting rather than a series of separate but related panels, was said to be the largest work supported by the Federal Art Project in New York[87] and must have been one of the grandest ever executed under any of the art projects in the entire country. The Art Commission gave final approval to the designs in 1936[88] and the Federal Art Project’s mural division would have given its approval as well. It was anticipated that the murals on the first floor would be completed by July 1, 1936,[89] but that estimate proved to be optimistic, as so many estimates do. By March of 1937, some touch-up work still remained on the principal mural on the first floor and it was expected that the unveiling would occur within a few weeks’ time.[90] After the work on the first and second floors, murals were completed elsewhere in the courthouse, as I explain hereafter.

D. The Principal Artist

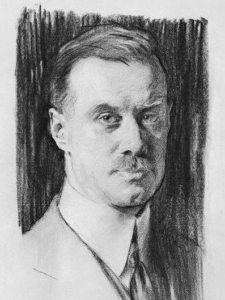

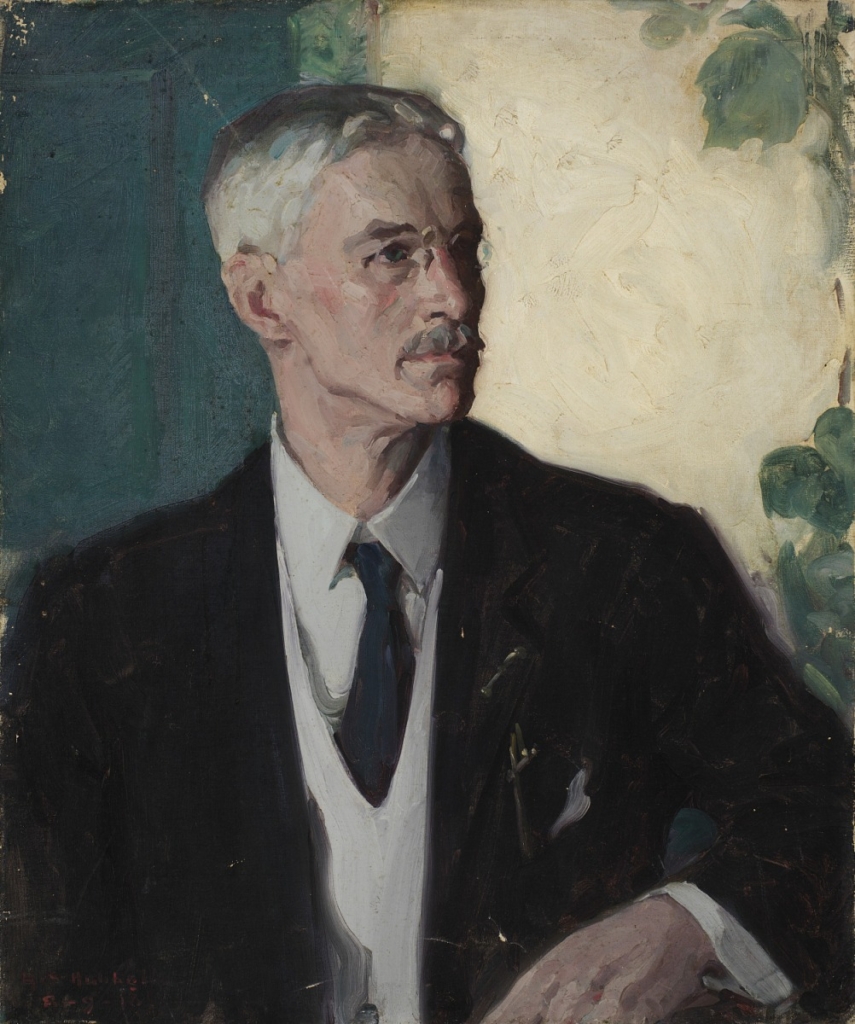

Attilio Pusterla, the principal artist and supervisor of the mammoth mural project at the New York County Courthouse, was an experienced painter, who had spent much of his life, but not all, as we shall see, working in that profession, for many years in Italy. He turned out to be a good choice for the challenging assignment.

The Life of an Italian Painter

Pusterla was born in Milan in 1862.[91] From 1878 to 1880, he attended the august Academy of Fine Arts of Brera in Milan, where he studied design, perspective, painting, and other subjects and where he became friendly with other artists associated with Brera who in time made names for themselves, such as Angelo Morbelli and Emilio Longoni. Thereafter, Pusterla spent several months at Lago Maggiore as a guest of a friend. He returned to Milan in 1883 and had his debut as a painter at Brera, where he presented four pictures. He exhibited at the International Exposition in Rome in 1883 and took part in exhibitions in Venice and in Milan in 1886. One observer in 1889 referred to his work as “very successful and praised,”[92] but, as we will see, his professional story was complicated.

Some of his friends, including Morbelli and Longoni, and other emerging artists such as Giovanni Segantini, Gaetano Previati, and Giuseppe Pellizza da Volpedo, became supporters and practitioners of a new artistic movement known as divisionismo (“divisionism”). This was a painting technique and philosophy, much influenced by science, in particular, advances in the understanding of human sight and how the eye perceives images, that looked on light as the foundation of artistic vision and sought to emphasize luminosity by setting forth bits of color closely together on the canvas rather than mixing the colors on the palette. This new technique “placed the rendering of light at the center of the act of painting …. “ [93] It took its name from its desire to “divide” colors rather than mix them on the palette, with the mixing instead taking place through the eye of the viewer. Various of the leading exponents and practitioners of the movement sought also to give content to a social and political vision in an Italy that had only recently been unified and was undergoing notable change and development.[94] This movement was influenced by, but differed somewhat from, “pointillism” in France. Whereas paintings in the latter mode used dots of color, the divisionists sought to apply small, narrow strokes of the brush.

Pusterla was taken note of by Vittorio Grubicy de Dragon, a painter, gallery owner, critic, and advocate for “divisionism,” and drew close to the circle of painters working in that style.[95] Pusterla sympathized with his friends, including in regard to their interests in the conditions of society, such that today, at the permanent gallery il Divisionismo in Tortona, Italy, three of his paintings form part of the collection.[96]

Pusterla developed an interest in expressing views of daily life in paint and documenting the social life of his time. As he progressed in his career, he become increasingly committed to an arte sociale, social realism and politically engaged art, not in the mere depiction of life and events. One scholar says of him that he was tied by anarchist/socialist sympathies to social realism as a manner of expression.[97]

In his interest in social art he resembled others of his colleagues, such as Emilio Longoni in his Oratore dello Sciopero (1891) and Pellizza da Volpedo with his impressive masterpiece, Il Quarto Stato (“the Fourth Estate”) of 1901, today in the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan. In this latter work, which is both beautiful and powerful, the painter shows a group of workers this large on the march to advance their economic rights.[98] The painting is notable for the balance of the composition and for the genuine dignity with which it invests the workers and the calm nature of their action. Pusterla’s increasing passion for this kind of painting is evident in his Poor People Begging, exhibited in Milan in 1885, well before Il Quarto Stato was finished, and today part of the collection of the Gallerie d’Italia.[99] In 1886, he presented paintings at an exhibition and at the Brera. He was associated with the Societa` per le Belle Arti ed Esposizione Permanente in Milan from 1886, when the Society opened a palazzo where it held exhibitions of fine art (known as “the Permanente”), until his departure from Italy.[100]

Pusterla also worked as an illustrator. In 1887, he provided watercolor drawings for a book of poetry by a friend. He also did some illustrations for journals, including Lotta di Classe (“Class Struggle”), the journal of the Socialist Party, and the cover for the Socialist Almanac in 1897, which reveal something of his political leanings.

Pusterla generated a great deal of attention with his presentation at Brera in 1887 of a large canvas entitled Le Cucine Economiche di Porta Nuova. In this work, Pusterla documented an aspect of the life of the poor and workers in Milan by depicting them eating food at a soup kitchen that had been constructed near the Porta Nuova a few years before, in 1883. In this period Italy was undergoing industrialization in the north, in and around Milan and Turin and elsewhere, the factories of which attracted many workers from around the country. Working conditions for these laborers were far from ideal, if not downright harsh. The area around Porta Nuova was one in which industrial establishments in increasing numbers, such as the Pirelli tire company, had opened and it was much frequented by workers. The soup kitchen created there had become an economic necessity for many workers, evolving in time into “one of the most important welfare institutions in Milan between the 19th and 20th centuries,”[101] virtually a symbol of poverty in Milan. This painting more than any other to that point in his career reflected Pusterla’s intention, not merely to depict scenes of beauty in landscapes and life, but to reflect routine but important aspects of the everyday life of ordinary people and to bring art to bear on the social problems of the day.

This painting generated “strong reactions, both for the subject and for the technique with which it was executed.”[102] Many painters of the time concentrated on creating landscapes, still-lifes, pictures of gardens, flowers, the sea shore and the like in which the purpose was to reflect and convey beauty and a sense of harmony with the world. Pusterla set aside that purpose in favor of depicting, with a harsh and unforgiving technique, a setting rarely seen in art, but all too commonly experienced by ordinary people every day. Pusterla sought to unsettle the viewer and make him or her think in a new way.

Some of his friends, it is said, urged him to soften the presentation of a scene that would inevitably be unsettling to many, but he declined to compromise. It is notable that the people depicted in the painting exhibit no signs of enjoying their meal, but appear to be going through the motions of dining while their minds are absorbed in thoughts of the unforgiving reality that awaits them when they finish. The painting is dominated by the action of eating, and only two persons in the foreground are differentiated from this action: a woman who seems to stare into space or at the viewer and a woman standing with a baby in her arms. Although the large room is occupied by people who are jammed in close together, to such an extent that it is impossible to see more than a small bit of the tables that fill the room, each seems caught in his or her own solitude.[103] The painting, a critic observes, is “contemptuous of any refinement as it is of any concern with trifling details, even being oppressive at times because the reality described is oppressive.”[104]

The scene is depicted with a crude realism, free of any ornament and free of any paternalistic tone, far from not only historic painting, but also genre painting … giving rise instead to a scrap of daily life in the dimensions of great painting.[105]

Despite the social purpose that animated this work, Pusterla hoped to receive the approval of the critics and a prize, but the latter did not come and the critical response was tepid at best, no doubt because of conservative resistance to the subject matter of the work and to its style. The painting did not sell in the exhibition, which of course did not help to cheer Pusterla’s spirits. Later, Vittorio Grubicy purchased the painting and, in 1888, showed it in London along with a group of 53 other works by Giovanni Segantini, Angelo Morbelli and other young Italian artists whom Grubicy favored as leaders of the emerging generation. The picture did not please the London market, returning to Italy unsold.[106] Eventually, the work was purchased from Grubicy by the Galleria d’Arte Moderna in Milan,[107] where today it remains part of the permanent collection. Despite Pusterla’s disappointment, this painting is recognized now as one of the seminal works of this period of Italian artistic history and it continues to be much discussed by critics and commentators, as can be seen from sources cited in the notes to this article. One commentator describes this work as “undoubtedly … one of the most interesting canvases in the panorama of painting in the second half of the 19th century.” [108]

Unhappy with the outcome of his work on this painting, Pusterla ceased showing in Milan for a period and took himself to Genoa and thereafter Florence.

In 1890, he exhibited in Bologna and in Turin.

In 1891, he returned to the world of Milanese exhibitions by participating in the Triennial Exhibition of Brera. A number of the painters of the divisionismo school took part in this exhibition as well and, indeed, it was here that that school truly burst on the artistic scene. According to one scholar, this exhibition represented “a decisive turn in the technique and aesthetic of painting in Italy.” [109] There were also a number of paintings presented that generated attention because of their social content, such as Longoni’s Oratore dello Sciopero. At this exhibition, Pusterla decorated the smoking room with a friend. He also presented a painting, The Blood Cure, that proved to be quite controversial. This work was set inside a slaughterhouse and centered on a dead animal and the figure of a gentlewoman afflicted with anemia who drinks a glass of blood as a restorative. Critical opinion was troubled by the choice of subject for this work. Nevertheless, it is said to have been “among the most significant paintings of the exhibition.” [110]

In this period, Pusterla was also engaged in creating pen drawings and paintings in oil.

In 1892, Pusterla executed decorative work. In the spring he painted a series of frescoes on the façade of a house in Milan; these no longer exist. He also participated in the Mylius competition for frescoes,[111] presenting a portrait of Giotto. That same year, he married Enrica Scotti, a seamstress.

In 1893, he traveled with a group of other artists to Chicago for the World Columbian Exposition. He and some of his friends, including Longoni and Previati, created a diorama recording the trip. He and two of these friends, along with a writer and a sculptor, planned to present a “Diorama Dantesco” at an art exhibition in Milan in 1894, but the project fell apart due to lack of funding. In 1894, he again participated in the Mylius fresco competition, presenting a portrait of Giovanni Bellini.

Around this time, he exhibited a painting in Venice (Riflessioni Dolorose (“Painful Reflections”)), which appears to be the one that is included with two others in the collection of the Divisionismo gallery in Tortona. In this picture, against an elaborate background, a seamstress working late at night thinks sad thoughts, no doubt about the financial challenges of life, as a younger seamstress nearby, perhaps her sister, has fallen asleep due to the arduous efforts of a long day.

In 1895 and 1896, Pusterla exhibited in Milan and Florence. One of the paintings he presented in the latter year was a second version of Le Cucine Economiche. It is not known why he returned to this theme, but it is notable that the atmosphere of this painting is more fraught and troubling than that of its predecessor from nine years before. Was this because he believed that social conditions had deteriorated, or was it perhaps due to his own state of mind? One critic observes that this second painting “sets itself far apart from its predecessor, not only in its general tone, which is decisively more melancholy and resigned, but also for the rendering of light and for the technique used in its execution.”[112] The colors in the second version are more somber than in the original, where the weight of the theme was relieved somewhat by the use of color, reds and blues, in the clothing of the subjects (although the blue was the color of protective attire often worn by factory workers and thus was in a sense necessary to the picture). Perhaps paradoxically, the painting is also melancholy because the hall of the soup kitchen is much less crowded than in the previous version; there are fewer people present taking advantage of the soup kitchen’s services, but those who are there seem to us even more isolated than were their fellows in the earlier painting.

There is some disagreement among scholars about the extent to which Pusterla was an adherent to divisionism. Some, for instance, have viewed the first Cucine Economiche as having been influenced by impressionism, while others consider that Pusterla was anticipating the divisionist artists.[113] The critic quoted above finds the technique used in the second Cucine much changed from that of the first painting, noting the long filament-like brushstrokes evident in the figure of the young woman and the surface of the tables that “show alignment with the researches of the divisionist painters.” [114] Another scholar says that in the Cucine Economiche Pusterla drew close to the divisionist experience, but that he still maintained loyalty to design and to constructive brush work in the creation of form that made him “more a participant in the great European realist tradition than in the various luministic movements.” [115]

It has been said that Pusterla had a “vast production” of works, including socially engaged paintings but also portraits and landscapes, in oil and pastel.[116] Some of these are in private hands today, and others have been lost. Despite this productivity, however, by 1898, if not before, Pusterla was very hard pressed by financial problems. These led him to accept an assignment to decorate a café in Milan. His last exhibition in Italy apparently occurred in 1897.

By the end of 1898, Pusterla was greatly discouraged. His finances were in disarray and he was troubled by the inadequate success of his work from a commercial perspective, and by what he felt to be the indifference of the critics. Further, he was embittered by the evolution of the social and political situation in Italy.[117] In 1898, after a steep increase in the price of wheat, there was unrest over bread prices in various cities around Italy. In Milan in May, there were large-scale strikes and riots. The army was sent in to calm the situation, but overreacted, with the general in charge ordering his soldiers to fire on an unarmed crowd with guns and artillery, which resulted in the deaths of at least 80 protestors and hundreds of wounded. This was followed by government repression nationwide.[118] In January 1899, Pusterla and his wife left Italy for the United States.[119] His departure represented a significant loss to Italy, as one scholar describes him as “one of the most important figures in the art of Lombardy of the end of the [19th] century.” [120]

Mr. Pusterla Comes to America

Every immigrant, even the most courageous — and they all must have fortitude to abandon familiar habits and surroundings and the family and friends whom they have known throughout their lives — surely struggles with misgivings and fears about the prospects for success in a new life in a new country and in a different language. Undoubtedly, Pusterla had such feelings. But he had a reason for worry beyond that which burdens every immigrant, every mason or carpenter who comes to America. He was cutting himself off from the ways of life, the scenery, the social and artistic contexts, movements, and community in and among which he had lived and worked for 37 years and that had been the vital fuel for his work as an artist. Surely, he must have feared that, far more than the mason or carpenter, he would have difficulty bringing his skills, so rooted in a particular social and artistic setting, to a country about which he knew little and at what is for a painter who is starting over an advanced age.

In 1904, Pusterla directed the Italian section of the Universal Exposition at Saint Louis. There, he attended to the placement of a painting of his friend Angelo Morbelli. To Morbelli he expressed bitterness about his first years in the United States.[121]

Among other work Pusterla completed in North America were murals at the Parliament Building in Ottawa, Canada. A fire in 1916 destroyed most of the Centre Block, where the Houses of Parliament are located. After the building was rebuilt, Pusterla was called upon to decorate the walls of the office of the Opposition Leader in the House of Commons. In 1920, he painted a series of frescoes, fourteen in number, on the upper walls, the only frescoes anywhere in the parliamentary complex. The frescoes depict scenes of knighthood and are intended to illustrate qualities, such as fearlessness, integrity, and wisdom, that the leader of the opposition ought to possess and that should help to advance the cause of beneficial legislation.[122] The Opposition Leader of the time, future Prime Minister William Mackenzie King, made many suggestions to Pusterla for the subjects of the murals, which the artist incorporated. King even went so far as to request that the face of an angel in one of the scenes be based upon that of his deceased mother, which, it is said, is what Pusterla did.[123] Images of the frescoes can be seen today in a publicly-available video.[124]

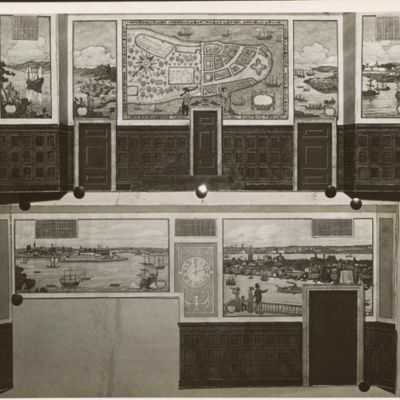

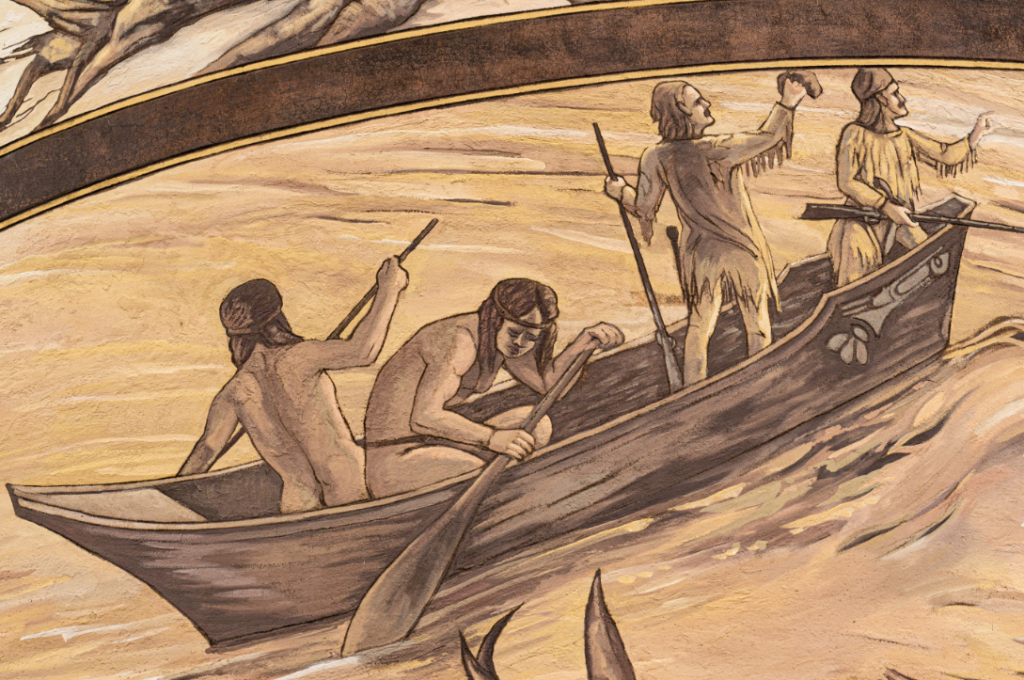

In the 1920’s, Pusterla painted a group of murals in the Senate of Canada, at least nine of ten, that celebrate the history of transportation and commerce in Canada. The murals show the daily life of ordinary Canadians, such as a lumberjack, a farmer, a miner, and a fisherwoman, in the early 20th century and before. They present images of ships, trains, canoes, and zeppelins set against Canadian landscapes. Unlike the frescoes in the House of Commons, the paintings were done on canvas, and they were affixed to plaster high up on the walls of the Railway Committee Room (also known as the Banking, Trade, and Commerce Committee Room) of the Senate of Canada in the Central Block of the Parliament Building.

In 2019, the Senate moved to a new building to permit extensive renovations to be made to its permanent home. Artwork in the building had to be removed for its safety during the renovations, including the Pusterla murals. Scaffolding was erected in the Committee room. The murals were peeled off the walls and immediately rolled onto cardboard tubes. Next, they were unrolled onto a protective sheet, rerolled, and transported to storage. This process can be seen in a publicly-available video. The murals may be cleaned and conserved while in storage. When the building is ready to be reopened, they will once again adorn the walls of the Commerce Committee Room.[125]

During the renovation to the Parliament building, it also became necessary to address Mr. Pusterla’s frescoes in the Opposition Leader’s Office to protect them from harm during the work. Using electric saws created specifically for the project, conservators cut into the walls and removed entire sections of the wall supporting each painting. A supportive skeleton was added to each section to ensure the stability of the plaster. In addition, each painting is being conserved to address discoloration, the effects of humidity (the Centre Block is located on the Ottawa River), and a build-up of salt on the surface that occurred over the more than a century since the images were painted. The frescoes will be reinstalled in the Opposition Leader’s Office once the renovation of the building is complete. A video is available that shows the frescoes and the protective measures taken to safeguard them.[126]

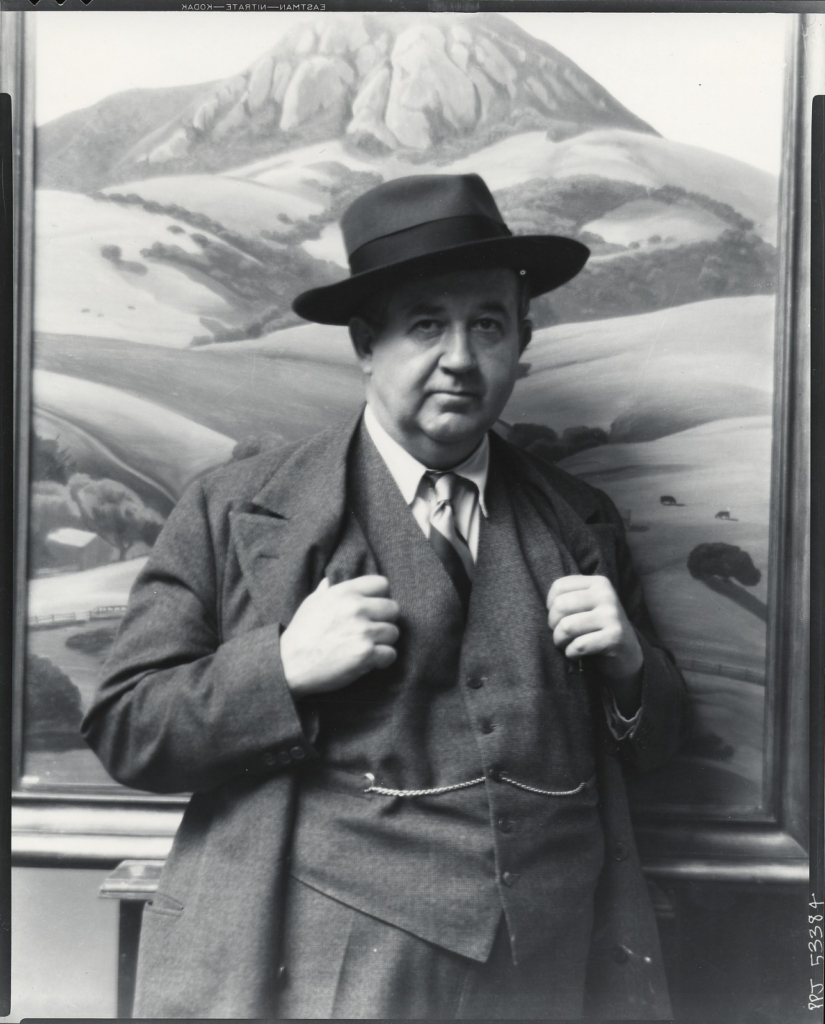

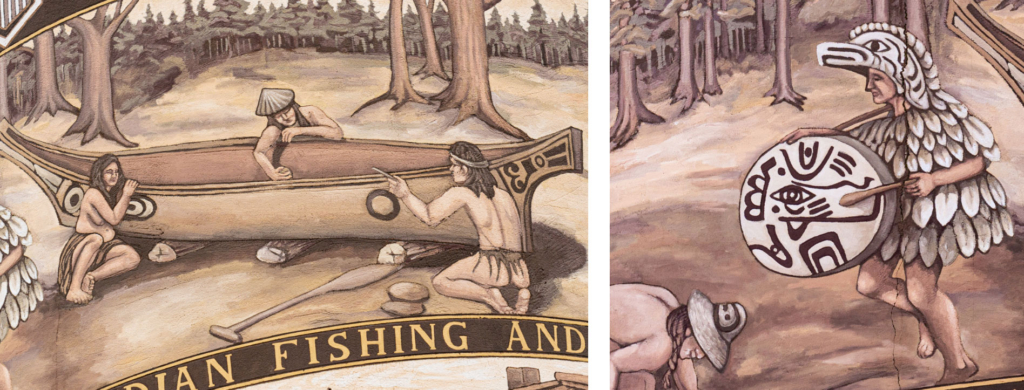

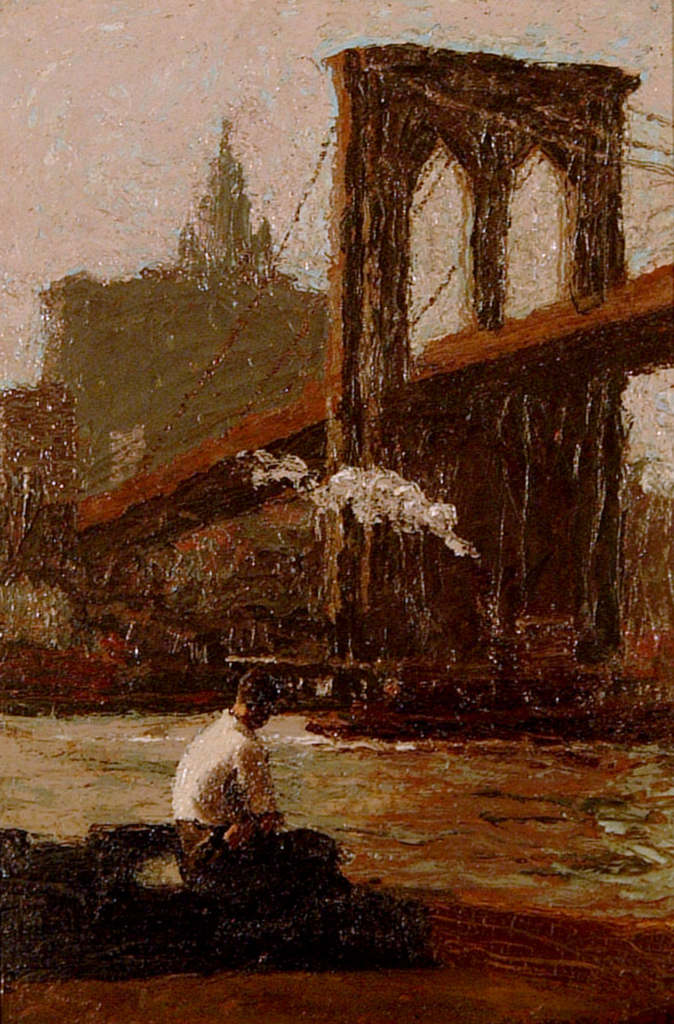

Pusterla received a commission to decorate a free-standing column that was erected in 1926 in Astoria, Oregon. The Astoria Column, as it is known, was designed on the model of Trajan’s Column in Rome. It is 125 feet high and sits on Coxcomb Hill, in a 30-acre park, overlooking the mouth of the Columbia River. The column boasts an interior spiral staircase and an observation deck at the top. The column was built with financing from the Great Northern Railway and Vincent Astor.

Pusterla designed a decorative strip, a kind of frieze, for the exterior of the column. The strip is nearly seven feet wide and runs the length of 525 feet. It depicts important events in the early history of Oregon and scenes from the history of the region, beginning with the pristine forest and the Clatsop and Chinook Indians, and including the first visit to the mouth of the Columbia by a Euro-American, Captain Robert Gray, in 1792, the expedition of Lewis and Clark’s Corps of Discovery in 1805, and the commencement of commerce at Fort Astoria by John Jacob Astor, from whom the location gets its name.

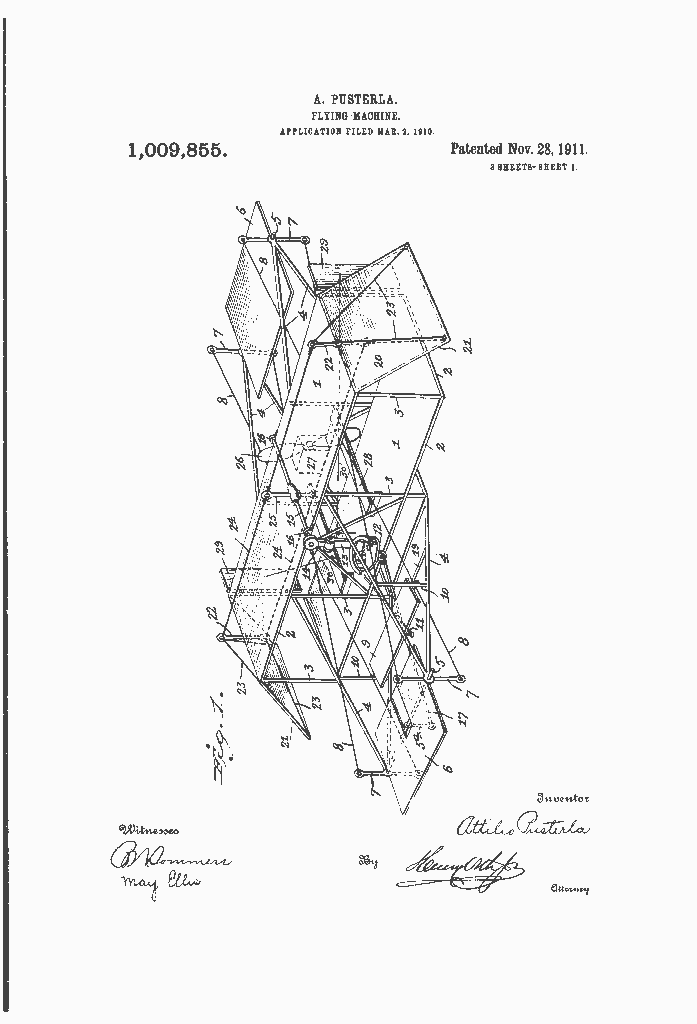

Pusterla created the frieze using an ancient method of carving or incising known as sgraffito (from the Italian graffiare, meaning “to scrape”).[126] In addition to its use on buildings, the sgraffito technique has often been employed over the centuries on pottery. Sgraffito was popular in the decoration of buildings, loggias, and the like in Renaissance Italy (two members of the studio of Raphael, for example, were expert practitioners of this technique) and it spread widely in Europe, to Germany, Poland, Portugal, Spain, and elsewhere. The artist using this technique applied two or more coats of plaster, contrastingly colored, to a wall. The artist would then scratch away from the surface coat while it was still somewhat wet in accordance with a pre-determined design, thereby exposing the differently-colored undercoat. The contrast in colors, such as between a dark undercoat and a light surface coat, allowed for the creation of elaborate images in the hands of a skilled artist.[127]

In 1926, Pusterla erected a scaffold that surrounded the entirety of the column. He laid down a base coat of dark plaster and later covered it with a lighter coat of plaster. He then created his design in the plaster using the sgraffito technique. The sgraffito artist would draw the design on paper, punch out the outlines of the design on the paper, delicately affix the paper to the surface, and then apply powder to the surface of the paper. The powder would seep through the holes in the paper, leaving the outline of the design on the surface of the plaster when the paper was removed. The artist would then, following the powder marks, scratch out the design with an awl, taking care not to scratch too deeply into the undercoat. This is the painstaking process that Pusterla followed in creating the frieze on the exterior of the Astoria Column.[128]

The column was dedicated on July 22, 1926, the central act of three days of celebratory events attended by thousands. Pusterla’s work was not finished on dedication day so he and his assistants continued laboring for several more months before the project was completed. [129]