By John F. Werner, Esq. and Robert C. Meade, Jr., Esq.[*]

June 2023

Introduction

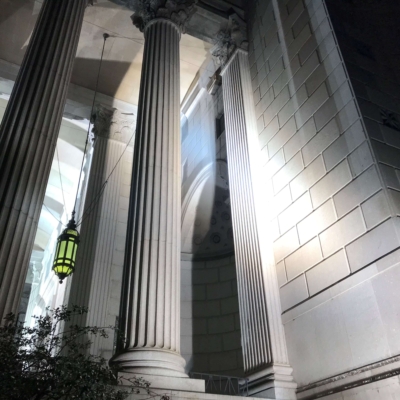

The New York State Supreme Court Building, also known as the New York County Courthouse, 60 Centre Street, New York, New York, is “one of the last neo-Classical public buildings erected in New York City and ranks as one of the best ….”[1] The Courthouse first opened its doors in February 1927, eight years after ground was broken. Although 60 Centre Street has since then been the principal courthouse for the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, the Appellate Term, 1st Judicial District, and the New York County Clerk’s offices, the Supreme Court outgrew the 60 Centre Street Courthouse in the 1980’s and the Court currently also has courtrooms, Chambers, and offices located nearby at 80 and 111 Centre Street and, less nearby, at 71 Thomas Street.

This narrative is mostly about the physical courthouse at 60 Centre Street and matters related. It would take more space than is available to attempt – – and it could only be an attempt – – to do justice to the efforts of the Justices, court staff, County Clerks and their staff who carried out the legal work of the court throughout its almost 100-year history. Thus, the story to be told here is not much about individuals, apart from the building’s architect, but rather about the building itself and its material aspects.

The Planning For and Creation Of the New York County Courthouse

Prior to the opening of 60 Centre Street in 1927, the Supreme Court, New York County had occupied the Tweed Courthouse, 52 Chambers Street, a courthouse with its own fascinating background and historical importance, which we will touch on shortly. At a certain point it was decided that a new courthouse was needed to take the place of the Tweed Courthouse. Some proposed that a new courthouse be built in City Hall Park. One proposal would have demolished the Tweed and replaced it at the same location with a much larger courthouse, a massive one that would have dwarfed City Hall. This was opposed by, among others, George McAneny, the Manhattan Borough President (1910-1913) and an important planner and preservationist, who urged that the courthouse be built north of Chambers Street.[2] He envisioned a civic center in the area where the new courthouse would be sited. There was talk at the time of the need for a Federal courthouse and a State office building and McAneny suggested that these buildings might become elements of the civic center. The construction of such a center would have the benefit of clearing away slum buildings in the notorious “Five Points” neighborhood. McAneny did not want, however, to maintain the Tweed Courthouse. He favored demolition of an unsightly post office located at the south end of the park and the Tweed. If this course were to be followed, he said, “we shall see the City Hall stand as it stood a century ago in the centre of the historic and beautiful common of the old days, though in the midst of the crowding wonders of the new.”[3]

When it became clear that the Tweed was not going to be demolished immediately and that its replacement was not going to be shoehorned into the park, a design competition was organized for a courthouse to be built to the north. McAneny looked to the acquisition of plots of land in the area to allow for the possible future construction of public buildings beyond the County Courthouse that would constitute a true civic center.[4] A consideration that favored locating the civic center north of Chambers Street was that the land values there were comparatively low, allowing the City to provide a site for the center at a favorable cost, even taking into account the increased cost of construction in the area due to the aqueous condition of the land.[5]

In late 1912, the Court House Board, the group that was overseeing the competition and the construction project, issued a statement that set forth the requirements that the competing designs would have to meet.[6] The Board was aiming at an ambitiously well-equipped and commodious facility. The Supreme Court and the City Court would both be housed in the courthouse, with separate entrances for each. The City Court was to have two special term courtrooms and ten trial courtrooms. For the Supreme Court, there would be four special term courtrooms, 10 courtrooms for the trial of equity matters, two courtrooms for criminal cases, 24 courtrooms for civil cases, and a courtroom for the Appellate Term. Chambers were to be provided for 40 Supreme Court Justices and 10 City Court Judges. There was to be a waiting room for the public, even public lunch and dining rooms, and a room for attorneys.

In 1913, the competition was held to select the architecture firm or architect to design the new New York County Courthouse. Twenty-two firms and individuals took part in the competition, including Cass Gilbert and McKim, Mead & White. A knowledgeable jury was designated to examine the plans submitted by the competitors and to make a recommendation to the Court House Board. Guy Lowell was chosen unanimously by the jury, which examined the submissions without knowing who drew them, and that choice was unanimously approved by the Board.[7]

From one perspective Lowell was an improbable choice for this important commission inasmuch as he was a scion of the very prominent Lowell family, which was, and indeed remains, closely associated with Boston, rather than with New York City. There is a famous saying about Boston which runs about as follows: “And this is good old Boston, the home of the bean and the cod, where the Lowells talk to the Cabots, and the Cabots talk only to God.”

Lowell was born in Boston in 1870. He graduated from Harvard College and received a degree in architecture from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in 1894. He also studied at the Royal Botanic Gardens in England and at the Ecole des Beaux-Arts in Paris. He was the architect and landscape architect for the Charles River Dam project in Boston (1910), in which the river was transformed into the Charles River Basin. One of his major commissions was the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston, which opened in 1909. Guy Lowell was also well known, perhaps even better known, as a landscape architect. He wrote three books, one on landscape architecture and two on Italian architecture.[8] He founded and taught in a program in landscape architecture at MIT, which ran from 1900-1910, in which he made a considerable effort to provide opportunities for women. Lowell was also an enthusiastic international yachtsman.

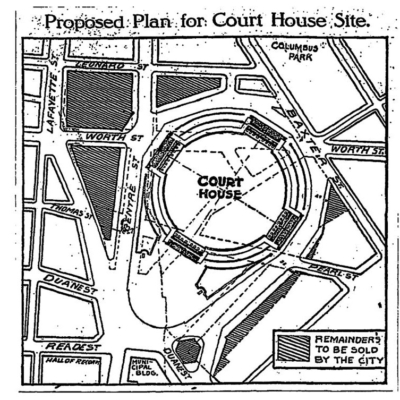

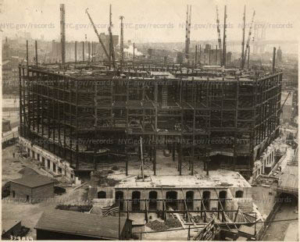

Although he began in the preliminary round of the courthouse competition with a design for a polygonal building, Lowell’s final design for the competition, which was inspired by the architecture of Rome, was for a massive round courthouse, which he felt was more suited to the demands of the site than his original conception. Among other considerations, Lowell said, was that with the circular form, “now the building does not have to turn its back on any street, or any neighborhood.”[9] The circular design called to mind in observers the Coliseum in Rome. Lowell was indeed inspired by the architecture of Rome, but by more than a single structure. He had been there a year or so before and had seen a model of what Rome had looked like at its apex. There had been many circular buildings at that time that had not survived.[10]

The building was to occupy 120,000 square feet of ground. In this design, the courthouse was truly to be massive: 500 feet in diameter and about 200 feet tall, which would, according to the editors of the New York Times, probably make it the largest courthouse in the world.[11] It was to have eight floors, four porticos with huge columns at the entrances, with one portico facing Columbus Park (which has been known as Mulberry Bend Park, Five Points Park, and Paradise Park),[12] another Centre and Worth Streets, a third facing east, and the last facing south. There were to be 80 other pillars in a row about two-thirds of the way up the structure. The design included a circular main hall on the first floor, where the elevators would be located so that users of the building would not have to search them out. The program for the competition stated that as much as possible offices connected with the court should be located on the ground floor and Lowell’s design met that requirement. Five floors were to be devoted to the trial of cases. One of the floors was to be assigned to the City Court and the others to the Supreme Court. As a rule, the courtrooms were to be arranged in groups of two, each with its own jury deliberating room. It was reported that the design contemplated that there be lightwells or light courts that would provide ventilation and light for the courtrooms. The light courts would not only bring natural illumination into the courtrooms, but the windows thereof could be opened so that ventilation could be obtained in the courtrooms without noise from the street entering and interfering with the proceedings of the court. It was envisioned that the subway would run beneath the building and that elevators in the building would run down to the subway level. [13]

Under the relevant law governing the project, the Justices of the court would have to approve or reject the design in order for the project to proceed.[14] After consultation, the Justices informed the Court House Board that they disapproved of the design. Several grounds were offered for this judgment, including what was expected to be the large cost of the building, lack of adequate ventilation, and, above anything else, lack of adequate light. Despite the reference to lightwells in the initial news report, the Justices asserted that the circular design allowed for light to enter the courtrooms from only one

side.[15]

By March and April of 1914, the Justices had come around to approving Lowell’s conception for a round courthouse with certain modifications made by him in response to their concerns. The Justices consulted with experts, who advised that the plans would provide for sufficient ventilation and light. In April, the Court House Board signed a contract with Lowell.[16] By the end of that month, demolition of old structures in the Five Points neighborhood had begun.[17]

Lowell was expected to net $ 100,000 to $ 150,000 for many years of work.[18]

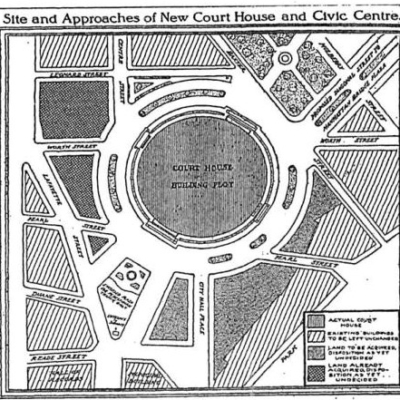

The site that the City had chosen for the courthouse and for which Lowell designed in 1913 was gigantic. On its west it bordered Lafayette Street and extended to Baxter Street on the east (the Federal Courthouse at 40 Centre Street did not open until 1936). The site straddled both Worth Street and Centre Street and extended to the north to Leonard Street so that the site was across Leonard Street from the location of the Tombs Prison (in its second incarnation, the first at the same location having been demolished in 1902). The site occupied almost all of what is today Foley Square. (The square is named after Thomas F. Foley, a leader of the Democratic Party.)[19]

As the deliberations surrounding the finalization of the design proceeded and demolition began, three problems became increasingly apparent and pressing. One problem was that locating the site as far to the west as the City had done and as far to the north placed it over some of the worst portions of the former Collect Pond.[20] The pond, which had derived its name from a corruption of a Dutch word for a “small body of water,” was large enough that Robert Fulton could use it as the location for a test of one of his early steamboats, and large enough that it served as the source of the City’s drinking water in colonial times and up until about 1813, when it was filled in and the ground leveled. The filling in did not, however, eliminate the aqueous condition of the ground that lay below. The watery ground caused significant and enduring difficulties for the original Tombs Prison, and the authorities were concerned about the suitability of the original site for the foundations of the courthouse. The editors of the New York Times offered the opinion that the selection of the site had been a “serious error.”[21] Moving the site to the east somewhat would ameliorate the groundwater issue, although, as it turned out, it did not eliminate it.

Another problem, as explained by Borough President McAneny, who advocated moving the site eastward, was that the original site would have interfered with street car lines that ran on Worth Street and Centre Street and would have required that Centre Street and Worth Street be “arched over.”[22]

The last problem had to do with the cost of the project. There was considerable worry on this count.

In the end, it was decided, therefore, that the site should be moved to the east somewhat, with its pivotal point to the south of where it had been in the original plan.[23] The site would still run to Leonard Street and would still straddle Worth Street, but a circular street around the planned courthouse would allow traffic to move north onto Centre and to the east. Portions of the land that had already been acquired for the original site but would no longer be needed could be, and were, sold. The property sales generated funds for the City that helped to defray the cost of the courthouse and the expense entailed in the purchase of some new land to accommodate the new location.

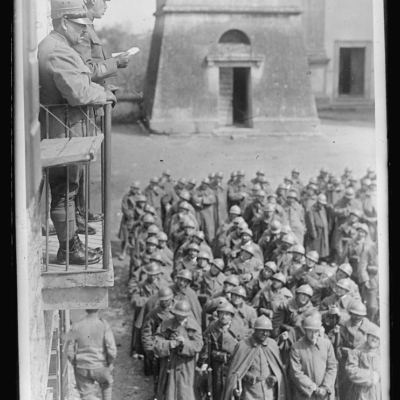

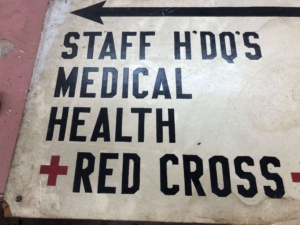

World War I delayed implementation of the plans for the new courthouse. While hostilities raged, the War Department built barracks on the courthouse site.[24] During the conflict, Lowell served as a Major and the director of the Department of Military Affairs of the American Red Cross in Italy, for which he was awarded by the Italian government the Medal of Valor and the Military Cross.[25]

After the war ended, financial considerations, as well as a change in the administration of the City, led to the definitive abandonment of Guy Lowell’s vision for a circular courthouse. It was estimated that, due to increases in the costs of labor and materials, the completion of the original plan would have cost $ 22-25 million, far in excess of the original estimates and much more than the City wished to pay.[26]

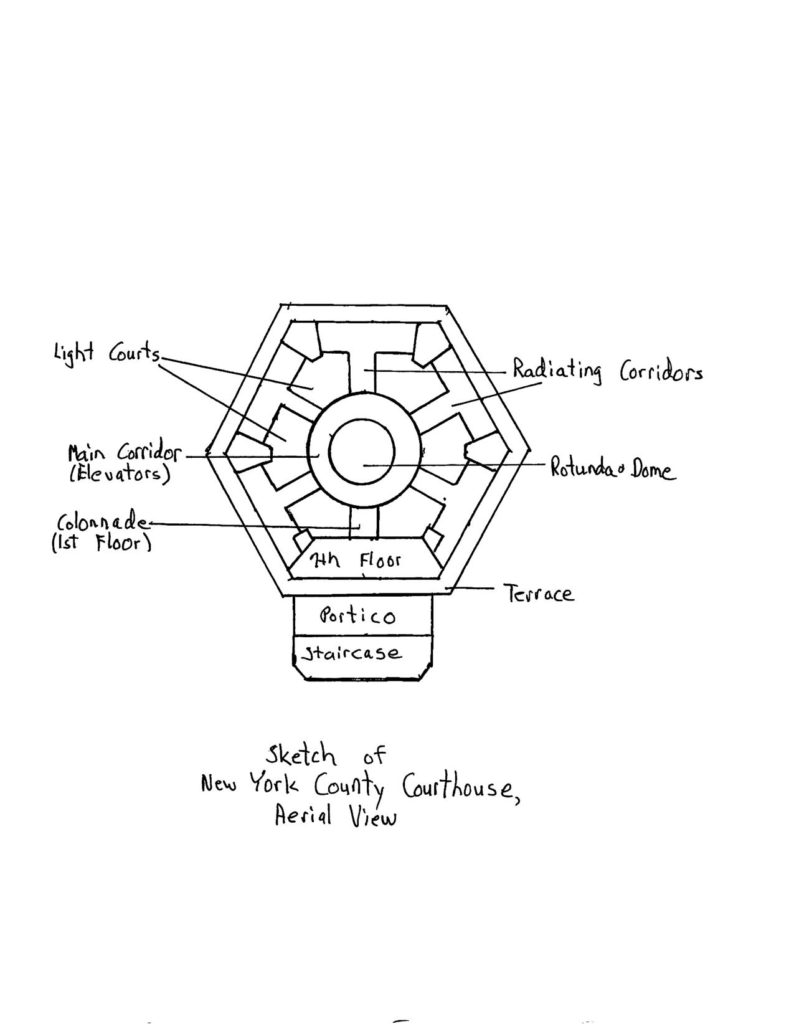

Guy Lowell went back to his original vision for a polygonal building. Within a short period, Lowell produced plans for the hexagonal structure that we know today and these plans were approved by around December 1919.[27] The new design was for a smaller building than the original, and the edifice would be built on the more eastward plot. Lowell’s revised design placed the structure so that it bordered on Centre Street, Worth Street, and Pearl Street, and therefore eliminated the need for a circular drive around the courthouse. The plans in 1919 contemplated 29 courtrooms for the Supreme Court and ten for the City Court, with the second floor being devoted to the latter. It was thought that if the workload of the Supreme Court should so increase in future as to require that the court have additional space, the City Court could be moved out of the facility to a separate location.[28]

Roughly put, the design placed the courtrooms away from the façade side of the building (although the ceremonial courtroom is located on that side) and on the other sides of the hexagon.

In his new plan, Lowell maintained his circular design for the central interior of the courthouse. At the center of the hexagon, as was the case with the circular courthouse proposed by him, he placed a large center hall, the rotunda. Lowell made an unusual choice here, in that, although the center hall has a dome and a cupola, they are interior features in this sense: to the observer looking at the building from the outside on Foley Square, it is not possible to detect that such a hall exists nor to see the dome and cupola. One can of course see the dome and the cupola looking up from the floor of the rotunda, but also – – and this is quite striking a sight- – one can look upon the exterior roof of the rotunda and the cupola from windows on the main circular hallway on the third floor.

Lowell carried over to the design another feature of the original circular courthouse, previously remarked upon, that he viewed as of considerable practical importance – – that the courtrooms were placed in distinct units of two, each with its own robing room and jury deliberating room. We explain later why this mattered to Lowell.

In his design Lowell also gave substantial attention to assuring adequate light inside the structure, no doubt with the objections of the Justices to his original design well in mind. We will also come back to this subject later.

In the new shape of his proposal Lowell retained the classicism that had defined his circular design. He kept a classical reference from his original design, the pillared portico. In place of the four entrances originally planned for the circular courthouse, he created a large, substantially projecting, and imposing portico as the main entrance for the hexagonal courthouse. The façade calls to mind the Pantheon in Rome, which, however, is not hexagonal. The portico was to be monumental, with a staircase leading up to it of 32 steps, 100 feet wide; ten huge, fluted Corinthian columns in granite facing the street in one long row, with two additional columns on each end of the portico behind the end columns in the row; a large roof structure atop; and a pediment. The pediment consists of a triangle 140 feet in length containing 14 classical figures in high relief. Atop the pediment are three statues representing Law, Truth, and Equity, the work of master sculptor Frederick H. Allen. The pediment bears the words of President Washington: “The True Administration of Justice is the Firmest Pillar of Good Government.” It has been reported that Mr. Lowell allowed a “typo” to establish itself in the quotation, which, it is said, ought to say, the “due administration.” [29]

It was estimated that the construction would cost $ 7 million and it was hoped that it would be completed in two years.[30]

It is enlightening to consider the cultural and architectural context in which Lowell was working between 1913 and 1927 and which influenced the courthouse he designed. In the years after 1900, the architecture and public areas of cities of antiquity gave inspiration to American architects and city planners, who reconsidered how best the public spaces and buildings of the city should be designed and laid out. In New York at this time, architects and publicly-inspired thinkers helped to establish what came to be called the City Beautiful “as a national movement aiming to reform and reorient American cities around classically inspired buildings and monumental plans emphasizing civic identity and public life.”[31] The advocates of the movement “sought to unify and aggrandize American cities through architectural and infrastructural projects,” and “appropriated classical models to embody the ideals of the civic leaders, professionals, and reformers who sponsored this movement.”[32] The architects and planners routinely adopted classical forms and motifs for public buildings and city projects across the country. They favored an eclectic, neo-classical style that was referred to at the time as American renaissance. This style emphasized “a mixture of classical elements, usually incorporating Renaissance and Roman motifs, with rich ornamental and sculptural programs derived from seventeenth-and eighteenth-century French architecture.”[33] The urban manifestation of this kind of architecture came to be known as the City Beautiful/Civic Center Movement. “American Renaissance designers believed that Greek and Roman architectural forms held moral and political meaning, and they deployed them to establish cultural and political legitimacy for a nation emerging as an economic and military world leader.”[34] In New York City, the City Beautiful philosophy “offered an image of order and control against what many saw as a chaotic and ill-defined city.”[35]

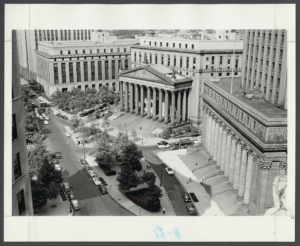

The civic center became an aspect of the City Beautiful “as a way to promote a collective vision for cities focused on architecturally coordinated spaces and monumental vistas.”[36] By the 1920’s, over 70 American cities had approved plans for civic centers.[37] The New York County Courthouse, as we have noted, was intended to be the founding element of a civic center for New York north of Chambers street. And in doing his work on the circular courthouse, Lowell had distinctly in mind, in his own words, that, “of all parts of checkered New York where a building had a fighting chance to enjoy a perspective from the converging of avenues, the one most favorable part was the little region near Worth and Centre Streets.”[38]

It took far longer to complete the construction of the courthouse than was originally hoped, but by the beginning of 1927, 14 years after the design competition, the building was ready for occupation. New York City and America in those days were living through a time of great energy, optimism, creativity, and more than a little excess, no doubt a response to the hardship and gloom of World War I and the deadly flu pandemic of 1918-20. The “Roaring 20’s,” they were called. There was increased prosperity, but also malfeasance. Prohibition was in place, but was very widely disregarded by the public, many of whom frequented illegal “speakeasies.” Only a few months after the courthouse opened, Lindbergh flew across the Atlantic and changed the world. That year, the first true “talking picture” was shown in theaters and the New York Yankees enjoyed a stellar season. Of course, no one could foresee the economic calamity that was to occur only a little over two years later and the horrors of the world war that was to follow.

As the opening of the courthouse was being planned, it was decided that the needs of the courts and the County Clerk were so great that the City Court could not be accommodated in the new courthouse. When the Supreme Court moved out of its old home in the Tweed Courthouse, the City Court was to move into the latter. All of the records from the old courthouse were to be moved to the new in only three days, between February 17 and 19, 1927.[39]

The new New York County Courthouse was dedicated on February 11, 1927.[40] The dedication ceremony was held in the courthouse’s beautiful rotunda. Among those present were the Chief Judge of the Court of Appeals and future Associate Justice of the United States Supreme Court, Hon. Benjamin N. Cardozo, and two of his colleagues, Judges Irving Lehman and Frederick E. Crane, former Justice Samuel Seabury, President of the New York County Lawyers’ Association, and former Justice and Senator-Elect Robert F. Wagner. Charles Evans Hughes gave an address and the proceedings were broadcast over the radio.[41]

Unfortunately, one chair was empty. On February 4, 1927, Guy Lowell had died suddenly while on a cruise in Madeira, Portugal at the age of 56.[42]

The Importance of the Courthouse

In making the adjustments to his original plans that practical necessity imposed upon him, Mr. Lowell did his design work well. The exterior of 60 Centre Street became famous throughout the country and, indeed, the world. It might even be argued that the New York County Courthouse is the most recognizable courthouse of any in the United States after the home of the United States Supreme Court. The courthouse, in both its exterior and interior, represents for many precisely what an important courthouse should look like. The courthouse is so imposing, stately, and impressive in appearance that it has been used as a setting for innumerable motion pictures (among them, Twelve Angry Men, Miracle on 34th Street, and The Godfather) and many television programs, including countless episodes of Law and Order. At a certain point, especially after 9/11, increased security concerns necessitated a reduction in the access of the Law and Order crews to the interior of the building for productions. In order not to lose the setting of a 60 Centre courtroom for its trials, the production company constructed a very close replica of a 60 Centre courtroom in which to carry on productions. Along the same lines, the Utah Shakespeare Festival of Cedar City, Utah, in anticipation of its 2013 theater production of Twelve Angry Men, sent a set design team to 60 Centre Street to measure jury rooms and examine original jury room furniture to ensure that its theater set would resemble as closely as possible the 60 Centre Street jury room used in the film. Nothing less would do!

The exterior of 60 Centre was awarded New York City landmark status on February 1, 1966. This is what the Landmarks Preservation Commission wrote about the building:

The portico on the front of this great courthouse creates an extremely imposing entrance with its monumental columns and pediment surmounted by three large, sculptured figures. The sides of the building repeat the scale of the portico with impressive pilasters set between the windows. The remarkable shape of this building is notable, and the courthouse relates well in scale with its neighbors on Foley Square. The handsome detail and use of fine materials characterize it as an outstanding example of Civic architecture….

The hexagonal plan of this building alone gives it an unusual degree of importance. In addition to this feature, its imposing proportions and rich detail make it notable. It has an overall grandeur which is in keeping with its function in housing the New York State Supreme Court Judges for New York County.[43]

Portions of the interior of the building were awarded landmark status on March 24, 1981.[44] In its report the Commission observed that

the splendid interior of the Courthouse is remarkably unaltered… The spectacular rotunda, in essence the recreation of a splendid Roman hall, reflects the classical spirit that so strongly influenced American architecture during the early twentieth century. A tribute to the talents of Guy Lowell, the building is as much a civic monument today as it was when it open[ed] in 1927. [45]

Lowell intended that his Italianate neoclassical design for the circular courthouse, undertaken on such a huge scale, and its smaller successor would, in their different forms, both project the authority, predictability, and permanence to which our jurisprudence aspires, and the renown of the exterior and the interior are surely due in part to the fact that they evoke so well the ideals of justice that the courthouse has striven to provide for almost 100 years. It is sad to think that Lowell himself did not live to see the official dedication of his great work.

By itself, the courthouse was a great success and remains so today. But its construction also led to the development of the civic center that George McAneny and other proponents had sought to achieve. By 1936, the square was home to the Health Building (125 Worth Street, 1935), the New York State Building at 80 Centre Street (the Louis J. Lefkowitz Building, 1930), and the Federal Courthouse at 40 Centre Street (the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse, 1936). On the margin of the square was the Surrogate’s Court (originally the Hall of Records, completed in 1907). Later came the Jacob K. Javits Federal Building (26 Federal Plaza, 1969) and the adjacent James L. Watson Court of International Trade. Not facing on the square, but adjoining the County Courthouse is the Daniel Patrick Moynihan United States Courthouse (500 Pearl Street, 1996). From an artistic perspective, the result would no doubt disappoint the original proponents, who would have hoped for a civic center with more harmonious, unified, low-rise structures.[46] But one thing cannot be disputed: the New York County Courthouse is a jewel and, in the view of the authors, the artistic centerpiece of the civic center.

Courthouses, like the jurisprudence implemented within them, are far from static and immutable. They evolve as societies change, legal cultures change, and Justices and court staff, even the most admired and important, come and go. Generations of attorneys have practiced in this courthouse, and presumably generations of attorneys to come will do so as well. Among the constants – – in law, buildings, and in all things – – is change itself.

60 Centre Street has always been owned and maintained by the City of New York. More specifically, it has long been maintained by the City’s Department of Citywide Administrative Services (“DCAS”).

Thinking back on the opening of the new Supreme Court in 1927, one can imagine the excitement that was felt by the court’s Justices and staff and the wider legal community. For Guy Lowell, too, the prospect of the opening of the courthouse must have been a source of excitement and immense satisfaction, for he had been called upon to demonstrate great patience, persistence, and dedication in order to be able to see the project through its many difficulties over almost a decade and one-half. As the court relocated from the Tweed, 60 Centre Street was, however, in one regard, still a work in progress. In 1927, the new edifice was entirely devoid of its much-heralded murals, which came into being in the mid-1930s as a project of the Federal Government’s Works Progress Administration.

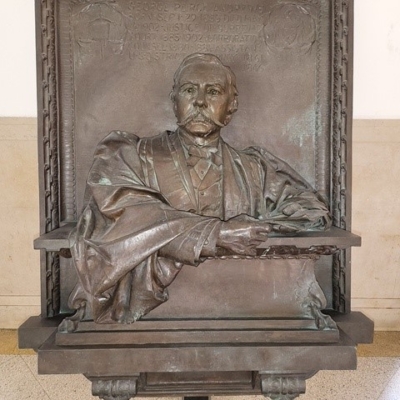

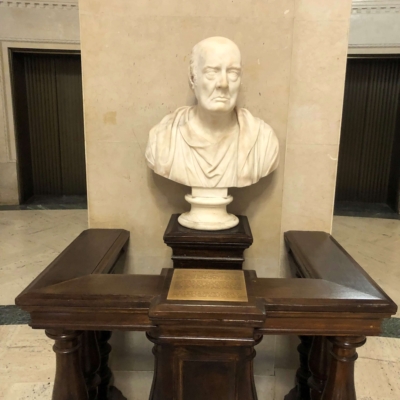

A marble bust of Guy Lowell adorns the lobby of the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston. A bronze cast of that bust was made and in 1928 was installed, along with notations in bronze of the subject of the bust and his dates, in a not-altogether-conspicuous niche in the entrance colonnade inside 60 Centre Street. The obscure location of the bust troubled the administrators of the court, who wondered whether it might be possible to bring greater attention to this tribute to the man who had created the courthouse. On the other hand, the administrators were reluctant to move the bronze casting from the perch into which those who had brought it to the courthouse had originally placed it. After investigation, the administrators hit upon and implemented a compromise solution: the original bust remained where it was placed in 1928 and a copy of it, indistinguishable from the original, was cast by Excalibur Bronze Art Foundry, Brooklyn, New York,[47] and since 2014, the copy has been on view in the great rotunda of 60 Centre Street, where it keeps company with a marble bust, crafted in Florence, Italy in 1828, of the Irish patriot, distinguished early 19th century Irish-American attorney, and former Attorney General of New York, Thomas Addis Emmet. Some years prior to 2014, the Emmet bust was cleaned and conserved and the cheap plywood pedestal on which it had rested was replaced with a pedestal and surround fabricated by DCAS carpenters from excess original courtroom rails, including spindles. A matching pedestal and surround were fabricated by these carpenters for the Lowell bust. The results of these efforts were harmonious and attractive stands for the busts that are well suited to the elegance of the rotunda setting.

The Tweed Courthouse

The Tweed Courthouse, the old New York County Courthouse, constructed from 1861 to 1881, was often maligned because the very lengthy process of its construction was associated with graft and with the machinations of the infamous Tammany Hall political boss, William M. Tweed, whose name informally became that by which this building was, and still is, universally known. The Tweed courthouse was repeatedly scheduled for demolition over the years, but it has survived, which is fortunate, as it is, despite the irregularities that accompanied its birth, a beautiful and important building.

After the Supreme Court moved in 1927 from the Tweed to 60 Centre Street, the Tweed continued to function as a courthouse for the then-New York City Municipal Court, a lower court. In 1962, the Municipal Court and the City Court were both merged into the Civil Court of the City of New York. The Civil Court for New York County commenced operations in a new courthouse located at 111 Centre Street, where it is today. After this, the Tweed limped on as a courthouse with summons parts and the like until the 1970’s. In the 1980’s, the court was gone from the Tweed.

In recent years, the Tweed has undergone major renovations and conservation and it now serves as the home of the New York City Department of Education. Before the Department of Education settled into the refurbished Tweed, Chief Judge Judith S. Kaye had urged then-Mayor Michael Bloomberg to return the Tweed to the New York State Court System. That would have been a very logical thing to do with a building designed and built to serve as a courthouse and would have shown the proper respect for the landmark status of the building. That was not to be, Mayor Bloomberg no doubt wanting the proximity of the Tweed to City Hall to serve as a physical symbol of, inter alia, his commitment to improving education in New York City. Today, the refurbished Tweed sparkles and what was once the “new courthouse,” 60 Centre Street, clearly shows its age, with very significant wear and tear throughout, as we shall note. The New York County Courthouse today falls short of the ideal in another respect. The Americans with Disabilities Act of 1990 has transformed architectural design since its passage, but older buildings have struggled, and often not successfully, to comply with the meaning and the spirit of that act, and 60 Centre Street unfortunately falls into this category.

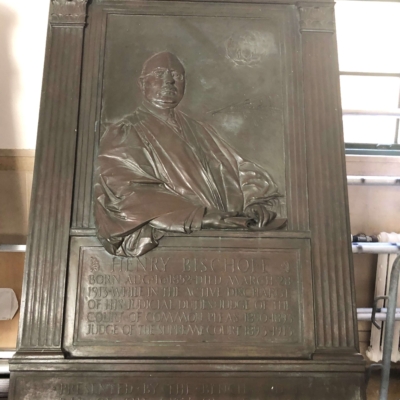

When the Tweed courthouse was still functioning prior to 1927, large bronze reliefs commemorating the lives of three leading and evidently highly respected judges who had presided in the Tweed had been created and installed there in courtrooms or corridors.[48] Some time after the courthouse moved to 60 Centre, the reliefs were placed in the basement of the Tweed, where they resided forlornly and unseen for years.

In the 1980’s or so, the existence of these reliefs came to the attention of the long-serving County Clerk of New York County, Honorable Norman Goodman. He arranged to have the reliefs removed from their “storage” in the basement of the Tweed and carried off to a conservator, who restored them. The reliefs were then brought to 60 Centre Street. During the renovation of 60 Centre that we will describe shortly, Mr. Goodman prevailed upon the construction management company for the project to fabricate three large metal stands to support the very heavy reliefs, which were then put on display at 60 Centre Street in the third-floor hall leading to the courthouse’s ceremonial courtroom, Room 300, where they remain. To tell the truth, the stands are quite unattractive and detract from the impact of the reliefs, but, as we know, one gets what one pays for, and they serve the purpose for which they were made, absent which, the reliefs would still be languishing unseen, this time probably in the basement or even sub-basement of 60 Centre.

The transfer of the forgotten reliefs to the New York County Courthouse turned out to be something more than fortunate or fortuitous. The deed of gift for one of the reliefs specified that it was to be moved to the new county courthouse when it was built. And so it came to pass, though it took some 60 years to get there.

The story of the reliefs reminds us that not every art object in the custody of court officials has been treated with the respect and care due. Elsewhere on the website of the Historical Society of the New York Courts, we tell the story of Rebecca Salome Foster, the “Tombs Angel,” who in the late 19th century and the first years of the 20th devoted her life to serving the court system and helping persons accused and convicted of crimes, including many immigrants, and their families, among them residents of tenement housing in the “Five Points” neighborhood, the very location today of 60 Centre and only two blocks or so from the site of the former Tombs Prison, where Mrs. Foster did much of her work. Mrs. Foster provided legal and financial assistance, helped the accused or convicted find jobs and homes, supported their families, and generally worked to set them on a path to a better and productive life far from the Tombs Prison and the world of crime. Mrs. Foster achieved immense respect in the legal community and outside it for her efforts on behalf of the forgotten. When she died, a public subscription was undertaken and with its proceeds, a memorial in commemoration of her life and work was created by Karl Bitter, one of the leading sculptors of the time in the United States, and, in 1904, this memorial was installed in one of the halls of the Criminal Courts Building in lower Manhattan. This tribute was at the time one of very few works of its kind in the United States honoring the life and work of a woman, a lacuna in our public life which continued for decades afterward and indeed still exists today and of which much notice has been taken in recent years. When the Criminal Courts Building was replaced in 1941, the memorial to Mrs. Foster was moved to the basement of the new building, at 100 Centre Street. Proper care was not taken, however, and the large bronze frame for the work and a sculpted marble medallion depicting Mrs. Foster were stolen, lost, or discarded. The central portion of the work, a sculpture of a ministering angel, survived, probably because its great weight (something like 900 pounds) made it too difficult to carry off; the relief was, however, damaged. Eventually, this portion was found, restored, and, in 2019, put on permanent display in the entrance lobby of 60 Centre.

60 Centre Street Murals and the Renovation of the Building

As impressive and well-known as the exterior of 60 Centre Street is, the courthouse’s interiors, including its major 1930s murals, are notable too, and deservedly so. We have made mention of the landmark status of parts of the interior. There are beautiful vaulted ceilings in the vestibule of the building; a long colonnade which slopes gently downwards to the rotunda, providing from the entrance area a unique vista of the rotunda; huge chandeliers; and, of course, the centerpiece of the entire building, the rotunda itself, a large, gracious space. Marble columns run around the rotunda and the multi-colored marble floor is very striking. Because of its great beauty, the rotunda, as it was at the courthouse’s opening, has been the scene of innumerable ceremonies of all kinds over the decades. Many of these, of course, have been programs and ceremonies for the court, its Justices, and its staff, but the court has also on occasion made the space available to groups. There have been many Continuing Legal Education and other educational programs held there and many bar association programs. The court presented an annual photographic exhibition in the space for many years and the Juilliard School put on free chamber concerts in the rotunda. For a number of years, the rotunda has been rented out (with the proceeds going to benefit the public) for receptions in connection with the Tribeca Film Festival.

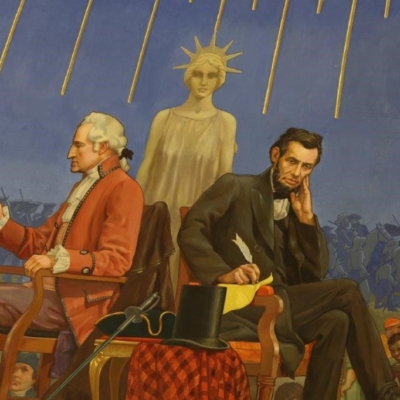

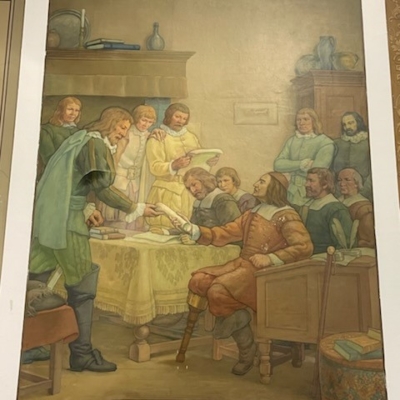

The murals, the principal muralist of which was the Italian-born painter, Attilio Pusterla, are glorious. They consist of painted scenes of persons, events, and objects, as well as painted decorations on the ceilings of corridors and the like. They can be found in the vaults in the entrance area, on the ceiling of the colonnade, in the main circular corridor surrounding the rotunda, in the radiating corridors on the first and second floors, in the ceremonial courtroom (Room 300, recently designated the Paul G. Feinman Ceremonial Courtroom), in the Norman Goodman Jury Assembly Room, and in a conference room on the Seventh Floor. And, most spectacular and celebrated of all is “The History of the Law,” which adorns the ceiling of the court’s rotunda, which is massive: 200 feet in circumference and rising 75 feet to a cupola that is 30 feet high, 20 feet across, with ten stained glass windows and a clerestory. The rotunda ceiling and other murals on the ceilings of the first floor are especially impressive, for their extent, the obvious quality of the painting, and the brightness of the colors.[49]

The ceiling and wall murals in the entrance lobby, rotunda, and radiating corridors on the first and second floors are not true frescos, but are images painted over dried plaster.[50] As a result, the murals are particularly susceptible to water infiltration and damage. By the mid-1980’s, the rotunda and lobby murals had become seriously degraded, including by significant flaking that exposed the white plaster beneath the painting. County Clerk Norman Goodman, the Administrative Judge of the Supreme Court, Civil Branch, New York County, at the time, the Hon. Xavier C. Riccobono, DCAS Commissioners, and leading bar and community figures undertook a campaign to restore the murals and upgrade other parts of the building at the same time. The repairs and improvements that were made were very significant ones, including the installation of a new copper roof for the rotunda intended to stanch the leaks that were damaging the rotunda and lobby murals, installation of air-conditioning court-wide, refurbishing the great chandeliers on the first floor, including those under the portico, and rehabilitation of the steps on the front of the building. To achieve this last, it was necessary to remove and reset all 100 feet of each of the 32 steps leading to the portico so that the structure supporting the steps, which was failing, could be replaced. Lighting was upgraded in the courtrooms and the painted stenciling decorating the first and second floor radiating corridors was conserved and, in some corridors in which the stenciling had regrettably been painted over, repainted entirely. The highly regarded art conservator, Constance Silver, was retained for the conservation of the rotunda and lobby murals. DCAS contracted for the restoration of the artwork in the radiating corridors on the first and second floors. The well-respected construction management firm of O’Brien-Kreitzberg & Associates, Inc. was retained for the upgrade of courthouse facilities. The scale of the project was such that the conservation of the murals and the upgrading of courthouse facilities, which began in the late 1980s, continued deep into the 1990s.

The murals are about 85 years old. Though indisputably beautiful and very well crafted, they are period pieces, subject to the societal limitations of the time of their creation; the images present an idealized, incomplete, and not entirely accurate vision of history, and are not welcoming to all groups in the way we would expect of contemporary art.

One way by which to approach art of the past is by “contextualizing” that art. Artistically valuable paintings and other art objects should not be “edited” or “revised” or “improved;” rather, the art must be conserved and its integrity must be protected. But the viewer’s experience of it and understanding of it can be expanded and enriched by the presentation, in the same location or nearby or in the same facility, of information (which could be merely drawing the attention of the viewer to the historical limitations of the work or could be more than that) or works of contemporary art that can create a broader, more accurate context for the viewer or stimulate the viewer to think about the art in a more complete way. A project along these lines has been underway recently at the Appellate Division, First Department. This effort has been discussed in the press and at a recent program at the court.

Perhaps some might someday suggest a contextualization project for the New York County Courthouse. As no such idea has been formally proposed insofar as we are aware, we do not wish to get into details regarding, or express a view on the advisability of, such a project. But we do note a couple of things. The public areas of the County Courthouse are substantially larger than those at the Appellate Division and there are blank walls in courtrooms that could, if warranted, accommodate art. In the Feinman Ceremonial Courtroom (Room 300), as we have noted, the walls were blank at the time of the opening of the courthouse in 1927. Murals were added later. There is still blank wall space in that room today. (To be more accurate, acoustical tiles were placed on portions of the walls, which were later painted over, thereby rendering their acoustical properties more or less ineffective.). We are of the opinion that it was intended that more murals were to be added to walls in that room than are seen there today. If contextualization through modern art were ever thought to be needed, the ceremonial courtroom of the court would seem to be a reasonable situs for the effort.

Two cautions, though, seem to us to be in order. First, any contemporary art that might be added to the courthouse ought to respect the design and the aesthetic qualities of the building. If such art were to be jarring and to clash with the original design and setting, that outcome might be off-putting to the viewers and perhaps prove counter-productive.

Second, if there are limited resources to be used in the maintenance and updating of the courthouse (and we presume that resources will always be limited), the most pressing use for them must be to protect the courthouse in its current configuration from the ravages of time, dirt, use, adverse circumstances, and the impact of the elements. We need first to be sure, for instance, that the rotunda mural is in good condition and that its paint is not flaking off the plaster due to the infiltration of water before we expend energy and resources in thinking about how to improve its impact on the viewer of the future.

To say that air conditioning was installed building-wide is to employ only a few uncomplicated words, but the actual work was by no means simple. One of the generally-unknown, perhaps unique aspects of the building is that Lowell designed and included an early version of “air conditioning” in the structure. Since modern electrical air conditioning was not considered practical for the courthouse in 1927,[51] all the windows in the courtrooms and offices opened. As we noted, ventilation was one of the concerns the Justices of the court had with Lowell’s circular design. There were also individual fan units installed on the walls of various offices; some of these still exist today. In addition, though, Lowell installed building-wide a system of huge fans embedded in the structure of the building accompanied by ducts to circulate air throughout the courthouse. Those fans could still be turned on in the 1970s/1980s, though they were by then no longer used for the purpose for which they had been created, having been displaced by the arrival of individual air conditioning units in the 1960’s/1970’s. Individual units in Chambers, courtrooms, and various offices brought about a theretofore unknown level of comfort, but the corridors and other spaces lacked them, and so the building in summer could be more or less comfortable in some places and sweltering in many others. It was rumored that, after the Civil Court of the City of New York, New York County, was built at 111 Centre Street, at a time when there were no individual air conditioning units at 60 Centre Street, the Justices at 60 Centre briefly considered abandoning their building for 111 Centre, principally because the latter had central air conditioning and a bathroom in each Chambers. Fortunately, that never came to pass.

Many a homeowner may be familiar with what is required to make “central air” a reality in a home that was not constructed with it nor with the infrastructure for it in place. The principal problem is usually the major one of installing ductwork that does not exist in space not originally designed for it, although this process was assisted at 60 Centre Street by some of the ducting that Lowell had installed for his “air conditioning system.”

The court-wide air conditioning work in the 60 Centre Street courthouse required that all of its courtrooms and Chambers be vacated for a time, and so there was a massive form of musical chairs that played out over a period of years. Furthermore, all of the court’s back offices and all the offices of the County Clerk had to be vacated and moved elsewhere in a courthouse that lacks any spare space to function as that “elsewhere.” The work in the back offices was, of course, much more extensive and complex than moving a Chambers, disruptive as even a Chambers move was, and so the transplantations lasted for months. Obviously, at the end of each transplantation, all of the files, boxes, equipment, etc. from each office had to be moved back to its original location. So, for example, the County Clerk’s vast main office in the basement (Room 141B), which performs many functions and accommodates large numbers of visitors daily, was moved, complete with many files, records, and much necessary equipment, to the ceremonial courtroom, Room 300. When the County Clerk’s main office was finally, after months of residence, able to return to its space on the ground floor, the court’s Administrative Office was then relocated from the Seventh Floor to the ceremonial courtroom and continued operations there, likewise for months. In order just to accomplish the air conditioning portion of the renovation project, it was necessary to move every workspace in the entire courthouse for a period, in some instances for an extended period, during which time the court, the court’s back offices, and the offices of the County Clerk nevertheless had to continue to carry out all of their essential functions, which is what they did. The ability of the court and the County Clerk to carry on their labors throughout this project is a testament to the patience, dedication, fortitude, and hard work of the Justices, attorneys, staff, and County Clerk personnel who labored in the courthouse in those years.

The renovations at 60 Centre Street in the late 1980s and 1990s were on such a large scale, and the complexities that they entailed were so extensive, that, in an ideal world, the building would have been vacated entirely throughout all of this construction work. When more than a decade ago a major renovation was undertaken of the Thurgood Marshall United States Courthouse at 40 Centre Street, that courthouse was indeed vacated entirely during that work. “How the other [Federal] half lives!”

The air conditioning portion of the renovation project at 60 Centre brought a theretofore unknown level of modern-age comfort to the courthouse (or, to be more accurate, to most of it since there are still public restrooms and some other spaces to which the relief did not extend). To achieve this, however, it was necessary to install air conditioning machine rooms. These were placed on the roof of 60 Centre, as well as in the portico and in the sub-basement and intruded significantly into what had been large open spaces in the last two of these locations.

The massive renovation effort achieved conservation and enhanced protection of the murals in the rotunda and lobby. Today, the colors of the murals on the rotunda ceiling and elsewhere on the first floor, for example, remain vibrant and bright, belying their age of more than 80 years. The passage of the years had been kinder to other major wall murals in 60 Centre Street than to those in the rotunda and the lobby and the other murals were not included in the building’s art conservation project of the late 1980s to early 1990s. Those other wall murals are to be found in the court’s ceremonial courtroom, Room 300, in the Norman Goodman Jury Assembly Room, Room 452, and on the Seventh Floor. An earlier mural conservation effort had been undertaken successfully in the Jury Assembly Room, particularly on the west side of that room in which smoking had once been permitted (hard as it is today to imagine such a thing), which had caused significant discoloration of murals depicting important New York City buildings and settings of the 1930s. The fixtures in the Jury Assembly Room, which had been hung from long “stringers,” were raised to the ceiling to provide unobstructed viewing of the Jury Assembly Room murals.

The immediately preceding paragraph needs to be qualified in one regard: more than a decade ago, one of the murals at the easterly end of the Jury Assembly Room was stained by water leaking from a lavatory above and that staining has yet to be addressed.

The renovations were vital and improved conditions in the courthouse, but they took place some 30 years ago, and with a building that is now almost 100 years old, there is always more work to be done, especially if conservation efforts past are not to be undone by the sheer passage of time, accidents, and the workings of the elements that can see their way to getting inside. And, as we discuss further later, experience has shown that the maintenance of the courthouse needs to be upgraded. Indeed, water infiltration is once again damaging some portions of the rotunda mural. Given the very extensive construction work done in the courthouse during the renovation project, it would have made sense to have included the courthouse’s aging heating and plumbing systems in the project. The court at the time proposed that this work be done. For whatever reason, that did not happen, which only means that all these many years later, that work is in even greater need of being done, with what will be very significant disruption of court operations.

There are many other degraded conditions in the courthouse that require attention and repair. For example, busy and crowded clerks’ offices have over time become worn. Some offices occupied by attorneys are too crowded as well and have a threadbare appearance, to such an extent as no doubt shocks some attorneys new to the staff who come from the private sector. Various ceilings are marked by water damage. Marble has become broken in various places and falls from the walls. There are missing marble door frames that have been replaced with pine boards, some painted, some not. In other places marble is missing or in need of repair. The clocks original to the courthouse, which are prominently displayed in the courtrooms over the judge’s bench, in some instances have ceased to work, some have lost their arms, etc. At this point, the public restrooms are, at best, mostly rather dingy. Their original pedestal sinks and expansive marble installations are well worth preserving, but significant refurbishing of those important accommodations is now very much in order.

Some of the shortcomings that have marked the court’s condition in recent decades and that persist today are the result of neglect and sometimes of mistakes, or even a combination of both. In April 2008, a vehicle traveling north on Centre Street, which must have been proceeding far too fast, jumped the curb, injured six pedestrians, and took out 25 feet or so of the railings at the foot of the portico stairs. The railings, which were made of bronze, were not a feature of the courthouse at its opening, but were in place by 1954, if not earlier. The damaged portions of the railings were “repaired” by the City: iron pipes were inserted in the place of the lost bronze rails and these were connected to the surviving portions of the bronze and wrapped around with duct tape. More than 14 years after the accident, the, let us say, not-very-elegant and purportedly temporary substitutes for the bronze are still in place, including such parts of the duct tape as have withstood the ravages of the weather or been renewed.

At some point along the way, the City felt the need to re-anchor the railings, which was done through the use of iron anchor bolts. Iron expands as it rusts and therefore should never be anchored in granite or similar stone. The iron bolts rusted, then expanded, and thereby fractured and damaged a great many of the granite steps beneath the railings in question, causing portions of granite to splinter off.

The writers of this piece ascertained after consultation with an expert in stone that the broken steps could be repaired by inlaying new granite where the old has been fractured. We also discussed the problem with the railings with a company specializing in bronze fabrications and learned that the entity could repair the railings. We regret to say that the work has never been commissioned.

Thus, the very entrance to the courthouse, where the visitor ascends the majestic staircase, has been compromised by neglect and error, which have not been corrected despite the passage of years. The stewards of this important courthouse are the same stewards who are responsible for maintaining, for example, City Hall and the Tweed, and we doubt that such conditions as are here described would go unattended for so long at either one of those buildings.

Another problem with the staircase has been remedied, after a fashion. Some years ago, the awe-inspiring staircase became a very-well-known destination for floods of skateboarders after hours and on weekends. Their presence on the stairs was completely inappropriate, as well as very dangerous to them. Further, the oil used to lubricate the wheels of their boards caused significant staining of portions of the portico stairs. The “solution” arrived at was to place interlinked metal crowd-control fencing at the foot of the steps across the whole width of the portico staircase. This action thwarted and displaced the skateboarders, but, unfortunately, this solution to one problem caused another, defacing Guy Lowell’s beautiful staircase and façade with all of these many unsightly fences. The skateboarders, meanwhile, are still around, having moved across the street, where they continue to place their lives, their limbs, and the integrity of their skulls at risk by using the fountain in Foley Square for a skateboarding rink.

Over the decades after its opening, the courthouse suffered some very regrettable losses of original fixtures. Some of these losses occurred as the result of foolish decisions by those in authority and others through negligence or vandalism. For example, in photographs taken at the time of the opening of the courthouse that appear in this article, we can see the stately light fixtures, which we understand to have come from Tiffany Studios (see below), that graced the ceiling of the Ceremonial Courtroom (Room 300). We believe that the same fixtures were used in all of the courtrooms of the courthouse. The photos we have of these courtroom fixtures show clearly their resemblance to original ceiling fixtures that have survived elsewhere in the building, those hanging and those affixed directly to, for example, hallway ceilings. At some point, the courtroom ceiling fixtures were replaced. We are not certain when this occurred, but we do know that it happened before 1970, perhaps in the 1940’s or 1950’s. The original lights disappeared, making way for the uninspiring successors that can be seen today. What happened to the discarded original lights is unknown to us.

We are not certain why this change was made. We suspect, however, that it was done in a bid to increase the amount of light in the courtrooms. We note elsewhere in this article that the courtrooms receive light from large windows facing on the exterior and from the large internal light courts, but the ceilings of the courtrooms are certainly very lofty so that lighting is a challenge. Nevertheless, there surely must have been better options available to the custodians of the courthouse in the 1940’s/1950’s than removing the Tiffany fixtures. Today, those fixtures, which we can see, both from the photos and from their surviving cousins, were very beautiful, would be regarded as, if not priceless, at least highly valuable. If any such fixture had survived and made its way into private hands, it could easily today inspire a segment of Antiques Roadshow. More important than the monetary value lost when these original light fixtures were removed, though, is the loss of their special beauty and the damage their removal did to Guy Lowell’s artistic vision for the interior of the building. Surely the courtrooms, the function of which is at the heart of the reason for the very existence of the courthouse, were among the spaces in the building that most deserved to be the subject of intensive and devoted care by the authorities.

A very sad irony is that, during the restoration work in the late 1980’s/1990’s, attention was again given to improving the lighting in the courtrooms, the replacement fixtures having proven insufficient for the task, which is to say that the original, beautiful fixtures were discarded on the basis of a justification that proved inadequate. More powerful bulbs were placed in the fixtures. Fixtures of the “high hat” variety were added at that time as well.

At its opening, the courthouse also benefitted from the presence of many attractive task lamps or desk lamps, which may have been Tiffany creations. Many of these disappeared over the years, although a few could still be found in 1970. In the years that followed they became entirely extinct, probably due to theft.

This account of loss provides suitable context for another depressing story – – actually a downright scandal – – which is that of the City’s “Save a Watt” program of the 1970’s. An account of this misadventure by Adrian I. Untermyer, Esq. is one of the 20 stories being posted by the Historical Society of the New York Courts in celebration of the Society’s 20th anniversary.

The “Save a Watt” program was well-intended, seeking to save energy, but we know, or should know, all about the road that can lead from good intentions that are unaccompanied by careful thinking, and such thinking was conspicuously lacking in this instance. Under this program, the City planned to replace the vast preponderance of the light fixtures in the courthouse, which were incandescent, with more modern, fluorescent ones that could, the City believed, provide light at lower cost.

One day, an attorney on staff at 60 Centre chanced to notice in the hallway near his office that some of the pendent light fixtures had been taken down and were lying on the floor in what seemed a precarious, potentially ominous state. The attorney’s reaction to what he saw was fear that the electricians intended to discard the fixtures and replace them with new ones. An electrician advised that the work that was in progress was indeed a part of a plan to modernize the lighting fixtures in the courthouse.

This attorney was not part of the administration of 60 Centre and thus had no knowledge of maintenance procedures in the courthouse nor any responsibility for the subject. Fearing what was going to ensue, however, which seemed to him a travesty, and being unsure whether the administration of the court was aware of the situation, the attorney brought his observations to the attention of the administration. It turned out that the administration was entirely in the dark about the project. Although the building is a courthouse, the leadership of the court will not normally be aware of all maintenance tasks being undertaken in the building on a day-to-day basis since, as we noted earlier, the courthouse is owned by the City and maintained by it. As this project, however, was one of considerable scale and its consequences were significant, one would have imagined, and normal and orderly administration of a project of this sort would have required, that the City would inform the administration of what was being done, but it never bothered to contact the Administrative Judge.

Upon learning by this accident what was underway, the Honorable Edward R. Dudley, who was the Administrative Judge at the time, and County Clerk Norman Goodman contacted the City about this project. The Landmarks Preservation Commission was informed by the attorney of what was happening, and, to its credit, promptly sent someone to the courthouse to investigate. Judge Dudley and Mr. Goodman were very unhappy, not only about not having been informed, but, more important, about the nature of the project the City was intending to pursue. The City was intending to replace almost all of the incandescent fixtures in the courthouse with fluorescent ones, meaning that the great majority of the original light fixtures were to be removed permanently from the courthouse.

These fixtures consisted of pendent fixtures, two and one-half to three feet long, in which globes constructed of brass and glass were hung from the ceilings on bronze pendants; other such globes, call them “ceiling globes,” which were anchored directly to the ceilings by brass work without pendants; and numerous heavy (about five pounds each), decorative bronze ceiling pieces with bulbs, which were informally referred to as “sconces” and which were especially prominent in connecting corridors. All of these fixtures were original to the building. The City’s plan was to replace the original fixtures with plastic and tin “fixtures,” which looked as though they had been purchased for $ 3.99 each at Woolworths. The original fixtures were beautiful and of great quality. The original globe fixtures were very elegant and the bronze sconces were very decorative and distinctive. According to the Landmarks Preservation Commission, all of the original light fixtures were the work of Tiffany Studios.[52]

The City had no plan to save the fixtures for possible use in the courthouse at a future time nor to use the fixtures somewhere else, although any such intention would have been no excuse for removing them from the building for which they had been designed in 1927. The intention, rather, was to put the fixtures up for sale, at an auction or otherwise.

Moreover, it was evident that, despite the City’s avowed interest in preserving landmark buildings, no consideration, or at least insufficient consideration, had been given to whether the benefits that would purportedly flow from the application of “Save a Watt” to Guy Lowell’s courthouse would be outweighed by the destruction the City intended to effectuate. The “Save a Watt” program, whatever may have been its merits in buildings of lesser historical importance than 60 Centre Street, was conspicuously short-sighted, foolish, and harmful there, indeed an act of despoliation and disrespect for the architectural integrity of this important courthouse during which the building suffered losses from which it has not recovered.

The negotiations of Judge Dudley and Mr. Goodman eventually led the City to agree to a compromise of a sort, but not to a complete end to the program at 60 Centre. That the program did not proceed as originally intended was good news, up to a point. All of the pendent globes then in existence were preserved. Repairs were made to glass in some of the pendent fixtures and the ceiling globes. The remaining ceiling globes were to be collected for preservation to the extent possible and repositioned elsewhere in the courthouse, on the sixth floor and to some extent elsewhere. In all of the confusion of the time, however, some of the ceiling globes went on walk-about, that is, went missing, which added to the large losses of them that had taken place over the decades prior to the “Save a Watt” program, some of which losses no doubt came about by way of pilferage.

The bronze ceiling sconces were at the time of the negotiations with the City still in place as originally installed. The City insisted that all but a couple of the sconces be taken down and replaced with the cheap plastic and tin fluorescent “fixtures.“ That is what occurred, except for the couple that were given a reprieve and survive to this day. The authors estimate that more than 200 of the bronze sconces were taken down and carried away, to a sale or perhaps elsewhere. (The authors fear that the planned sale may have been in practice somewhat porous and that various fixtures might have made their way to places that the City did not actually wish them to reach.). The sconces were replaced with the poor-quality plastic and tin “fixtures.”

All of these plastic and tin “fixtures” are still in place in the hallways and offices of the courthouse today. Of course, they look even worse today than they did in the 1970s. Many of the covers on these “fixtures” are broken or missing and many of the fixtures do not work. It should come as no surprise that such cheap “fixtures” tend to malfunction and, once broken, tend to stay that way, even for years.

Had Judge Dudley and Mr. Goodman not intervened, things would have been much worse than they turned out to be. But the compromise they were able to engineer was not sufficient to head off the program in substantial part, despite their wish to do so. Since the building is owned and maintained by the City, Judge Dudley did not have the authority to prevent the program from proceeding. He did not have the formal power to protect even a single fixture. The Landmarks Preservation Commission that the court brought into the discussions energetically lent moral support to Judge Dudley’s arguments, but the Commission could not do more than that as it lacked authority or jurisdiction over the matter. So, the program proceeded with the modifications described. From the perspective of preservation of the architectural patrimony of the city, the “Save a Watt” program as finally implemented had little to do with “savings” at 60 Centre Street and was a disaster for the courthouse. The program was all the more regrettable when one thinks that had the City waited for a while, advances in illumination in the form of screw-in LED bulbs, which are ubiquitous today, would have made the entire undertaking completely unnecessary.

Architectural and decorative details were obviously of great importance to Guy Lowell and we destroy such details at serious peril to our artistic and cultural heritage. But regret about such devastation is not a sufficient reaction. Rather, in the view of the authors, the City should take prompt action to repair the enduring consequences of its municipal malpractice. The City ought to consign all of the plastic and tin “fixtures” to the scrap pile and contract with Excalibur Bronze or similar foundry to fabricate copies of every one of the ceiling sconces that disappeared, and these should then be installed in place of all of the plastic and tin monstrosities. Excalibur is expert at making bronze copies, which will be exact reproductions of a surviving original.[53] Another entity should be commissioned to make globes to replace all that have been lost. Similarly, the City should, even at this very late date, correct the horrible blunder that led to the removal of the original courtroom ceiling lights by commissioning installation of replacements fabricated to match the originals as much as is possible. We know that this can be done because in 2010, Administrative Judge Joan B. Carey directed that new lighting be installed in place of the replacement fixtures in Room 300 and these new lights were a considerable improvement, recalling the long-lost Tiffany originals.[54] This is the least that can be done to keep faith with Guy Lowell and his vision, which the City had undertaken to safeguard decades ago.

In the 1990’s, a decision was made to replace many of the courthouse’s original doors that were installed in various hallways to provide fire safety. The relevant authorities were of the opinion that more up-to-date fire safety doors were advisable. Representatives of the courthouse argued that it was not wise to remove original court fixtures from a landmark building, but that view did not prevail and the plans were executed. Many original doors, perhaps as many as 150 or more, including double doors, were removed. These doors had panes of wire mesh safety glass, brass fittings, including brass kick plates, and faux wood graining. The doors were sold, discarded, or otherwise handled and they were replaced by the purportedly improved doors. These latter doors were metal and were ugly and pedestrian with a quite discordant appearance, in contrast with the harmonious look of the originals. Perhaps it is a tenet of fire safety procedure that fire doors should have a jarring and unsightly appearance so that the staff and the public will have their attention called to the existence of those doors. If that was the objective, it has been achieved. We wonder, however, whether the modern doors provided and provide such a greater level of safety compared to the doors of 1927 to justify the disruption and the removal of the originals. We have our doubts on that score.

Once the new doors were installed, it was found by the staff that they would lock or close too securely such that they would not operate as normal doors when a fire was not in progress. The staff therefore took to propping the doors open, perhaps not ideal from a safety perspective, something they never did with the original doors. The door handles also have had a propensity to fall off.

We derive from this and other incidents a principle of artistic appreciation and historic and cultural preservation: one should never remove original fixtures from a landmark or otherwise worthy building and replace them with modern fixtures that purport to be improvements over the originals unless there is a compelling reason to do so, not just a reason, but one that has special force behind it. If this principle is not followed, our artistic patrimony will be denuded and degraded as time goes by, even with the best of intentions, as there seems to be an unfortunate tendency in some quarters to regard the architectural work of the past as inferior to what the modern age can produce, when the situation is rather the reverse.

Very recently, the court was obliged to close the back entrance to the courthouse, which is heavily used. The rear door consists of two parts, a regular set of modern glass doors and, on the outside of those, a pair of wrought-iron doors and a surround of the same material. The wrought-iron doors and surround are elaborately designed, with extensive filigree-like work, and are original to the courthouse and thus almost 100 years old. There are problems with the hinges on these exterior doors and there is a danger that the doors may fall off, possibly injuring someone and causing damage to the surround; the doors and surround could even collapse. Because the rear doors have been so heavily used over the years, the closure is a significant inconvenience for the court and those who come to it. The inconvenience will be felt not just by judges, court personnel, attorneys, jurors, and the public generally, but especially by those delivering supplies to the court or removing materials therefrom given the existence of ramps in the area of the doors that facilitate the entrance and exit of those persons. Disabled persons also use these ramps and the rear doors, although the ramps are not ADA-compliant. (ADA-compliant ramps and a lift were proposed in the past, but these remain aspirations only.)

We understand that DCAS estimates that it will take about 18 months to make the repairs required to restore the doors to use and proper function, although it is possible that the rear entrance will not remain closed throughout this entire time. Considering some other examples discussed here, the authors are skeptical about the accuracy of this estimate and, indeed, are convinced that the time required for the repairs will prove to be substantially longer.

In any event, the plight of the doors is a metaphor for the challenges the courthouse faces generally.

Over the course of many years, slightly broken or damaged, but restorable chairs, tables, and benches that were original to the courthouse were simply tossed away. About three decades ago, the court administration put in place procedures to prevent such destruction from taking place and court staff do their best to send original furnishings out for repair, using the court’s equipment budget to fund the cost. When a piece of furniture or the like cannot be repaired, the court tries to salvage portions of it to assist with future repairs of other pieces. Many pieces of original furnishings have been saved as a result.

Original furnishings and fixtures remain at risk, however, or at least it is wise to assume as much. During the writing of this article, one of the authors discovered an original courthouse chair in a location in the courthouse where such chair should most certainly not have been and was able to bring its existence to the attention of administrative staff so that the chair can be returned to a proper location and saved for the future. The same writer also found in a hallway another original chair, this one broken beyond repair, but which could still provide material that might be used to make repairs of other chairs in future. And, not so long ago, it was recommended that all the jury boxes original to the courthouse’s courtrooms should be replaced because it is considered that they are not ADA-compliant. If one wishes to address the courthouse’s remaining ADA issues, the jury boxes is a very peculiar place to start. (As we note later, the jury deliberating rooms themselves represent a notable problem.). Beyond that, if action needs to be taken, the action should be one of accommodation and modification, not destruction. As with the “Save a Watt” program and the removal of the original courtroom ceiling light fixtures, destroying Guy Lowell’s original jury boxes would reflect a failure to appreciate the beauty and quality of the originals and would be wholly antithetical to the landmark status of portions of the building.

We conclude this brief litany of sorrows with this unforgettable episode. In the 1990s or so, a maintenance person, whose duty it was, of course, to preserve and maintain the features of the courthouse, stole original brass door push plates and brass foot plates off of courtroom and hallway doors. It is fundamental that the original fixtures in a landmark building must be preserved, for if such original pieces are lost or destroyed, they cannot easily be replaced, not, that is, by anything of similar quality.

When the authors first came to the New York County Courthouse, digital technology was unknown and rotary phones were in use, although parchment paper and quill pens had left the scene. Things changed, of course, very greatly. The advent of word processing equipment significantly altered the drafting of opinions, with, as but one consequence over time, the gradual disappearance of many stenographers, who were replaced by law clerks or court attorneys expert in the use of the technology. At one point, online legal research made its appearance in the form of a computer accessible to attorneys and Justices in the library. But that expanded, of course, until each Justice and attorney was provided with access to a digital device and could do legal research on his or her own device and, in time, do it at home at night or on the weekends. Many other advances took place as well.